Entrainment of fish into surface water diversions is a major anthropogenic cause of fish kill. Entrainment occurs when diversion works redirect flows from a natural channel into a pipe or canal, and aquatic organisms get directed or sucked into the artificial intake.

While rates of entrainment per diversion may appear insignificant, the cumulative rate of unintentional fish mortality as a result of entrainment is a cause for concern. Unscreened diversions disrupt migration and can adversely affect the overall survival of fish species. The California Department of Fish & Wildlife’s (CDFW) list of priority actions for fish migration improvement on the Delta Stewardship Council’s website includes many opportunities for screening diversions.

A diversion gate on a tributary to the Shasta River. Image: Damon Borgnino

Water distribution systems

California’s water infrastructure was built and codified in the 20th century, when unallocated water supplies were more abundant and competing demands for water were less intense. Well known as an engineering marvel that invigorates the fourth largest economy in the world, much of California’s water infrastructure dates to a time prior to the adoption of most laws that protect clean water and a healthy environment.

When infrastructure poses risks to fish and wildlife, it is important to retrofit the technological or operational underpinnings of the threatening practice.

An irrigation canal leading off of Parks Creek in the upper Shasta

Valley. Image: Damon Borgnino

What are fish screens and how common are they?

Wherever freshwater gets diverted from a river, creek, lake or reservoir, fish screens can help prevent juvenile and adult fish from entering water intakes and diversion canals. The size and expense of fish screens vary, depending largely on the amount and velocity of water flowing through the screen. Small diversions generally utilize screens that filter flows of less than 40 cubic feet per second (CFS) and cost thousands of dollars. Large diversions require screens that filter flows in excess of 250 CFS and generally cost millions of dollars.

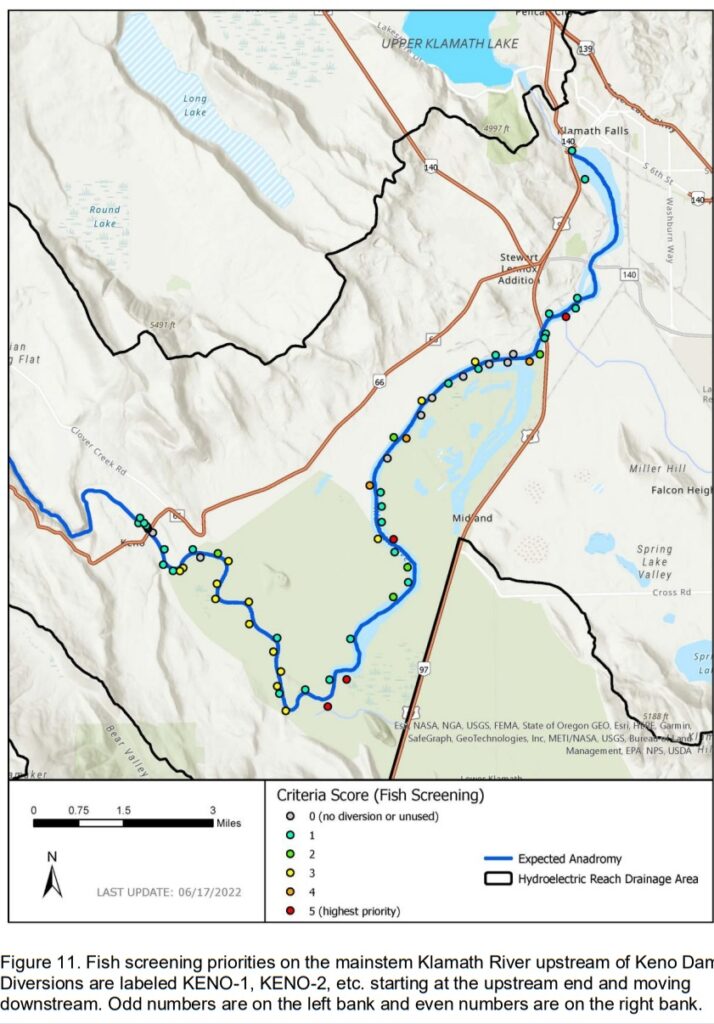

At the turn of the 21st century, approximately 3,400 diversions were drawing water from the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and their tributaries. Of those diversions, 98.5% were unscreened (Moyle, 2002). In the “Klamath Reservoir Reach Restoration Prioritization Plan” published in December 2022, 78 irrigation diversions were identified above the former Iron Gate Dam, only eight were equipped with fish screens.

Larger diversions are more likely to entrain or impinge substantial numbers of fish. Most larger diversions are also owned by major utility operations, such as power providers or irrigation districts, who can afford to install fish screens. Larger diversions are also generally associated with permitted activities, and are subject to higher levels of regulatory compliance. As a result, large diversions are more likely to be screened than medium or small diversions.

A map prioritizing unscreened diversions in the Klamath River mainstem.

Image: Klamath Reservoir Reach Restoration Report 2022

Regulating diversions to minimize ‘take’

Most surface water diversions were constructed prior to passage of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Thus, a vast majority of small to medium diversions lack the equipment necessary to protect biodiversity. At the state level, Fish and Game Code defines fish screen requirements for diversions constructed or altered post-1972 that may entrain listed species. FGC § 6021, FGC § 5988, and FGC 5992 establish CDFW’s authority to install fish screens where it is practical and necessary, requires bypass flows adequate for fish, and provides the department with an easement to access the site for screen selection, installation, inspection and maintenance.

At the federal level, the ESA, Federal Power Act (FPA), and the Fish & Wildlife Coordination Act all contain language that define fish screen requirements on diversions. The ESA is codified in Title 16, Chapter 35, U. S. Code § 1531. Section 9 states that removal of individuals of endangered species by any means, including diversions, constitutes “take”, and is prohibited. The Sec. 9, 4(d) rule provides flexibility for management of threatened species, as they are not automatically subject to the same prohibitions of Sec. 9 as endangered species. These protective regulations apply to small diversions as well as larger ones.

Many problems with unscreened small-to-medium irrigation diversions involve the monitoring of entrainment and enforcement of avoiding take. Unless a watershed is identified as important for supporting threatened or endangered species, environmental monitoring and law enforcement is often practically non-existent. Yet if a watershed is regarded as important habitat for supporting biodiversity, it is usually because the once-thriving ecosystem has become so degraded that regulators have started to pay attention, while vested interests remain entrenched.

Additional factors that influence the likelihood of fish getting entrained by diversions include the location of a diversion relative to fish habitat, percent of flow diverted relative to baseflow, and timing and duration of diversion relative to the migratory patterns of anadromous fish.

If the majority of a river is allocated to diverters, it is likely that the installation of fish screens alone will be insufficient to revitalize struggling fish species. Technological solutions, such as fish screens and fish ladders, can assist in species recovery if they accompany legitimate revitalization efforts to replenish river ecosystems.

American Kestrel takes flight in the Shasta Valley. Image: Damon Borgnino