“While state and federal wildlife agencies, university researchers, and water users all agree that predation from non-native fishes is a major stressor on salmon populations, we have done nothing to try to directly curb its impact.”

This statement in a recent Fishbio blog post is simply not true.

In 1995, the state removed limits on summer Delta exports that had been in place for decades to protect young striped bass. Stocking of striped bass ended at the beginning of this century. Both actions contributed to record low production of striped bass over the past decade. 1 The Bay-Delta population of striped bass is now greatly depressed. The river population is sustained by the continuing policy of releasing hatchery salmon smolts in the spring at the hatcheries, an unnatural process that simply feeds the river stripers.2

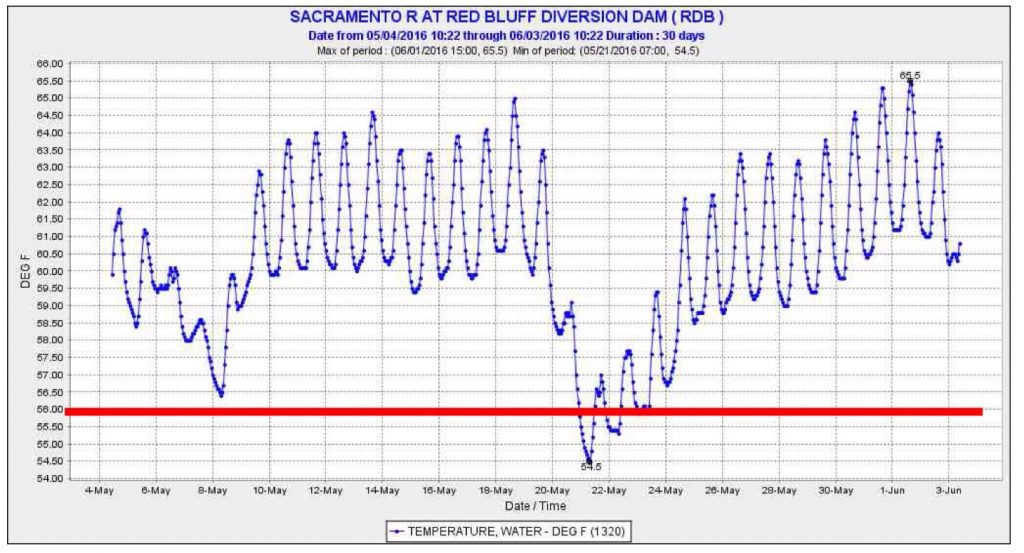

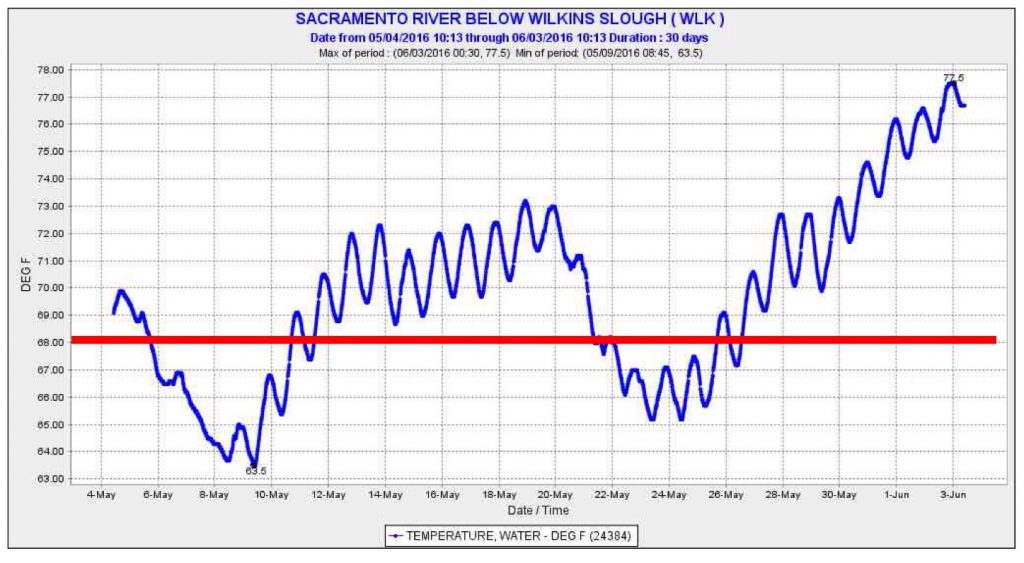

