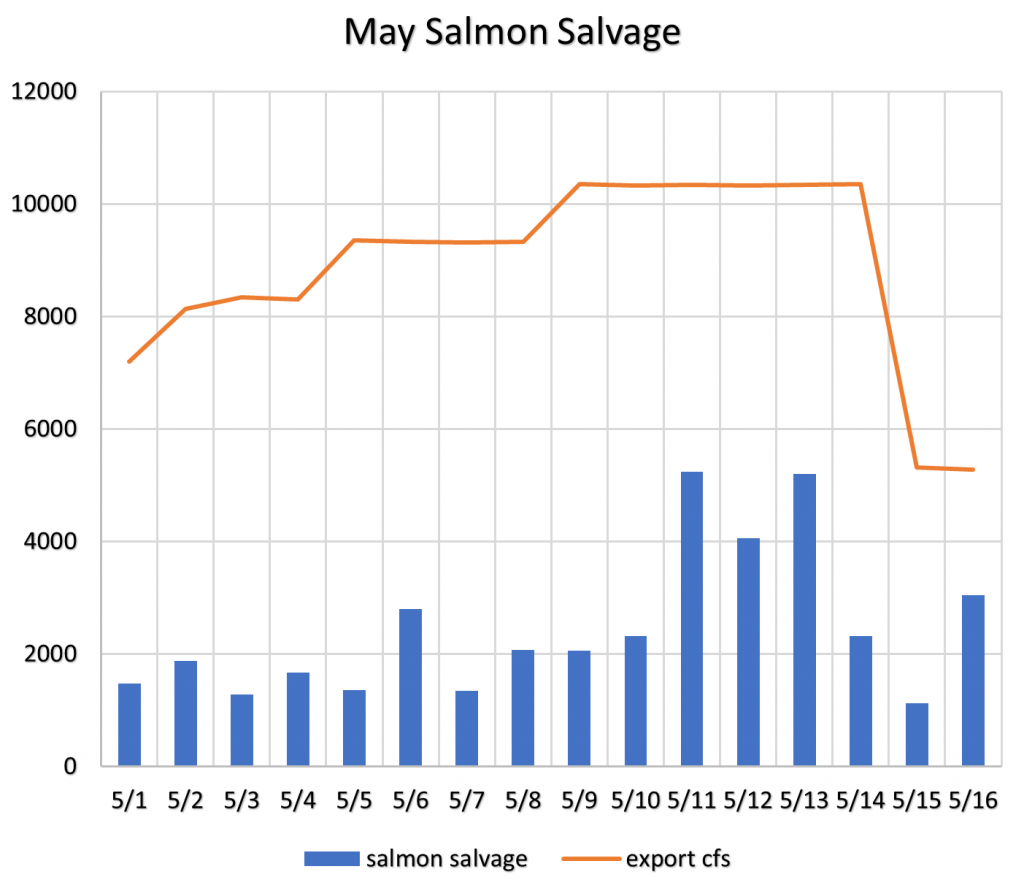

In a March 25, 2018 post, I suggested strong measures to protect salmon populations in the Central Valley. Well, it is time for action number one. Young salmon from last fall’s spawn are pouring down the rivers for the Delta, Bay, and ocean. Hatcheries are about to stock millions of fall-run smolts. Up until last week, young salmon were getting lots of roiling cold water to push them along on their journey. But with a break in the rains snow melt is being trapped in reservoirs, and things are changing. Waters are getting warmer, fish are getting stressed, and predation is up. Sacramento River water levels have dropped over ten feet in the past week, and flow has dropped by half (Figure 1). Water temperatures below Colusa have risen sharply to over 60°F, perfect to stimulate the appetites of striped bass.

Figure 1. River flow at Wilkins Slough on lower Sacramento River, March 26-April 1 2018.

