As noted in the first blog of this series, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) is responsible under the Endangered Species Act for protecting the endangered Winter Run Chinook salmon of the Sacramento River. But when the US Bureau of Reclamation (USBR or Bureau) and the Department of Water Resources (DWR) have asked NMFS to comment on proposed changes in Central Valley Project operations during the present four-year drought, NMFS has consistently concurred, often going against its own previous prescriptions and advice. As a consequence, the Winter Run salmon were put at great risk, decimating the 2014 and 2015 year classes and again placing the population at the brink of extinction.

April 8, 2014 Drought Operations Plan

On April 8, 2014, the Bureau and DWR issued a 2014 Drought Operations Plan, in which they proposed low releases in the Sacramento River in April and May:

Keswick releases will be held to no greater than 3,250 cfs, or as determined necessary to reasonably target no more than 4,000 cfs at Wilkins Slough, unless necessary to meet nondiscretionary obligations or legal requirements;

The critical phrase here is “nondiscretionary obligations.” It is the view of NMFS, as described in its Biological Opinion for the Operation of the State Water Project and Central Valley Project, that the Bureau of Reclamation does not have the discretion to release less water to Sacramento River Settlement Contractors than 75% of contracted amounts. Thus, low April and May flows called for in the 2014 Drought Operations Plan were overwhelmed by calls for water by the Settlement Contractors.

April 8, 2014 NMFS Letter on Sacramento River Water Temperature Management

On April 8, 2014, NMFS wrote a letter1 to the Bureau and DWR in response to their April 8, 2014 Drought Operations Plan. In that letter, NMFS concurred with the Plan, but highlighted a concern regarding deliveries to the Settlement Contractors:

“Winter-run Chinook salmon viability and Sacramento Settlement Contractor deliveries: Reclamation is working with Sacramento River Settlement Contractors on options to shift a significant portion of their diversions this year out of the April and May period and into the time frame where Keswick releases are higher to achieve temperature objectives on the upper Sacramento River. The willingness and cooperation of the settlement contractors in this effort would allow a modified diversion pattern and create the benefit of increased Shasta Reservoir storage at the beginning of the temperature control operations and increased availability of water to these senior water rights holders in this critically-dry year. This deferral of irrigation would allow implementation closer to the lower range of the Keswick release schedule for April and May, as identified in Section V of the DOP (Drought Operations Plan).

Thus the agencies and the Settlement Contractors were left to work out on a voluntary basis a mechanism to keep enough cold water in Lake Shasta to protect Winter Run salmon throughout the summer and fall. The State Water Board approved the Plan.

