In 2025, The Wildlands Conservancy marked its first year of seeing coho salmon in a Sonoma coast stream called Russian Gulch. With luck and hard work, this event should herald a return of coho salmon in the Russian Gulch Watershed. The change was brought about by more than a decade of effort by Conservancy staff. They seek to transform the waterways of Jenner Headlands Preserve (the Preserve) into strongholds for salmon and other native fish species.

Coho salmon at Jenner Headlands Preserve. Image: Corby Hines

The Wildlands Conservancy is a San Bernardino County-based nonprofit that has owned and managed the 5,630-acre property since 2013. The Jenner Headlands Preserve is one of the Conservancy’s 24 preserves across California, Oregon, and Utah.

The Conservancy acquired Jenner Headlands Preserve in 2009, as a result of a dedicated four-year effort by the Sonoma Land Trust and Sonoma County Ag + Open Space. Additional funding for the acquisition came from the California Coastal Conservancy, the California Wildlife Conservation Board, the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the U.S. Forest Service’s Forest Legacy Program, and private donors.

Restoration was necessary because the waterways in the Preserve were severely damaged by logging activities, including the building and continued use of logging roads.

“Prior to the 1940s, logging on the parcel had not been heavy-handed. The most significant logging took place following WWII. The logging resulted in a clearcut landscape by 1965. Periodic logging continued on the landscape until the 1990s,” said Ryan Berger, Sonoma Coast Preserve Manager for The Wildlands Conservancy.

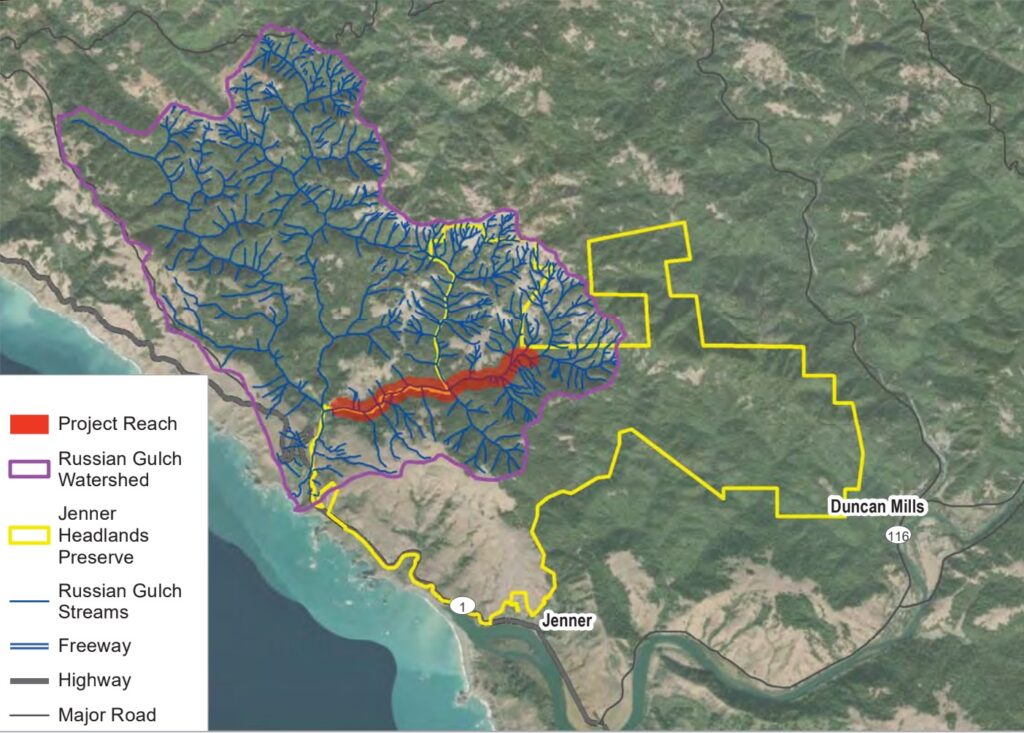

A map showing the Russian Gulch Watershed and the parcel comprising the Jenner Headlands Preserve. Image: East Branch Russian Gulch Fish Passage Barrier Removal Project, Final Project Report, by The Wildlands Conservancy

