In a 10/19/2023 post and a 11/21/2024 post, I discussed how the lack of access to Folsom Reservoir’s deep cold-water pool results in delayed natural and hatchery spawning of American River fall-run salmon. Delays, and spawning in warmer water, cause reductions in spawning success, smolt production, recruitment into harvestable fishery stocks, and spawning escapement (run size) to the American River. Lower salmon contributions from the American River significantly reduce California coastal and river salmon fishery stocks. Poor production in the American River contributed to the closure of California salmon fisheries in 2023-2025.

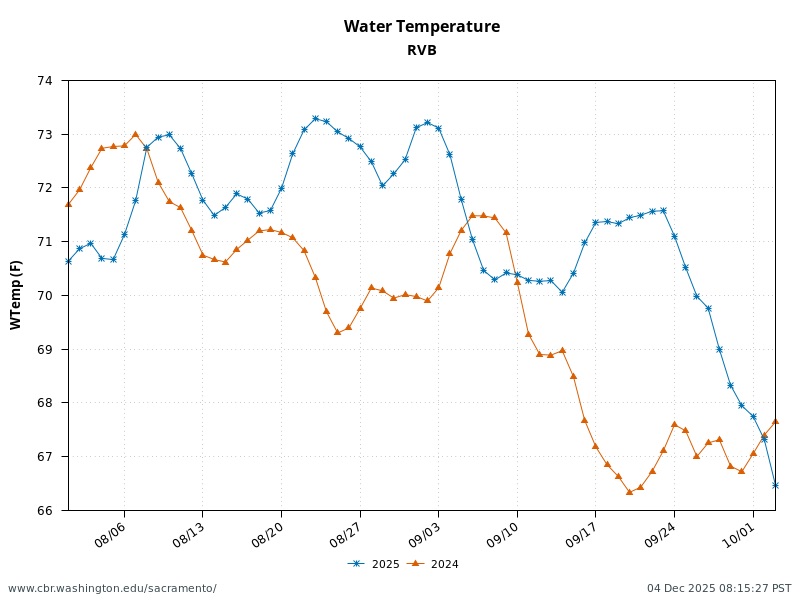

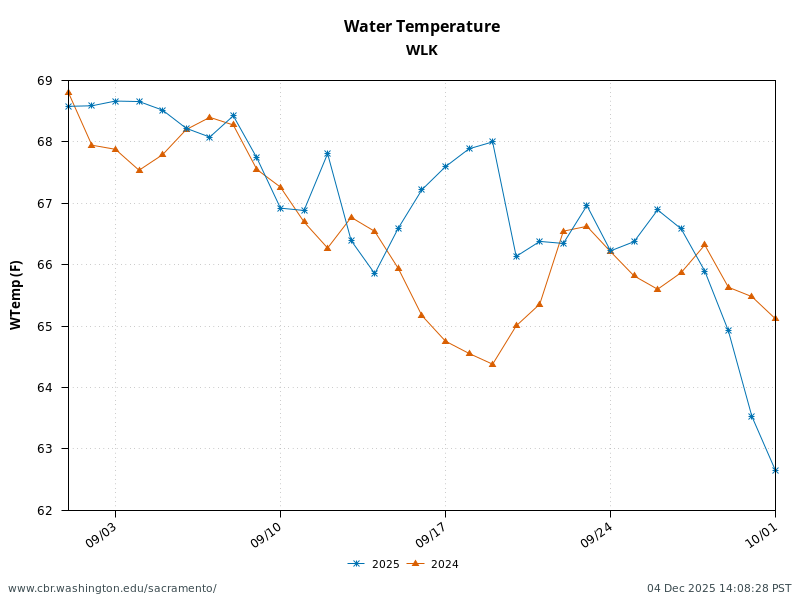

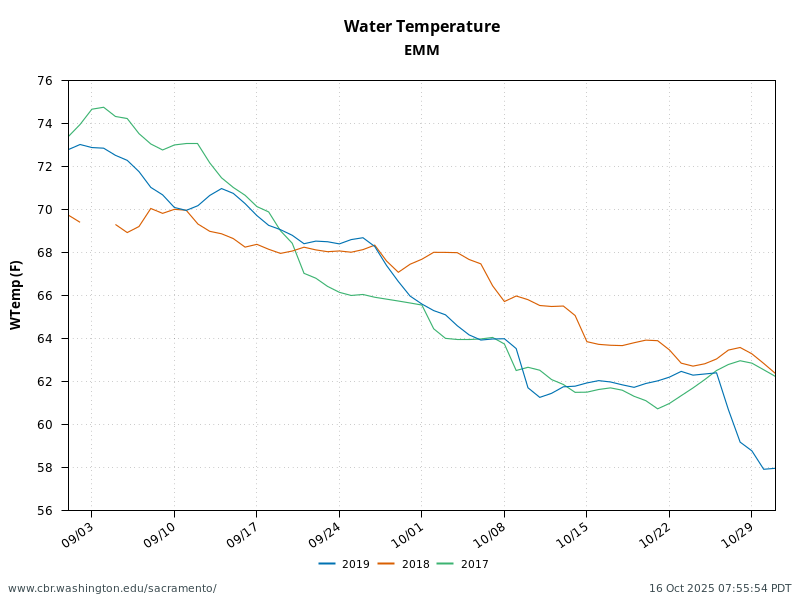

