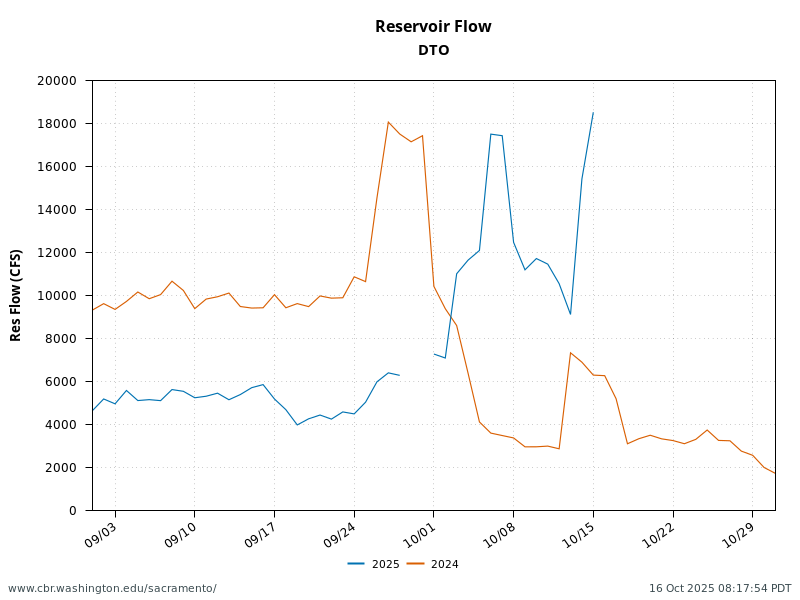

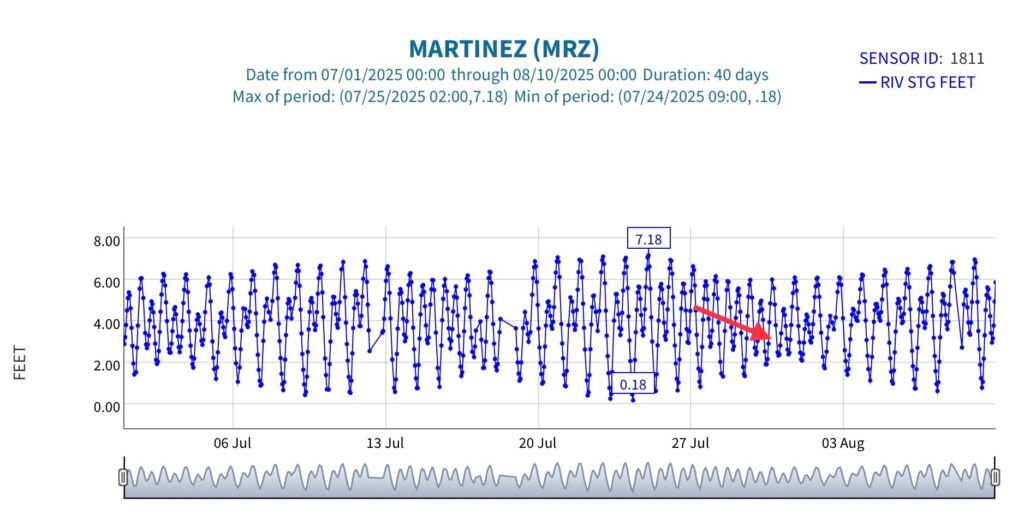

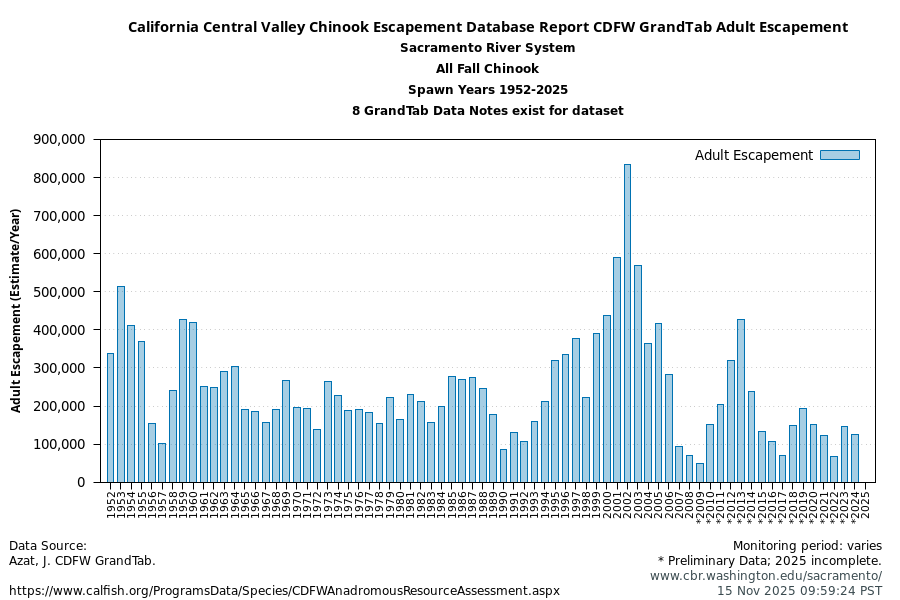

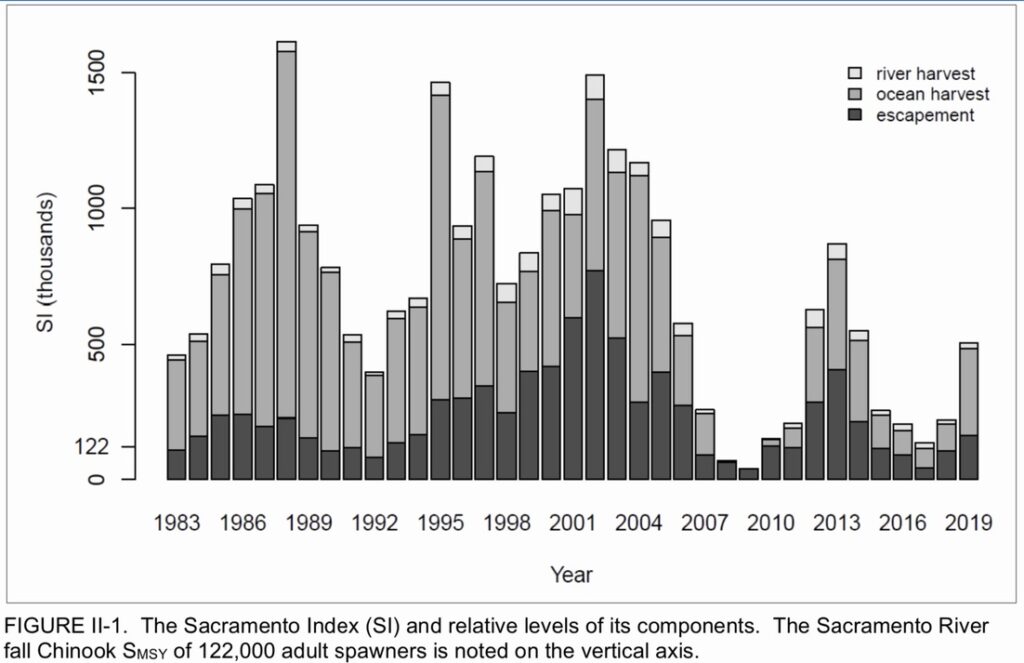

Since the year 2000, Fall Run Salmon adult escapement (run total) to the Sacramento River system (mainstem and tributaries) dropped from a peak of 400,000-800,000 to 100,000 or less (Figure 1). The lowest escapement, near 50,000 in 2009, occurred with the fishery closed. More recently, escapement fell below 100,000 in 2017 and 2022, with the fishery open. With the fishery closed in 2023 and 2024, escapement increased to near 150,000, allowing for a very limited recreational fishery in 2025.

The fishery harvests are about 50% of the fishable stock (or what could be available for escapement, see Figure 2). A normal fishery would lead to escapements under 100,000 in recent years. These escapement levels would likely lead the Pacific Fisheries Management Council and California Fish and Game Commission to restrict the fishery again in 2026.

