Dan Bacher’s report on 2018 salmon returns to the Mokelumne River Hatchery provides continuing good news for the Mokelumne River salmon run.

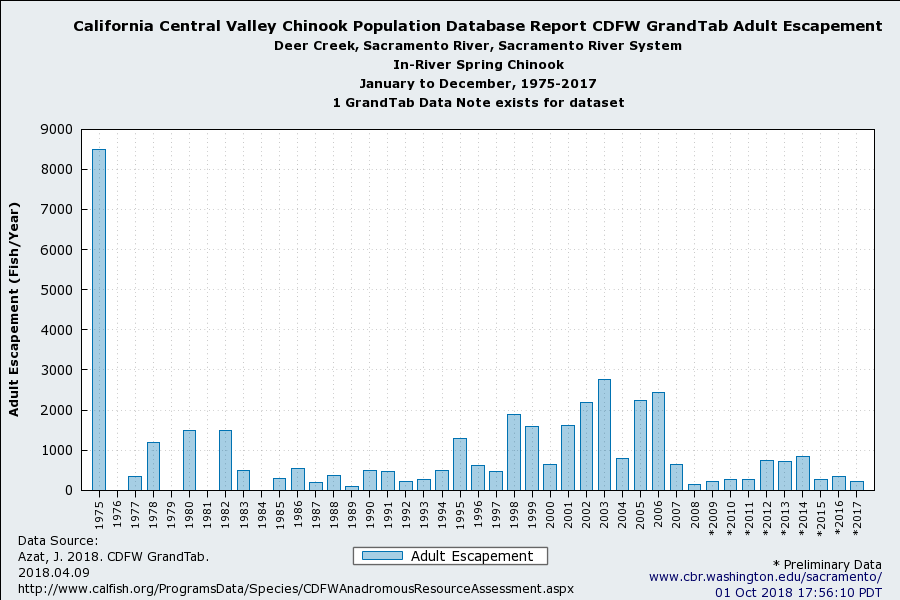

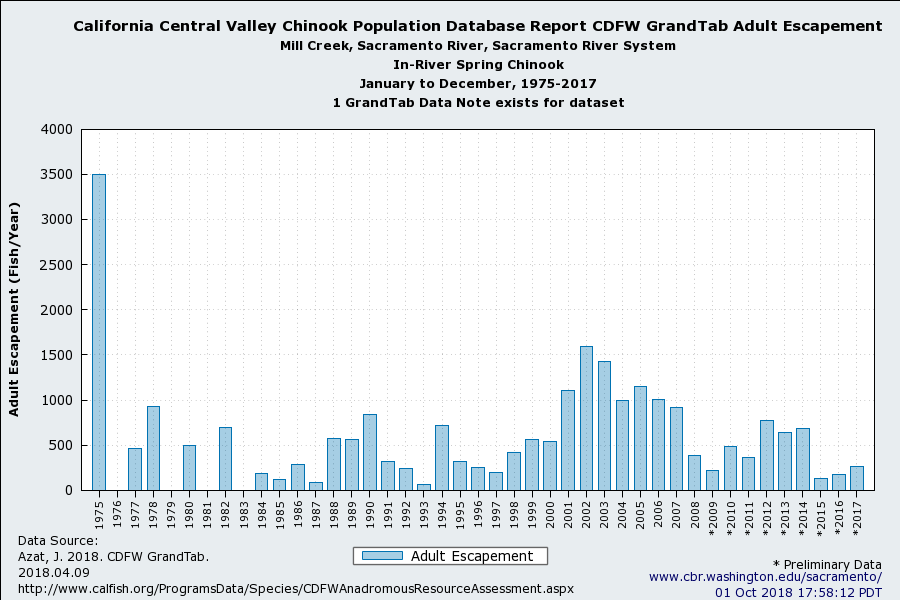

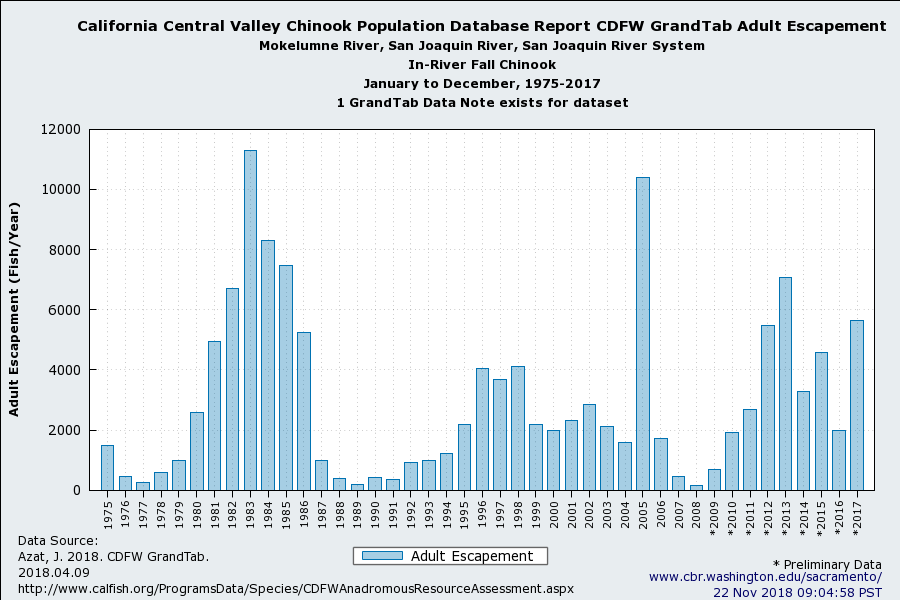

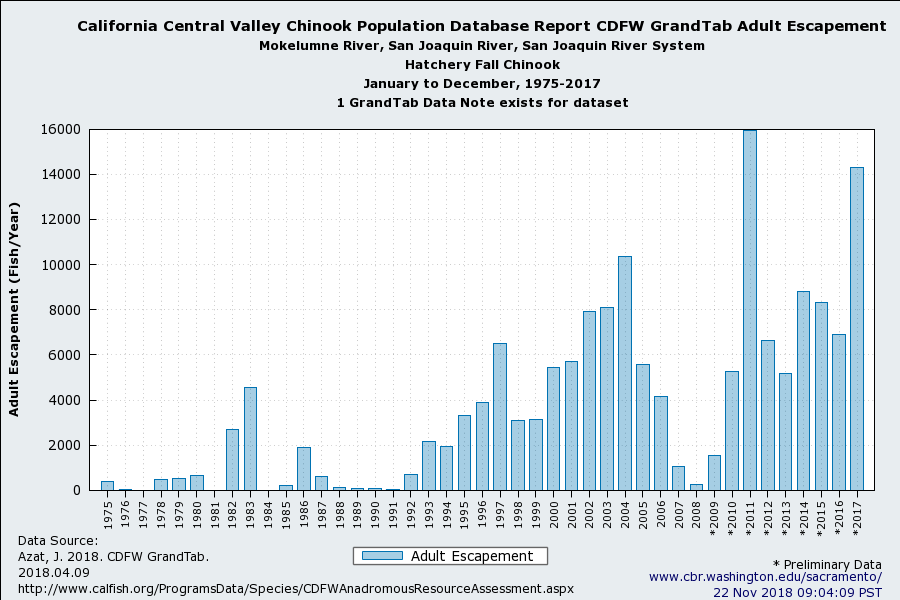

When I last reported on the fall run of Mokelumne River salmon, I described strong runs from 2010-2016. The 2017 run was exceptionally strong (Figures 1 and 2), despite being the product of the 2013-2015 drought. This success story is in large part due to the management of the Mokelumne River Hatchery, as reported in the Bacher article. Trucking hatchery smolts to the lower San Joaquin in the western Delta near Jersey Point greatly improves survival over releases of salmon in the lower Mokelumne River.

