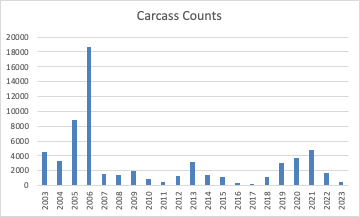

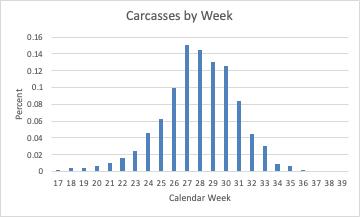

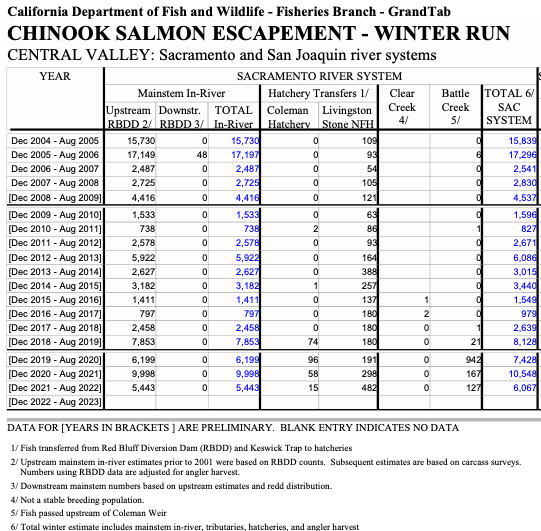

The latest carcass count survey indicates another near-record low-run of winter-run salmon in the upper Sacramento River in 2023 (Figure 1). Most of the spawning occurred in June and July 2023 (Figure 2). The official total winter-run escapement includes hatchery returns, Battle Creek counts, and fishery harvest, but is not available yet for 2023 (Figure 3). The low 2023 spawning census count can be directly attributable to broodyear 2020’s poor spawning, incubation, rearing and emigration conditions in below normal water years 2020 and critically dry year 2021.1

Broodyear 2020 started as eggs and milt in their parents in winter-spring of 2020. They were spawned and hatched in summer 2020. They began moving downstream in late fall 2020, rearing and emigrating in the lower river and Bay-Delta, and finally reaching the Bay and ocean in winter-spring of critically dry year 2021. The juveniles that survived returned as three-year-olds in winter-spring of 2023.2 Broodyear 2021 (two-year-olds in the 2023 run) were also subjected to drought conditions, spawning, rearing, and emigrating in 2021 and 2022 before returning in 2023.

Major stresses on young broodyear 2020 salmon included:

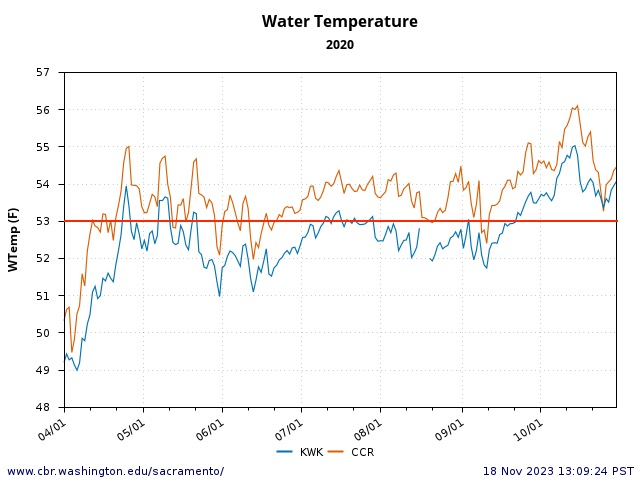

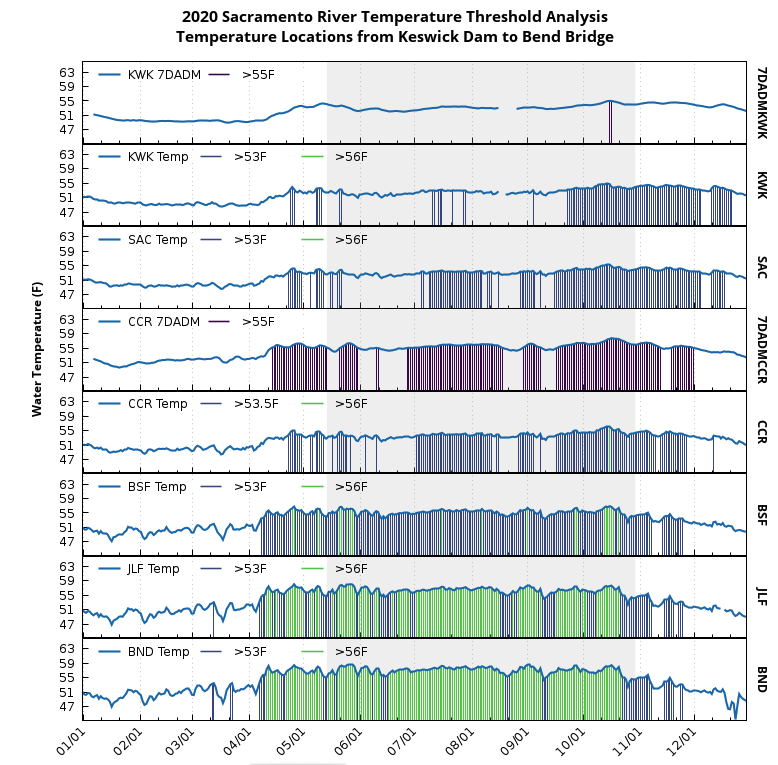

1. Broodyear 2020 spawners and their eggs and embryos were subjected to less-than-optimal water temperatures during the May-August 2020 spawning season (Figures 4 and 5).

