The Problem – Sturgeon are Declining

A day-long symposium on March 3, 2015, Sturgeon in the Sacramento–San Joaquin

Watershed: New Insights to Support Conservation and Management, put the onus on sport fishermen to save Central Valley sturgeon. Contributors suggested that to maintain a healthy population of white sturgeon, mortality of adult females has to be eliminated, sport fishing harvest of adults should be halted, and sport fishing should be confined to no more than catch-and-release, with no fishing during the spawning season.

The stated reason for such constraints is that there is a 15- to 20-year period until first spawning, and that thereafter sturgeon often spawn only once every five years. “[I]t is essential not to lose the enormous re-population potential of each spawning female.”

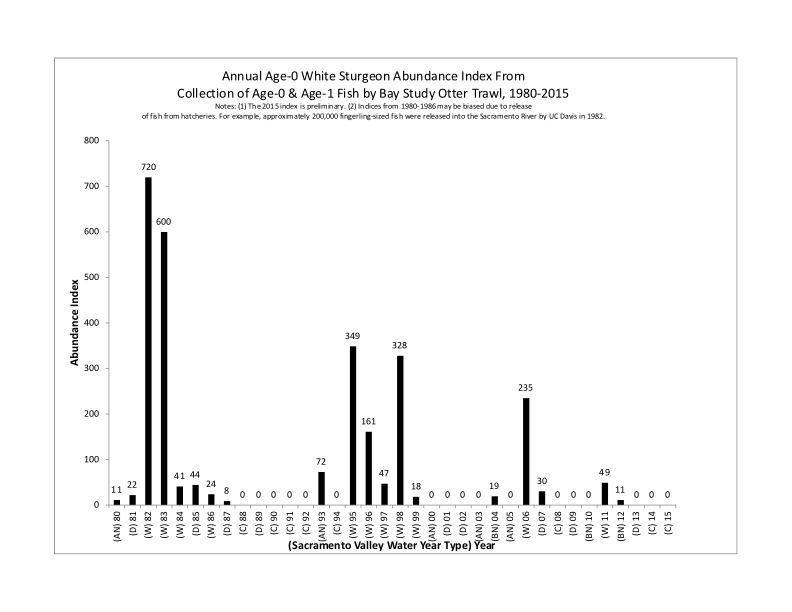

The contributors also noted that strong year classes of sturgeon only occur in wet years when young survival is high. The 2006 year class was the last year class to contribute strongly to the adult population. Essentially what they are saying is that survival of young is so poor and intermittent that recruitment into the adult population is too low to allow any sport fishing harvest.

Of note, there was no mention whether the number of adults spawners has been or is now a limiting factor in the number of recruits produced in the very wet years. Such a state would indeed be a great concern. If the number of eggs laid in very wet years with the present adult population was insufficient to saturate the existing spawning and rearing habitat with young, then the population would be on an accelerated path to extinction. However, if the number of eggs laid is sufficient to saturate the habitat and recruitment (survival of young) is only a function of habitat conditions, then the reason for poor recruitment is not over-fishing but poor or degraded habitat. The intermediate condition where both factors are important is possible if not likely. How the fishery should be managed would also be different in the three conditions.

Also important are any changes in the trajectory of the habitat conditions. If habitat is being gradually degraded by man’s direct effects or climate change, that too can drive the population downward by reducing the production capacity of habitat or increasing the natural mortality of sturgeon. Sport fishing harvest has to be sensitive to such changes, if only to being falsely blamed for any decline or accepting a need to change even to the point of mitigating for the other effects.

Approach to Recovery

Based on the symposium and its summary paper it appears that the onus has been put on sport fishing as the cause as well as the solution to declining sturgeon populations. There was little mention about the effect of habitat conditions (other than the historical imposition of dams). There was mention of stranding and rescue of sturgeon in the Valley bypasses. “An individual-based model indicated that in the absence of rescue, the current population of green sturgeon in the river would have declined by 33% over 50 years (Thomas et al. 2013).” This anecdote was offered more as evidence that harvest should be curtailed as opposed to being a major factor in the decline that should be fixed. The fact is that large numbers of adult sturgeon get “lost” or become stranded or die in the Yolo and Sutter bypasses and in the Colusa Basin Drain each year, especially in wet years when their eggs are most needed.

