Basking in the glow of Thanksgiving, I am grateful for the incredible strides made this year toward recovery of anadromous fisheries in the north state. Heightened returns of adult Chinook spawners to Battle Creek, to the Scott River, and to Klamath tributaries previously blocked by dams confirm that diligent efforts to improve fish passage and water quality can eventually produce results.

The three events in 2025 for which I am most grateful are: 1) substantial and near-immediate water quality and habitat improvements following the removal of the Klamath dams; 2) passage of AB 263, which secures minimum instream flow levels in the Shasta and Scott Rivers for another 5 years; and 3) the start of the 3-year clock for Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) to produce an application to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for decommissioning the Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project.

Recent events in the Klamath show that dam removal is an effective remedy

Klamath road sign after dam removal. Image: Angelina Cook

Within months of the initial sediment flush that followed removal of the Klamath dams, temperatures dropped, dissolved oxygen rose, turbidity declined, and conditions for harmful algal blooms in the mainstem essentially vanished. Decent numbers of Chinook, steelhead, lamprey, and even a few coho returned to spawn in tributaries upstream of the footprints of the reservoirs.

The fact that genetic memory can guide fish back to their indigenous spawning habitat after over 30 generations of dislocation is simply astounding. Some fish even passed ladders on the remaining Keno and Link River dams to return to their ancestral place of origin in Upper Klamath Lake tributaries. The take-home message to resound around the world is that dam removal works.

Next Stop, Shasta and Scott Rivers

Thankfully, the California Legislature and the California State Water Board also appear to be responding appropriately to salmon revival on the Klamath. They are enacting and enforcing streamflow requirements in the Shasta and Scott rivers, two major tributaries of the Klamath.

The FERC licensing process on the Klamath provided a scheduled regulatory review that a wide coalition leveraged to achieve dam removal. The Shasta and Scott rivers had no such mandated regulatory check-ins. Other legal mechanisms like basin adjudications, the Clean Water Act’s Total Maximum Daily Load process, and the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) have proven insufficient to date to reverse unsustainable water use on the Shasta and the Scott.

Consistent dewatering of tributaries and river reaches during the irrigation season motivated the State Water Board to implement emergency instream flow requirements in the Shasta and Scott rivers, first in 2021, and in each subsequent year to date. In 2024, a coalition led by the Karuk Tribe petitioned the State Water Board to initiate a rulemaking to enact permanent instream flow requirements for these rivers. Though the State Water Board denied this petition, the Board began a process to gather scientific information on flows needed in both rivers. The Board also announced that it intends to establish permanent instream flow requirements for these salmon-stronghold Klamath tributaries by 2030.

To minimize the expense and inefficiencies of emergency flow setting on an annual basis, the California legislature approved AB 263 in October 2025. The legislation establishes streamflow requirements for the Shasta and Scott for the next five years. The new law bridges the gap until 2030.

Aerial view of irrigated acreage adjacent to the Scott River, captured on an EcoFlight tour. Image: Ecoflight

Streamflow depletion from groundwater pumping in the riparian zone will also face limits with the implementation of the SGMA concept of Interconnected Surface Water through the establishment of numeric targets.

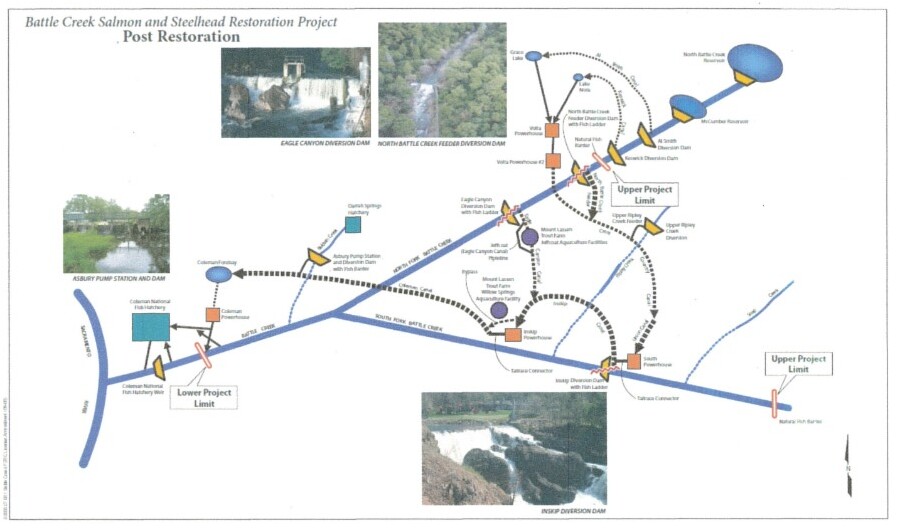

Unblocking Battle Creek

In the southernmost reaches of the Cascade Range, California’s largest electric utility has announced its plans to divest from Battle Creek. PG&E’s plan and schedule for decommissioning the Battle Creek Hydroelectric Project will become public when the private utility submits its License Surrender Application to the FERC. PG&E now has a May 2028 deadline for the Surrender Application. Fish advocates are working to address potential delays from FERC, PG&E, and the Coleman National Fish Hatchery. They also want to make sure local communities understand and benefit from the opportunities presented by PG&E’s departure.

Battle Creek drains the western slopes of Mount Lassen. It gains much of its flow from springs that originate on the mountain. Battle Creek flows into the Sacramento River south of the Shasta and Keswick dams. The abundant year-round cold water in Battle Creek makes it among California’s most promising prospects for Chinook salmon and steelhead recovery.

It is unknown whether all of PG&E’s dams on Battle Creek will eventually be removed. PG&E has been reviewing and retrofitting its Battle Creek Project since 1999. It has already removed many of its facilities. The Inskip Dam failed in 2022, and PG&E removed it last summer.

A second round (“Phase 2”) of restoration projects, planned years ago, will commence between 2026 and 2028. These restoration actions will eliminate fish passage barriers on the South Fork of Battle Creek. The decommissioning of the Project will have to address the facilities on the North Fork.

Battle Creek Salmon & Steelhead Restoration Phase 2. This map depicts a nearly free-flowing South Fork after completion of Phase 2 projects. Image: Battle Creek Restoration Program