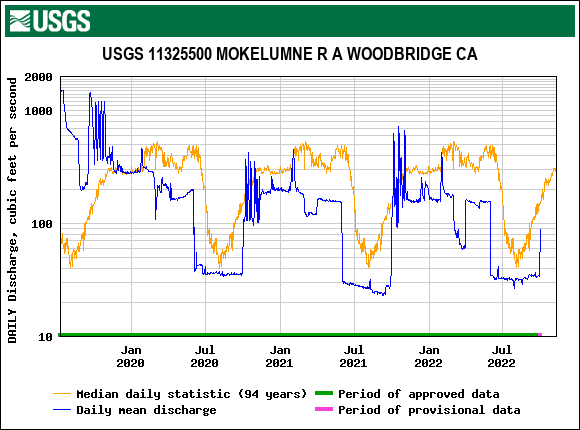

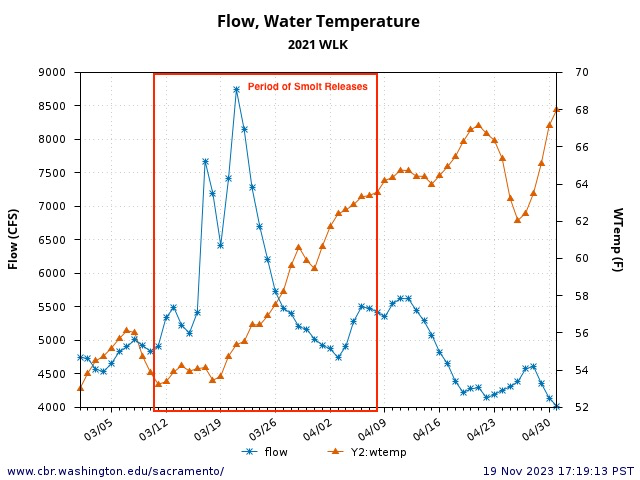

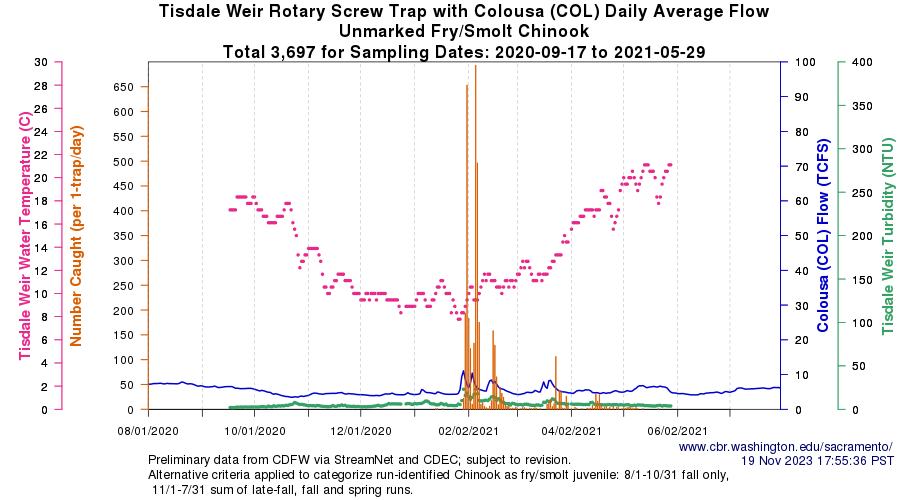

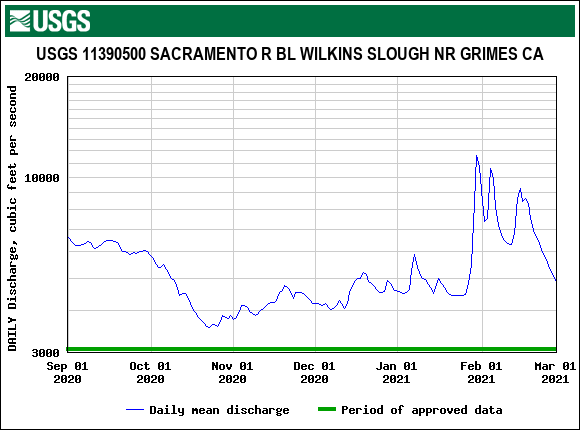

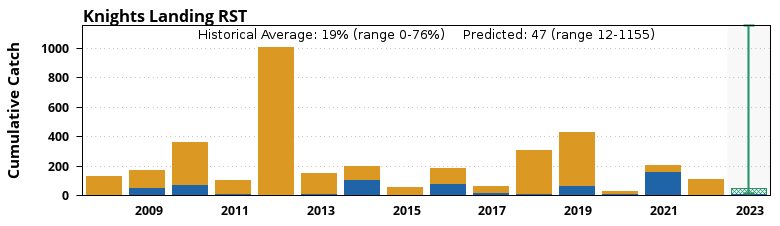

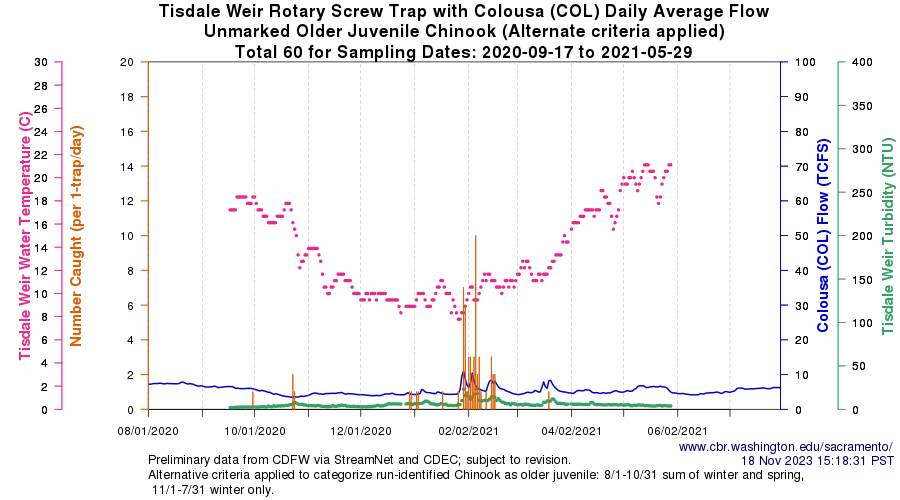

2. Flows remained very low from September 2020 through January 2021 (Figure 6). Water temperatures were also stressful during fall 2020 (see Figure 5). Without flow pulses in fall and winter, young winter-run salmon survival was poor (Figure 7), with delayed emigration (Figure 8).

Major stresses on adult salmon from broodyear 2020 that returned to spawn in 2023 included:

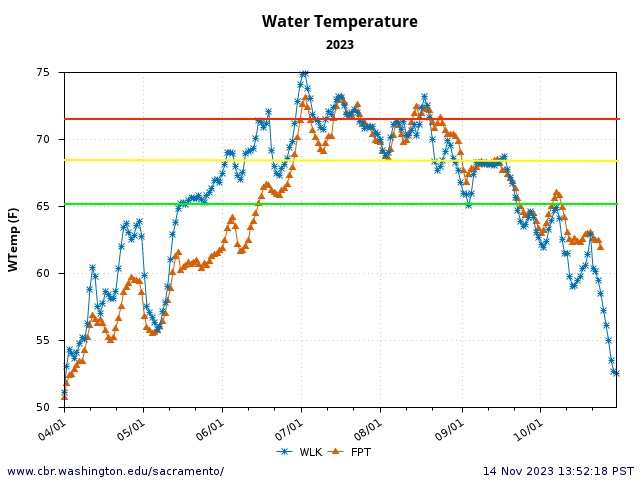

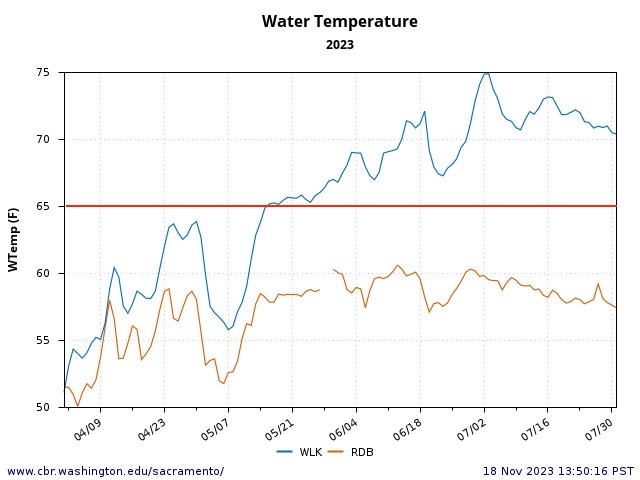

3. Upon returning in spring 2023 to spawn, broodyear 2020 adults were subjected to stressful water temperatures in May and June in the lower Sacramento River (Figure 9).