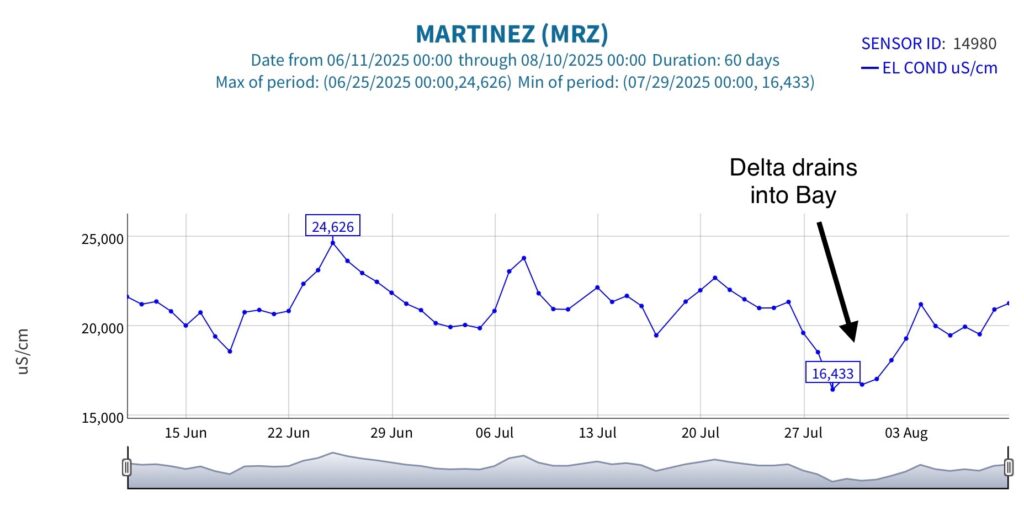

However, the agencies may be inclined to allow a fishery with some restrictions based on positive trends in habitat conditions and the higher jack salmon numbers in the limited 2025 fishery. Water years 2023 and 2024 were relatively wet, which often leads to good survival conditions, and is likely to lead to a projection of good salmon numbers available in 2026.

I am inclined to greater optimism for 2026, as I was in 2025,1 because of the likely higher numbers of salmon in the ocean and potentially returning to the rivers next year. The various factors supporting my reasoning are summarized below:

- Jack numbers were up based on escapement surveys, agency test fisheries, and the limited 2025 fishery.

