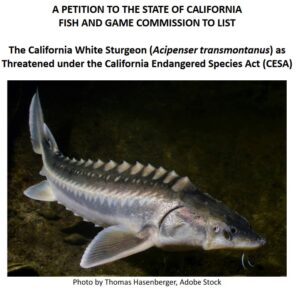

On November 30th, 2023, San Francisco Baykeeper, California Sportfishing Protection Alliance (CSPA), the Bay Institute, and Restore the Delta petitioned the California Fish and Game Commission to list the state’s white sturgeon as “threatened” under the California Endangered Species Act. The coalition also petitioned United States Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and NOAA Fisheries to list California’s white sturgeon as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act.

On November 30th, 2023, San Francisco Baykeeper, California Sportfishing Protection Alliance (CSPA), the Bay Institute, and Restore the Delta petitioned the California Fish and Game Commission to list the state’s white sturgeon as “threatened” under the California Endangered Species Act. The coalition also petitioned United States Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo and NOAA Fisheries to list California’s white sturgeon as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act.

San Francisco Bay and parts of its watershed are home to California’s only population of reproducing white sturgeon. Since the early 2000’s, writes Robin Meadows, white sturgeon abundance has dropped by two-thirds. San Francisco Baykeeper science director Jon Rosenfield said that the Bay’s white sturgeon population “has experienced a persistent and dramatic population decline because state and federal agencies allow too much fresh water to be diverted from the Bay’s Central Valley tributaries to supply industrial agriculture and large cities.”

Mismanaged water, pollution, algal blooms, and overharvest are “speeding the white sturgeon down the road to extinction.” The coalition’s petitions state that “these problems are independent of each other – addressing just one or two of these major problems will not eliminate the high risk” that the Bay’s white sturgeon will become endangered. The coalition also said that protecting the Bay’s white sturgeon from extinction requires “a coordinated response to these individual and collective threats.”

Key Features of the White Sturgeon’s Life Cycle

White sturgeon are large, resilient fish that can weigh up to 500 pounds and can live for up to a hundred years. The coalition’s petition states that the long lifespan of white sturgeon has historically enabled them to “persist and maintain a relatively stable population through periods where riverine spawning and early rearing habitats were unsuitable,” such as drought conditions. On the other hand, white sturgeon can take up to 19 years to reach reproductive maturity. Thus, “Reliably high adult survival is essential to the success” of the population.

The Bay’s white sturgeon spend most of their lives in saltwater but return to deep freshwater to spawn. White sturgeon can spawn multiple times within their lifespan but do not spawn every year. As stated in the petition, “Successful reproduction occurs episodically, when spring-summer river flows are high enough to support incubation and early rearing success.”

The Role of Water Management in the Decline

The Bay’s white sturgeon population can withstand naturally occurring droughts, but it cannot withstand, as stated by Gary Bobker of the Bay Institute, “California’s disastrous water management policies.”

The Newsom Administration continues to move ahead with water policies and developments that will divert more water away from the Bay. Sites Reservoir and the Delta Conveyance Project (Delta tunnel) are two of these developments. The petition states that if Sites Reservoir and the Delta tunnel come to fruition, they would “reduce the frequency and magnitude of high spring-summer Delta inflows and outflows.” This in turn would reduce the “frequency and magnitude” of successful white sturgeon reproduction.

The State Water Resources Control Board has admitted that “existing requirements for water quality and flow” do not adequately protect white sturgeon and other native fish. While the State Board has issued a draft staff report that proposes new flow standards for the Bay-Delta estuary, the petition states that the new standards as proposed will still fall short in providing white sturgeon with the flow conditions they need to “sustain their populations and fully recover.”

The State Board has also allowed a consortium of water users to propose “Voluntary Agreements” as an alternative in the standard-setting process. These agreements among state water contractors and agencies would provide far less flow in the Delta and its tributaries than the State Board’s proposed new standards.

Algal Blooms in the Bay Have Killed Hundreds of White Sturgeon

Over the past two years, there have been catastrophic algal blooms in the greater San Francisco Bay that caused the death of hundreds of mature white sturgeon.

Nutrient-rich effluent from nearby municipal wastewater treatment plants and oil refineries have made the Bay “one of the most nutrient-enriched estuaries in the world.” In the summer of 2022, an algal bloom dubbed the “red-tide” struck the Bay.

High nutrient levels, warm temperatures, and low water flows provided the perfect conditions for the alga heterosigma akashiwo to flourish. This alga depletes oxygen in water, creating fatal conditions for fish and wildlife.

Paul Richards reported that “volunteers counted 400 dead white sturgeon after the red-tide event.” This number only represents a portion of suspected deaths as “sturgeon tend to sink after they die.”

State officials claimed that climate change was the primary cause of the red-tide event. Indeed, 2022 was a dry year, but it was followed by a very wet 2023. Despite the abundant water in 2023, another, though less severe, red-tide event occurred in the Bay.

In a press release responding to the 2023 event, Tom Cannon, an estuarine fisheries ecologist with California Water Impact Network, said, “Unlike 2022, Shasta is now full. The water contractors are getting everything they want and more. Every almond and pomegranate tree in the Central Valley is just sopping with water. There’s enough water for the salmon. Enough for the sturgeon. They’re just not getting it.”

Cannon went on to say that there “were maybe 10,000 sturgeon in the estuary before these events. The total population is certainly a fraction of that now. The Bay’s sturgeon population simply can’t take these kinds of hits and survive. They need more water, and they need it right now.”

How Fishing Fits into the Overall Decline

Insufficient freshwater flows in the Delta and its tributaries have led to low rates of successful white sturgeon reproduction. Algal blooms and poor water quality, especially in the Bay, threaten remaining adult white sturgeon. In these conditions, the white sturgeon population is “highly sensitive to overharvest.”

Commercial fishing of the Bay’s white sturgeon “peaked in 1887, with a haul of more than 1.5 million pounds.” By 1917, the state banned commercial fishing of white sturgeon due to a stark population decline. In 1954, the state permitted recreational fishing of the Bay’s white sturgeon.

Currently, the state permits recreational anglers to catch one fish per day within a specified size range and three fish annually. The petition states that the best available science provides no evidence that these harvest levels are sustainable. The coalition advocates for the state to restrict recreational fishing of the Bay’s white sturgeon to catch and release only.

Chris Shutes, executive director of CSPA, said, “Bad water management is devastating California’s fisheries, and people who fish are left to shoulder far too many of the consequences.” Yet he maintains some hope: “There’s still a chance for sturgeon to be plentiful and rebound.”

And thus, the Endangered Species Acts

To save this ancient fish, the Newsom Administration and relevant state and federal agencies must address excessive freshwater diversions, pollution, algal blooms, and overharvesting. Their failure to take decisive action is why petitioning organizations have turned to state and federal endangered species acts to protect white sturgeon.