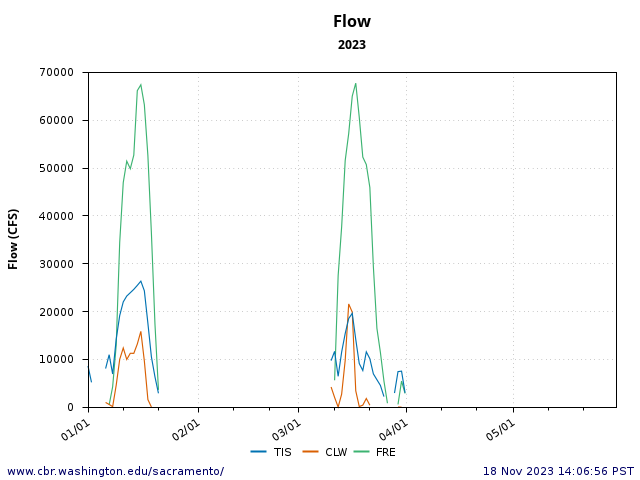

4. During the adult winter immigration period, two two-week-long flood events resulted in about half the Sacramento River flow passing into the Sutter and Yolo Bypass via overflow weirs (Figure 10). Large numbers of adult winter-run from broodyear 2020 were likely attracted into the flow from these bypasses. Those passing upstream via the bypass channels are subject to being blocked at the overflow weirs or stranded in bypass channels. Large fish passage “notches” are currently being constructed at the larger Tisdale and Fremont Weirs, but they are not expected to be operational until late in 2023 at the earliest. Large numbers of adult winter-run from broodyear 2020 were likely lost in the bypasses in winter 2023, as they were in past wet years.

In summary, poor numbers of winter-run broodyear 2020 spawners returned to the Sacramento River in 2023 despite the fact that the ocean and river salmon fisherieswere closed under an emergency order. The low numbers of spawners is attributable to poor river conditions in 2020 during spawning, rearing, and emigration, and in 2023 during the adult run up the Sacramento River in winter-spring.

Figure 1. Winter-run salmon carcass counts in spawning reach near Redding from 2003-2023. Five lowest tallies occurred two years after critical drought years 2008, 2009, 2014, 2015, and 2021. Source: USBR

Figure 2. Carcass counts by calendar week in 2023. Peak counts were in July (weeks 27-30). Source: USBR

Figure 3. Winter-run salmon escapement includes the carcass survey, hatchery returns, and Battle Creek returns. Source: CDFW GrandTab.

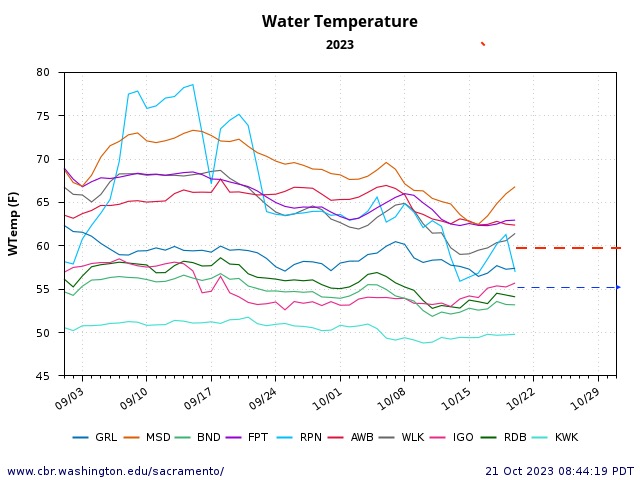

Figure 4. Water temperature in the Sacramento River in 2020 below Keswick Dam and above the mouth of Clear Creek – the upper ten miles of river in which winter-run salmon spawn. Red line is recommended water temperature threshold for these locations for salmon spawning and egg incubation. Source: www.cbr.washington.edu/sacramento/

Figure 5. Threshold analysis for 2020 in upper Sacramento River. KWK=Keswick Dam. SAC=Redding. CCR=Above Clear Creek. BSF=Balls Ferry. JLF=Jelly’s Ferry. BND=Bend Bridge. Source

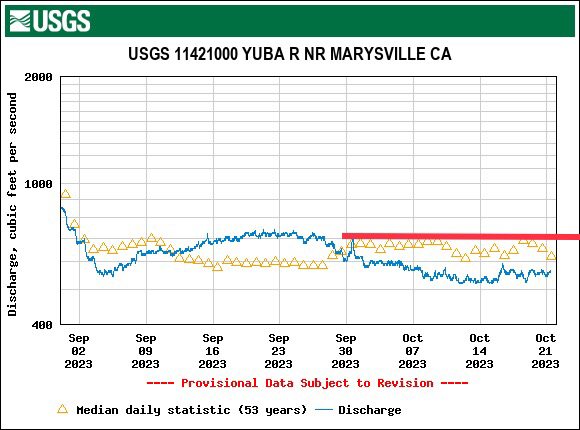

Figure 6. Lower Sacramento River flow rate September 2020 to March 2021.

