(Editor’s Note: From time to time, the California Fisheries Blog gets requests for guest posts. We like to accommodate requests for posts that we feel, at our sole discretion, are substantive and thought-provoking. Though we discourage pseudonyms, we may, as here, allow posts without attribution when such posts allow a platform to speak out for persons who are professionally constrained. We reserve the right to edit guest posts for clarity. As with all posts on the California Fisheries Blog, guest posts do not represent the policy or opinions of CSPA.)

By “Kilgore Trout”

On Saturday (March 18, 2023), Sep Hendrickson’s “California Sportsmen” radio show hosted James Stone, current president of the Nor-Cal Guides and Sportsmen’s Association. The Association recently lobbied to close the California salmon fishing season for 2023. The discussion raised several interesting issues about the status and management of salmon.

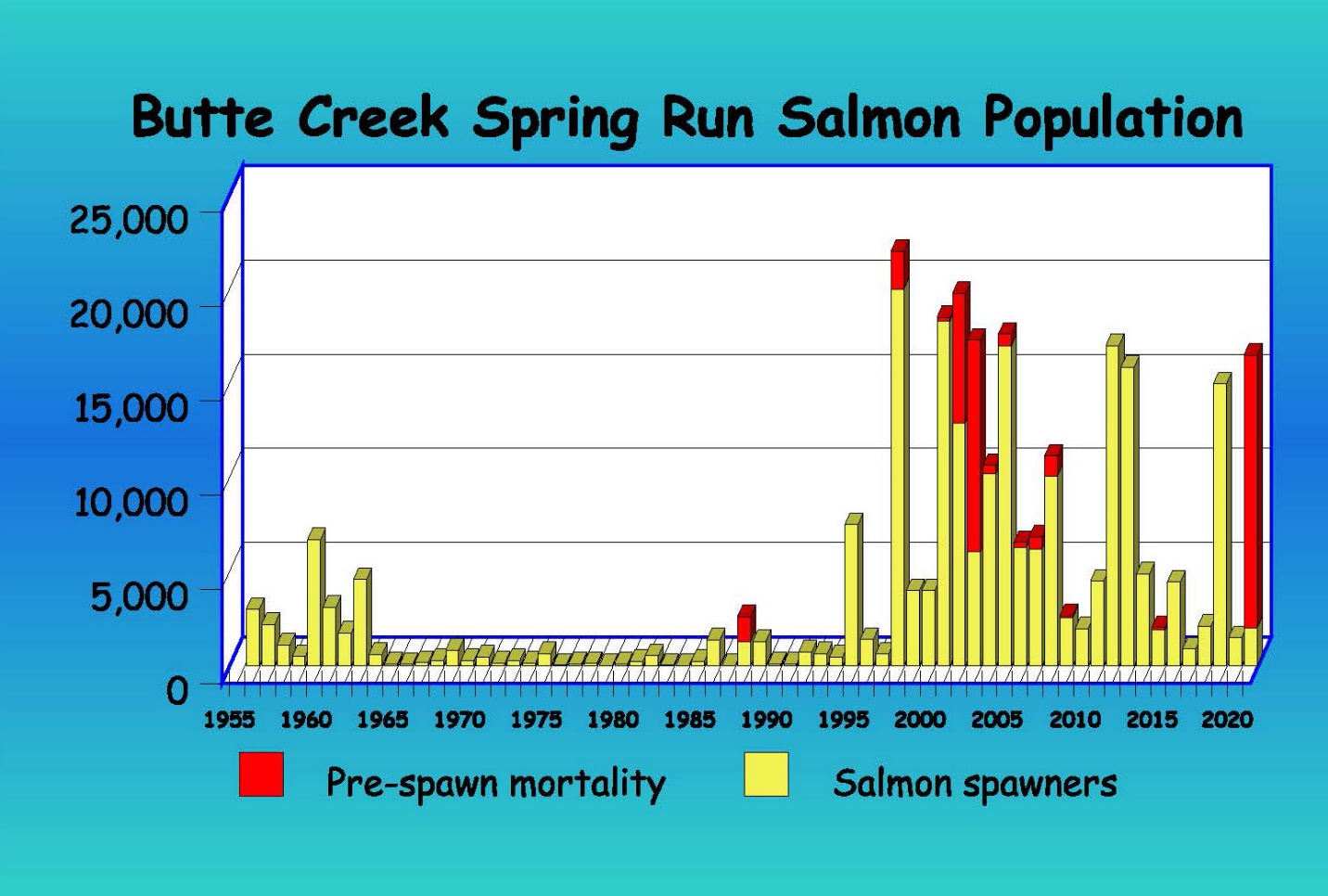

Mr. Stone questioned why regulators did not close the salmon fishery earlier than this year. He noted that in 6 of the last 8 years, the annual escapement of Sacramento fall-run Chinook salmon was below the minimum conservation objective of 122,000 adults, a dismal 75% failure rate for forecasters.

As background, the Sacramento fall-run Chinook is the dominant salmon population commercially fished offshore of California. The population is an aggregate of hatchery and natural production, dominated by hatchery production. A year’s escapement is the abundance of adults that return (in the fall) to spawn in the Sacramento River, its tributaries, and hatcheries. The following spring, the fall-run Chinook offspring of natural-origin emerge from the gravel, smolt, and migrate seaward; the hatchery-origin fish artificially produced by broodstock matings are fed and reared as fry and smolts (in raceways or ponds), then released near the hatchery, or trucked to the estuary or Bay for release.

Sep and James agreed that all too often, 100% of California’s recent salmon declines are blamed on climate change and droughts, not factors like overfishing after years of low escapement. Indeed, a NOAA study conducted after the 2008 closure of the California salmon fishery attributed the collapse primarily to poor ocean conditions, but also noted contributing factors like dry inland conditions and fishing.

Sep and James continued to discuss water management in California’s Central Valley. James reminded listeners that California’s Fish and Game Code 5937 requires dam operators to release water to protect fish. This is correct, and it seems that conservation objectives for salmon (like suitable river temperatures and minimum escapement numbers) should be established to account for environmental variations like hot summers and dry winters that contribute to poor brood years. What’s the point of establishing salmon protections if we scream “Emergency!” and toss protections aside whenever consecutive dry years put agricultural or municipal water users in a short-term bind?

