On March 2, CDFW reported the mortality of recently released (Feb. 28) salmon fry from the new Fall Creek Salmon Hatchery located on a Klamath River tributary upstream of the site of the recently removed Iron Gate Dam. The Iron Gate Hatchery located at the foot of the dam site was removed with the dam and replaced by the Fall Creek Hatchery. Mortality of the salmon fry was attributed to gas bubble disease caused by the fry passing through the Iron Gate Dam release tunnel.

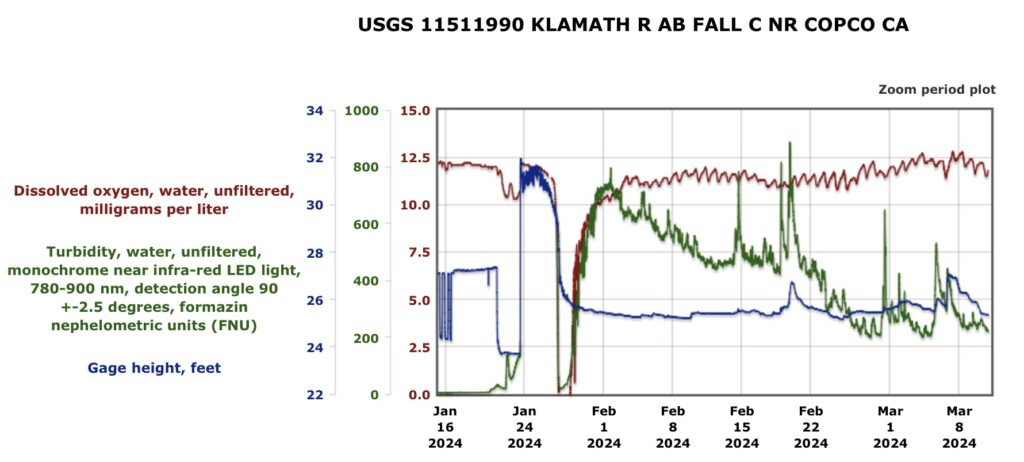

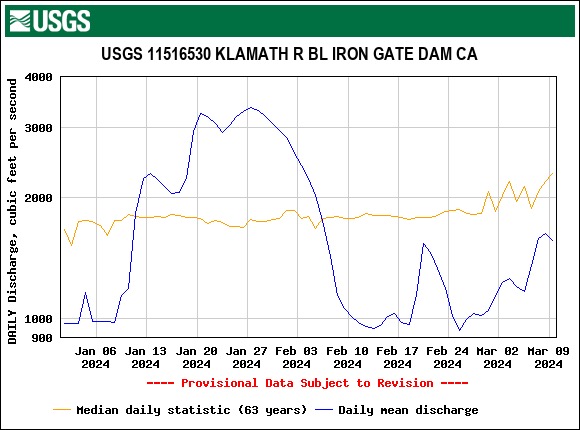

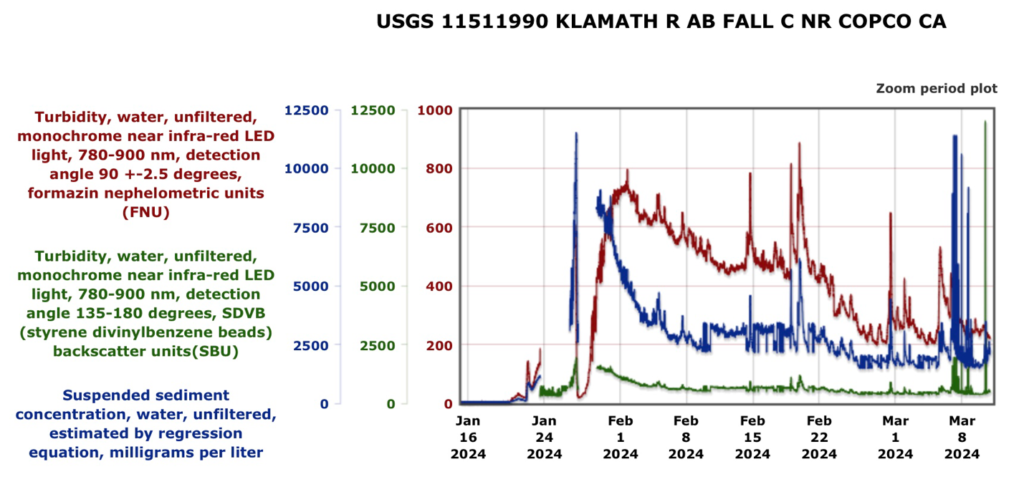

Iron Gate Reservoir and the three upstream reservoirs were emptied beginning on January 11 prior to dam removal. As the reservoirs were drained, the gage below Copco Dam picked up a large increase in turbidity with an associated complete loss of dissolved oxygen (Figure 1). Oxygen returned to the water after several days despite continued high turbidity. This indicated the initial dissolved oxygen loss was likely related to the flush of organic sediment from the bottom of the reservoirs as the draining neared completion. After the flows stabilized (Figure 2) and water level in the river had dropped six feet by the end of January, turbidity dropped and stabilized near 3000 mg/l suspended sediment, and normal high dissolved oxygen returned. Turbidity was measured using three parameters (Figure 3).

The hatchery salmon fry released on February 28 were subjected to a Klamath River with elevated turbidity (suspended sediment concentrations above 2000 mg/l). Such concentrations for extended exposure (days) are highly detrimental to salmon fry.1 The combination of high suspended sediment and gas bubble disease likely has contributed to poor juvenile salmon production this year in the lower Klamath River.

The removal of the Klamath River dams will have substantial long-term benefits for salmonids. As the dam removal process proceeds, it is important to mitigate the short-term impacts of high turbidity levels to the degree possible. Continuing high turbidity events (see March levels in Figure 3) do not bode well for hatchery or wild salmon in the Klamath this year. With nearly 4 million juvenile Chinook salmon yet to be released from the Fall Creek Hatchery this year, it would be wise to either wait for next fall to release them or truck the smolts to the Klamath estuary.

Figure 1. Water level, suspended sediment, and dissolved oxygen in the Klamath River above Iron Gate Reservoir and mouth of Fall Creek, January 16 to March 10, 2024.

Figure 2. Streamflow below the Iron Gate Dam site January 1 to March 10, 2024. Source: USGS.

Figure 3. Suspended sediment and turbidity upstream of Iron Gate Reservoir above the mouth of Fall Creek near Copco, January 16 to March 10, 2024.

- Newcombe, C.P., and J.O.T. Jensen. 1996. Channel suspended sediment and fisheries: a synthesis for quantitative assessment of risk and impact. North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 16:693-727. ↩