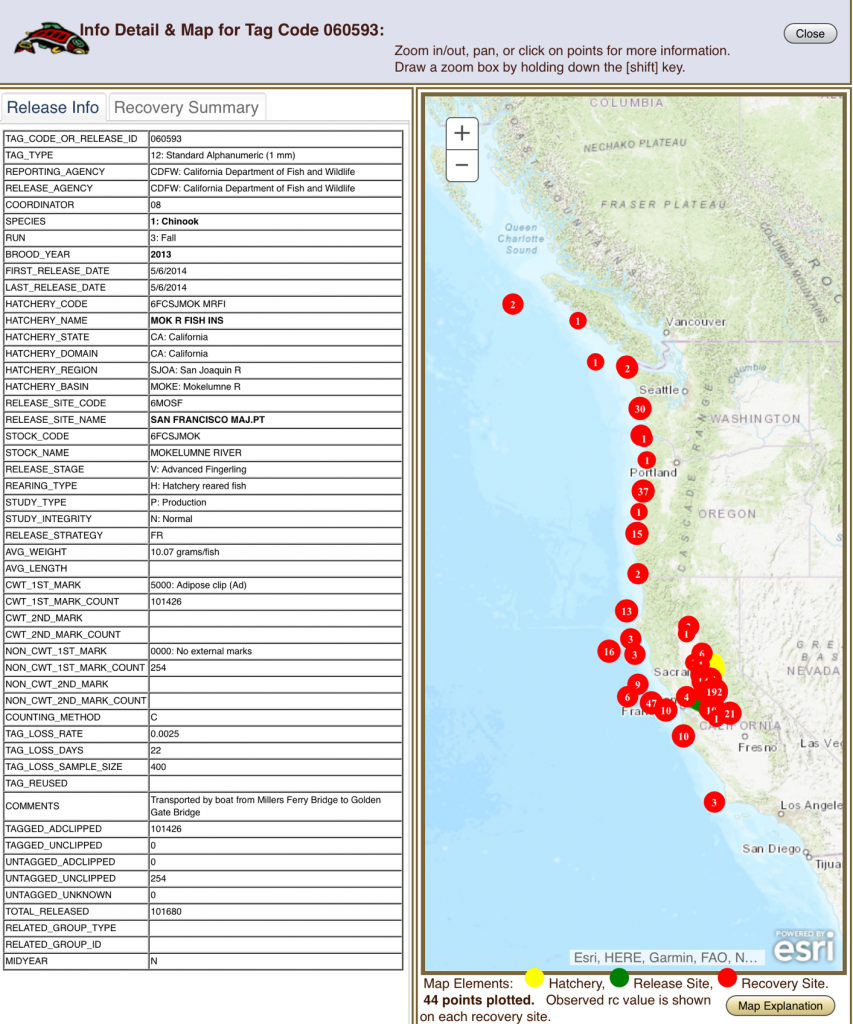

Best returns from the spring 2015 releases were from smolts barged and released near the Golden Gate. That group of 101,000 smolts (tag code #060593) had a good return of 1.35 percent compared to 0.06-0.80 % from smolts released in the west Delta and 0.01 % released in the lower Mokelumne River. In early May 2015, soon after river and Delta smolt releases, water temperatures reached 68oF in the west Delta and 72oF in the lower Mokelumne in the central Delta, levels stressful to smolt salmon. Delta outflow in early May 2015 was critically low at ~5000 cfs. Net flow in the lower San Joaquin River in the west Delta, with the Delta Cross Channel closed, was near zero.

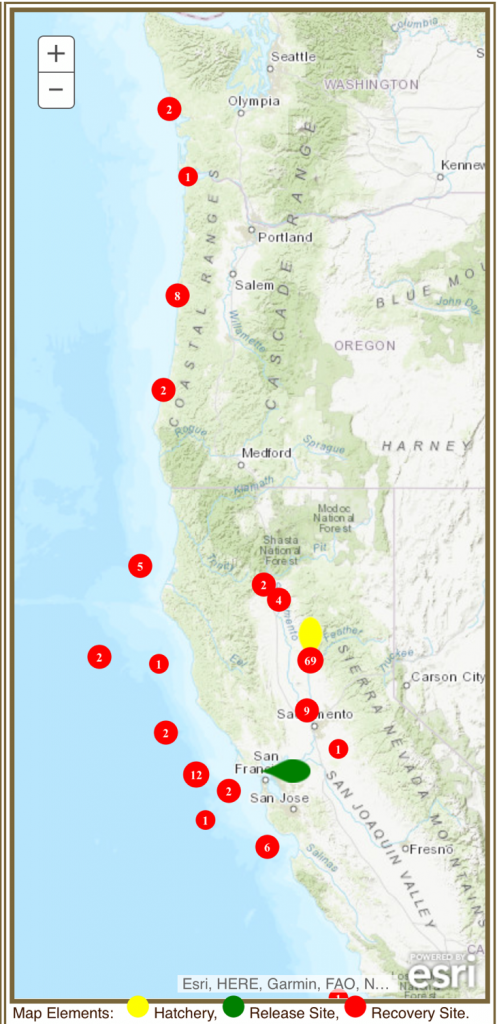

The returns from tag group #060593 (shown in Figure 3), which represented only about 3% of the total smolts releases from the Mokelumne Hatchery in 2015, exemplifies the kind of return pattern that can be achieved by a progressive hatchery program. The majority of the adults returning from this tag group to the Central Valley were to the hatchery (192), although a significant number strayed to the neighboring American River (82) and San Joaquin River and its tributaries (40). In previous years, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife achieved similar success barging smolts from the Feather River Fish Hatchery.1

Figure 1. Mokelumne River in-river fall Chinook returns (escapement) 1975-2017.

Figure 2. Mokelumne River hatchery fall Chinook returns (escapement) 1975-2017

Figure 3. Mokelumne River fall Chinook tag returns through 2017 from 101,000 Mokelumne River Hatchery smolts, tag group #060593, barged to and released near the Golden Gate Bridge.