Species in the Spotlight

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) has included the Sacramento River Winter-Run Chinook Salmon in its “Species in the Spotlight,”1 one of the eight species under NMFS’s jurisdiction nationwide that are most at risk of extinction.

On its website, NMFS describes the condition of Winter-Run (in italics below):

State and Federal Agencies, public organizations, non-profit groups and others in California’s Central Valley have formed strong partnerships to save Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon. Efforts to protect winter-run Chinook salmon include restoring habitat, utilizing conservation hatchery programs, closely monitoring the population, and carefully managing scarce cold water. Additional key actions needed to safe guard winter-run Chinook salmon from further declines include:

- Improving management of Shasta Reservoir’s storage in order to provide cold water for spawning adults, eggs, and fry, stable summer flows to avoid de-watering redds, and winter/spring pulse flows to improve smolt survival through the Delta. (Note: badly needed as these actions have been generally lacking especially in the past two years.)

- Completing the Battle Creek Salmon and Steelhead Restoration Project and reintroducing winter-run Chinook salmon to the restored habitat. (Note: Badly needed with little progress made in regard to Winter Run.)

- Reintroducing winter-run Chinook salmon into the McCloud River. (Note: Badly needed with little progress made.)

- Improving Yolo Bypass fish habitat and passage so juveniles can more frequently utilize the bypass for rearing and adults can freely pass from the bypass back to the Sacramento River. (Note: Badly needed with little progress made.)

- Managing winter and early spring Delta conditions for improved juvenile survival. (Note: During the past four years of drought, Delta outflow has almost always been inadequate for emigrating juveniles.)

- Conducting landscape-scale restoration throughout the Delta to improve the ecosystem’s health and support native species. (Note: Little progress has been made.)

- Expanding LSNFH facilities to support both the captive broodstock and conservation hatchery programs; (Note: In progress. The hatchery program released 600,000 smolts in February last year and 400,000 in February this year. The releases are made in Redding where flows have been too low for good survival because Shasta Reservoir is retaining all its inflow. Much greater survival would be achieved if the smolts were trucked downstream to mid-river and then barged to the Bay.)

- Evaluating alternative control rules used to limit incidental take of winter-run Chinook salmon in ocean fisheries. (Note: Ongoing and in progress. Fishery harvest for all races of Chinook will likely be curtailed this year.)

Number One Threat

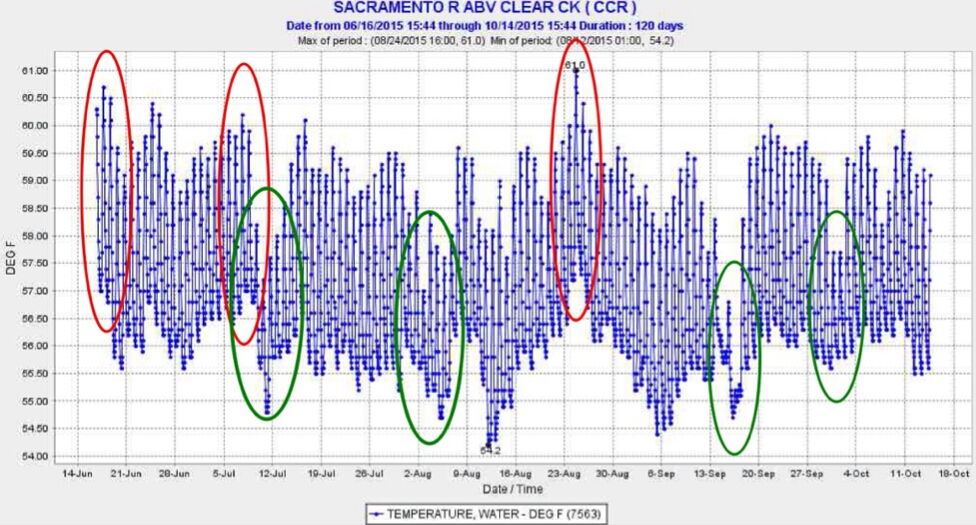

The most serious threat to Winter Run and the major cause of the nearly complete loss of the past two years’ production relates to the first item in the above list: improving management of Shasta Reservoir cold water storage is essential. The change from a 58°F daily-average water temperature standard at Redding (last summer) to 53°F as proposed by NMFS will greatly help by alleviating sporadic lethal conditions that occurred last summer (Figures 1 and 2).

