Causes of the Decline of the Endangered Delta Smelt

There are multiple threats to the Delta Smelt population that contribute to its viability and risk of extinction. Chief among these threats are reductions in freshwater inflow to the estuary; loss of larval, juvenile and adult fish at the state and federal Delta export facilities and in urban, agricultural and industrial water diversions; direct and indirect impacts of the Delta Smelt’s planktonic food supply and habitat; and lethal and sub-lethal effects of warm water and toxic chemicals in Delta open-water habitats.

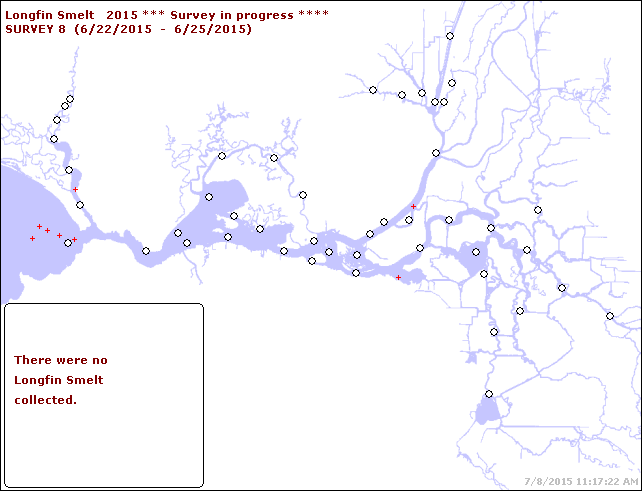

Temporary urgency change orders by the State Board have allowed reduced Delta outflow and increased Delta salinity. This has moved the Low Salinity Zone further upstream (eastward) into the Delta, thereby increasing the degree of each of these threats. During the past few drought summers, remnants of the population have been confined to a small area of the Low Salinity Zone where water temperatures barely remain below lethal levels. The change orders are an obvious and direct threat to the remnants living in the Low Salinity Zone. Further allowing these weakened standards to be violated is a direct disregard for the remnants of the population. It places them at extraordinary risk by bringing them further into the zone of water diversions, degrading their habitat into the lethal range of water temperature, further degrading their already depleted food supply, and increasing the concentrations of toxic chemicals being relentlessly discharged into the Delta.

Saving the Delta Smelt

The following are measures necessary to save the remnant Delta Smelt population:

- Keep the low salinity zone (LSZ) out of the Delta as prescribed in State water quality control plans over the last several decades. This can be readily accomplished by meeting already defined flow and salinity standards and restrictions on Delta exports. The LSZ on the Sacramento channel side should be in the wide open reach of eastern Suisun Bay between Collinsville and the west end of Sherman Island (location of Emmaton standard). It must be kept out of the Emmaton-to-Rio Vista reach just upstream in the west Delta, because this reach is confined and continually degraded by reservoir releases and warm water passing through the North Delta via Three Mile Slough to the interior of the Delta and south Delta water diversions. On the San Joaquin (south) side, the low salinity zone belongs in the wide Antioch–to-Jersey Point reach as prescribed in standards. This can be accomplished in spring and summer of dry years by maintaining prescribed flows, salinity standards at Jersey Point, installation of the False River and Dutch Slough Barriers, and opening the Delta Cross Channel (which results in positive net outflow from the mouth of Old River downstream to Jersey Point in the Central Delta). Maintaining the net positive flows in west Delta channels helps tremendously in getting salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, striped bass, and smelt from upstream freshwater spawning areas to their downstream rearing area target, the estuary’s LSZ. Keeping the LSZ in eastern Suisun Bay, as has always been an objective Delta Water Quality Plans, has huge indirect benefits as well, including greater plankton production, lower non-stressful water temperatures (conducive to growth and survival of all the Delta fish including smelt and salmonids), higher turbidity levels in the LSZ (reduced predation on and improved feeding for Delta smelt), lower invasive Asian clam concentrations in eastern Suisun Bay (which siphon off plankton and larval fish), and lower concentrations of toxins in the LSZ.