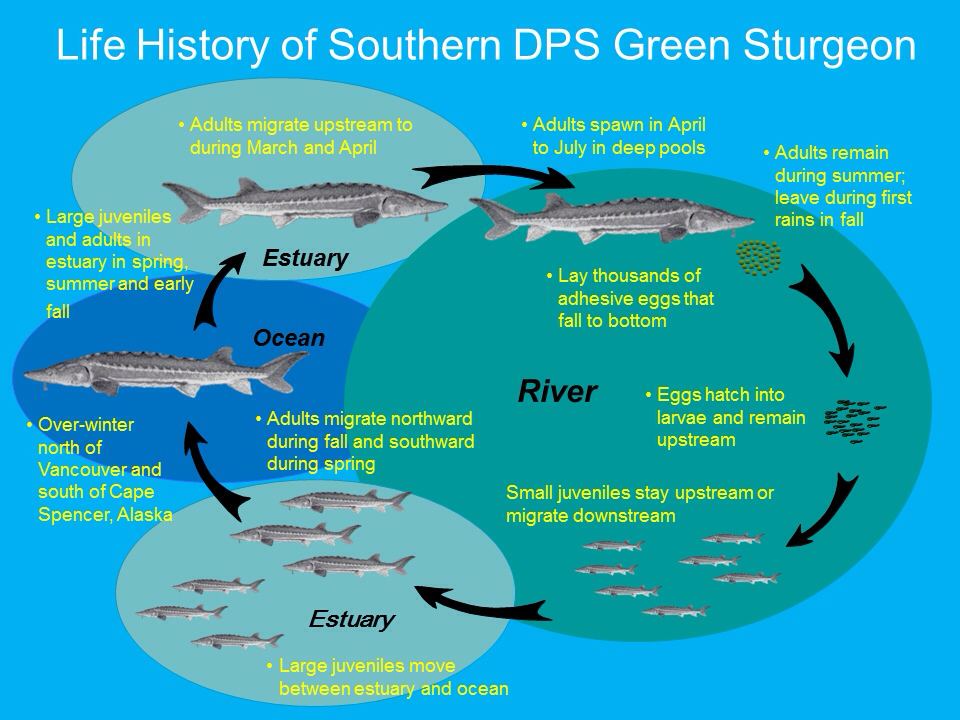

There was discussion of juvenile survival. “[L]ittle is known of the swimming capacities of larval sturgeons, though the risk of larval sturgeon entrainment is likely influenced by both the ontogeny of swimming capacity and the interactions of sturgeon with water diversions.