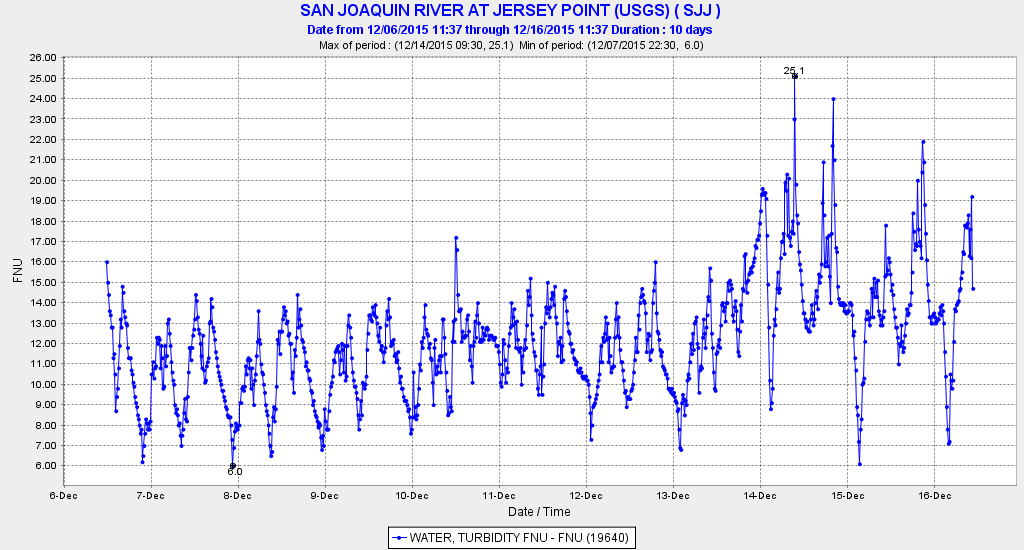

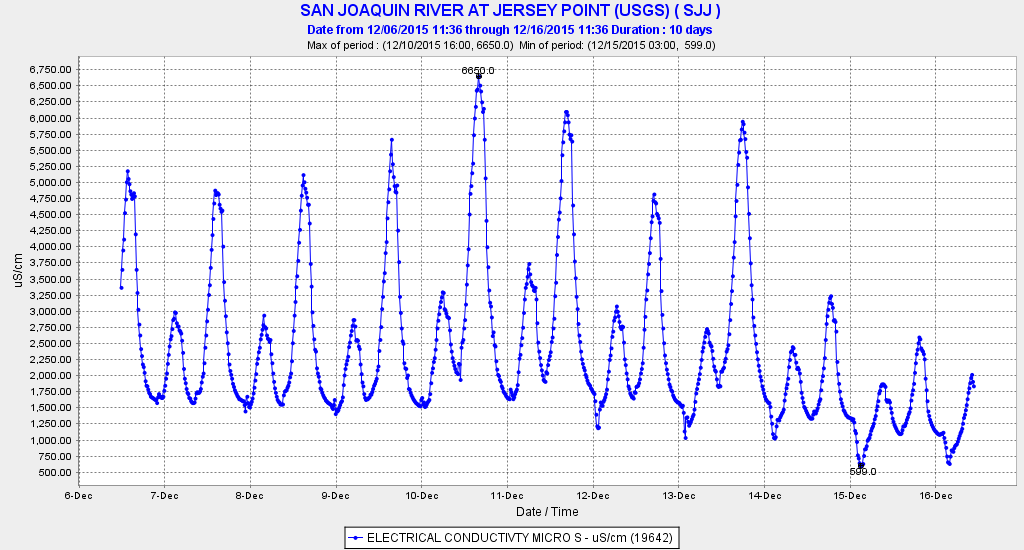

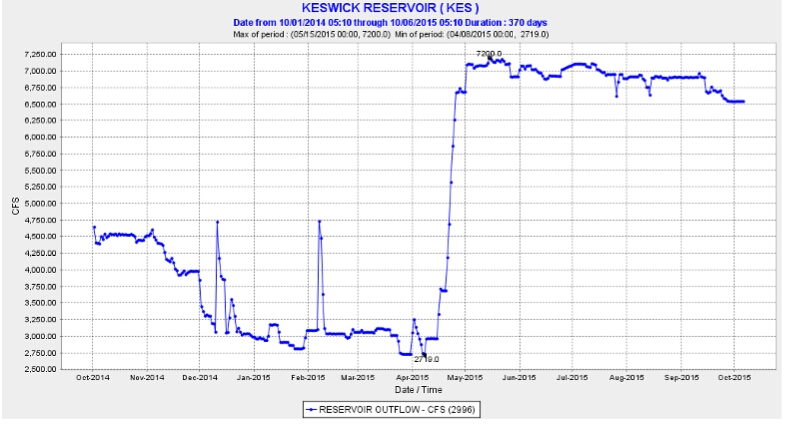

It didn’t work. Though releases from Shasta in April, 2014 were low, the Bureau ramped up releases from Shasta to the Settlement Contractors in early May (Figures 1 and 2), and cold water in Lake Shasta was depleted by the end of August.

Figure 1. May 2014 releases from Keswick to the Settlement Contractors were far above those advised by NMFS (

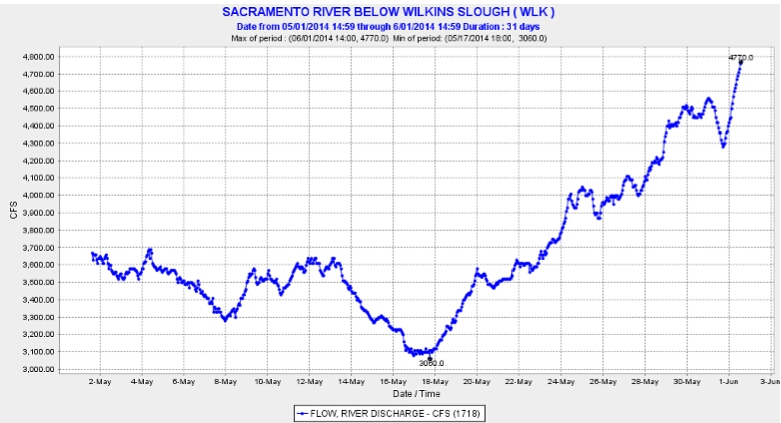

Figure 2. May 2014 releases from Keswick to the Sacramento River were diverted by Settlement Contractors upstream of the Delta. Contrast flow at Wilkins Slough (~25 miles north of Woodland) with releases from Keswick in Figure 1: most flow increases over the month were diverted north of the Delta.

January 29, 2015 Letter on Sacramento River Water Temperature Management

On January 29, 2015, NMFS wrote a letter to the Bureau and DWR in response to a new January Temporary Urgency Change Petition (TUCP) to the State Board.2 In its January 29, 2015 letter, NMFS’s acknowledged lessons from 2014 regarding water temperature:

Temperature management is critical. Salmon rely on cold water, particularly during early life stages when fish are young and vulnerable. Shasta and Keswick dams block endangered winter-run Chinook from accessing their native cold water habitat in the Upper Sacramento and McCloud Rivers, so their eggs and fry are particularly vulnerable to high summer temperatures. Data from the Sacramento River indicate 2014 temperatures were at levels that impact the survival of juvenile salmon and steelhead. We found that the 2014 temperature criterion was exceeded starting in August, resulting in approximately 95% mortality of eggs and fry upstream of Red Bluff Diversion Dam. As of December 16, 2014, an estimated 390,000 juvenile winter-run Chinook salmon passed Red Bluff, compared to 1.8 million in the previous brood year and 850,000 in brood year 2011, the year of the winter-run collapse (see Nov. 18 USFWS/CDFW/NOAA Fisheries presentation to State Water Board). This is the fewest winter-run Chinook juveniles per female spawner passing Red Bluff in 11 years.