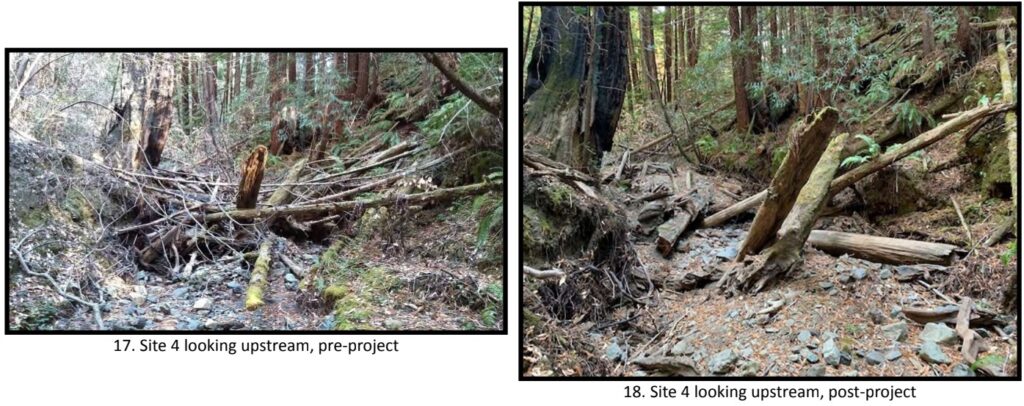

The Conservancy began engaging in grant-funded removal of barriers of large woody debris in 2019. This debris had created barriers for juvenile and adult salmon. The work involved electrofishing (aka e-fishing), a process to stun fish so they can be held during debris removal. It also required heavy machinery to take out material that was too heavy or dangerous for people to handle.

“When we started the debris removal, we began monitoring the different locations and identifying areas where salmon are likely to come. In 2025, when we confirmed having coho salmon on-site, that attracted a lot of attention from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW). They came to the Preserve to complete field surveys and talk with us,” said Luke Farmer, Regional Director of Sonoma Coast and Eel River Canyon Preserves for The Wildlands Conservancy.

The Conservancy looks forward to a partnership with CDFW going forward. This could involve additional field surveys and habitat restoration consultations.

An excavator removes large woody debris from the right bank of a waterway and places it above the active channel, within Jenner Headlands Preserve. Image: East Branch Russian Gulch Fish Passage Barrier Removal Project, Final Project Report, by The Wildlands Conservancy

Creating a better home for fish

Jenner Headlands Preserve is located in the hills directly northeast of the town of Jenner. The Sonoma Coast Regional Office of the Conservancy is situated on Jenner Headlands Preserve, overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The parcel contains a variety of environments, including redwood and Douglas fir forests, oak woodlands, chaparral, and coastal prairie.

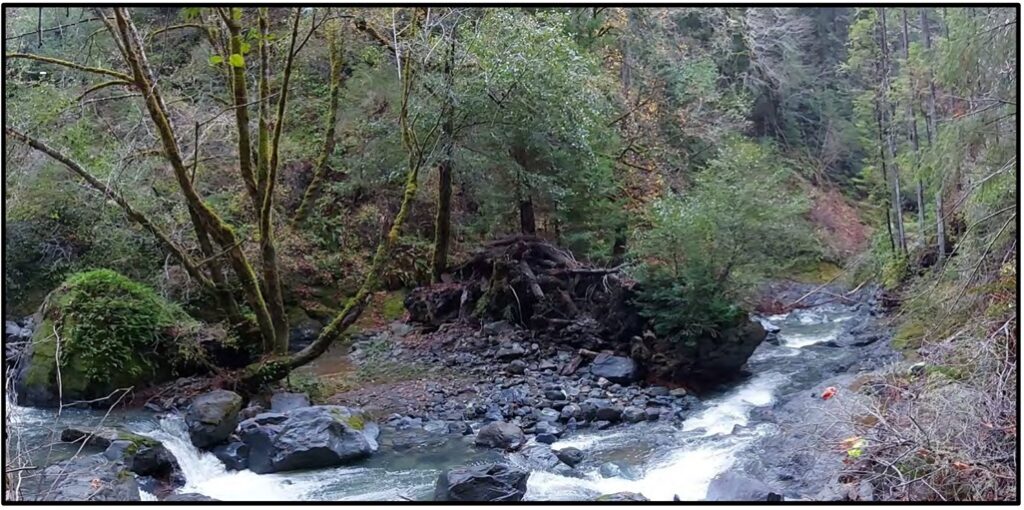

The East Branch of the Russian Gulch watershed forms the northern boundary of the Preserve. The East Branch combines with the West and Middle branches of this watershed to form the mainstem. The Russian Gulch mainstem flows out to the Pacific Ocean. Since the Preserve contains much of the East Branch, the Conservancy staff focus on this waterway.

The public is allowed to visit the Preserve free of charge and hike dirt trails in the area. Many of the trails are in drier areas of the parcel. However, the Russian Gulch Trail runs parallel to the East Branch. In addition, the Sea to Sky trail crosses a tributary of the East Branch at one point on the climb to Pole Mountain.

The restoration project sites are not in areas that public can access. This means the public does not get a deep sense of how the streams are being transformed. Understanding the changes the Conservancy is making involves learning the history of the Preserve.