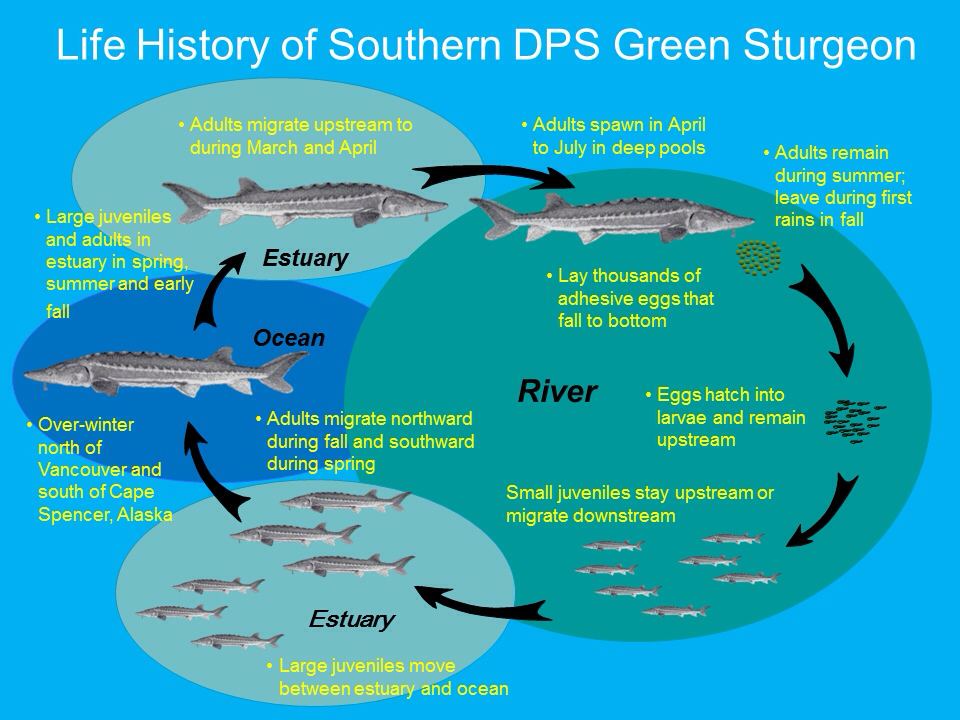

Green sturgeon were also much more likely to become impinged upon screens (than White Sturgeon). “Of the more than 3,300 water diversions located in the Sacramento–San Joaquin watershed, the majority (ca. 98%) are estimated to be unscreened. The number of green sturgeon entrained and killed by unscreened water diversions is unknown….. Therefore, efforts to increase the number of migrating green sturgeon that successfully reach estuarine and marine environments should focus on juvenile life history stages, and take into account the behavioral and physiological changes that accompany such a migration… Substantial recruitment depends on extremely high Delta outflows during winter and spring. The mechanisms underlying this relationship are the subject of on-going investigations, but are likely some combination of adult attraction to upstream spawning grounds, suitability of spawning substrate, and survival of age–0 fish during the migration downstream to the estuary.” (Emphasis added)

Symposium Conclusions and Recommendation

There were three primary conclusions and associated recommendations from the symposium.

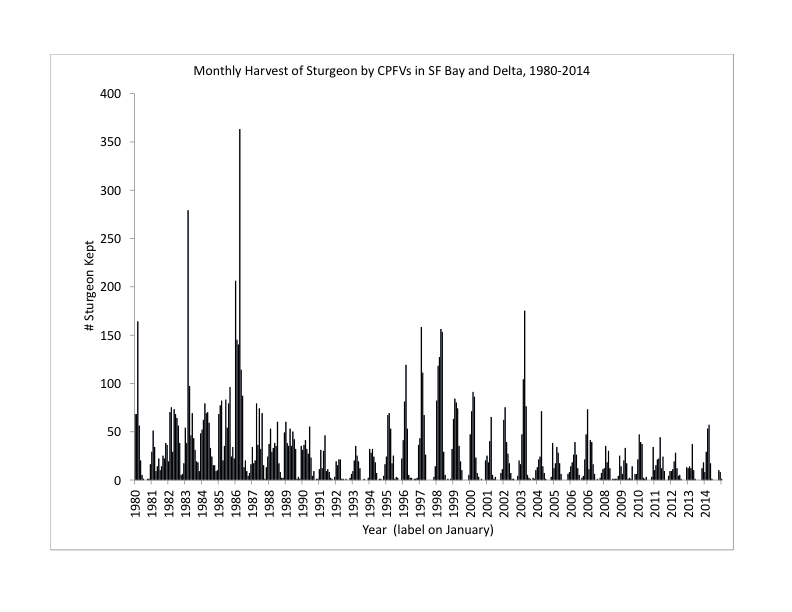

- Maintain a healthy population of white sturgeon by eliminating mortality of adult females. Sportfishing harvest of adults should be halted, or fishing at least confined to catch-and-release outside of the spawning season. Having survived the 15- to 20-year period until first spawning, and subsequently only spawning every 5 years, it is essential not to lose the enormous re-population potential of each spawning female. Loss of a single spawning female that will produce several hundred thousand eggs each time she spawns. Comment: There was no mention of reducing the stranding of sturgeon in the flood bypasses (Yolo and Sutter) despite stating the important contribution of 24 rescued in a limited effort in a 2010 overflow event. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of adult sturgeon stray into the bypasses each year. Many are lost or unable to find suitable spawning habitat. That compares to the several hundred harvested each year by sport fishermen (see figure below) under strict harvest regulations, out of an adult population of 25,000-50,000.

- Protect and restore critical key habitat in order to conserve and reestablish to conserve and reestablish sturgeon populations. Gravel beds are critical for successful spawning and egg survival. Deep holes are critical as energetic refuges for sturgeon holding in the river.Comment: No mention was made that many of these key spawning habitats are degraded in dry years by low flows and high water temperatures in the late spring spawning season. Demersal adhesive eggs and hatched young are subject to lethal water temperatures (>65oF) in dry years. Low flows also contribute to starvation, predation, and reduced downstream transport.

- Take a holistic approach to life history and habitat research and monitoring. This should include a robust program of conventional mark–recapture to determine population size, population year–class composition, and mortality rate—in addition to advanced telemetry and habitat mapping methods. This approach should also include continuous monitoring of dissolved oxygen, the most critical environmental factor for oxyphilic sturgeons: they are broadly tolerant of wide ranges in temperature, salinity, and flow that are all much less critical factors for their population success. Comment: Water temperature, flow, entrainment, and predation are the key factors of poor recruitment (survival) in non-wet years. These factors are far more important for sturgeon in the long run than the harvest of several hundred adult sturgeon each year from a population of 25-50 thousand adults.