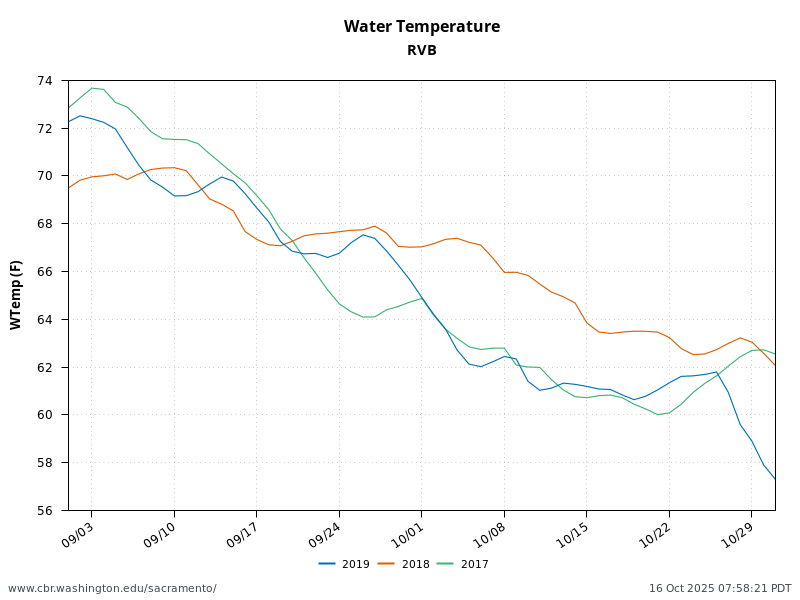

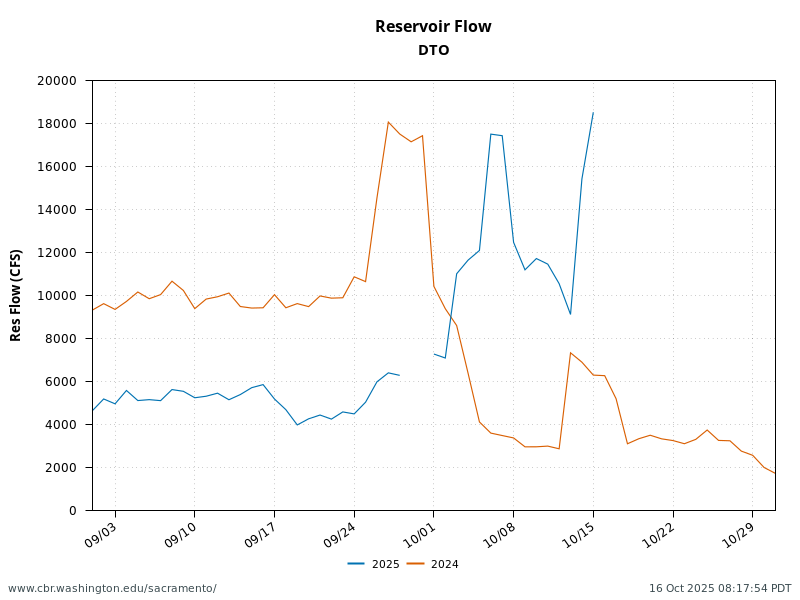

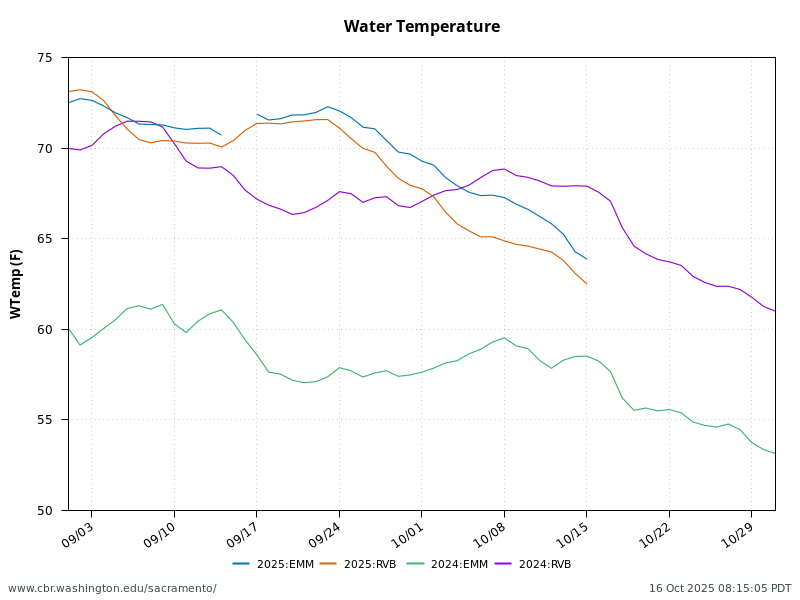

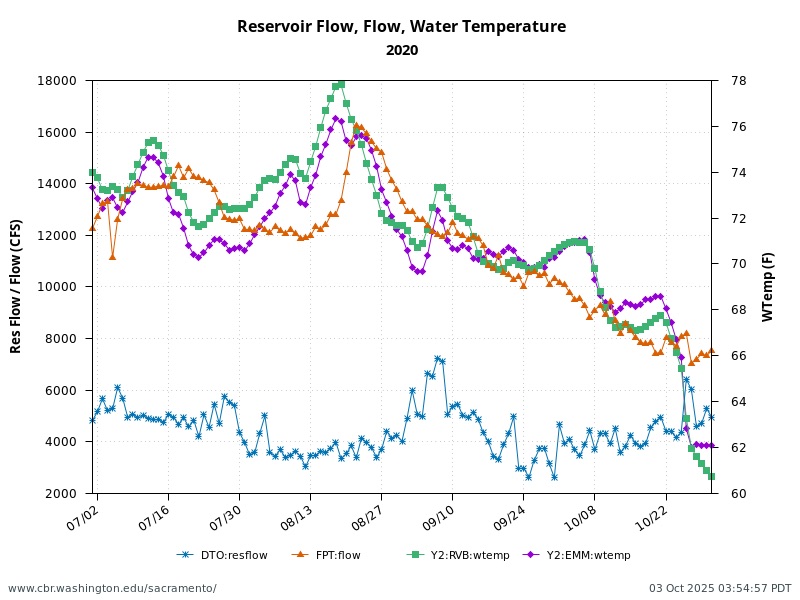

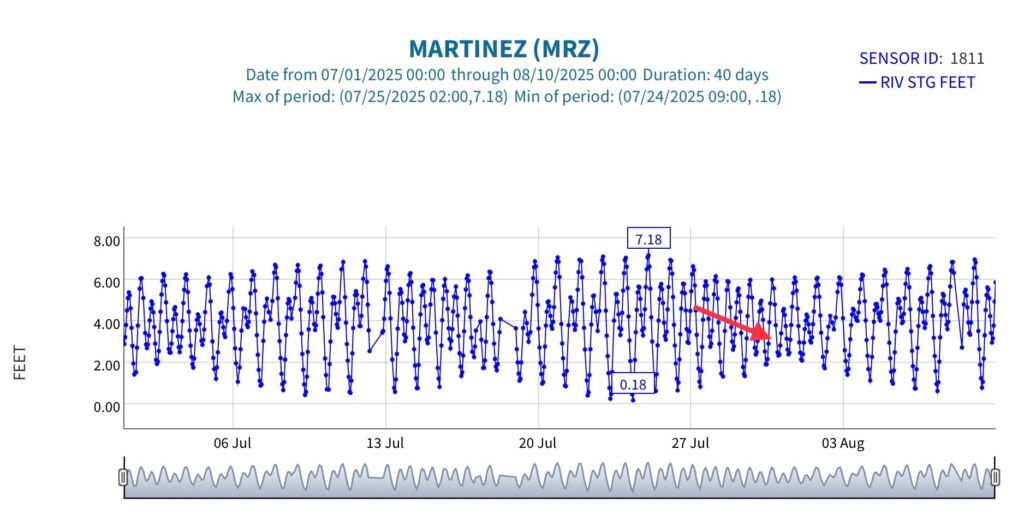

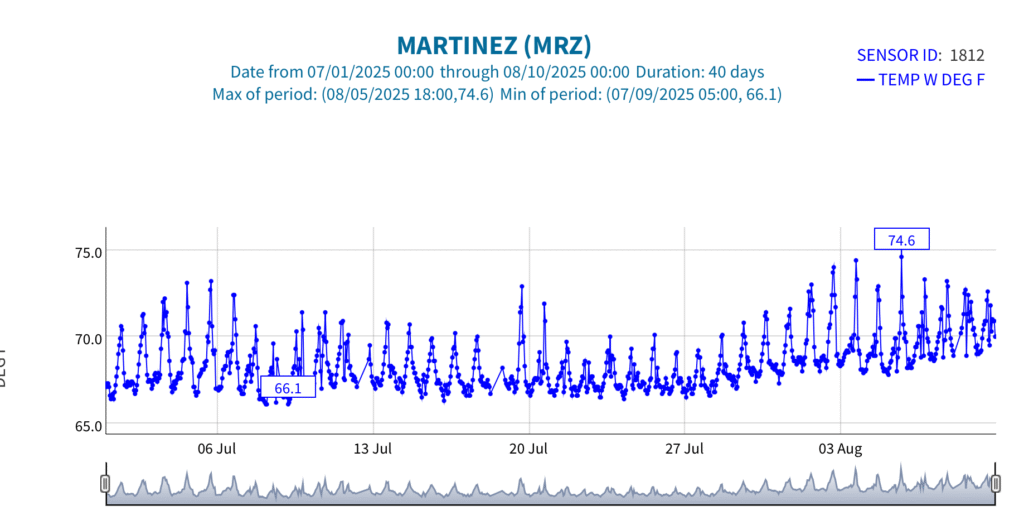

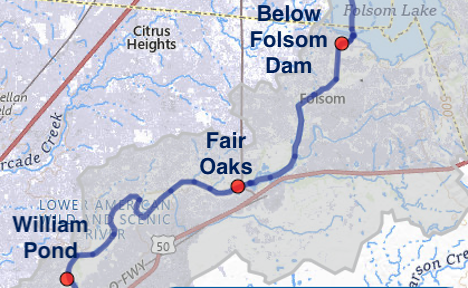

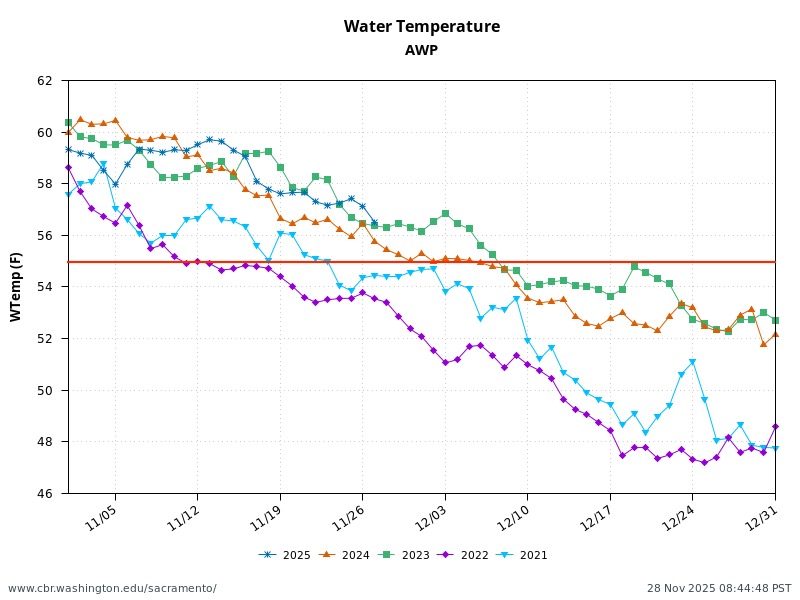

