Article from Sacramento Bee.

http://www.sacbee.com/news/state/california/water-and-drought/article34197762.html

By Phillip Reese and Ryan Sabalow

September 5, 2015

A year ago, California lost nearly an entire generation of endangered salmon because the water releases from Shasta Dam flowed out warmer than federal models had predicted. Thousands of salmon eggs and newly hatched fry baked to death in a narrow stretch of the Sacramento River near Redding that for decades has served as the primary spawning ground for winter-run Chinook salmon.

Earlier this year, federal scientists believed they had modeled a new strategy to avoid a similar die-off, only to realize their temperature monitoring equipment had failed and Shasta’s waters once again were warming faster than anticipated.

In the months since, in what is essentially an emergency workaround, they’ve revised course, sharply curtailing flows out of Shasta. The hope is that they reserve enough of the reservoir’s deep, cold water pool to sustain this year’s juvenile winter-run Chinook. But it’s meant sacrificing water deliveries to hundreds of Central Valley farmers who planted crops in expectation of bigger releases; and draining Folsom reservoir – the source of drinking water for much of suburban Sacramento – to near-historic lows to keep salt water from intruding on the Delta downstream.

In spite of all this, another generation of wild winter-run Chinook salmon could very well die.

For all the focus on fallowed farm fields and withered lawns in California’s protracted drought, native fish have suffered the most dire consequences. The lack of snowmelt, warmer temperatures and persistent demand for limited freshwater supplies have left many of the state’s reservoirs – and, by extension, its streams and rivers – hotter than normal. The changing river conditions have threatened the existence of 18 native species of fish, the winter-run Chinook among them.

Chinook are called king salmon by anglers for a reason. They can grow to more than 3 feet in length, and the biggest can top more than 50 pounds. Decades ago, before dams were built blocking their traditional spawning habitat, vast schools of these silver-sided fish with blue-green backs migrated from the ocean to spawn and die in the tributaries that feed the Sacramento River in runs timed with the seasons.

The largest run that remains in the Sacramento River system is the fall run, which survives almost entirely due to hatchery breeding programs below the Shasta, Oroville and Folsom dams. The winter run, in contrast, is still largely reared in the wild, laying its eggs in the gravel beds below Shasta’s concrete walls. Their numbers have dwindled in the face of predators and deteriorating river conditions. The federal government declared the run endangered in 1994, and it has flirted with extinction ever since.

Following last year’s failed federal efforts, only about 5 percent of the winter-run Chinook survived long enough to begin to migrate out to sea. The species has a three-year spawning cycle, meaning that three consecutive fish kills could lead to the end of the winter run as a wild species. One hatchery below Lake Shasta breeds winter-run Chinook in captivity.

Officials with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which operates both Shasta and Folsom dams, say they believe their emergency efforts at Shasta are working and they anticipate “some” winter-run Chinook will survive this year.

“We believe that we are on track,” said bureau spokesman Shane Hunt. “We are sitting in a much better place today than we were a year ago today.”

Several biologists interviewed remain dubious. They note that preserving more cold water in Shasta has meant many stretches of the Sacramento River are warmer than they were last year. They worry that salmon eggs and fry will still die – only gradually instead of suddenly.

“We stand a pretty good chance of losing the wild cohort again this year, like we did last year,” said Peter Moyle, a UC Davis researcher and one of the nation’s leading fisheries biologists. “If we get lucky some of those fish will survive. We’re definitely pushing the population to its limits.”

Agricultural leaders, meanwhile, say there’s good reason to suspect the government models will again prove flawed and the fish will die despite the sacrifices farmers have made.

Rep. Jim Costa, a Democrat and third-generation farmer who represents a wide swath of the San Joaquin Valley, is among those who think there’s a good chance farmers have been punished for no benefit to the fish.

“That begs the question: What are we accomplishing?” Costa said. “We are in extreme drought conditions. … The water districts that I represent in the San Joaquin Valley have had a zero – zero – water allocation. … Over half a million acres have been fallowed … It just seems to defy common sense and logic.”

Some members of California’s fisheries industry also have lost confidence in the bureau, arguing the government has badly mismanaged its rivers. Beyond the very existence of a wild population of fish, they say, the government is risking millions of dollars for California’s economy and hundreds of fishing jobs – and a key source of locally caught seafood for markets and restaurants.

Two consecutive fish kills involving an endangered species could lead to more stringent regulation of commercial and recreational fishing. It’s a real possibility, state and federal fisheries regulators said, that salmon fishing could be severely restricted along much of California’s central coast and in the Sacramento River system next year.

Larry Collins, a commercial fisherman operating out of Pier 45 in San Francisco, said that in the fight over water, the fishing industry – and wild fish – lack the political clout compared with municipal and agricultural interests.

