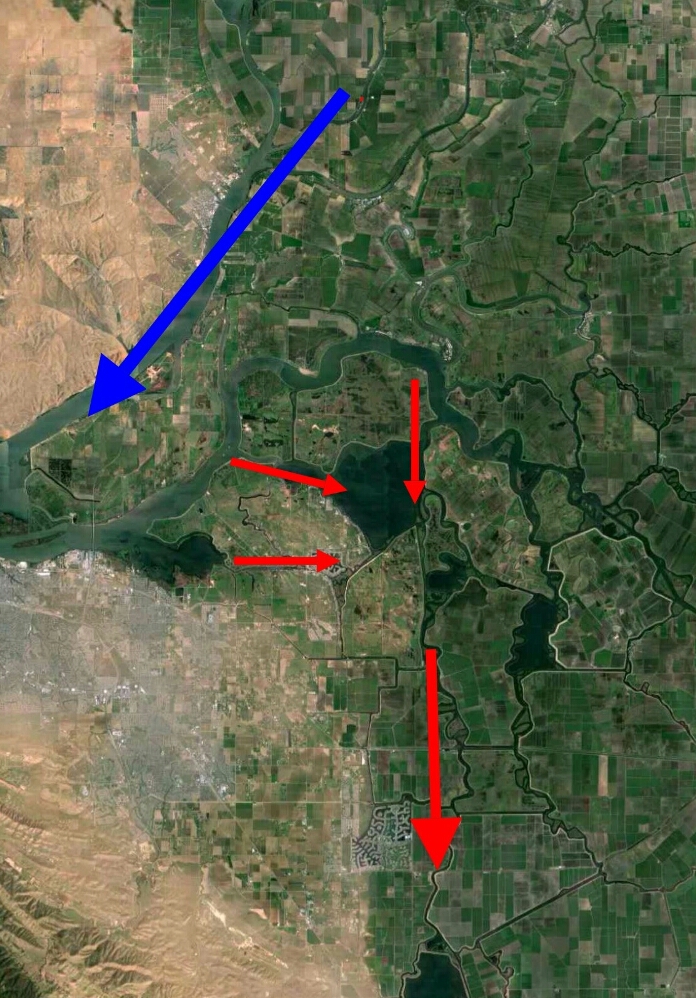

A December 23, 2015 article in the Sacramento Bee1 describes salmon rescues occurring in the northern Yolo Bypass near the outlet of the Knights Landing Ridge Cut. The online SacBee article provides a video of the trapping and hauling process. I posted earlier about the stranding of salmon in the Bypass.2

It is encouraging that the California Department of Fish and Wildlife is addressing the immediate situation and that this effort is getting coverage in the press. However, the SacBee article contains several misconceptions about the problem:

