For decades, stream flows in the Shasta River dropped to a fraction of historical levels every summer, no matter how wet the water year type. Now, a new law, AB 263, which took effect in September 2025, requires that sufficient quantities of water remain instream. This ensures that coho salmon will be less likely to go extinct as the State Water Resources Control Board works through the process of establishing permanent instream flow requirements.

The recent passage of AB 263 extends previous “emergency” minimum instream flow requirements in the Shasta River and the Scott River for another five years. It affords yet another opportunity for state and county agencies to do the right thing. During this time, the State Water Board is conducting a scientific basis report and an economic analysis. This work will determine the appropriate levels for permanent flows in these salmon stronghold Klamath tributaries.

Mount Shasta, seen from a survey tool used to measure the flow elevation of Big Springs Creek in September 2025. Image: Angelina Cook

While this is occurring, multiple efforts to measure flows in the Shasta River are underway. Local river advocates, who have endured decades of regulatory dysfunction and agency inaction, are preparing to advise this process. They are conducting independent scientific analyses of river hydrology with a combination of desktop methods and direct measurements. They are using as much measured flow data as possible. Instream flow studies for streams in alluvial basins can be developed using desktop methods alone. But steady springs emerging as groundwater in a volcanic basin form the backbone of Shasta River flows. A hybrid approach using both field data and desktop methods is optimal.

Dave Webb, founder of Friends of Shasta River, measures the channel perimeter to calculate unimpaired flow of the Shasta River. Image: Angelina Cook

Instream flows are usually measured by flow gages, generally installed and managed by federal or state agencies. The United States Geological Survey (USGS), the North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board (NCRWQCB), and the Department of Water Resources (DWR) are the primary agencies that record and convey flow data in far northern California. However, there are often gaps in gage locations and coverage of biologically important river reaches.

Accurate and up-to-date gage data is important, though not necessarily common. From these, one can generate “hydrographs.” A hydrograph shows instream flow measurements over time in a graphic format. Periods of record for stream gages vary extensively. Long-term datasets that record flows in strategic reaches of rivers are rare. Additionally, instream flows are substantially reduced during summer and fall months for irrigation use, so flow data alone is not sufficient. To inform the overall process, it is also necessary to estimate what the full natural or “unimpaired” flows would be.

Shasta River hydrograph illustrating instream flow rebound after the irrigation season. Image: U.S.G.S.

When agencies lack sufficient data in various reaches of a river, they often generate a model to approximate the accretions and depletions that inform a “water budget.”The State Water Board is working in coordination with the Shasta Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA), UC Davis, CSU Chico, and Larry Walker and Associates to develop such a model for the Shasta River. (For more information, see https://cwemf.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/10.3-Shasta-Watershed-Groundwater-Model-Foglia.pdf.)

Improving gage data is good, and models are valuable tools when gage data is not available. However, the absence of good flow data and the impulse to create a perfect model can become excuses for inaction in protecting public trust resources such as fish and rivers.

Instream flow requirements are generally established as a mitigation for major projects, like hydropower dams, that obstruct the natural flow and geomorphology of a river. The relicensing of dams under the Federal Power Act can establish instream flow requirements below dams to ensure sufficient deliveries of water for beneficial users downstream. Similarly, California Fish & Game Code Section 5937 is a state law requiring that water downstream of a dam be sufficient to keep fish in good condition. However, Section 5937 is not routinely enforced as part of a regulatory process.

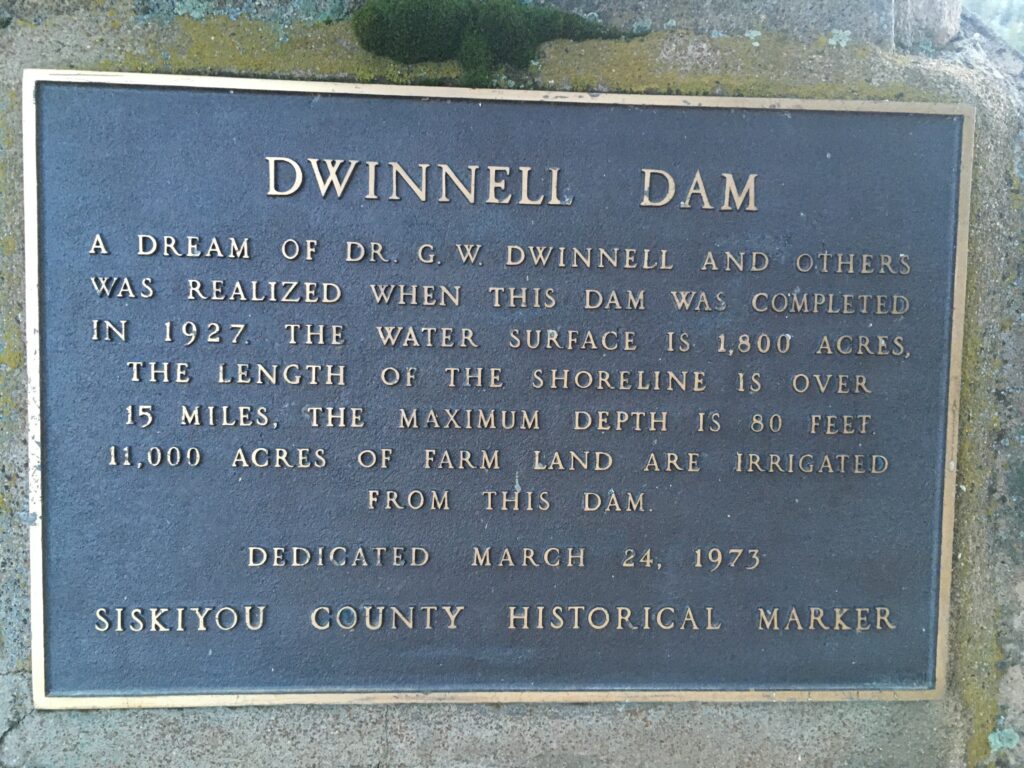

The plaque marking the history of Dwinnell Dam. Image: Angelina Cook

Stagnant water released from Shastina Reservoir with Dwinnell Dam in the background. Image: Angelina Cook

AB 263 is important because Dwinnell Dam and other diversions along the Shasta River are not subject to scheduled review by any regulator. The new law created a short-term mechanism to require official review of the flows downstream of Dwinnell Dam and those reduced by other diversions of water on the Shasta River.

The next opportunity to learn more about the State Water Board’s flow-setting process occurs on Tuesday, November 4. See https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/board_info/agendas/2025/nov/11_04-05_2025_agenda_links.pdf. Diverse interests may attend to advocate for adoption of permanent recovery-level instream flow requirements that are capable of supporting a harvestable surplus of fish.