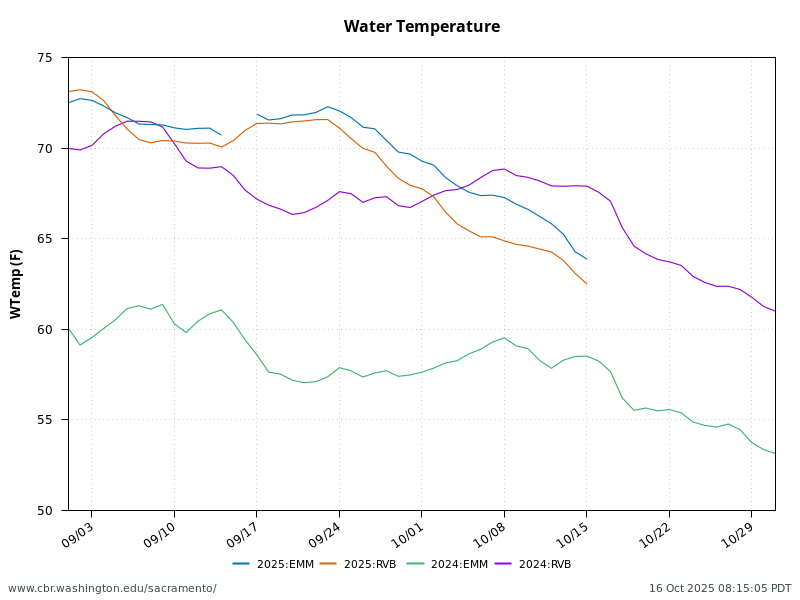

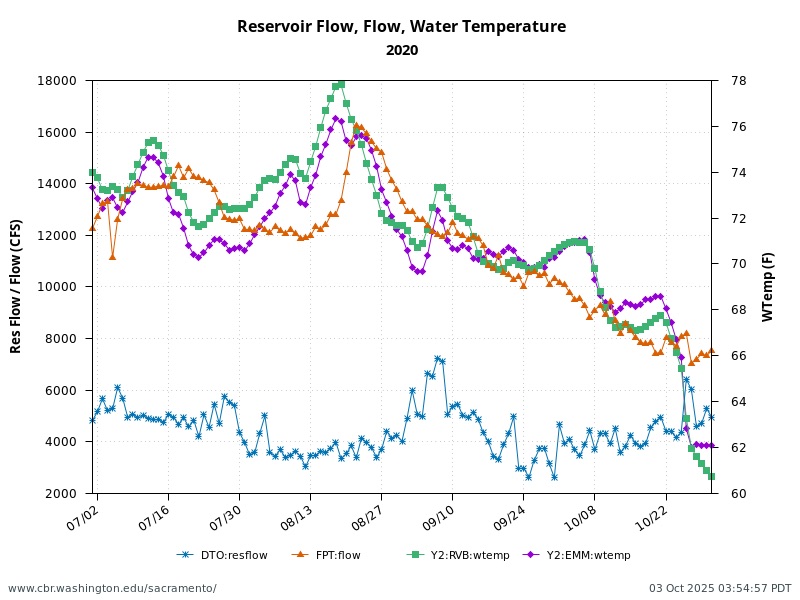

- Brood years 2023 and 2024, which will make up much of the fishable stock in 2026, likely had good survival and production in wet year 2023 and above-normal water years 2024 and 2025 (compared to dry years 2020-2022). Fishery impacts to these broodyears were also minimal in 2024 and 2025.

- Hatchery smolt production in 2023-2025 was also good, with some improvements over the 2020-2022 drought years. Hatchery smolts released to the rivers near the hatcheries likely had a much improved survival rate in 2023-2025 over that in the drought years, because of higher transport flows. Millions of hatchery smolts trucked to Bay and coast pens for release also had improved survival compared to river releases.

- Fishery restrictions in 2023-2025 likely improved wild salmon spawning numbers, leading to good wild salmon recruitment in the three wetter years.

- A 2026 fishery would likely benefit from good overall broodyear 2023 and 2024 survival and production.

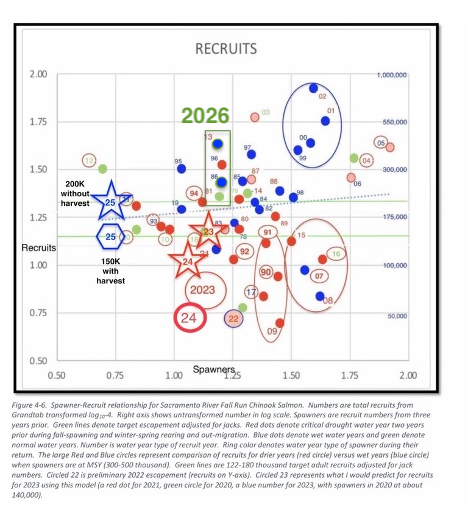

- My estimate of the fishable stock of broodyears 2022-2024 in the ocean is 400,000-800,000 two-to-four year-old salmon. Under a 50% harvest, escapement in 2026 would be 200,000-400,000 (likely somewhat less, as not all the fishable stock would spawn in 2026). I support this hypothesis with a descriptive Spawner-Recruit model that I developed (Figure 3) that has reasonably predicted escapement in the past several years.

If the fishery remains restricted for a fourth year in a row, escapement could reach or exceed 500,000 adult salmon, a number far in excess of the management target escapement of 120,000-180,000. Such a case would unnecessarily deprive commercial and recreational fisheries of the potential harvest of 200,000 or more adult salmon in the ocean and rivers in 2026.

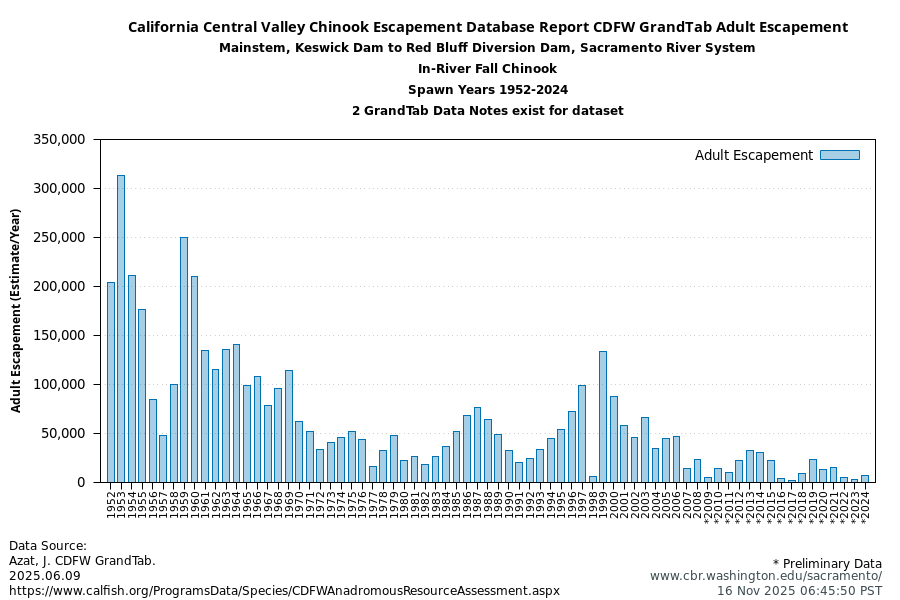

I remain concerned with the potential adverse effects on wild salmon stocks from fishery harvest (Figure 4). Limiting wild salmon harvest by adjusting fishery timing and location, restricting catches to marked hatchery fish (mark-selective fishery rules), and improving spawning, rearing, and migrating habitat, could help address these issues.

