Restored tributary spring creek of Scott River, Klamath River tributary, with abundant juvenile Coho salmon. (See YouTube video for underwater view of countless juvenile Coho salmon rearing in this creek.)

A recent post on the KCET website by Alastair Bland spoke of efforts to save salmon on the Klamath River. I add my perspective in this post.

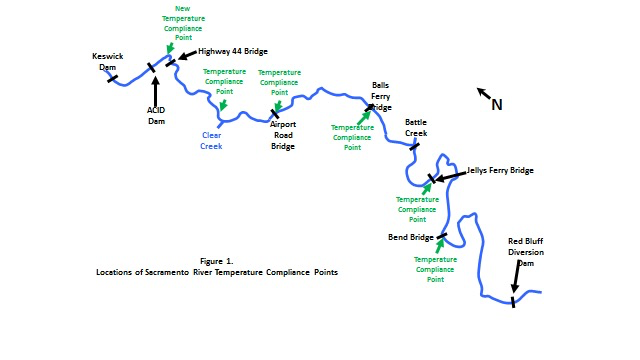

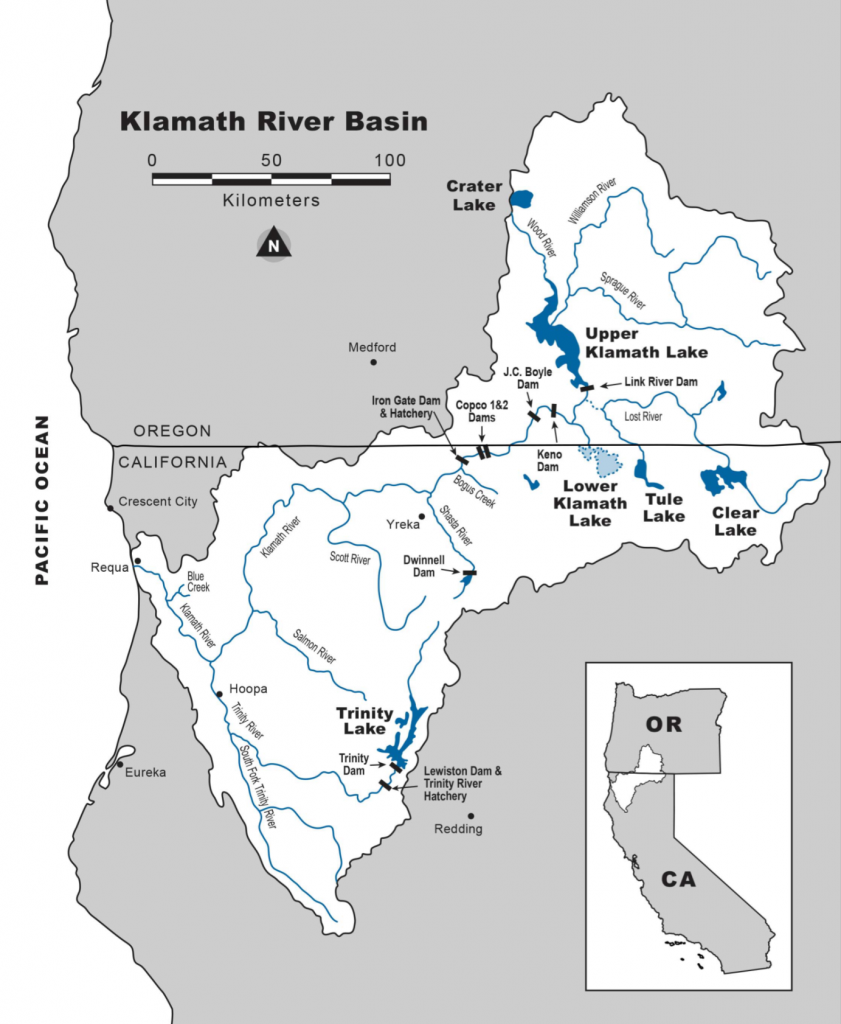

I have been involved in the Klamath salmon restoration on and off for nearly 30 years. In my experience, the runs of salmon and steelhead keep declining because not enough gets done and because there is lack of progressive management. The Klamath is a big watershed (Figure 1). I tried to sit in the middle of one element of the process a few years ago on the Scott and Shasta Rivers, the Klamath’s two main upstream salmon tributaries below Iron Gate Dam. I found there were not just two sides involved in conflict, but really five: tribes, government agencies, ranchers-landowners, a power company, and environmentalists. There were even sides within sides. The four tribes often did not agree or work together. The four fish agencies often could not agree. The two states did not always agree, and individual state agencies disagree, resulting in conflicting water rights, water use, and water quality regulations. Counties and cities disagree. Neighboring Resource Conservation Districts differ in approaches. Many citizens want a new state carved from the two states. Some landowners love salmon and beavers, and others do not. Then there are the big watershed owners: private timber companies, US Forest Service, and Bureau of Land Management that manage forest watersheds differently under a wide variety of regulations and approaches that often do not protect salmon. I watched county sheriffs try to lead landowners in policy and enforcement, with a willingness to enforce vague trespassing rules on rivers and creeks. I watched as State Water Resources Control Board members toured watersheds and met with tribes and local leaders in an effort to resolve conflicts in over-appropriated watersheds. I watched as CDFW staff tried to enforce stream channel degradation and water diversion regulations on private and public lands.

While some progress gets made, it is too slow to save the native fish. Coho and spring-run Chinook are hanging on but slowly going extinct. Fall-run Chinook are supported by hatcheries but still declining. The iconic Klamath and Trinity Steelhead are silently and slowly fading away.

For decades, the various sides have waged war over water, dams, and property rights. The watersheds and fish have suffered as “Rome” burned. Some folks have worked hard to save what is left (e.g., Blue Creek watershed). Over the decades many battles have been waged and much compromised. Lawsuits abound. Commercial and sport fishing get constrained more and more each year. Fewer California residents make the trip north to fish the Klamath each year.

There remain many intractable problems that may never be resolved. The upper watershed in Oregon, mainly around Klamath Lake and the Sprague River, suffers greatly from agricultural development and attendant water quality issues that are unlikely to go away. Much watershed damage has already occurred from timber cutting, urban and agricultural development, roads, fires, and floods. Global warming will continue to reduce rainfall and essential over-summer snowpack throughout the Klamath watershed.