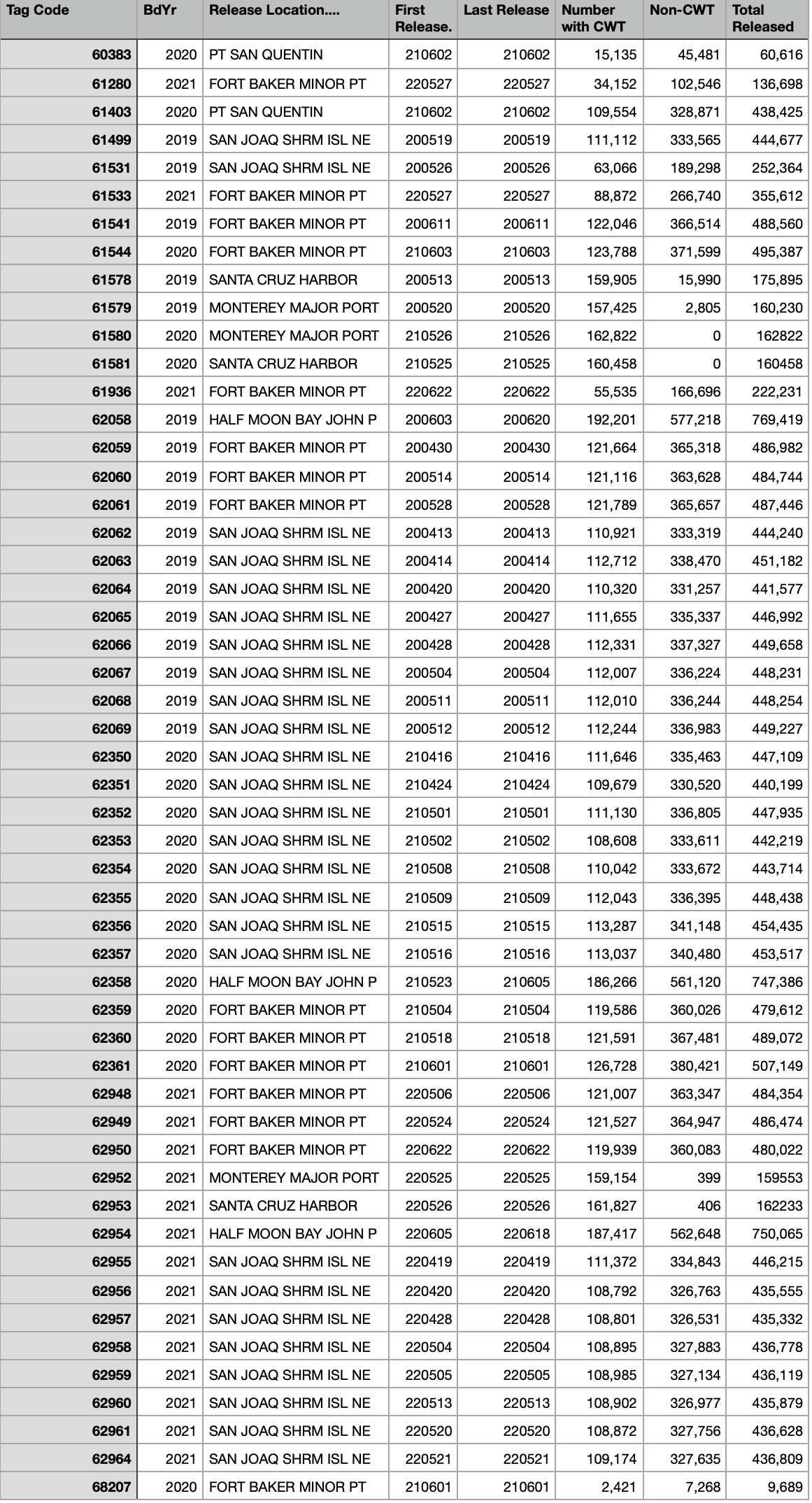

Figure 7. Broodyear index for winter-run salmon young catch at Knights Landing rotary screw trap 2008-2023. Source

Figure 8. Tisdale screw trap collections of winter run smolts in fall-winter of water year 2021. Source