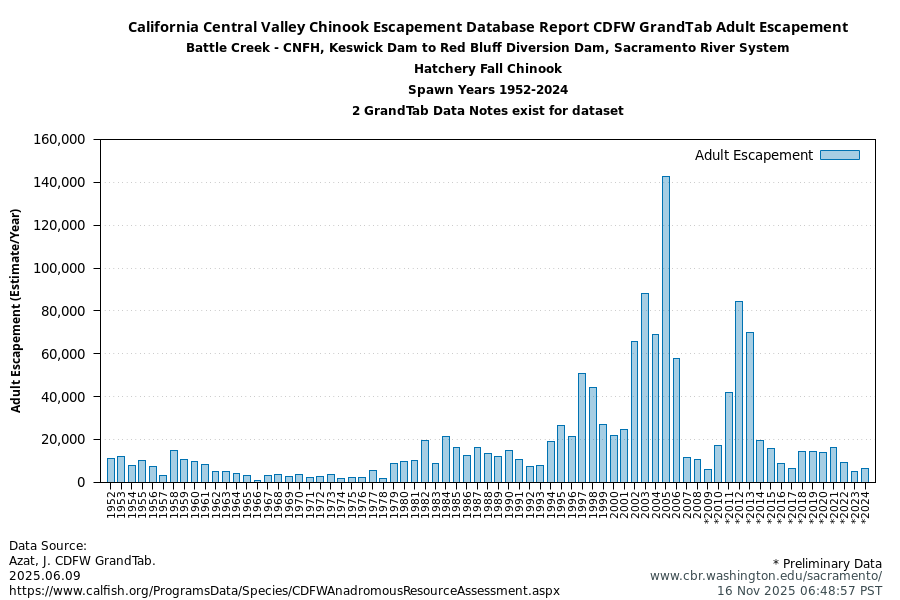

I am also concerned with the poor returns (escapement) from the Coleman Hatchery’s in-river smolt releases that result in low fishery contributions, low escapement (Figure 5), and high rates of adult spawner straying to other spawning streams. To address this problem agencies have considered higher smolt production, increased near-hatchery releases, trucking smolts to Bay-Delta-Coast, transporting eggs to Coleman from other hatcheries, hatchery fry releases to river floodplain and estuary habitats, reducing in-river predators, and improving migrating habitat during smolt releases. All of these measures could help minimize the extent of this problem.

Figure 1. Note the very high escapement around the turn of the century. The improvement is attributable to the wet decade (1995-2005), increased hatchery production, trucking hatchery smolts to the Bay-Delta, and more protective management of fisheries and water supply. Subsequent poor escapement periods are generally attributed to multiyear drought impacts and over-fishing of drought-impacted salmon broodyears.

Figure 2. A 50% harvest rate is about what has occurred over the recent decade under normal fishery regulations.

Figure 3. This complicated semi-quantitative spawner-recruit model display attempts to show that a normal spawner-recruit relationship is overwhelmed by hatchery, harvest, and water-year hydrology effects on recruitment. I predict 2026 escapement (recruits) with a normal fishery will fall into the green box (200,000-400,000) because 2023 and 2024 were wetter (blue) water years. Without a fishery, escapement would be near or above 500,000, a number well above the target escapement.

Figure 4. These spawner estimates for the upper Sacramento River represent the natural spawning escapement of the mainstem Sacramento River. The decline in this escapement component is considered a key factor in the overall decline of the Sacramento River fall-run salmon population. The decline is generally attributed to increasingly poor habitat conditions (water flows and temperature, pollution, predation, and water diversions) and over-harvest of wild or natural-born fish in the fishery.

Figure 5. Adult fall-run salmon returns to the Coleman Hatchery in the upper Sacramento River have been below 10,000 for several years. Preliminary estimates for 2025 indicate sharply higher returns to the Coleman Hatchery (near 40,000 or higher), the result of good hatchery smolt survival, no fishery for three years, and good river conditions this summer and fall.