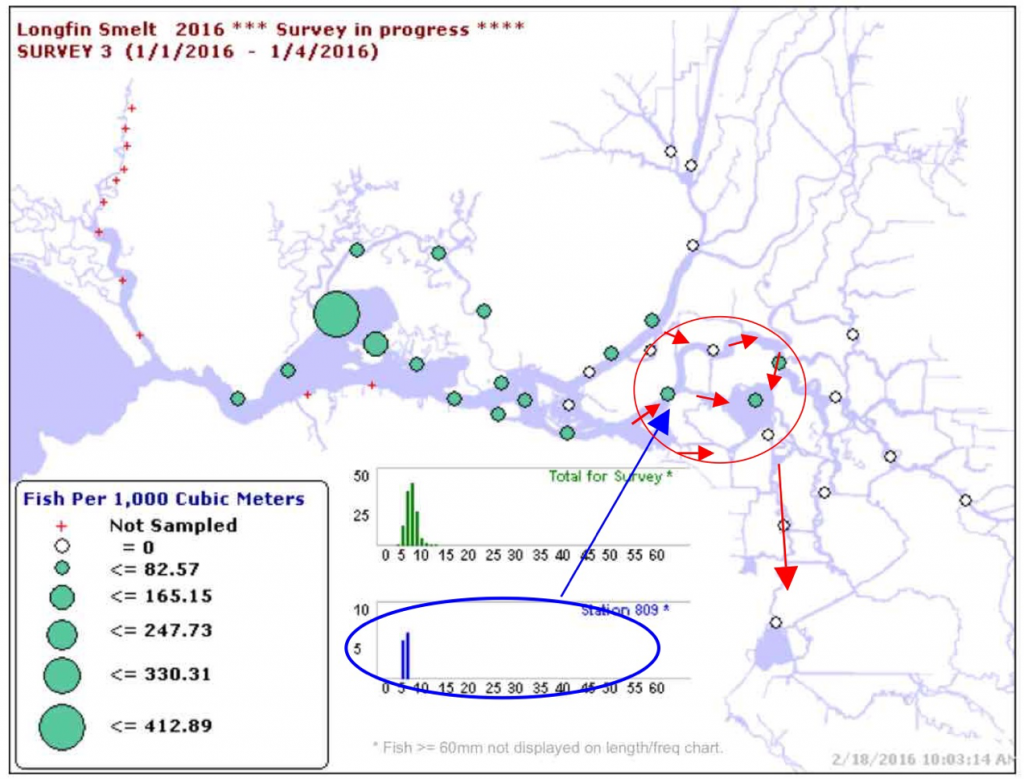

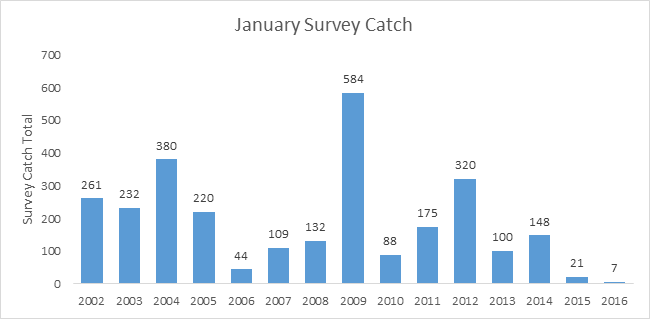

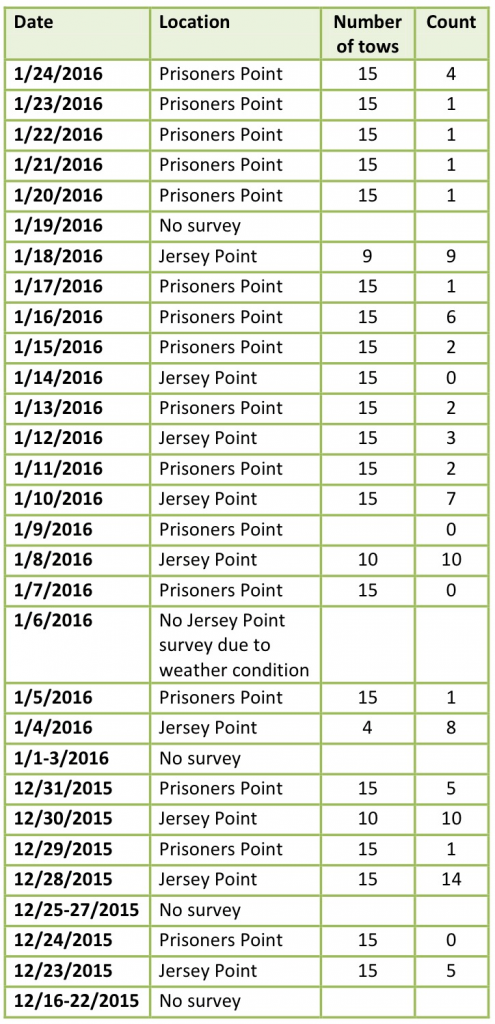

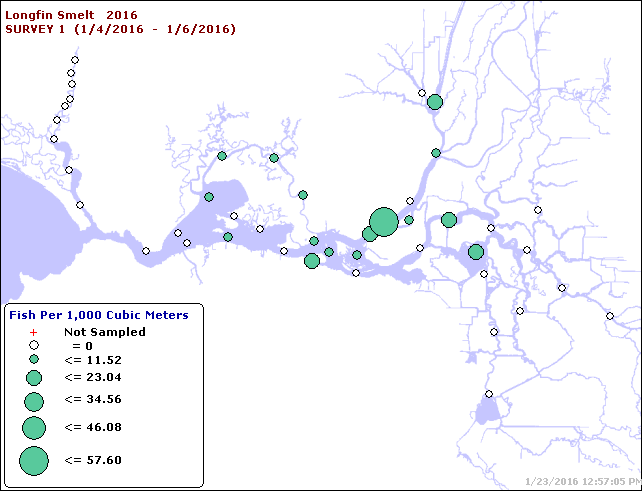