Over the next six warm months, April through September, state water quality standards are supposed to assure salmon of cold 56°F water at Red Bluff and cool 68°F water from there down to the Delta. Outmigrating young salmon need cool water. Newly hatched sturgeon need the cool water in spring. Adult winter-run and spring-run salmon also require the cool water during their spring upstream migration. Adult fall-run salmon need the cool water during their upstream migrationin the late summer and fall.

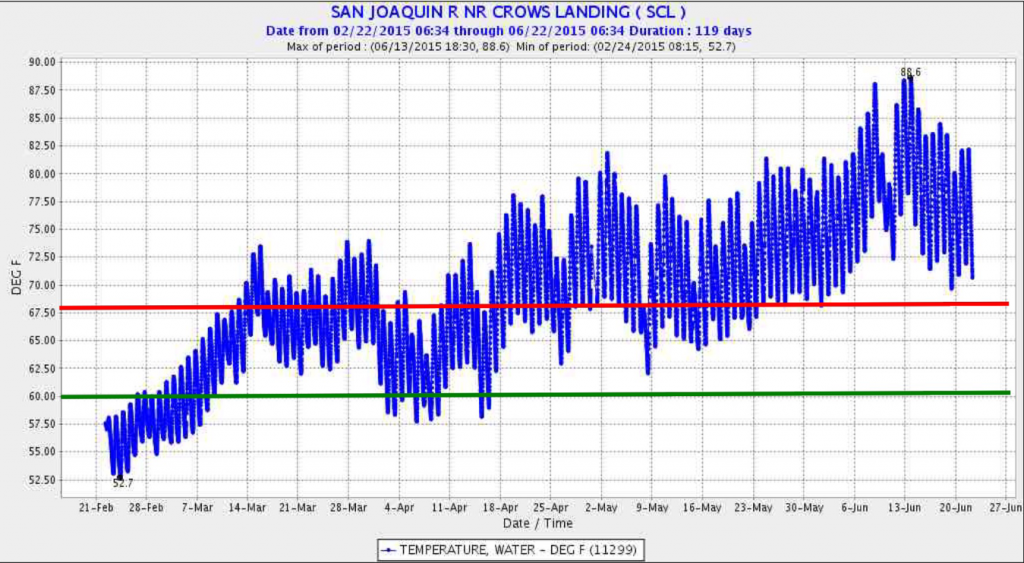

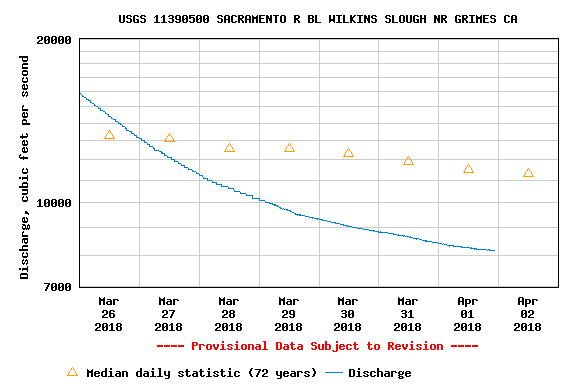

