A September 2018 Bureau of Reclamation “fact sheet” on raising Shasta Dam is misleading.

Enlarging the reservoir will provide an additional 630,000 acre-feet of stored water for the environment and for water users.

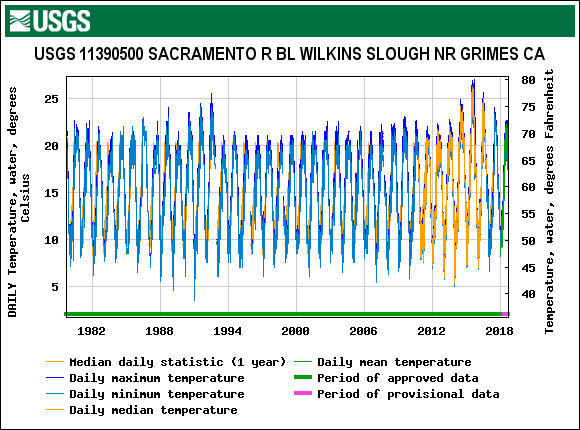

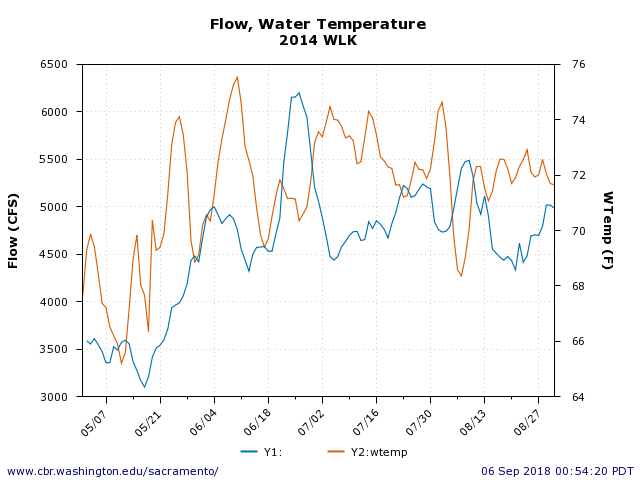

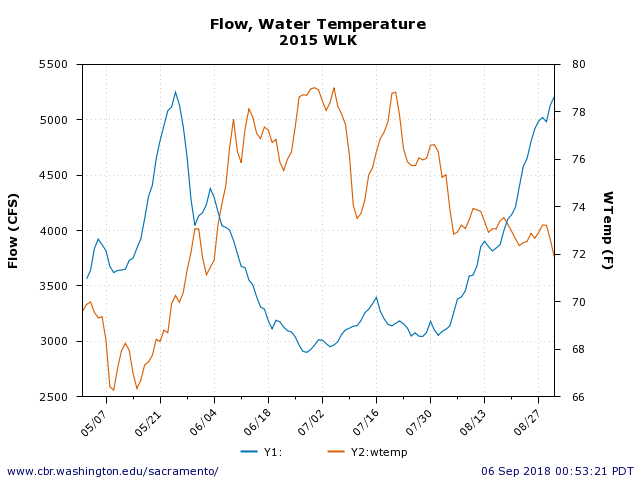

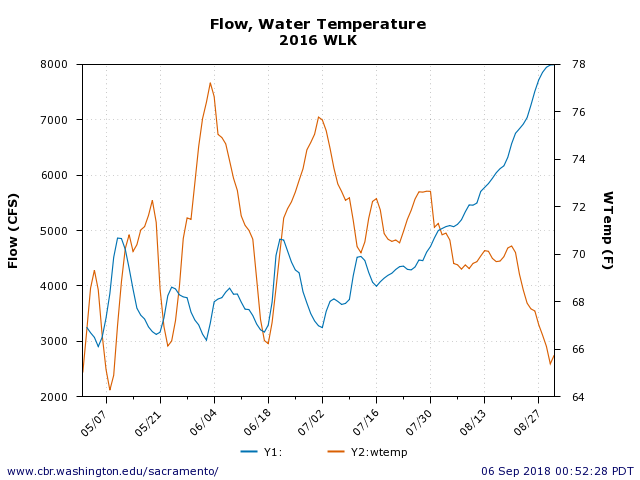

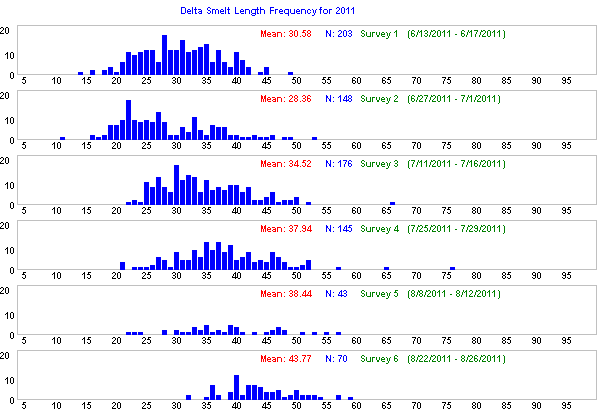

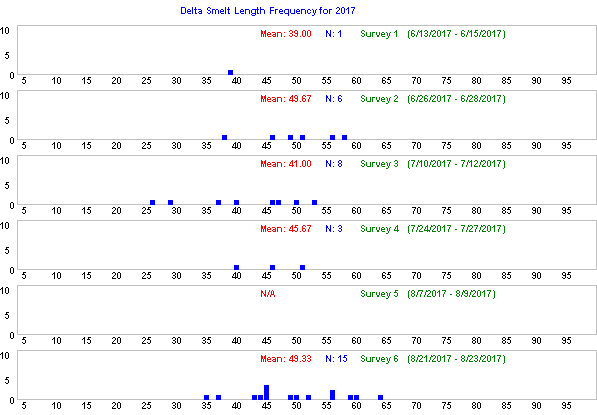

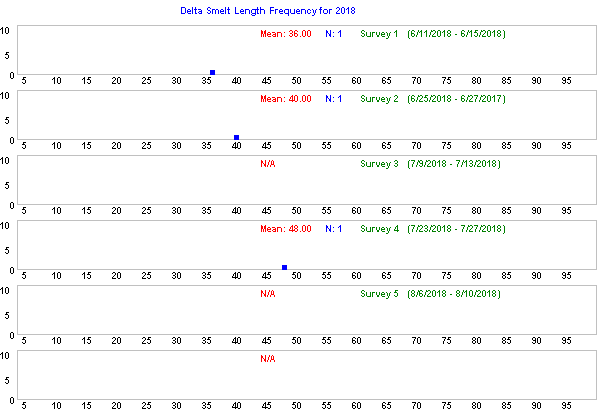

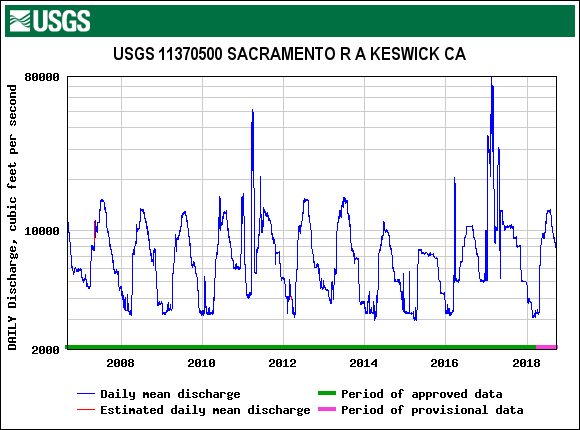

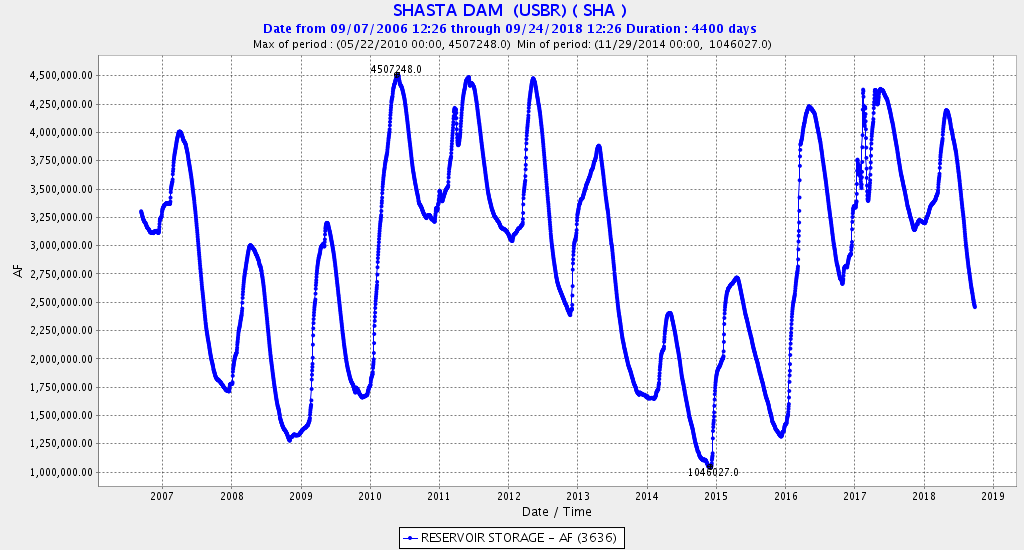

Comment: Additional storage would have been accomplished in only two years of the last decade (Figure 1). There would have been no additional cold-water pool volume in critical years 2013-2015, when the loss of cold water was a problem (Figure 2). Water users already had 100% allocations in the years in which raising Shasta would have added storage. Water allocations would likely increase in some dry years following wet years, offsetting any prospective environmental benefit by drawing down storage.

Enlarging the reservoir will improve water supply reliability for agricultural, municipal and industrial, and environmental uses; reduce flood damage; and improve water temperatures and water quality in the Sacramento River below the dam for anadromous fish survival.

