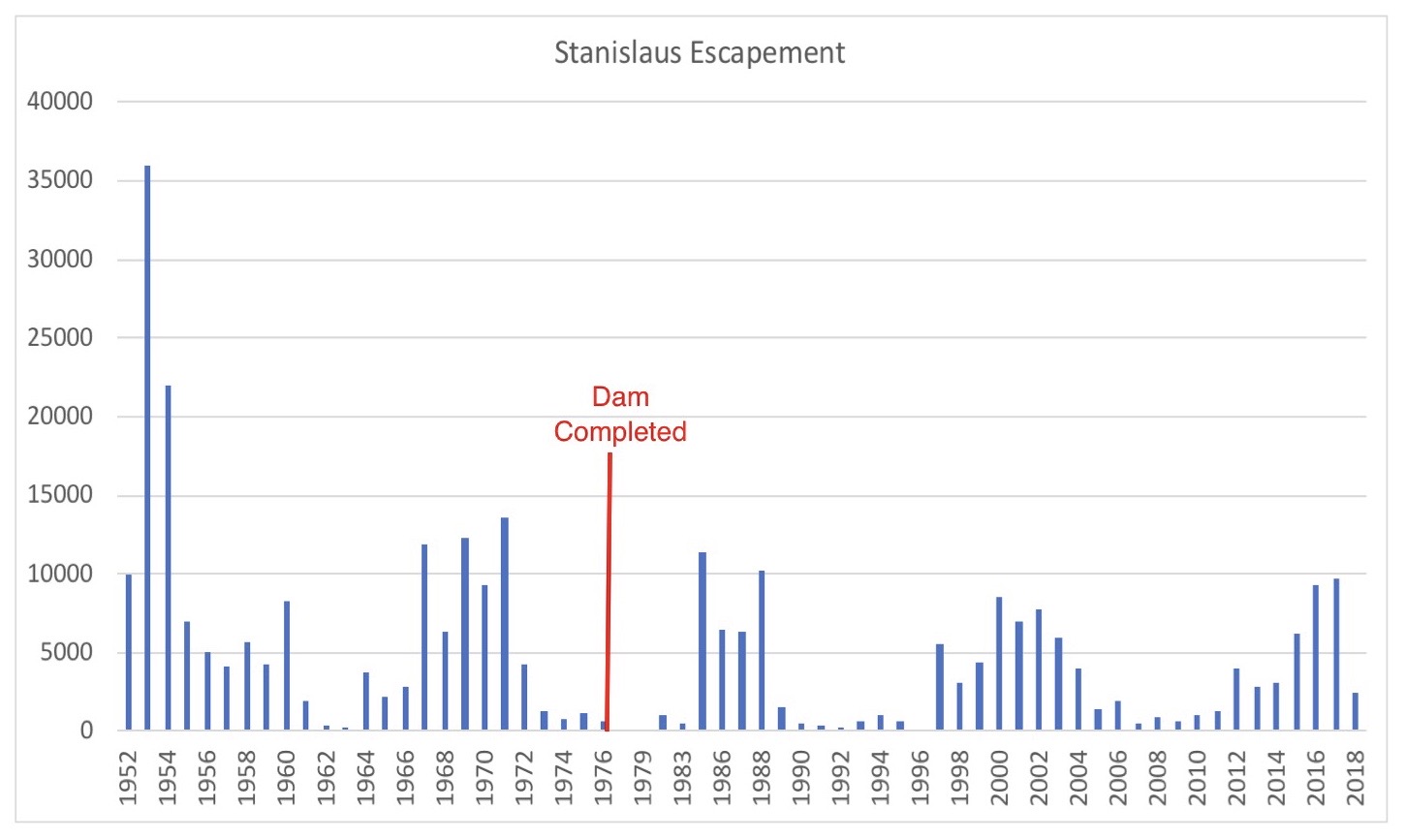

The San Joaquin River watershed has contributed up to a third of the total Central Valley salmon run as recently as 2017, if one counts the Mokelumne River as a San Joaquin River tributary and includes its large hatchery contribution. Though the fall salmon run in the Stanislaus River includes many hatchery strays from throughout the Central Valley, the Stanislaus remains the biggest contributor of wild-produced salmon in the San Joaquin basin (Figure 1).

