In the Lagunitas Creek watershed of Marin County, the Olema-based nonprofit called Turtle Island Restoration Network (TIRN) is helping to increase the largest population of Central California Coast wild coho salmon. The program focused on this project is TIRN’s Salmon Protection and Watershed Network (SPAWN).

SPAWN has a staff of one full-time employee, several residential interns, and hundreds of volunteers. The program takes on a variety of projects, including cultivating native plants, re-creating floodplains, and building woody debris structures in streams to increase habitat complexity.

“In a good year, we see about 500 coho salmon spawn. There’s a lot of effort to stabilize this population,” said Todd Steiner, Founder and Special Projects Director of Turtle Island Restoration Network.

SPAWN began work in 1997. Every year, it engages in research and monitoring, habitat restoration, assisting local landowners, training volunteers, and acquiring land critical to assisting coho salmon. SPAWN also conducts creek walk tours, removes trash, and recreates lost floodplains and native riparian forests. It accomplishes this all within Marin County. Sometimes teams work close to neighborhoods. Other times they work in wild areas along the coast of West Marin.

SPAWN has taught volunteer Peggy Bannan that restoration is more complicated than it might seem.

“Essentially, we’re putting everything back the way Nature had it to begin with. You need thousands of different types of native plants, heavy machinery, and many hours of planning and groundwork,” said Bannan. She is a resident of San Geronimo Valley.

NoahLani Litwinsella, an associate attorney in the Denver office of the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, volunteered for SPAWN as a child. Today, he calls California’s salmon population a treasure.

“As the salmon contend with changing anthropogenic environmental conditions, habitat restoration can have a significant impact. Creating more favorable conditions for juvenile salmon is an efficient way to support the population for generations to come,” said Litwinsella.

Where SPAWN works

SPAWN focuses on the undammed tributaries of Lagunitas Creek and San Geronimo Creek. Both are in the Lagunitas Creek Watershed. San Geronimo Creek is the undammed headwaters of Lagunitas Creek.

This past year, SPAWN also worked in Redwood Creek in Muir Woods. This waterway is the next major watershed south of the Lagunitas Creek watershed.

“The Marin Municipal Water District monitors the main stems of Lagunitas Creek and San Geronimo Creek. (The) U.S. National Park Service monitors streams inside the Parks,” said Steiner.

SPAWN became involved because Central California Coast coho salmon are listed as an endangered species by California and the federal government. Commercial and recreational fisheries for coho salmon have been closed since the early 1990s. The Lagunitas Creek watershed supports 10 to 20 percent of the remaining population of this run of salmon. This makes preserving natural waterways and restoring habitat extremely important.

The work in Redwood Creek this fall focused on building and placing obstacles made of locally-collected woody debris in the creek. These barriers are called Post-Assisted Log Structures (PALS). They are held in place by posts driven into the creek bed. The PALS slow down the flow of the water in the creek. They also create shelters and refuge for young salmon in their first year and a half of life.

Using PALS is a new restoration technique that does not rely on heavy equipment. This is an advantage because it can be utilized in areas where workers could not get heavy equipment into a site. Yet PALS cannot be used in some sensitive areas. SPAWN accomplished the Redwood Creek PALS project by hiring Symbiotic Restoration, a Mckinleyville firm that provides training and implementation of PALS projects.

SPAWN helped U.S. National Park Service with the Redwood Creek project by providing resources and staff. This effort followed the October to November 2025 shutdown of the federal government and cutbacks to U.S. National Parks Service staff and Park resources.

SPAWN staff and volunteers, Symbiotic Restoration staff, and U.S. National Park Service staff assemble locally-collected wood in Redwood Creek in Muir Woods. Image: SPAWN

SPAWN staff and volunteers, Symbiotic Restoration staff, and U.S. National Park Service staff work together to build obstacles made of locally-collected woody debris in Redwood Creek in Muir Woods. Image: SPAWN

This winter, as in winters past, SPAWN is conducting spawning surveys. Spawning occurs during the rainy months, usually peaking in January. SPAWN will conduct out-migration surveys of juveniles (smolts) in the spring. That is when smolts migrate out to the ocean.

“The primary limiting factor for the recovery of coho salmon in this area is the lack of refuge habitat for juveniles in winter. Impermeable surfaces increase velocity, erode, and incise creek banks. [This threatens] juvenile survival during winter storm events,” said Steiner.