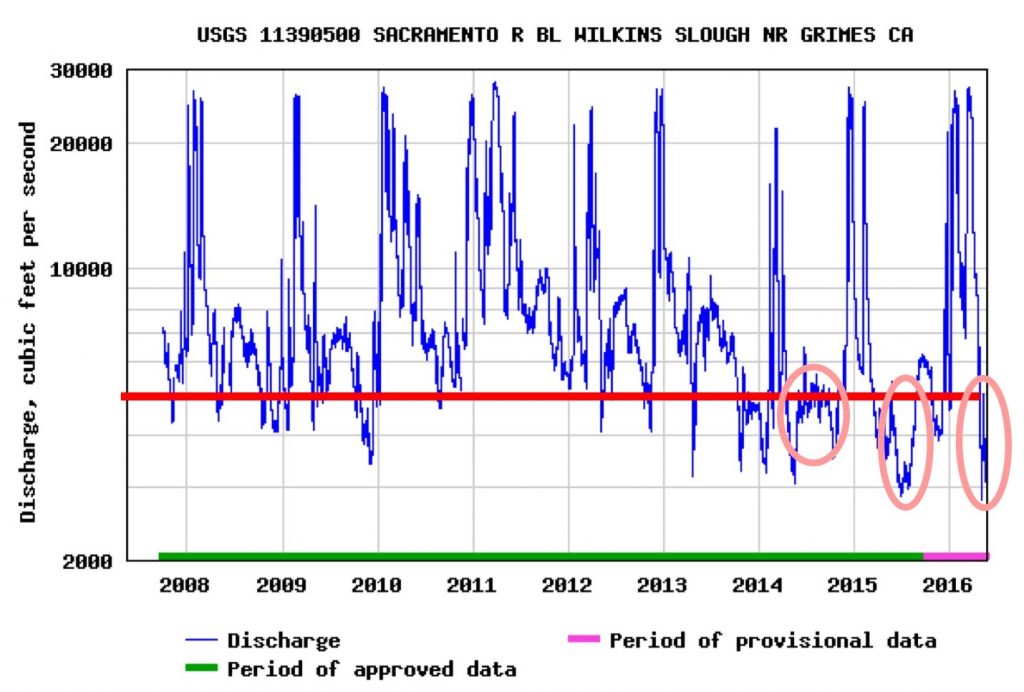

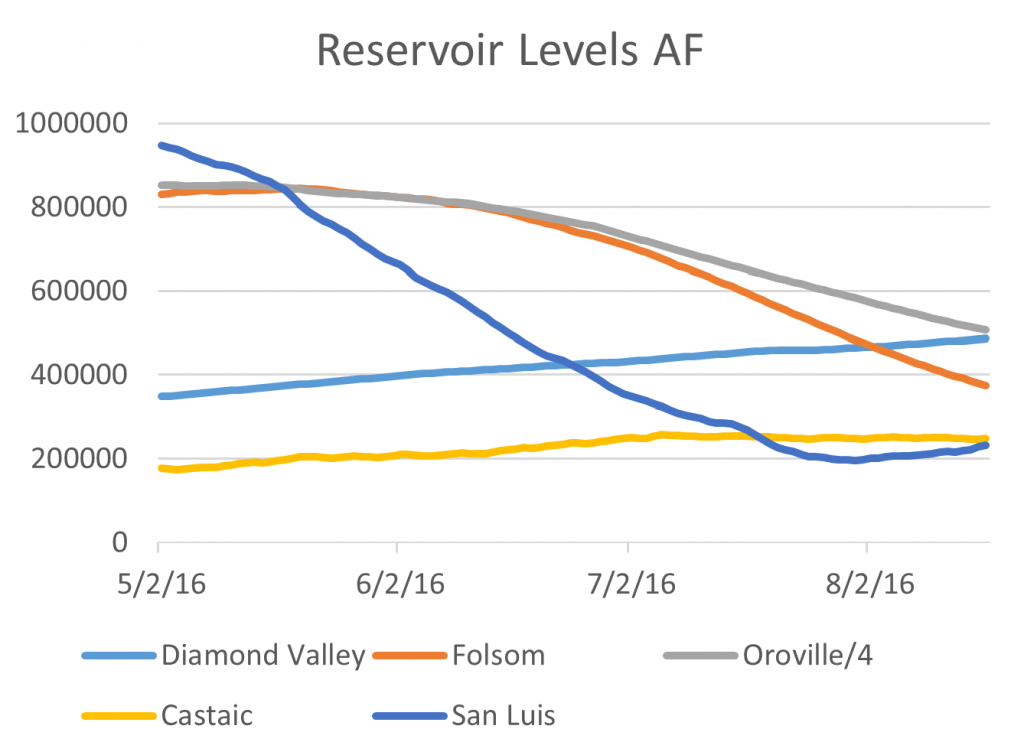

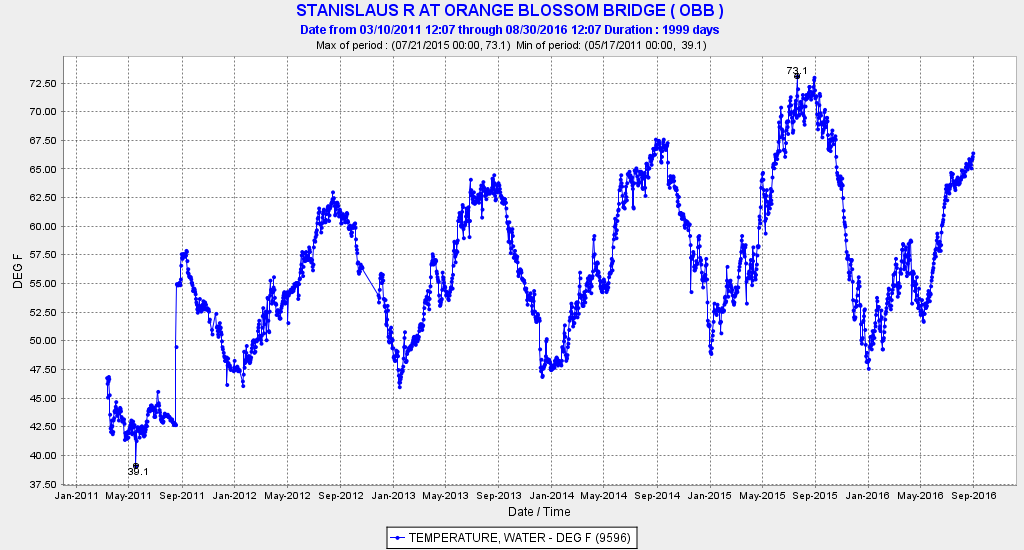

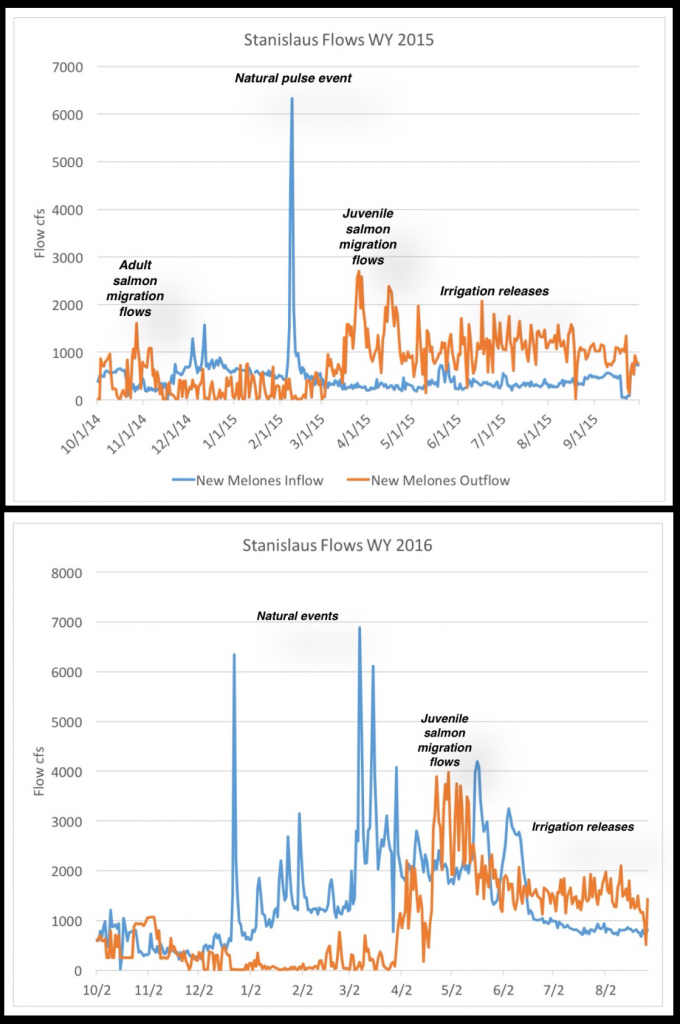

The real problem is spring water management in the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers that brings unnaturally low flows and warm, clear water that favors the predators. All the salmon runs naturally have juveniles migrating to the Bay in high cold flows from late fall to early spring when predators are inactive and ineffective. But with dams holding the water from winter rains and snows, the rivers lack natural winter flows and spring snowmelt.

Largemouth bass production in the Delta has increased because of habitat changes from water management, droughts, and invasive aquatic plants that have turned the Delta into an “Arkansas lake.” Smallmouth bass production has increased in the rivers with lower, warmer flow conditions from spring through fall.3