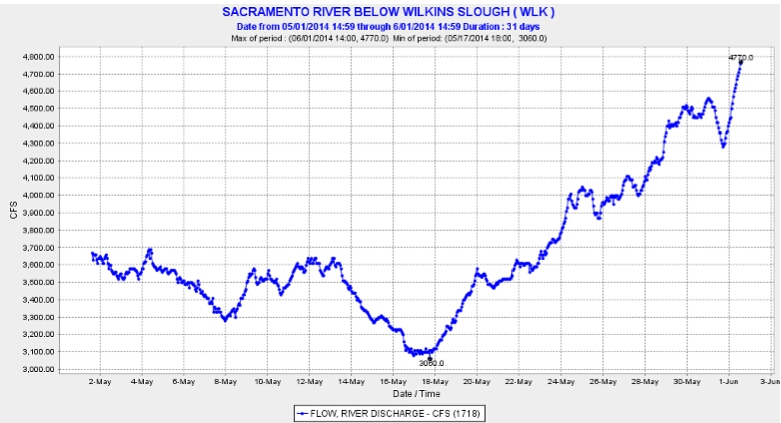

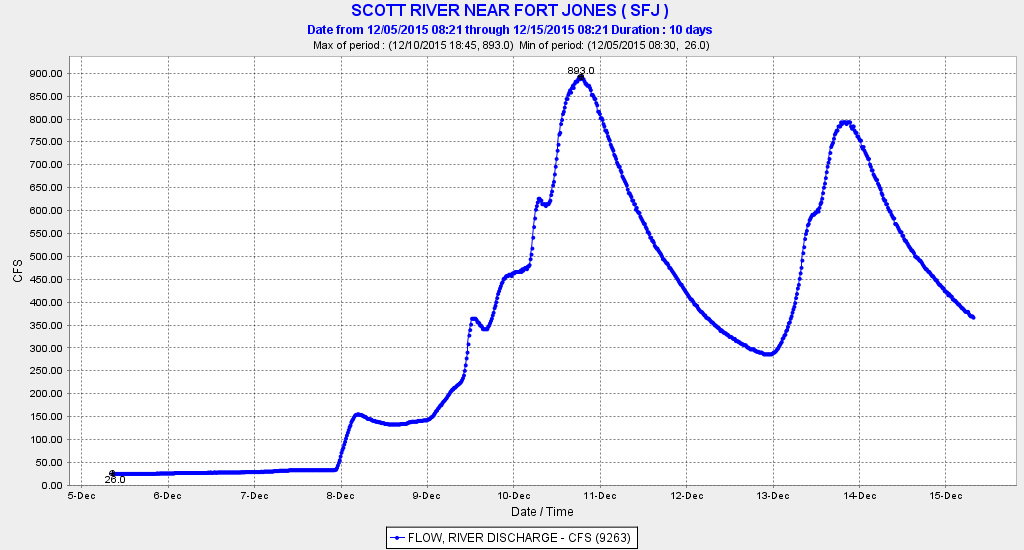

- “Salmon are having problems with the drought identifying which route to go right now.” This problem is by no means unique to the drought. This stranding problem is far worse in wetter years when higher flows into the Yolo Bypass and Colusa Basin Drain attract far more salmon (and steelhead and sturgeon).

- “Beginning in 2013…” – the problem has been known for many decades.

- “That spring, biologists discovered that some 600 endangered winter-run salmon had gotten trapped 70 miles off course in the Colusa Basin Drain system” – the estimate was very rough, given that the agencies acknowledged the problem late in spring and surveyed only a few areas of the Colusa Basin. In addition, they were unable to count all the fish concentrations and to identify the genetics of all the fish.

- “Although conservationists captured and returned many of the fish to the river” – though the effort was commendable, many of the stray fish were not captured and returned.

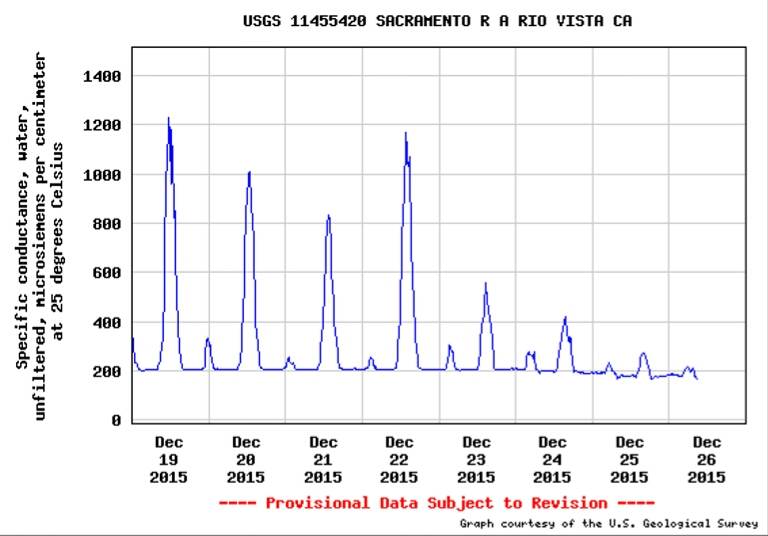

- “Since then, we’ve started building seasonally these traps that we can put in the channel to allow us to move them pretty efficiently” – when flows got high last winter in the Colusa Basin Drain, the trap was removed because it was ineffective. Many salmon passed the trap location (to die upstream in the Colusa Basin), and hundreds were stranded nearby and died (see photo below).

- “The traps are a temporary solution, but efforts are underway to permanently stop the fish from going off-course.” – The traps are better described as a Band-Aid than a solution. They do not work at higher flows when fish passage is greatest. Permanent solutions were prescribed in the 2008 National Marine Fisheries Service Biological Opinion for operation of the federal Central Valley Project and the State Water Project. If a permanent solution is in fact completed next summer as the SacBee article suggests, it can’t be soon enough.

Salmon stranded at Knights Landing Ridge Cut Outlet in northern Yolo Bypass after high flows in December 2014.