But water management to conserve salmon is not as simple as host Sep Hendrickson framed it when he contended, “There is water behind dams that is oxygenated that can be added and cool at any time they want to; they choose not to.” There isn’t always enough water, and it’s not as simple as saying that politicians simply choose not to release it from dams.

Salmon juveniles emerging from the gravel near Redding must travel hundreds of river miles downstream, where they enter and transit the Delta and Bay to reach the Pacific. That means the Sacramento River must be cold enough for salmon from Redding to the Bay. At the same time, water is released from reservoir storage for agricultural and municipal uses. For there to be enough cold water in the bottom strata of Shasta Reservoir to cool the Sacramento River for salmon, water released from the reservoir in any year must both keep the river cold and retain enough water in storage so that it stays cold later in the year. Shasta’s operators must also retain enough water in storage to allow cold water management in the following year if the following year is dry.

There isn’t space here for a full discussion of Sacramento River water supply and use, or the constraints on achieving temperature (and other) requirements for salmon. This would involve considering complex topics like salmon biology, climate, flood control, drought management, federal water contracts, State water rights, Delta salinity, ocean conditions, and others. But the issues are more complex than politicians (like our Governor) simply choosing not to release water for salmon.

Recognizing the gravity of the Sacramento fall-run Chinook collapse, James Stone warned, “If we don’t raise more hatchery fish, we could possibly lose the fall run forever.” Sep Hendrickson responded, “We need a state-of-the-art hatchery. We can do this state with one hatchery, centrally located that handles everything…” James Stone told listeners they could join the Nor-Cal Guides and Sportsmen’s Association, which has lobbied since 2019 for funds (up to $100 million) for a new hatchery on the mainstem Sacramento River. Stone described it as a modern facility that would allow the trucking of fish and the return of fish, and help protect our stocks for many years. The hatchery’s objective would be to “re-colonize and re-populate the Sacramento River with hatchery fish” and “get them to spawn in the rivers and start reproducing the natural spawn.” Stone added that a healthy river is the best hatchery because it could produce millions more salmon eggs than a hatchery.