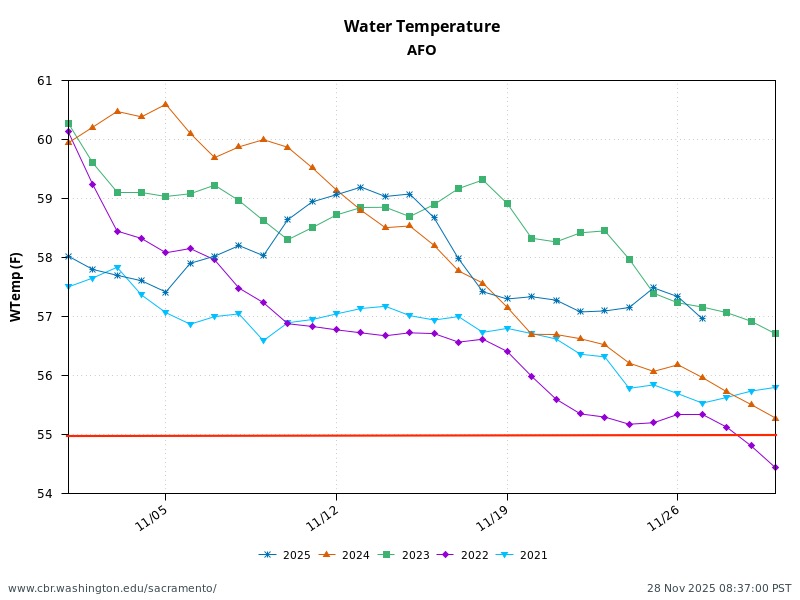

During the 2020-2022 drought, Reclamation released water from the lower-level power bypass (sacrificing hydropower production) to provide the cold water (<55ºF) salmon needed for spawning in the ten-mile spawning reach from Nimbus Dam (near Fair Oaks gage) to the William Pond gage (Figure 1). This is the prime spawning reach for salmon in the lower American River. However, in the fall of the wetter years 2023-2025, Reclamation did not use the power bypass to release cold water (Figures 2 and 3), despite higher storage levels than during the drought (Figure 4). The lack of cold water delayed natural spawning and hatchery egg taking, to the detriment of egg viability, fry production, and smolts reaching the ocean.