The verb “incise” here refers to a stream cutting its channel into the bed of a valley through erosion. An incised creek flows much faster than a non-incised creek. Incision makes a creek inhospitable to young salmon.

“The creeks have been cut off from their historical floodplains, causing juvenile mortality during storm events. This is a result of residential development. Instead of water infiltrating in the water table and slowly making its way to the creeks, it rushes straight off roofs, roads and parking lots straight into the creek,” said Steiner.

The water arrives at the creek traveling at high velocity.

“Young fish get caught by rushing waters. Because they can no longer escape into the slow moving water of the lost historical floodplains, they can be killed,” said Steiner.

The mechanics of water explain why SPAWN attempts to find spots that are clear of development to “remake” into floodplains.

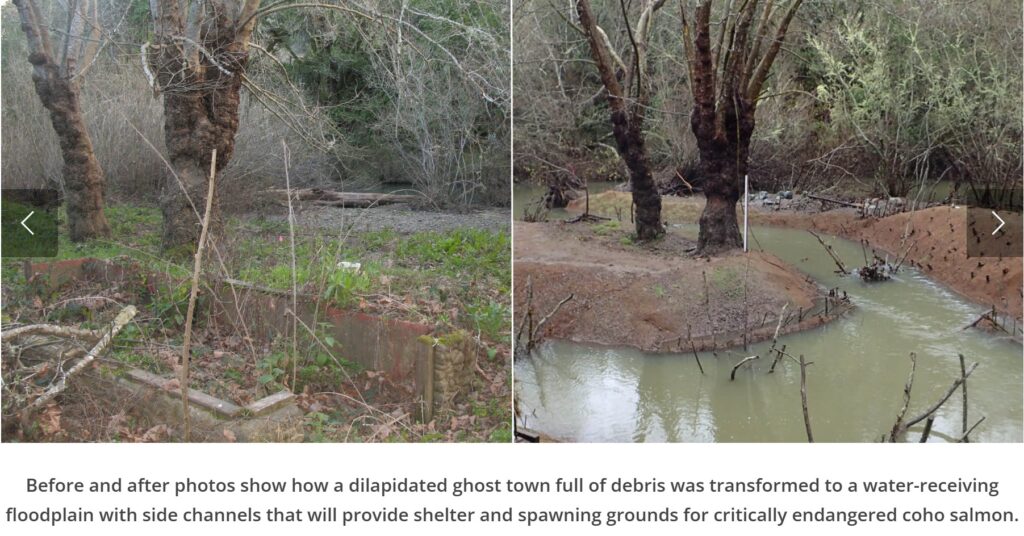

One such spot SPAWN worked on between 2018 and 2019 was Tocaloma, a ghost town three miles east-southeast of Point Reyes Station.

“Tocaloma was a stop on the Marin Northwestern Pacific Railroad, which traveled from Sausalito north through the county. We took out 25 million pounds of fill soil placed in the floodplain and removed abandoned retaining walls, houses and septic systems. [Then we created] a wild floodplain,” said Steiner.

In 2020, SPAWN modified the property that used to be the San Geronimo Golf Course. The 157-acre golf course was built in the 1960s. In 2017, a nonprofit called the Trust for Public Land acquired the property.

“We removed “Roy’s Dam” and created a water feature we call “Roy’s Riffles.” [This allows] salmon to easily migrate upstream. [The work] involved dismantling the dam and removing millions of pounds of sediment that had built up behind it over nearly 100 years. We widened some existing water channels to slow the water, created side channels, and installed large logs [woody debris structures] to increase habitat complexity and refuge for the salmon,” said Steiner.

SPAWN has also helped improve habitat on private property, such as in West Marin’s cattle ranchlands. This includes repairing dirt roads to keep fine sediment out of the creek. Fine sediment can bury and suffocate salmon eggs that are in gravel “redds,” or nests.

SPAWN frequently meets with landowners to show them how to make their creeks more fish-friendly. Such actions not only help salmon, they also help landowners by reducing the chances and severity of flooding.

Permits and outreach

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) permit all of SPAWN’s work. SPAWN sometimes requires permits from other agencies, including the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Marin County Department of Public Works, the California State Water Board, and other entities, depending on the project type. SPAWN works with federal, state, and local offices on plans and designs.

One of SPAWN’s hardest jobs is figuring out how to reduce pushback by some local residents. Some do not like government restrictions that affect how they can use their property.