Getting funds could help if the objective of “…reproducing the natural spawn” could be achieved by supplementing the production of natural-origin salmon in the Sacramento River watershed. But would another large, production hatchery “reproduce” the natural spawn, or hasten its replacement?

After all, hatcheries in the Sacramento River watershed already produce and release millions of Sacramento fall-run Chinook. The Coleman National Fish Hatchery (Battle Creek) releases 12 million fall-run Chinook smolts annually. The Feather River Hatchery has an annual goal to release 6 million smolts, and the Nimbus Fish Hatchery (American River) another 4 million. Other Central Valley hatcheries not in the Sacramento River watershed also release fall-run Chinook. The goal of the Mokelumne River Fish Hatchery is to release 5 million smolts, with an additional 2 million released into San Pablo Bay or into acclimation pens in the ocean. The Feather River Hatchery also produces an additional 2 million fall-run Chinook to truck downstream for an ocean enhancement program. Before building another large hatchery, it seems fair to ask why releasing millions of hatchery fall-run Chinook – year after year – hasn’t already reproduced the natural spawn.

What if current hatchery practices are also exerting negative effects on Sacramento fall-run Chinook, like overfishing and unbalanced water management do? Yes, some California hatchery facilities are very old, but what if investing $100 million to bring them to state-of-the-art production levels makes at least some things worse?

Ditto for building “one hatchery, centrally located that handles everything…” We already know that very little population structure remains in the Sacramento fall-run Chinook; the variation or diversity that once existed has been greatly diminished from the time when they thrived not only in the Sacramento River, but also in large tributaries like the Feather, Yuba, and American rivers, and in numerous other smaller rivers and streams in the watershed. Large dams that eliminated nearly all the upstream natal habitat of the winter-run and spring-run Chinook are generally regarded as the primary cause of the demise of these stocks. But the dams did not eliminate nearly as much fall-run Chinook habitat because the fall-run do not migrate as far upstream to spawn. So, relative to habitat loss due to dams, did hatcheries play a larger role in the “homogenization” observed in the fall-run Chinook stock?

We know that salmon in streams do not select mates randomly, so the random mate selection in hatcheries effectively eliminates adult competition. We also know that captive rearing and feeding of juvenile salmon minimizes the mortality that would naturally occur in a river. Do juvenile salmon in hatchery ponds acquire food or avoid predators the same as fish in the wild? It also makes sense that wild juveniles migrating hundreds of miles in a river must adapt to more perilous environments than do hatchery fish transported in trucks. Are the consequences of these hatchery effects the losses of vigor, the ability to adapt to local environments and variation, and evolutionary fitness?

It seems we could better understand hatchery effects by spending some of the $100 million on modern salmon monitoring. Genetics-based tools already exist, so that all hatchery broodstock can be tissue-sampled and genotyped, with the information stored in a computer database. All hatchery offspring (millions of fish) would be effectively “tagged” and their hatchery of origin could be identified later, if they are genotyped when captured — in the fishery, after straying to the natural spawning grounds, when interbreeding with wild fish, etc. Similarly, tissues from salmon carcasses on the natural spawning grounds could be collected and genotyped (they are already surveyed every year by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife). This process would genetically “tag” the natural-born offspring in the Sacramento River and its tributaries.

These tools would allow biologists and managers to know the origin of a salmon. They could also better understand the effects of artificial propagation, such as interbreeding, on natural-origin fish. We could begin to understand if hatcheries could “re-colonize and re-populate the Sacramento River with hatchery fish” and “get them to spawn in the rivers and start reproducing the natural spawn.”

An alternative to building and ramping up another large production hatchery might be to try (mobile) conservation hatchery set-ups, to temporarily supplement wild stocks in the Sacramento River and tributaries. With genetic tagging, we could know how well the offspring survive to return and spawn, and how successful their offspring are at surviving and reproducing. We could detect if and when the rivers get healthier, and begin producing more eggs and adult salmon than the hatcheries do. We might get to a place where there is no need to clip adipose fins.

Let’s start working together to recover salmon!