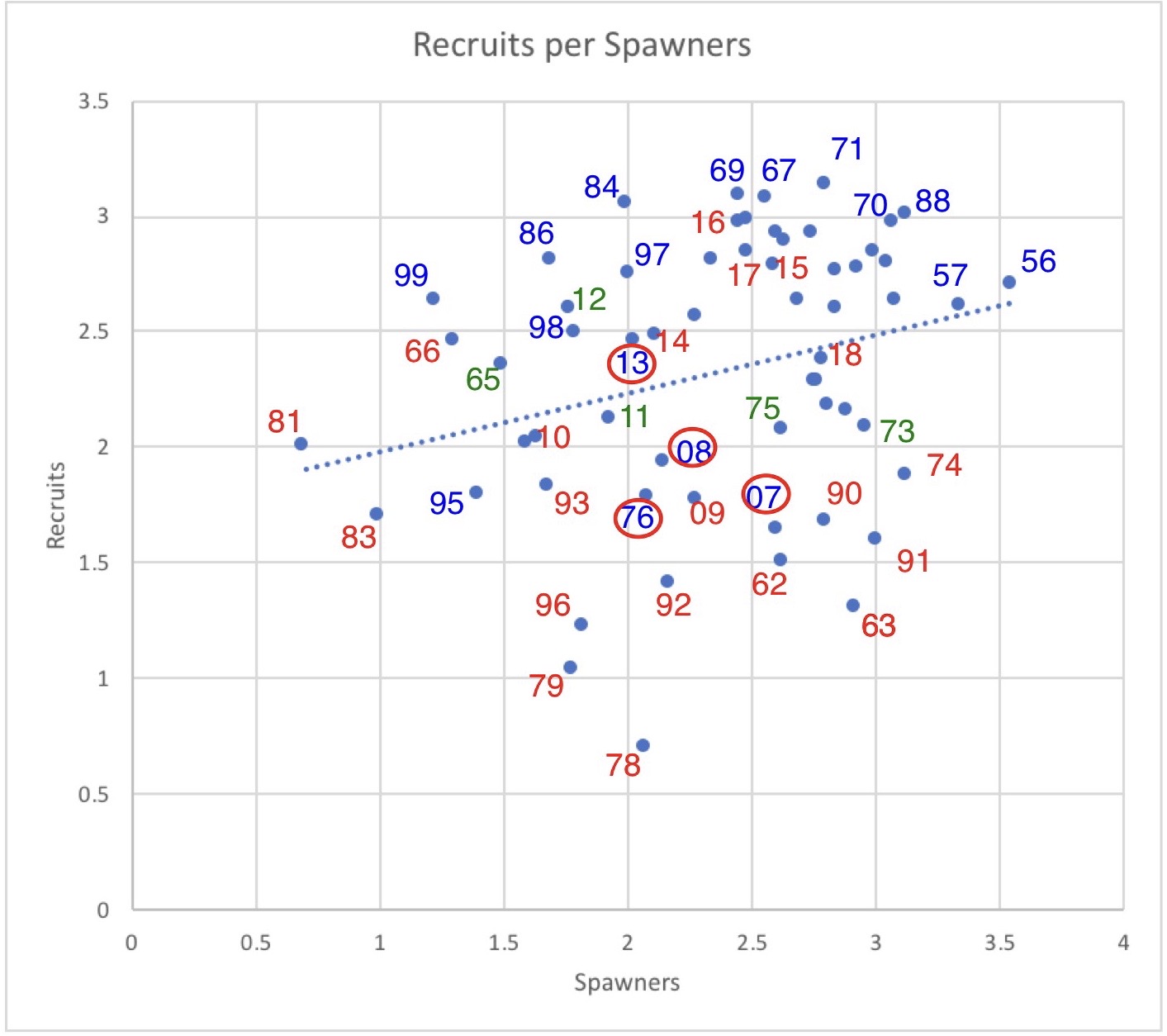

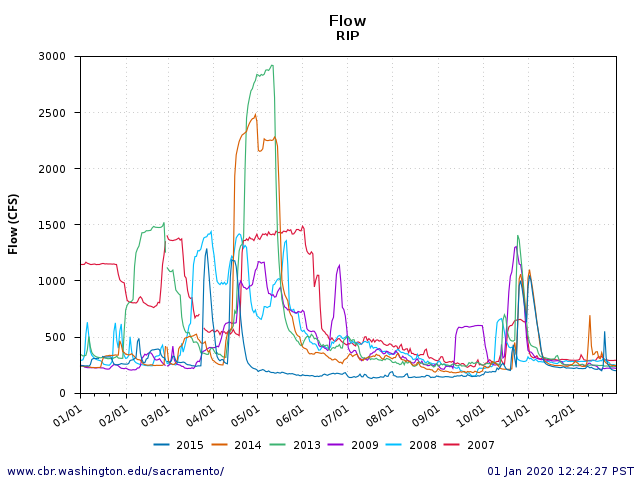

The Stanislaus spawner-recruit relationship (Figure 2) derived from escapement estimates indicates a positive relationship influenced by water-year type. Wetter years (blue) on average provide 10 times the recruitment per spawner as drier years, with normal years providing intermediate recruitment. Severe droughts in the 60’s, 70’s, 80’s, 90’s, and 00’s depressed recruitment and led to declining population trends. Recruitment during 2014-2018 drought-influenced period was much higher than in the prior droughts, thus maintaining a higher recent average population level. In a December 2019 post, I attributed the improvement to increases in hatchery strays as well as to spring and fall pulsed flows from prescribed reservoir releases (Figure 3). The spring flow pulses benefit smolt emigration survival. Fall flow pulses provide attraction flows as well as better spawning conditions (flows and water temperature).