First the prior owners clear-cut redwoods and Douglas fir, in the forests. The logging debris and broken trees stacked up in the Preserve’s waterways, creating logjams. Then the owners cut the secondary growth. This further increased the amount of debris.

“When the owners allowed that, they permitted the redwood root balls to run into the waterway drainages,” said Berger.

After the trees were gone, the soil near waterways became less firm. That soil became more prone to erosion by wind, river action, and rain. The streams filled with sediment and became muddier. The water in the streams also got hotter. There was less or no foliage hanging over them.

All of these factors discouraged salmon and steelhead. The fish prefer cool, clear streams. The Conservancy determined how to address the problems by hiring experts and developing technical advisory councils skilled in watershed management. The professionals recommended upgrades to the road system to reduce sediment inputs into the stream and improve overall habitat.

The Conservancy received the recommendations in a document called the Integrated Resource Management Plan. Then the organization developed the East Branch Russian Gulch Fish Passage Barrier Removal Project. It completed this project in 2019. The Conservancy monitored the area modified in this project until 2021.

Pre-and post-project work at one site to clear large woody debris from a waterway, in Jenner Headlands Preserve. Image: East Branch Russian Gulch Fish Passage Barrier Removal Project, Final Project Report, by The Wildlands Conservancy

A waterway in Jenner Headlands Preserve. Image: East Branch Russian Gulch Fish Passage Barrier Removal Project, Final Project Report, by The Wildlands Conservancy

Explaining what aids restoration

After the Conservancy removed much of the debris from streams, staff had to determine how to put some of it back. A low volume of woody debris creates hiding spots in the streams. Such spots provide cover for young fish to live and mature.

“Without hiding spots, a river otter can come through and wipe out an entire pool of fish. We want to avoid issues like that,” said Berger.

The hiding spots assist the Conservancy in taking a “hands-off” approach to predators of fish. The list includes river otters, raccoons, American minks, and wading birds like herons and egrets.

“Salmon are a good fatty meal, especially if they’re trapped in a pool,” said Berger.

In the winter of 2025, Conservancy staff received a report from a local fisherman of a dead adult coho salmon in the tributaries of the Russian Gulch.

“Young coho may imprint on their natal streams. If they survive their out-migration at sea, they may return to the Russian Gulch to spawn. Also, in June and July 2025, we did snorkel surveys with CDFW. We documented 239 coho salmon,” said Berger.

Krysten Kellum, Information Officer of the Office of Communication, Education and Outreach for California Department of Fish and Wildlife, added that 408 juvenile steelhead were documented in waterways on Jenner Headland Preserve in summer 2025.

Going forward, the Conservancy wants to collect data about native fish species from multiple seasons. Recently, multiple years of significant rain have benefited the Conservancy’s work. Rain contributes to full waterways, with clean and hopefully cool rushing water.

“These factors give the sign to salmon to come and remain in the tributaries,” said Berger.

Heavy rains also assisted in the winter of 2018/2019. They removed about half of the large woody debris jam at a particular site. This made it unnecessary for the Conservancy to engage in remediation there.

The Conservancy receives assistance to fight erosion from the California Native Plant Society (CNPS). The CNPS has given the Conservancy native plants, including willows, wild rose, and juncus, to plant in the Preserve.

The Conservancy partners with the Kashia Band of Pomo Indians (Kashaya Pomo). The Kashia Band of Pomo Indians is a federally recognized Tribe of Pomo people,

“The Preserve is on their ancestral land, so they know the area well. They have come to visit the Preserve and teach us about specific plants, such as the California nutmeg tree (California torreya). They explain what these plants are used for, how to make tools or instruments out of them, and what place they have in the environment,” said Berger.

At a later point, the Conservancy may determine whether a site in the floodplain surrounding the mainstem may be a suitable spot to reintroduce beaver. A condition of such a project would be available funding. A backup of water at the site could keep young salmon safe in pools.

One benefit of the Conservancy’s work at the Preserve is that the Preserve is a demonstrational property. That means successes here will inform similar projects elsewhere.

The Conservancy receives advice and ideas about its projects from other entities, including Sonoma State University (SSU). SSU manages the Pepperwood Preserve, a 3,000-plus-acre parcel in the Mayacamas Mountains between Santa Rosa and Healdsburg. This relationship is particularly beneficial because both entities maintain and improve parcels in the hills.

In the future, Conservancy may lead free public programming efforts to showcase some of this work in areas of the tributary that are accessible to the public.

Conservancy staff used a photarium to photograph and measure fish lengths before release. Image: East Branch Russian Gulch Fish Passage Barrier Removal Project, Final Project Report, by The Wildlands Conservancy