Despite the grim outlook, I have found there are a host of potential actions that can help even before we get to the long-awaited four-dam removal. We need to stop the bleeding, save the patient, and start recovery. Many of the treatments and tools are already available. Some are willingly provided by Mother Nature (e.g., water and beavers). There are many diverse efforts and treatments already underway on a small scale that can be expanded and coordinated. Lessons learned can be better shared.

To get the process moving faster, I offer the following recommendations:

To get the process moving faster, I offer the following recommendations:

- Move toward making the Klamath tributaries, the Salmon, Scott, and Shasta rivers, salmon sanctuaries like Blue Creek on the lower Klamath, an effort being coordinated by the Yurok Tribe. Allow the Karuk Tribe to coordinate on the Salmon River (give them a grant to do this). On the Scott and Shasta Rivers, allow ranchers to coordinate. The Nature Conservancy is already involved in the Shasta River, as Western Rivers Conservancy is in the Blue Creek Sanctuary.

- Re-adjudicate water rights and water quality standards on the Scott and Shasta rivers. I know these are “fighting words”, but it must be done now. At least start this process, starting with the State’s new groundwater regulations. Vital portions of both rivers sit dry much of the year from surface diversions and groundwater extraction. Hundreds of thousands of young salmon and steelhead literally dry up every spring and summer, including tens of thousands of endangered Coho salmon. State laws prohibit this, as do State Board regulations, yet it continues on a large scale. Make the State enforce the laws.

- List Klamath spring-run Chinook as a federal and state endangered fish. They have become extinct from the Scott and Shasta rivers in my lifetime. They hold on in the Salmon River. They need and deserve full protection of the state and federal endangered species acts.

- Fully implement federal and state recovery plans for salmon and steelhead. Get funding.

- Re-introduce Coho and spring-run Chinook salmon to tributaries where populations are or are near extinction, including tributaries above dams.

- Rehabilitate hatchery programs on the Klamath and Trinity rivers. Develop conservation hatchery elements within these existing programs to promote wild genetic strains of salmon and steelhead in the tributaries.

- Reconnect the upper Shasta River to allow salmon and steelhead access. This process was started by the Nature Conservancy and tribes, but is long delayed and unfunded.

- Fully fund and implement a salmon and steelhead rescue program for young stranded in tributary spawning rivers.

- Improve access of spawning salmon and steelhead to historic spawning grounds blocked or hindered by irrigation dams, road crossings, or low streamflow.

- Ensure the ongoing development of the Klamath-Trinity Coho Salmon Biological Opinion for operation of the Shasta-Trinity Division of the federal Central Valley Project adequately protects and helps restore the endangered Coho salmon.

- Require the California Resources Agency to take a leadership role in making the Klamath a priority.

Figure 1. Klamath watershed. (Source DOI.)

For more on the Klamath recovery see the following: