The predator-control movement in the Delta got started around the turn of this century when efforts were initiated to reduce the Central Valley Striped Bass population by removing them from Clifton Court Forebay in the South Delta and by stopping the hatchery and pen rearing supplementation programs. Efforts under the Central Valley Project Improvement Act of 1992 (CVPIA), specifically the Anadromous Fish Restoration Program (AFRP), were beginning to make progress at restoring Central Valley fish populations including winter, spring, fall, and late-fall run Chinook, Steelhead, sturgeon, and Striped Bass. Of course, these efforts had been enormously aided by Mother Nature in the form of a series of wet years following the disastrous 1987-1992 drought that precipitated the CVPIA (and many of the endangered species listings).

Striped Bass supplementation had reached its apex. Hatchery raised yearlings were stocked by the millions. Millions of wild young stripers salvaged at South Delta federal and state pumps were placed in pens in the Bay and fed for one to two years and then released.

The end of the wet years and the beginning of the Pelagic Organism Decline in the early 2000s brought out “predator control” for the Central Valley. Federal and state water contractors planted the seed as their Delta diversions reached record levels of 6 million acre-ft. The first effort was to develop a predator removal program at the State Water Project’s Clifton Court Forebay in the south Delta. A further effort forced California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) to prepare a Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) for its Striped Bass Supplementation Program (which was approved and the program continued for several years). CDFW did not undertake predator removal in the Forebay.

The 2007-2009 drought brought a water contractor sponsored lawsuit against CDFW, and when that failed, an approach to the California Fish and Game Commission to eliminate sportfishing regulation restrictions on Striped Bass. Relying on sound science, the Commission unanimously rejected their efforts.

The recent Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP) included predator control at “hotspots” in the Delta. But BDCP has been cast aside in favor of Governor Brown’s “water fix.”

This past week FISHBIO Inc., a major contractor for the water districts in the Central Valley, posted “Can Predator Control Help California’s Native Fishes?”1 The post relates the passage of a bill in the House specifically regarding predator control to protect endangered species. While most (hopefully the Senate) will see the bill as part of the water contractors’ “smoke screen”, the bill exemplifies continued efforts on the part of water contractors in the Central Valley to place the blame and solution elsewhere. The post relates about a recent San Joaquin restoration program meeting where information on predators was presented. No mention was made of the recent record low flows in the San Joaquin or the fact that salmon numbers are directly related to flows, or that salmon cannot survive their migrations in the warm polluted waters of the San Joaquin in drier years.