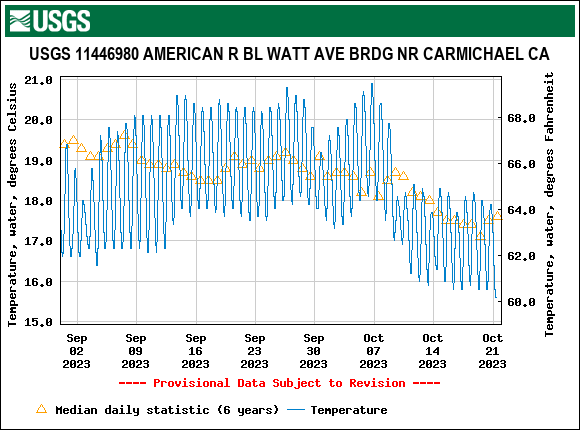

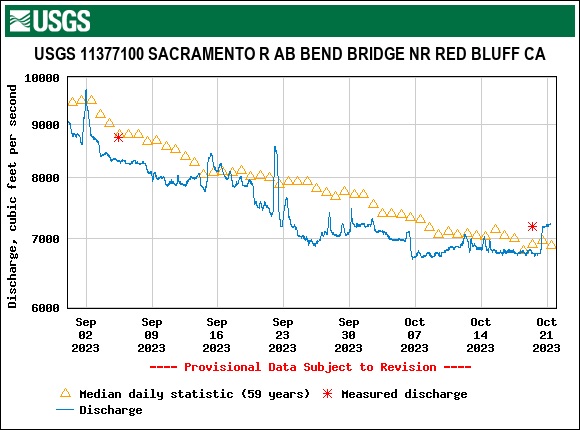

Figure 9. Water temperature in upper Sacramento River at Red Bluff and lower Sacramento River at Wilkins Slough April-July 2023. Red line is target threshold water temperature for winter-spring migrating adult salmon. Source

Figure 10. Water flow through three Sacramento Flood Control Weirs in 2023. TIS=Tisdale. CLW=Colusa. FRE=Fremont.