March 27, 2015 Letter

However, by the end of March, 2015, NMFS was once again tiptoeing through a proposal by the Bureau to repeat the previous year’s disaster. On March 27, 2015 NMFS once again concurred with the proposed TUCP, even while highlighting the “conflict” between Winter Run salmon and deliveries to the Settlement Contractors. 3

The Project Description meets all of the required aspects of the contingency plan required in Action I.2.3 .C, as follows:

- Reclamation has provided an assessment of additional technological or operational measures that can increase the ability to manage the cold water pool.

- Reclamation notified the State Board, through filing the TUC Petition, that meeting the biological needs of winter-run and the needs of resident species in the Delta, delivery of water to nondiscretionary Sacramento Settlement Contractors, and Delta outflow requirements per D-1641 , may be in conflict in the coming season.

- In conclusion, NMFS concurs that Reclamation’s Project Description is consistent with Action I.2.3.C and meets the specified criteria for a contingency plan. … Furthermore, the best available scientific and commercial data indicate that implementation of the interim contingency plan will not exceed levels of take anticipated for implementation of the RPA specified in the CVP/SWP Opinion.

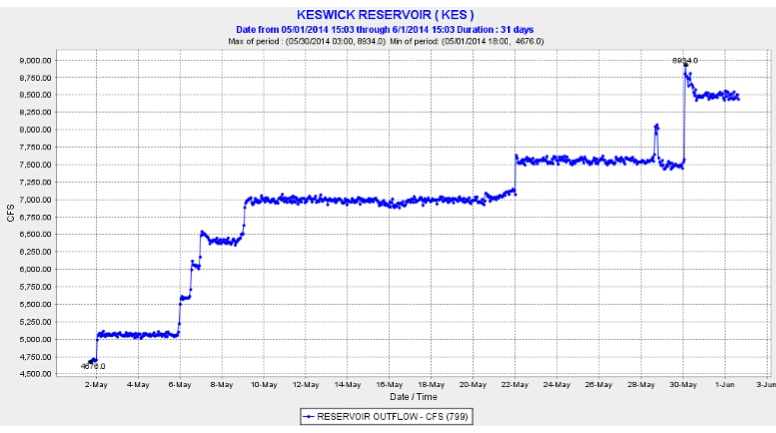

And once again in 2015, no one stepped up to maintain cold water in Shasta Reservoir in April and May (Figure 3).

Figure 3. In 2015, releases to the Settlement Contractors ramped up in April and were high throughout May.

July 1 Letter4

By July 1, 2015, NMFS was already issuing a post-mortem.

“NMFS acknowledges that storage in Shasta Reservoir at the beginning of the temperature management season in June, and the quantity and quality of the cold water pool, will not provide for suitable winter-run habitat needs throughout their egg and alevin incubation and fry rearing periods.”

Final Comment

We should expect more from the federal agency mandated to protect our endangered salmon. At a minimum, NMFS should have not concurred, in 2015 (or in 2014, for that matter), and should have called out the fact that added take of Winter Run would occur, further jeopardizing the viability of the species through direct mortality and degradation of their critical habitat.

Regardless of the legal merit of NMFS’s position that it does not have authority under the Endangered Act to limit deliveries to the Settlement Contractors, its failure to defend listed Winter Run gave cover to the Agency that has that authority: the State Water Board. CSPA, the Bay Institute and others asked the State Water Board in February, 2015 and again in the spring to reduce 2015 deliveries to the Sacramento Valley Settlement Contractors to save the Winter Run (and to protect Delta smelt). In an Order denying Petitions for Reconsideration of the 2015 TUCP’s filed by CSPA and others, the State Water Board offered the rationale:

However, at the time the changes were approved, the tradeoff appeared to be reasonable based on the information available at the time, including biological reviews from DWR and Reclamation and concurrence from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and California Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) (collectively fisheries agencies) with the changes. For these reasons, the petitions for reconsideration of the past Executive Director actions are denied. 5

- http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/Central_Valley/ Water%20Operations/2014_04_08_nmfs_drought_operations_ plan_letter_enclosure.pdf ↩

- http://www.usbr.gov/mp/drought/docs/2015-01-29_NMFS_TUCP_response_letter.pdf ↩

- http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/Central_Valley /Water%20Operations/nmfs_determination_on_contingency_plan_and_tuc_petition_-_march_27__2015.pdf ↩

- http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/waterrights/water_issues/programs/drought/ docs/tucp/2015/stellejr_nmfs_070115.pdf ↩

- http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/waterrights/water_issues/programs/drought/ tucp/docs/20151215_draftorder.pdf ↩