The native pikeminnow also benefit from the habitat changes in the rivers and Delta, as well as the abundance of spring hatchery smolts. Huge schools migrate from the Delta into the rivers in spring and summer to spawn. The tailwaters downstream of dams favor pikeminnow. The adults feed on young salmonids and the juveniles compete with juvenile salmonids. Juvenile pikeminnow that return to the Delta feed on smelt.

It is these habitat changes that have resulted in more effective predation on native salmon, steelhead, and smelts. Ignoring the cause won’t solve the problem. Focusing on the predators will not work. The basses and native pikeminnow have prolific reproductive systems. Killing more of them by removing regulations on their harvest or even putting bounties on them (like pikeminnow on the Columbia River) will not solve the root problem – habitat change. And without the predators, what would be left to control all the non-native forage and “trash-fish” that already plague the Delta and rivers?

In the future, if we continue to take more of the river flows and further degrade habitats, there will always be the temptation and the drumbeat to directly remove predators or inhibit their migrations. We can stop salvaging millions of these predators every year at the South Delta export facilities, stop returning all the bass caught in fishing tournaments, and truck all the remaining salmon produced only in hatcheries to the Bay. In the end we will still have abundant predators, an “Arkansas-like lake,” hatchery salmon, and at best novelty populations of endangered wild salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, smelts, complemented by likely newly listed species of native fishes like splittail, blackfish, hitch, etc.