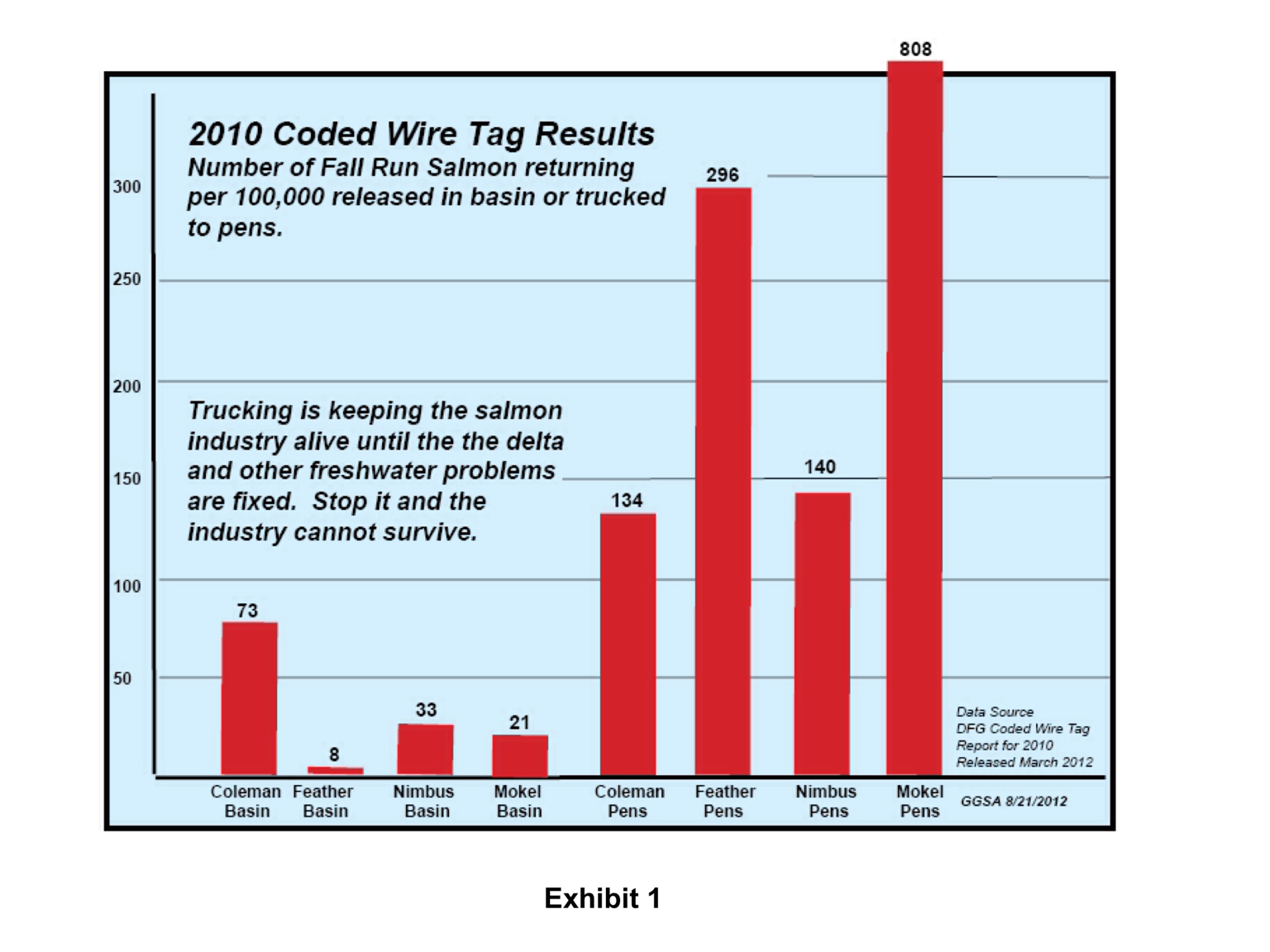

The post mentions a modeling study that shows Striped Bass could eat all the San Joaquin salmon. However, it fails to mention the abundance of young hatchery salmon prey dumped into streams at the same time that Striped Bass and other predators are attracted into the cooler tributaries by the same warm polluted waters of the San Joaquin that block young salmon from moving to the ocean. It fails to acknowledge that upstream dams intercept the early natural pulse flows of cold water that would enable wild salmon fry to move out of the tributaries before waters warm sufficiently for predators to become active. It fails to mention that Striped Bass are also at record low levels. It fails to mention that hundreds of thousands of recovery program hatchery smolts have been dumped into the San Joaquin that serve to encourage predators to switch to salmon (these hatchery fish should be barged to and through the Delta to the Bay – an action that should be funded by the water contractors). And, for the record, it ignores the fact that aquatic life is a mutual eating society and hatchery salmon and steelhead smolts prey on wild salmon fry.

The post concludes with “This month’s actions to amend the Commerce, Justice and Science Appropriation Act may finally open the door to predator control programs in California – a hopeful step towards remedying a long-term problem that continues to spin out of control.” FISHBIO had better prepare for interviews on FOXNEWS.

(AUTHOR’S NOTE: predators including native fishes, birds, and marine mammals, as well as non-native fish like the Striped Bass and other state protected gamefish, take a huge toll on our native endangered salmon, steelhead, trout, smelt, and sturgeon. Predation is probably a primary causal factor as an indirect effect of water diversions on native fish. What is needed is a comprehensive recovery program like that on the Columbia River2. That program addresses the full spectrum predators like pikeminnow, terns, cormorants, marine mammals, and even non-native shad, stripers, smallmouth, walleye, and northern pike. However, unlike California erratic efforts to manage fisheries, the Columbia success-story, at least to date, can be attributed to progressive water management and hatchery-wild fish, science-based, recovery programs.)