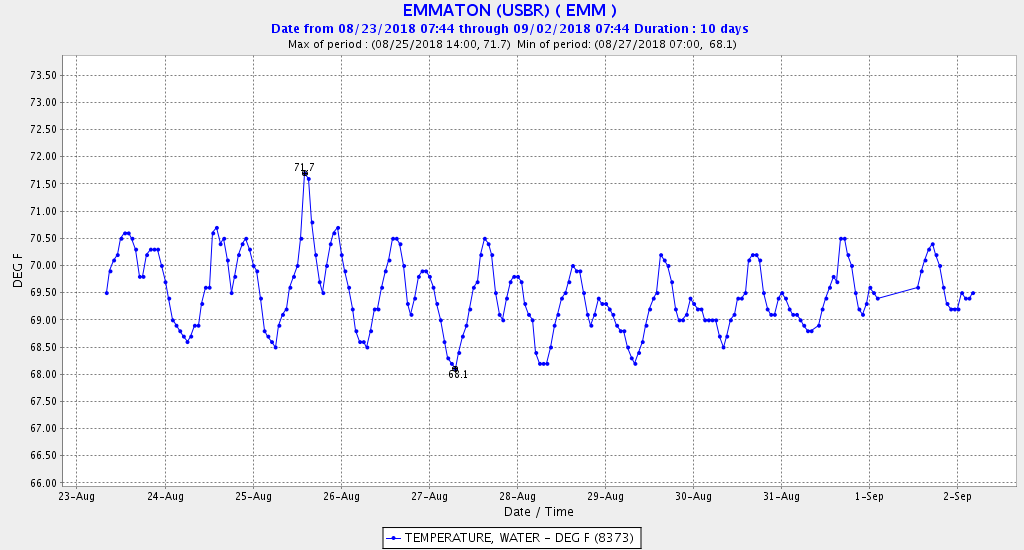

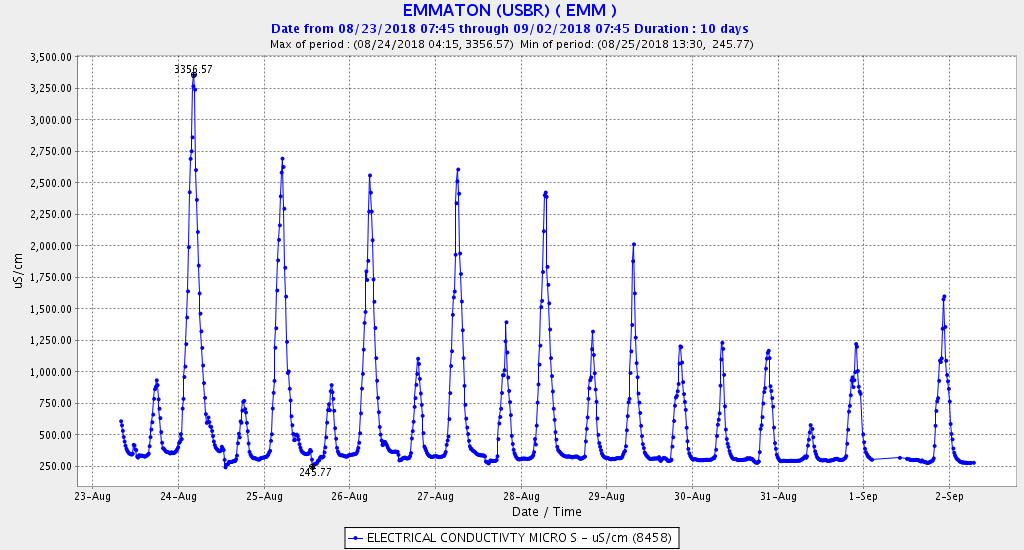

Comment: there would have been no flood benefits in the past decade. Critical-year water temperatures from 2013-2015 would not have changed. Sacramento River water quality suffers the most in critical drought years. This would not benefit from raising Shasta.

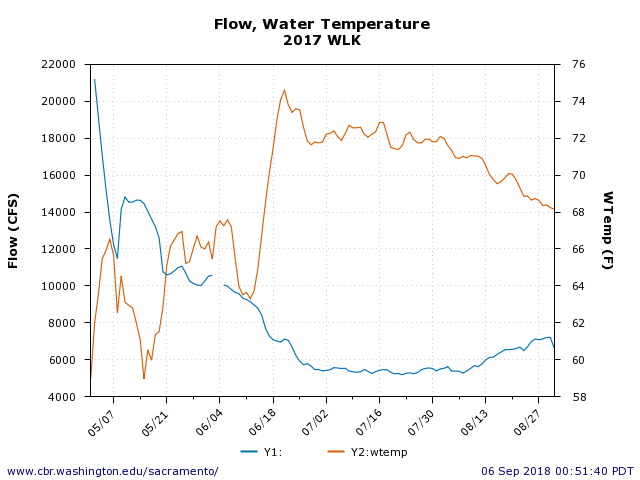