“I’ve been around a long time, and I’ve fought the battle for a long time, and I’ve watched the water stolen from the fish,” he said. “The fish are in tough shape because their water is growing almonds down in the valley. To me, it’s just outright theft of the people’s resource for the self-aggrandizement of a few, you know?”

“You got money you can buy anything,” he added. “You can buy extinction.”

Federal models prove faulty

On paper, the requirements for salvaging the winter-run Chinook seem fairly basic. The winter-run Chinook spawn from April to August. Juvenile fish swim downriver from July to March. If the water in the Sacramento River is too hot as the fry emerge from their eggs, they die. Warm water also makes it more difficult for the juveniles to survive their swim downstream to the ocean.

But in practice, there are broad variables to keeping the river cool, involving snowmelt, heat waves, water depths and the temperatures of the tributaries entering the reservoir, as well as conditions in the river downstream.

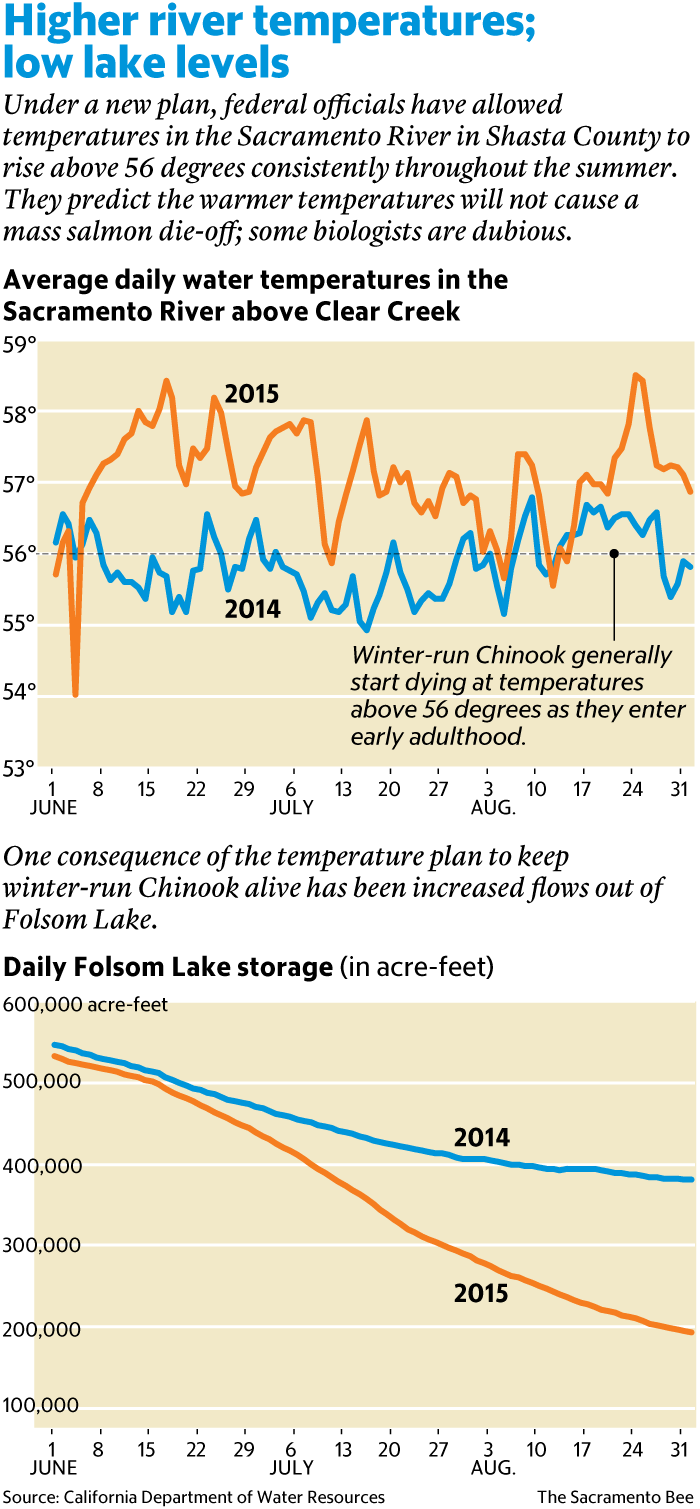

A year ago, federal and state officials had a plan to keep temperatures in key portions of the Sacramento River below 56 degrees; temperatures above 56 can trigger a die-off. The models built by the Bureau of Reclamation indicated operators could release large amounts of water from Lake Shasta while still maintaining a cool temperature, easing the pressure on farms and cities. According to their calculations, the water would be cold enough at key points in the Sacramento River to ensure survival of 30 percent of the salmon run.

But the models were wrong. The Bureau of Reclamation essentially ran out of cold water reserves in Lake Shasta, limiting its ability to control temperatures in the Sacramento River. Average daily river temperatures rose well above levels needed by salmon to survive. The 5 percent that did transition from eggs to fry were left to navigate to the ocean in tough conditions.