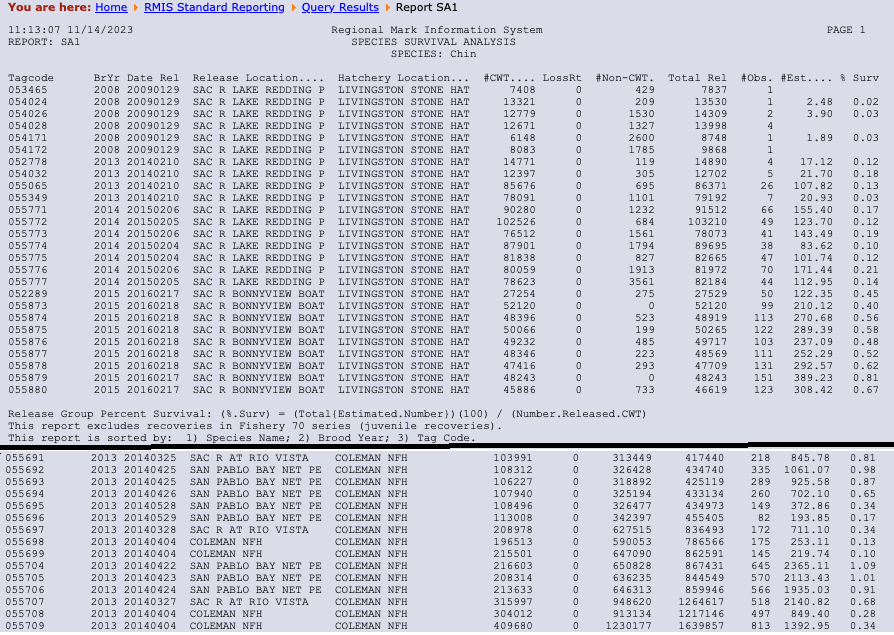

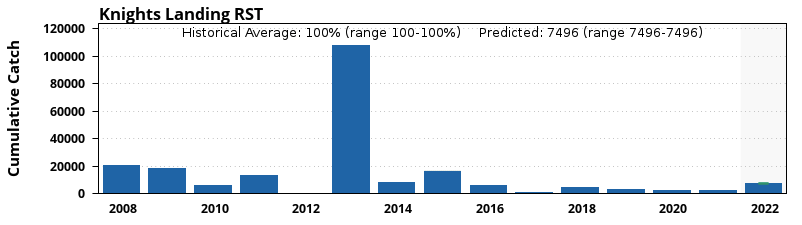

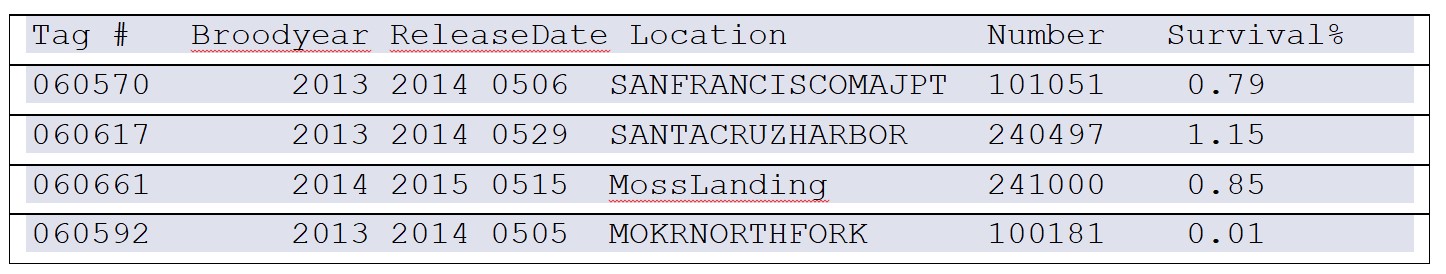

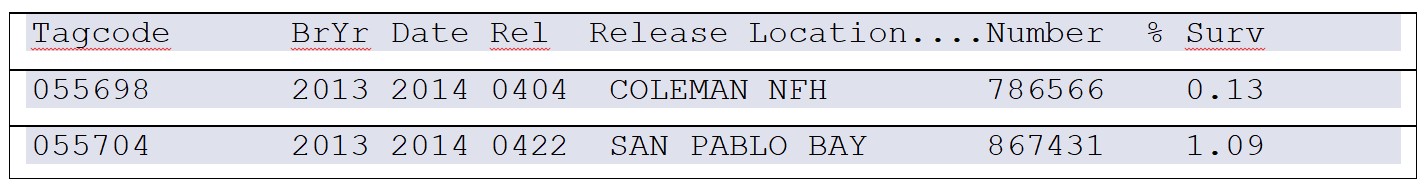

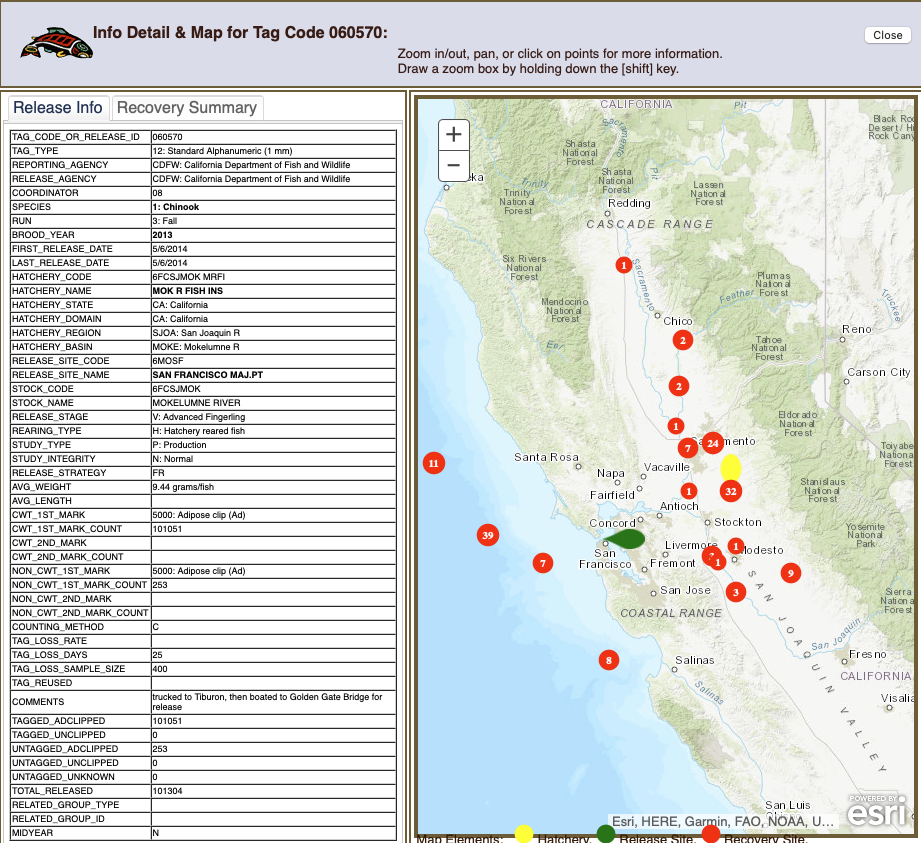

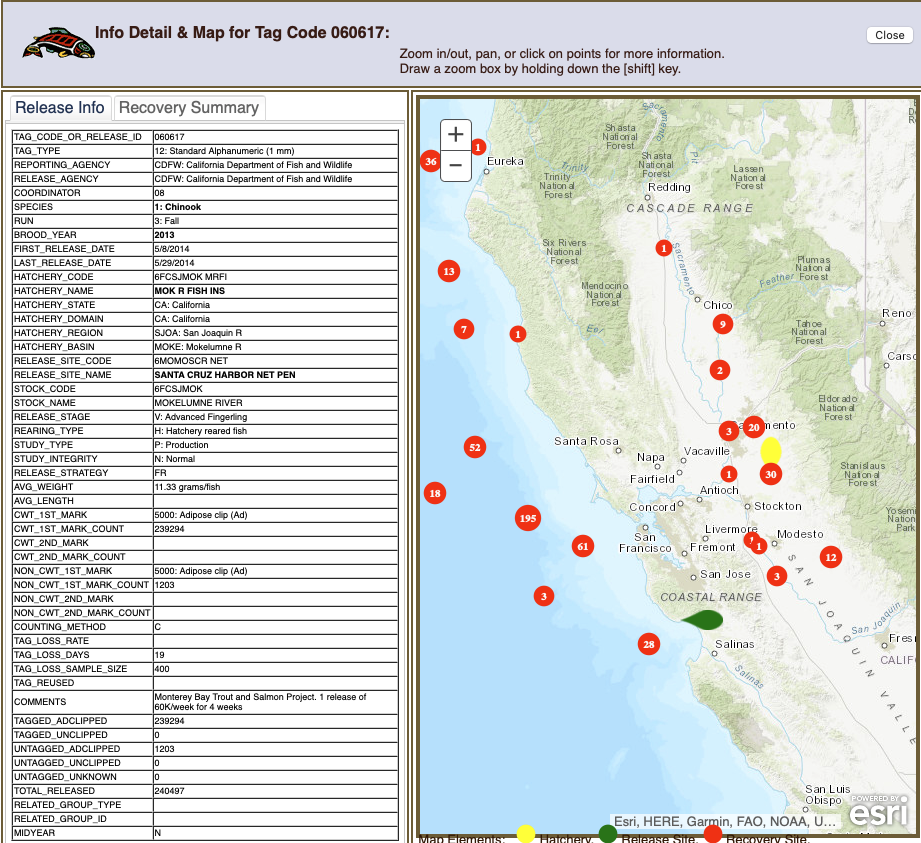