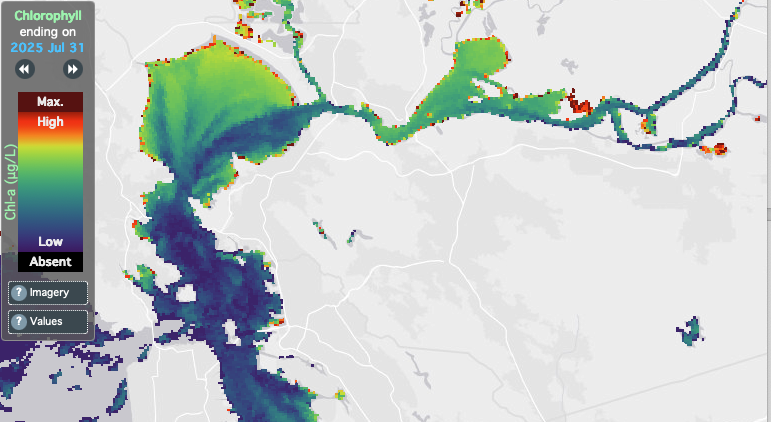

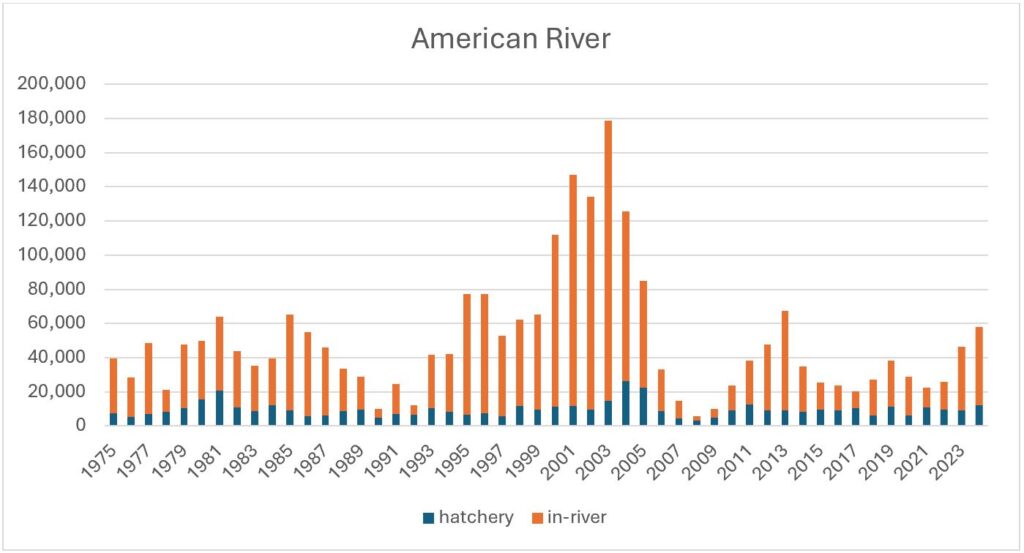

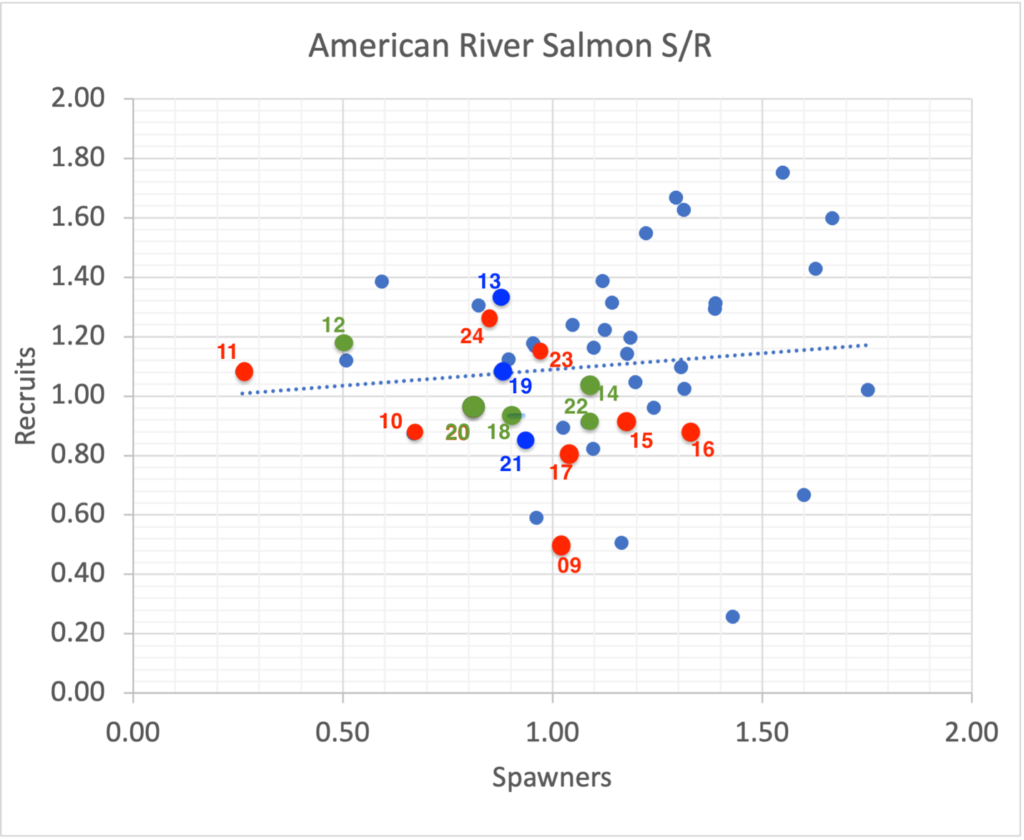

Ultimately, the number of adult salmon returning to the American River to spawn (escapement) is the important measure of success. There are many factors that may contribute to the number of returns. Recent returns are up (Figure 5). The 2023 and 2024 returns were good despite having been the product of the 2020-2022 drought reproduction (Figurer 6). Closed fisheries in 2023 and 2024 contributed to higher escapements.

I also believe efforts to improve fall water temperatures below Folsom during the drought improved both the wild and hatchery components of escapement. I remain concerned that a return to warmer fall water temperatures will hinder future escapement.