- Improve the physical habitat of the LSZ. Habitat in eastern Suisun Bay, though far better than that of the west Delta, has been continuously degraded over the past century. Fortunately, there are few levees along the north shore of the Sacramento side. However, the wave-swept shores along Antioch Hills have lost all riparian vegetation except pockets of invasive Arundo. Hillside windfarm and shoreline erosion have filled in shoreline shoals, shallows, bays and alcoves that provided rearing habitat for smelt and salmon (salmon fry are the most abundant fish in these shallows through the winter). Miles of shoreline bays, inlets, and tidal marshes east of Collinsville have been lost. On the south side of the Sacramento channel are the remnants of historic Delta marshes and islands of West Sherman Island and Sherman Lake. Gradually the riparian shoreline and shallow waters are washing away as a consequence of wind as well as ship-wake erosion. Lack of interior marsh channel circulation has also led to grand infestations of invasive non-native submergent, emergent, and floating aquatic vegetation. Like the north shore, the south shoreline of West Suisun Bay on the San Joaquin side is not leveed. Likewise, shoreline and shallow water habitats are degraded, but from industrialization. Large areas east of Antioch to Big Break are degraded much as in the area of Sherman Lake. Both the north and south East Suisun Bay channels are degraded by dredging of the two deep-water ship channels, which has resulted in the loss of shallow shoal, bay, and mudflat habitats. Virtually none of the habitats mentioned above were addressed in the grand BDCP restoration plans for the Bay-Delta. Though some of the areas have been prescribed for restoration in various mitigation plans, virtually no progress has been made toward their restoration in the last several decades.

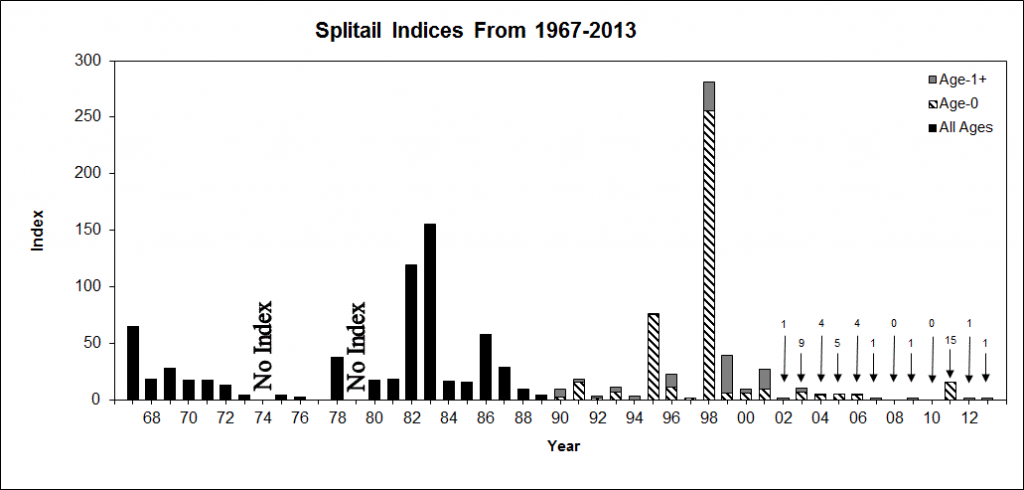

- Stock hatchery raised smelt in the LSZ. The agency-sponsored Delta Smelt conservation hatcheries could be upgraded to production status to provide juveniles to be stocked in the LSZ in late spring and summer. The population is so low now (zero 20-mm and Townet survey indices) that stocking would be helpful if not necessary.

- Provide a spring pulse flow into and through the Delta to help smelt fry transport from freshwater spawning areas downstream to the LSZ. This could include passing some Sacramento River flow through the blocked entrance to the Deepwater Ship Channel at the Port of West Sacramento. Delta inflow pulses could be provided by reservoir releases coordinated with infrequent natural flow pulses through the Delta.

- Manage tidal flows and Delta hydrodynamics, as well as water quality, on a real time basis to help maintain the LSZ in east Suisun Bay and to stimulate and sustain plankton blooms. Real time management is possible because of the many satellite-accessible data recorders in the Delta, as well as the many frequent biological monitoring surveys being conducted throughout the Bay and Delta. Active adaptive management is possible with the many flow controls available on diversions, reservoir releases, and flow splits (e.g., Delta Cross Channel).