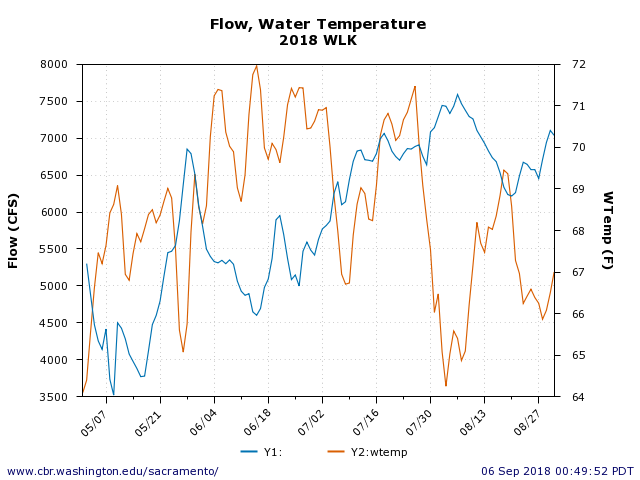

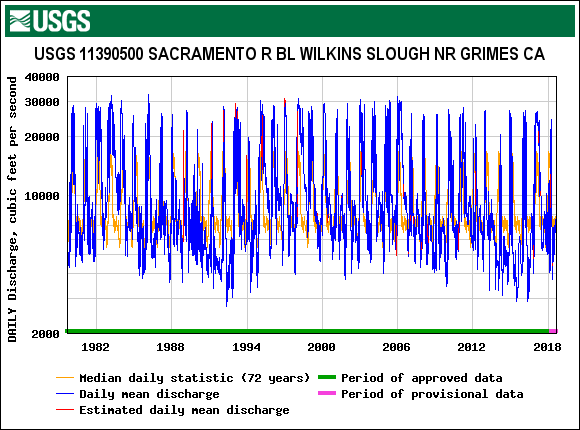

Figure 1. Daily average flows from Keswick Reservoir over past decade. Raised Shasta would only accommodate added storage in wet year spill events in water years 2011 and 2017.

Figure 2. Shasta storage volume over past decade. Maximum existing storage is 4,552,000 AF.