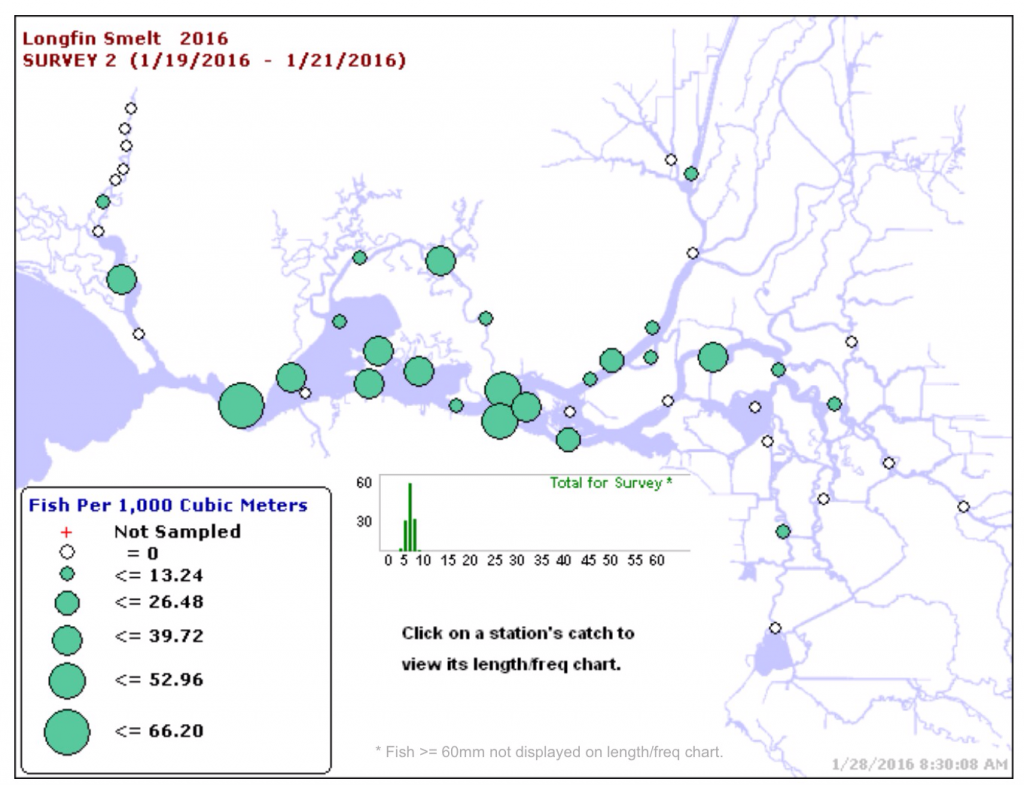

Figure 1. Record low indices for Jan-Feb 2016 in Kodiak Trawl Survey

Figure 1. Record low indices for Jan-Feb 2016 in Kodiak Trawl Survey