It helps to do outreach through creek walks with schools and community members. It is also advantageous to distribute of native plants from the organization’s native plant nursery. Still, it can be difficult to let landowners know what actions work best for fish.

“A lot of residential property owners are fearful of government regulation. They don’t want to be told to move future development away from creeks. [They also don’t want to be told] that they should protect trees that shade the creek and keep the water cold and clean,” said Steiner.

For example, many local residents do not have a concern when SPAWN creates wood structures in Redwood Creek in Muir Woods. Yet even individuals who view this project and others like it express frustration when hearing that they should avoid building a second home on a property near a creek. They also are unhappy with the suggestion not to saw fallen trees near or in creeks near homes.

The best thing for the fish is to leave the downed trees in place to create shelters for fry and parr. To accommodate the community, fallen trees can often be re-situated to avoid flooding but still provide fish habitat.

One project that helped mitigate impacts of impervious surface runoff is the 10,000 Rain Gardens Project. SPAWN has helped residents set up cisterns and rain barrels to catch rainwater off their roofs. This prevents the water from running off the roof and becoming a high velocity stream that could strand young fish.

“If the residents save the water for irrigation, they can save money and help fish at the same time,” said Steiner.

SPAWN’s internship program is another popular way to do outreach. It helps young people in college and graduate school prepare for careers in the U.S. Forest Service, the U.S. National Park Service, and consulting businesses that relate to the natural environment.

“The work that SPAWN improves the environment for native fish species and many other species that live in or use the waterways. These include amphibians, insects, birds, and mammals. When SPAWN volunteers and interns assist with work in the field, they get a better sense of how modifications to the natural environment increase biodiversity,” said Steiner.

More first-hand stories of work with SPAWN

Peggy Bannan

Bannan, who moved to West Marin about 30 years ago, had heard about SPAWN’s efforts for decades. When she retired five years ago, she began volunteering in SPAWN’s native plant nursery.

This winter, she also joined a group that planted native plants near Chicken Ranch Beach in West Marin. Bannan’s recent service is part of a larger restoration effort that began earlier this year. The first step was putting in woody debris, to slow waterways rushing to the beach.

“The next step in making the area more stable is planting the native plants in spots that are appropriate for them, during December and January. That’s the rainy season,” said Bannan.

Kristen Hopper, SPAWN’s Native Plant Nursery Manager, walks ahead of the volunteers. She plants flags that denote what plants to install in different places. This helps volunteers see the conditions and environments best suited for native plants.

NoahLani Litwinsella

Litwinsella began volunteering with SPAWN in 2002, when he was five. He first became interested in salmon when he read a book about them in the Muir Woods gift shop.

“Soon after, my mom discovered SPAWN. We quickly became involved in all aspects of its work. This work was primarily split into two buckets, field research and public outreach,” said Litwinsella.

He counted adult salmon and their redds (nests) in the winter, smolts in the spring, and juvenile salmon in the summer.

“The data gathered from these studies inform policy, salmon habitat restoration efforts, and broader efforts to support the ecosystem,” said Litwinsella.

Litwinsella also guided groups to see spawning salmon. He continued this work through college.

Today, although Litwinsella’s legal career has taken him away from Marin County, he remains deeply committed to helping the salmon.

“My experience with SPAWN as an organization and with the salmon population underlying its work has been important to my ongoing support. It allows me to facilitate tailored legal assistance to the organization,” said Litwinsella.

SPAWN’s plans for the future

Going forward, preserving the local extinction of coho salmon in Marin County requires repairing land use mistakes of the past. It also requires enacting regulations to prevent repeating the mistakes in the present and future.

“This is an important step on the path to recovery that future generations will appreciate,” said Steiner.

He added that the work that is needed can be difficult to predict. Restoration can depend on new opportunities through land purchases or agreements.

“That’s why communication, a solid presence in the community, and outreach are all important. When people know what we’re doing to help coho salmon and why it works, there’s more of a chance that they will support SPAWN’s work. There’s even a chance they will get involved,” said Steiner.

NoahLani Litwinsella as a child, working on a salmon restoration project with SPAWN. Image: NoahLani Litwinsella

A coho salmon in a Marin County waterway in 2024. Image: NoahLani Litwinsella

For more information, visit: seaturtles.org/our-work/our-programs/salmon.