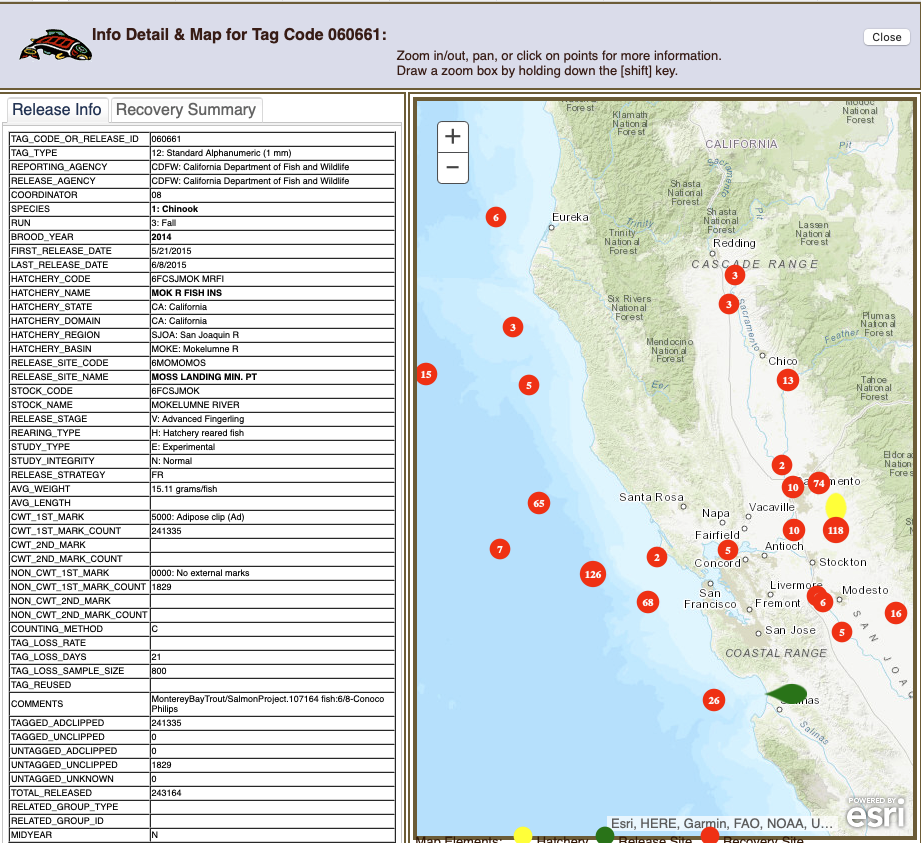

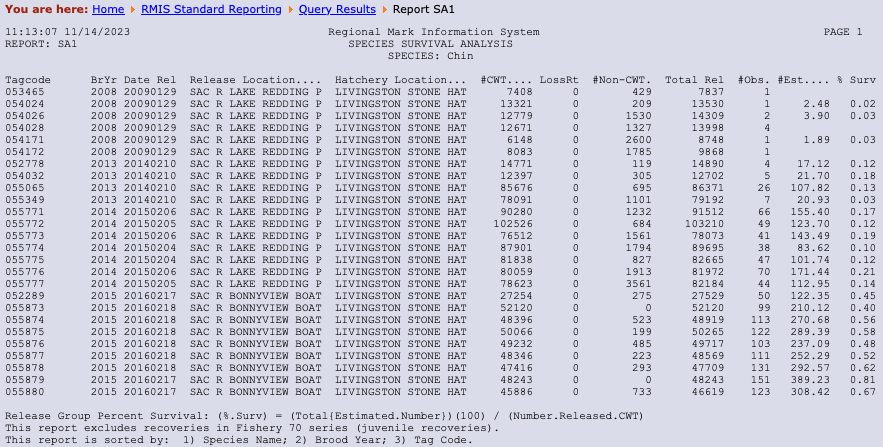

Table 1. Winter-run salmon hatchery releases percent survival for 2009, 2014, 2015, and 2016 release-year tag groups. Most returns occur at age three two years after release. Note low survival from 2009 releases (<0.03%), 2014 releases (0.03-0.18%), and 2015 releases (0.10-0.21%) in critical drought water years. Higher survival rates (0.40-0.81%) occurred from 2016 releases in a normal water year.