Separating all the factors influencing recruitment is a challenge, but it is critical to prescribing future management. In a recent paper, Sturrock et al. 2019 found that emigrants-per-spawner and recruits-per-spawner through 2014 strongly related to within‐season stream flow variability during the winter-spring juvenile rearing period.

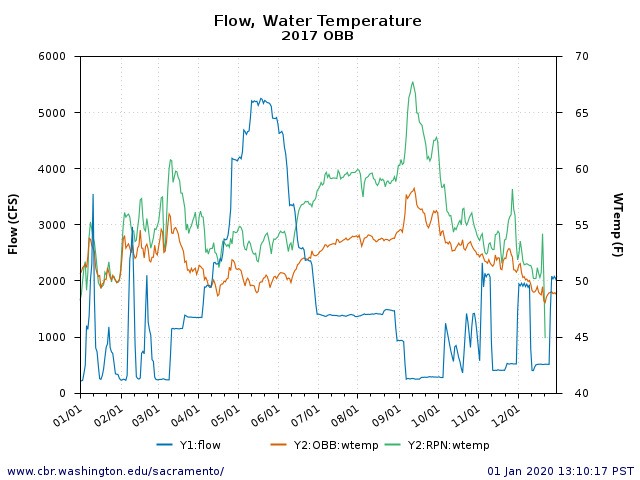

Variability in flow comes from storms, prescribed flow releases, and flood releases.1 Strong runs in drought-influenced 2015 and 2016 were likely higher due to the significant prescribed spring flow pulses in 2013 and 2014 (Figure 3). The strong run in 2017, despite overall poor drought-year 2015 flows (Figure 3), is likely related to the attraction of stray wild and hatchery spawners to late summer and fall prescribed pulsed flows and associated cool waters of the Stanislaus River in 2017 (Figure 4). Most of the 2015 Central Valley hatchery smolt production was trucked to the Bay and subject to high straying rates. The lower San Joaquin and Stanislaus rivers provided good attraction flows and cooler waters in 2017 to accommodate adult Central Valley salmon less inclined to seek their natal streams in routes warmer than the San Joaquin and Stanislaus rivers.