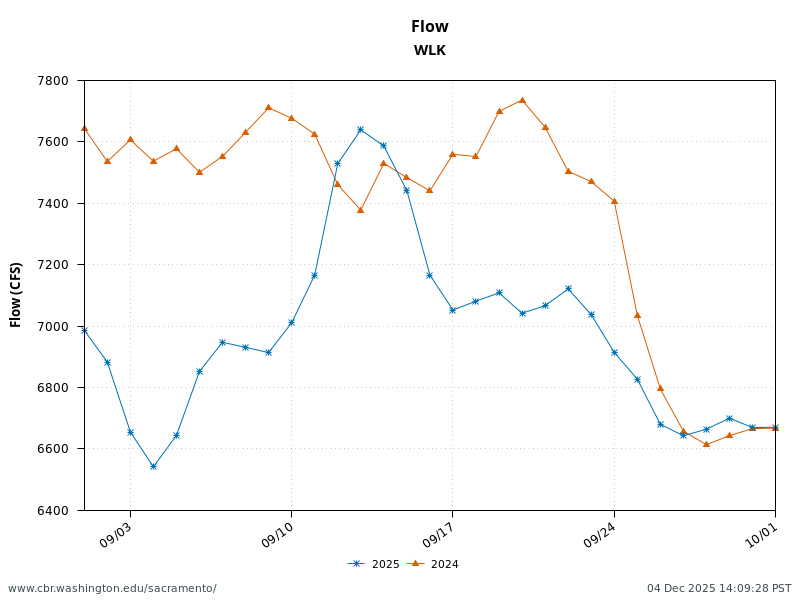

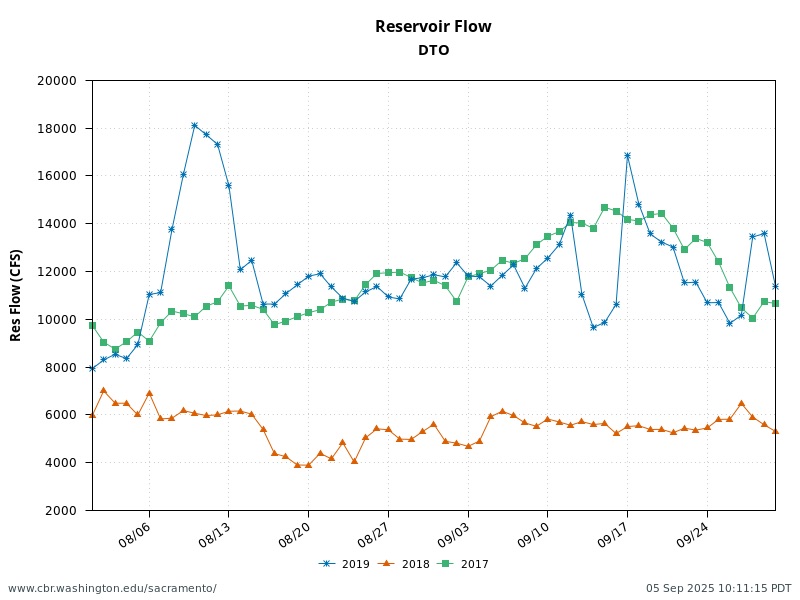

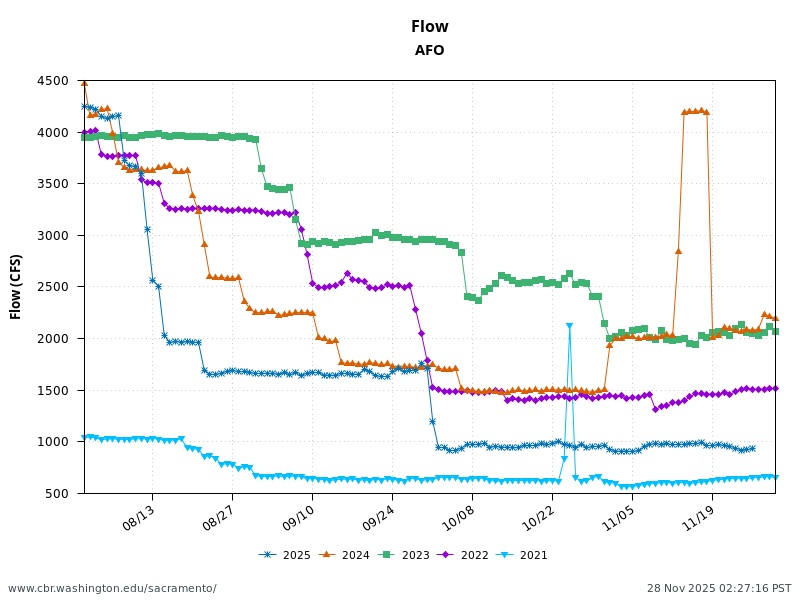

I am also concerned with apparent efforts to sustain higher fall 2025 reservoir levels (see Figure 4) by reducing tailwater stream flow rates (Figure 7). Such low flows reduce the quantity and quality of salmon spawning habitat. Many critical spawning side channels become dewatered at such low flows1. Main channel velocities, substrate, and depths are also compromised at low flow rates.

Reclamation also reduced funding for the salmon hatchery and for river habitat projects in 2025, and will likely do the same in subsequent years. This strategy will not help to recover American River salmon stocks to levels that once again can contribute toward commercial and recreational salmon fisheries.

Figure 1. Map of three CDEC gaging stations on the lower American River.

Figure 2. Average daily water temperatures in Nov-Dec period at William Pond gage 2021-2025. Red line (55ºF) denotes upper safe level for Chinook spawning.

Figure 3. Average daily water temperatures in November period at Fair Oaks gage 2021-2025. Red line (55ºF) denotes upper safe level for Chinook spawning.

Figure 4. Late summer and fall Folsom Reservoir water storage (acre-feet) 2021-2025.

Figure 5. Adult salmon escapement estimates for the American River 1975-2024. Source: Grand Tab.

Figure 6. American River spawner/recruit relationship – { log10(escapement) -3.5]. Number is year of escapement (recruits). Color denotes water year type two years prior. Red is dry, green is normal, and blue is wet. Note escapement in 2023 and 2024 are red, denoting spawning and rearing occurred two years earlier in dry water years.

Figure 7. Streamflow (daily average) in the American River at Fair Oaks gage Aug-Nov period 2021-2025.