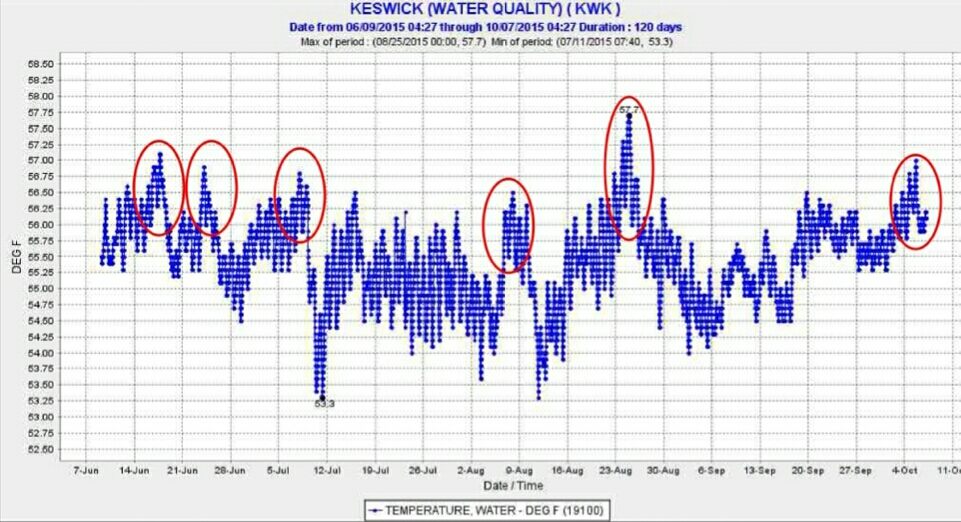

Achieving non-lethal conditions through the summer is possible by conserving Shasta Reservoir’s cold-water pool, which is best achieved by reducing inputs of warm water from Whiskeytown Reservoir (from Lewiston-Trinity reservoirs) into Keswick Reservoir via the Spring Creek Powerhouse (Figure 3). This source of warm water made up about 15% of the release to the Sacramento River from Keswick Reservoir, and required use of extra Shasta’s cold-water pool water to meet the relaxed temperature standard of 58°F in the upper Sacramento River below Keswick in Redding.

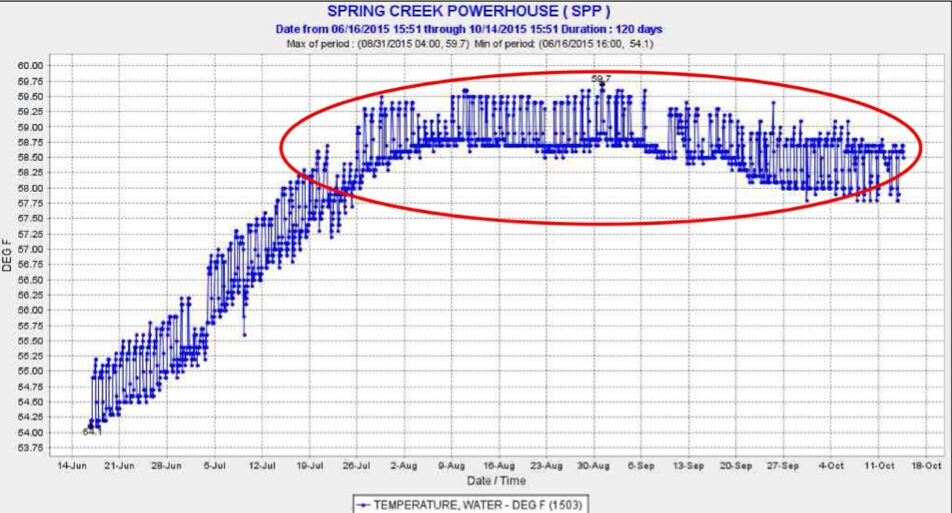

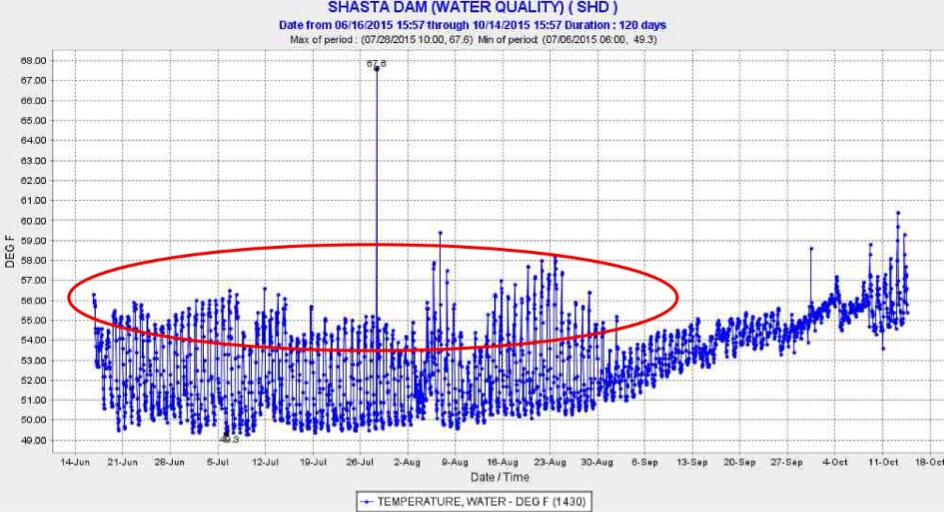

Another source of warm water to Keswick Reservoir was from daily afternoon peak power releases from Shasta Dam (Figure 4). High releases in afternoons raised water temperatures in Keswick Reservoir, requiring more cold-water pool release to compensate for warm water inputs. Apparently, the operations were too complicated for Reclamation to maintain the required 58°F average daily temperature at the mouth of Clear Creek (CCR gage: Figure 1). Operations at other times (e.g., first week in August) indicate clearly that Reclamation had the capability of keeping the water temperature well below lethal levels.

Figure 1. Lethal water temperature extremes for salmon eggs and fry (red circles) near Redding in summer 2015. Green circles denote non-lethal conditions that can be maintained with proper management of Shasta’s cold-water pool.

Figure 2. Episodes of high water temperature in Keswick Reservoir (red circles) in summer 2015. Peaks were due to hydropower peaking and specific operations of the Shasta Temperature Control Intake Tower to powerhouses at Shasta Dam.

Figure 3. Warm water (red circle) entering Keswick Reservoir from Whiskeytown Reservoir via Spring Creek Powerhouse in summer 2015. Daily range of 1°F is due to hydropeaking operations.

Figure 4. Warm water releases (red circle) from Shasta Reservoir during daily hydropeaking operations in summer 2015. Release water temperatures in the first week of August and September were lower because of lower afternoon hydropower peaking releases of warm water along with more night-morning cold water pool releases.