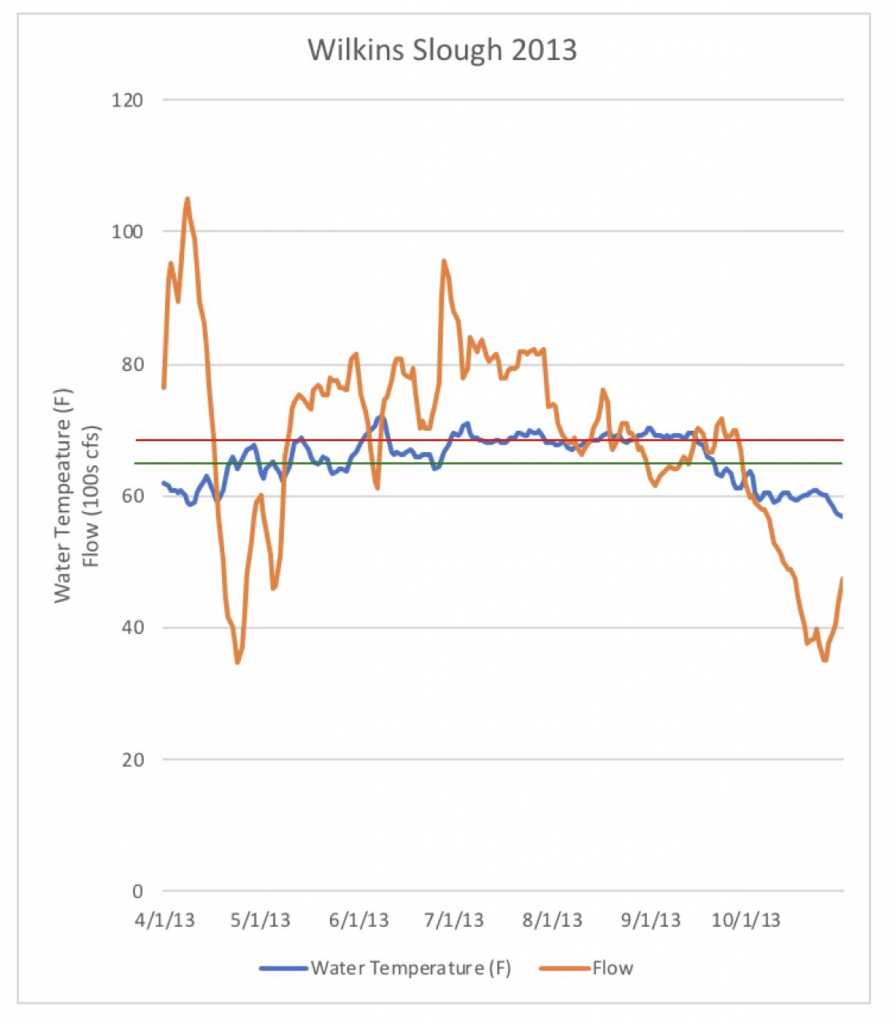

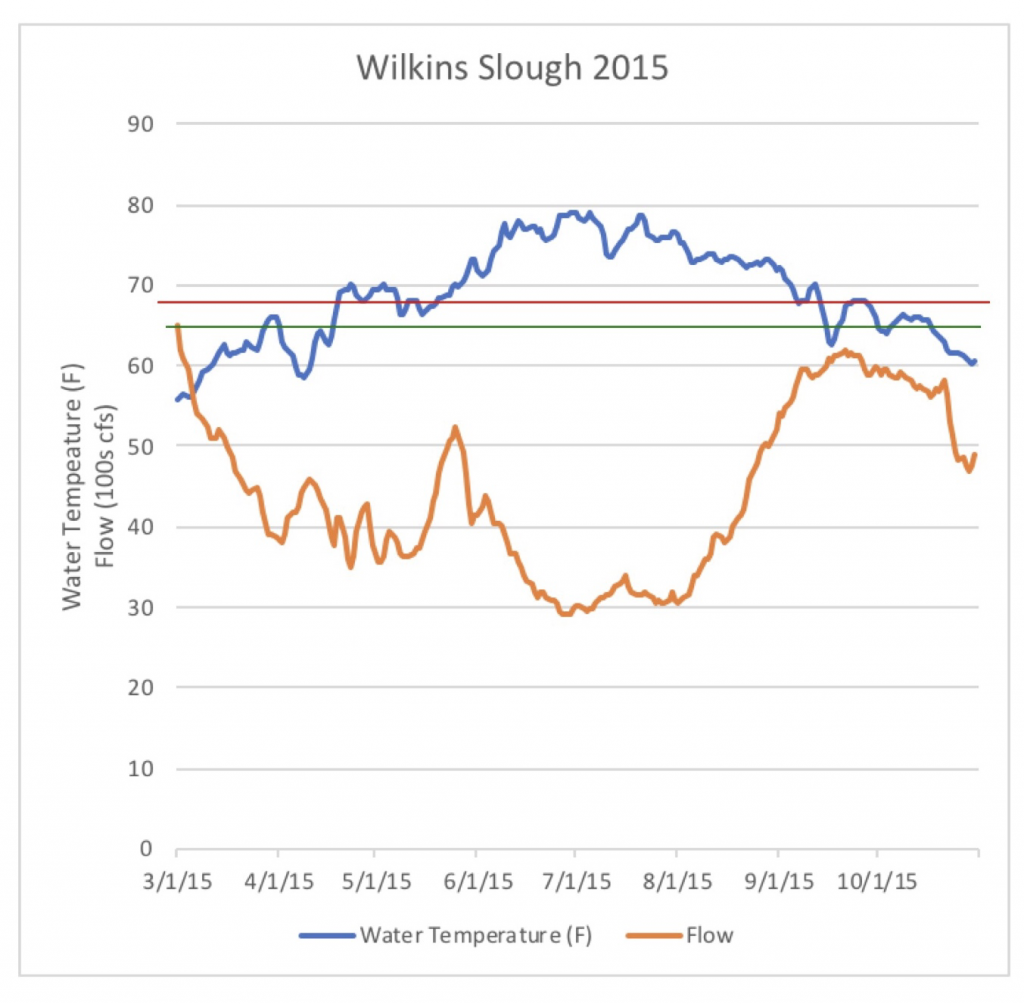

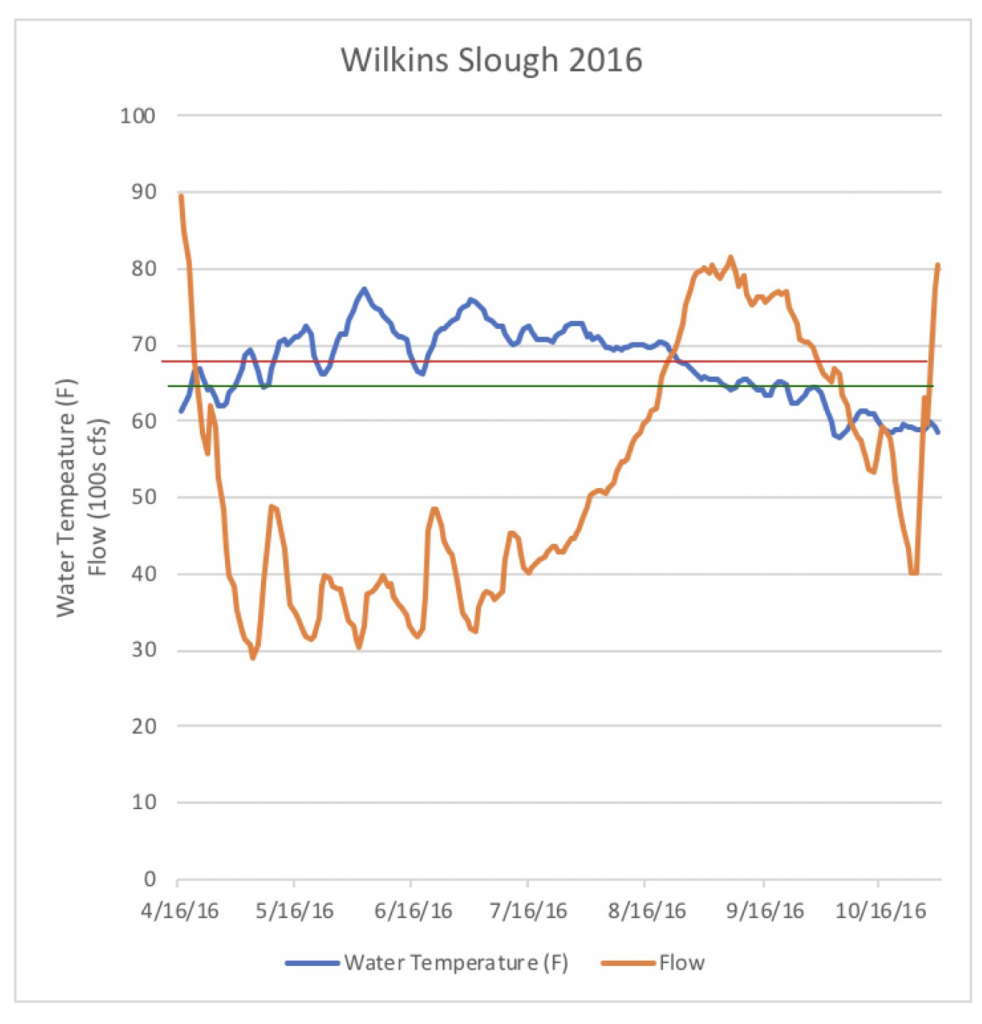

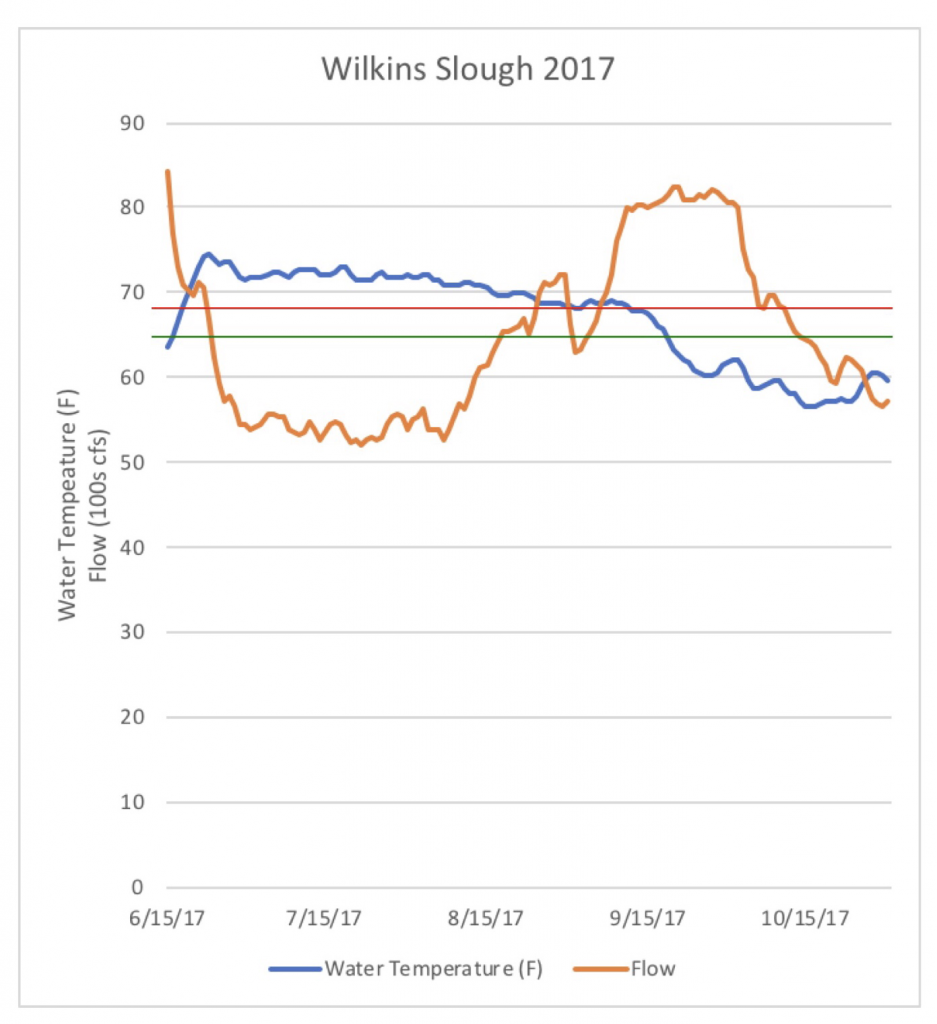

Until a few years ago, the fish were usually provided what they needed, even in a drought year like 2013 (Figure 2). But that changed during the 2013-2015 drought. In 2015, water temperature reached above 68°F by late April and near 80oF in the summer. (Figure 3). In below-normal water year 2016 and wet water year 2017, low Shasta releases and high water temperatures continued (Figures 4 and 5), to the great detriment of salmon and other native fishes like steelhead and sturgeon.