Based on studies of salmon in the Stanislaus, Sturrock et al. (2019) provide recommendations to improve recruitment per spawner and diversity of the life-history portfolio. In recent years, recruitment in the Stanislaus has been overly dependent on the success of parr and smolts emigrating in the early spring. Survival of emigrating fry in winter and older smolts in late spring has been poor. Analyses of otolith cross-sections (ear bones) of returning adults indicated a dominance of the early spring parr-smolt life-history pattern. Quotes below in italics are from Sturrock et al.

- Fry emigration success has suffered from reduced winter flow peaks (In years lacking winter pulse flows, salmon tended to emigrate later, larger, and in lower numbers… predicted fry expression was 62% lower following major dam construction… Even marginal improvements to fry survival rates could significantly boost adult recruitment rates.” Winter flow pulses would increase the contribution of fry emigrants to recruitment.

- Parr and smolt emigration success benefitted from CVPIA/VAMP Apr-May prescribed storage releases and reduced south Delta exports. “Peak parr emigration in April coincided with managed releases intended to improve downstream survival.” Continue these early spring prescriptions.

- Late spring smolt emigration survival has been very low due warm water temperatures and low flows. Late spring pulse flow prescriptions would increase the contribution of older smolt emigrants to recruitment.

- “[S]trong suppression of any life‐history diversity—whether evolved or plastic— could have serious demographic and evolutionary consequences… negative population growth in the absence of demographic rescue by hatchery strays.” Without flow pulses in winter, early spring and late spring, the population is at risk of significant decline and loss of genetic integrity. Hatchery strays will further dominate the population and production of wild fish will decline.

Other measures suggested by Sturrock et al. (2019) included:

- Increasing fry floodplain habitat downstream of the Stanislaus to increase fry emigrant success and the contribution of the fry emigration component of the life history portfolio to adult recruitment. “Given the substantial numbers of fry often produced, even marginal increases in their survival rates would have significant impacts on recruitment.”

- Increasing the portfolio diversity for other Central Valley salmon populations will reduce the overall risks to Central Valley fall run salmon because “[a]djacent watersheds often experience similar climates and manage their dams for similar goals, which could homogenize emigration timings among nearby populations. Shared bottlenecks such as the Sacramento‐San Joaquin Delta could further compress emigration timings, increasing the risk of match‐mismatch events in the ocean.”

In conclusion, the Stanislaus River fall-run salmon population dynamics provide important lessons for sustaining wild salmon in the Central Valley. Sustaining life history diversity will increase salmon recruitment per spawner. It will also reduce risks of population declines and loss of genetic integrity in the wild component of salmon populations.

Figure 1. Stanislaus River fall-run Chinook salmon run (adult escapement) estimates 1952-2018. Note completion date for New Melones Dam in red. Data source: CDFW.

Figure 2. Spawner-Recruit relationship for fall-run Chinook for the Stanislaus River. Number represents recruit year (escapement for that year). Color represents water year type for San Joaquin basin during brood year rearing (two years prior). Blue is wet year. Red is dry-critical year. Green is normal year. Red circle is for poor ocean rearing conditions and/or poor river flows during spawning run. For example: year 08 represents 2008 recruitment (escapement) from 2005 spawners (both log10 -1 transformed); blue represents wet year 2006 during river rearing; red circle represents poor ocean rearing and poor river flows during 08 spawning run.

Figure 3. Stream flow in the lower Stanislaus River near Ripon in 2007-09 and 2013-15 drought years. Note prescribed reservoir releases in April-May 2013 and 2014 and October of most years.

Figure 4. Stream flow and water temperature in the lower Stanislaus River at Ripon and Orange Blossom Bridge in wet year 2017. Note water temperatures below 60oF are optimal for fall spawning. The strong spring flow pulse should lead to good 2019 adult recruitment.

- Flood releases are rare in the Stanislaus watershed, where storage capacity is twice annual average runoff. ↩