“That 5 percent – I guarantee you they didn’t make it down through the Delta,” said Bill Jennings, executive director of the California Sportfishing Protection Alliance.

Fast forward to this year, and another plan gone awry.

During the spring, government officials again said they would keep winter-run Chinook alive by maintaining water temperatures below 56 degrees. The State Water Resources Control Board signed off on their plan in mid-May.

Only weeks later, Bureau of Reclamation officials told the state that their temperature monitoring equipment wasn’t working. In fact, they said, temperatures in Shasta were warmer than anticipated – and dramatic intervention would be needed to keep winter-run Chinook alive. They asked the board to consider a new plan and immediately restricted flows from Shasta.

The state water board took up the issue at a meeting on June 16. Members of the board bemoaned their lack of good choices and later adopted a plan that left no one happy. Water releases would be curtailed out of Lake Shasta. Folsom Lake would be drawn to historic lows. Deliveries to farmers would be reduced.

And, despite those measures, the average daily temperature in the Sacramento River would rise to 57 degrees on most days and 58 degrees on some days, according to the government models. That’s too high a temperature for all winter-run Chinook to survive, but the Bureau of Reclamation, in documents supporting the change, said its modeling predicted roughly 20 percent of the fish would survive to early adulthood. That would be lower than a typical year – but not a disaster.

But are this year’s models more accurate? Already this summer, average daily temperatures at a key point in the Sacramento River have risen above 58 degrees on seven separate occasions, including several times in late August, state data show.

Federal officials said their models anticipated some temperature spikes, and noted that on each occasion so far, they were able to release cold water into the river and bring temperatures back down.

“It can have an effect” on fish, said Hunt, the bureau spokesman, of river temperatures above 58 degrees. But, he added, “That temperature is not a lethal temperature immediately.”

Jon Rosenfield, a biologist with the Bay Institute, disagreed, saying that many winter-run salmon likely were doomed by the temperature spikes. He offered the analogy of a chicken egg: “If you take an egg and dip it in boiling water, you are jeopardizing its ability to develop into a chick,” he said. “The longer you do that and the hotter the temperatures, the less likely it is to develop.”

Another concern is whether there is still enough cold water in Shasta to keep river temperatures low into the fall. Hunt says yes – that the government projects that Shasta will contain 350,000 acre-feet of cold water, below 56 degrees, at month’s end, far more than in 2014.

Rosenfield expressed doubts that the bureau is in position to do detailed calculations on its cold water supply. “They are way behind in anything using modern technology in measuring how much cold water they have,” Rosenfield said.

Scientists won’t know whether this year’s plan worked until fish surveys are completed in the winter. In a worst-case scenario, the government could rely even more heavily on its hatchery to sustain winter-run Chinook. Rosenfield called that option a “Band-Aid,” noting it would not preclude the loss of the fish as a wild species. Hatchery fish, he said, tend to come from a limited gene pool and may also have difficulty surviving in warm water.

Looking to the future

Jeff Gonzales worries about the ripple effects of another bad salmon season. Gonzales, a retired fire captain from Durham who guides clients on river-fishing trips, remembers when fisheries managers shut down the season for the fall-run Chinook in 2008 and 2009.

In those years, officials closed the fall-run fishing season in response to an unprecedented decline in the numbers of Chinook that had returned to the Sacramento, American and Feather rivers to spawn. The run plummeted amid poor ocean conditions and environmental problems in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta.

Gonzales thinks a similar scenario could be well underway, and that this year’s fall run is also in danger. He’s troubled by photos his fellow guides have sent him of fully-grown fall-run salmon floating dead in southern stretches of the Sacramento River. He attributes the deaths to warm water.

On Thursday morning, he was guiding clients on the river near Los Molinos, between Chico and Red Bluff, in search of fall-run salmon. The river is so warm, he said, that it’s been tough to find fish in his normal spots. The fish, he said, have either raced upstream seeking colder water, or are holding off the entrance to the Delta in the Pacific, waiting for a cold water flow.

That means slow-going for him and other guides.

On Thursday, his four clients, all firefighters enjoying an off-day, spent a four-hour stretch watching ospreys, wood ducks and herons glide by as their lures wriggled in the swift current. Every so often, a Chinook would breach the water and slap the surface with its tail, almost tauntingly. That morning, just one client saw his rod bend under the weight of a lunging 15-pound, silver-sided king.

Some clients have canceled trips because of the paltry catches, Gonzales said, and business will only get worse if the salmon seasons get shut down due to yet another winter-run die-off.

Maneuvering through the currents, the river rippling out before him, he lamented not just the loss of the fish but of a cultural heritage.

“You’ve gotta think about our future here, you know?” Gonzales said. “Our children and our grandchildren may not be able to see what we’re seeing here.”