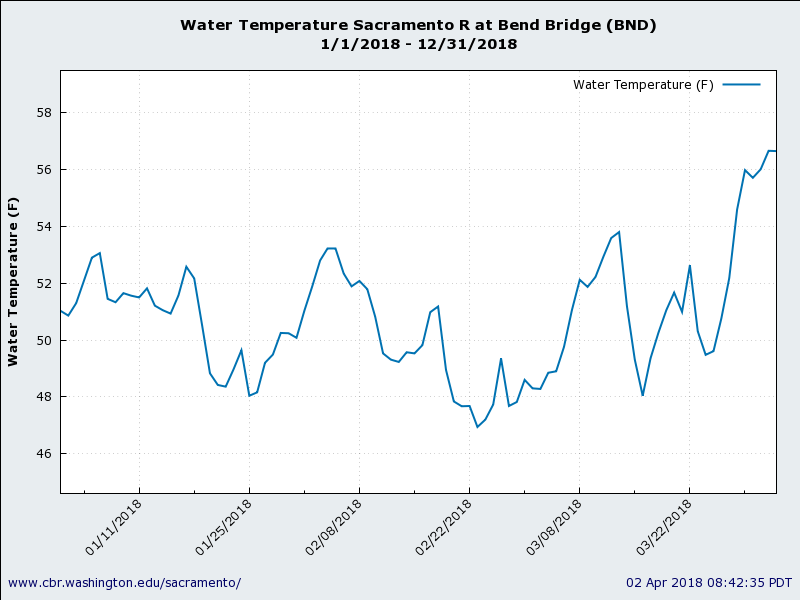

Now, in spring 2018, conditions have already deteriorated quickly. Water temperatures at Red Bluff now exceed 56°F (Figure 6). Soon lower river water temperatures will reach above 65°F.

The answer is simple. At minimum, Reclamation should keep the flow of the lower Sacramento River at Wilkins Slough near 8000 cfs, as in 2013. Shasta Reservoir is 88% full, 105% of average, and the reservoir will likely fill (4.5 million acre-ft) this spring. Federal managers and contractors probably are forecasting a spring flow of 5000-6000 cfs in the Sacramento River at Wilkins Slough, similar to last year. That would save Reclamation 240,000-360,000 acre-feet in Shasta over two months. But the extra storage would come at the expense of water quality and fish standards, and would mean a lot fewer salmon for the future.

Figure 2. Wilkins Slough gage spring-summer flow and water temperature 2013. Green line is 65°F stress limit for salmon. Red line is water quality standard 68°F for lower Sacramento River.

Figure 3. Wilkins Slough gage spring-summer flow and water temperature 2015. Green line is 65°F stress limit for salmon. Red line is water quality standard 68°F for lower Sacramento River.

Figure 4. Wilkins Slough gage spring-summer flow and water temperature 2016. Green line is 65°F stress limit for salmon. Red line is water quality standard 68°F for lower Sacramento River.

Figure 5. Wilkins Slough gage spring-summer flow and water temperature 2017. Green line is 65°F stress limit for salmon. Red line is water quality standard 68°F for lower Sacramento River.

Figure 6. Water temperature at Bend Bridge near Red Bluff in 2018.