Improving Yuba River Fisheries

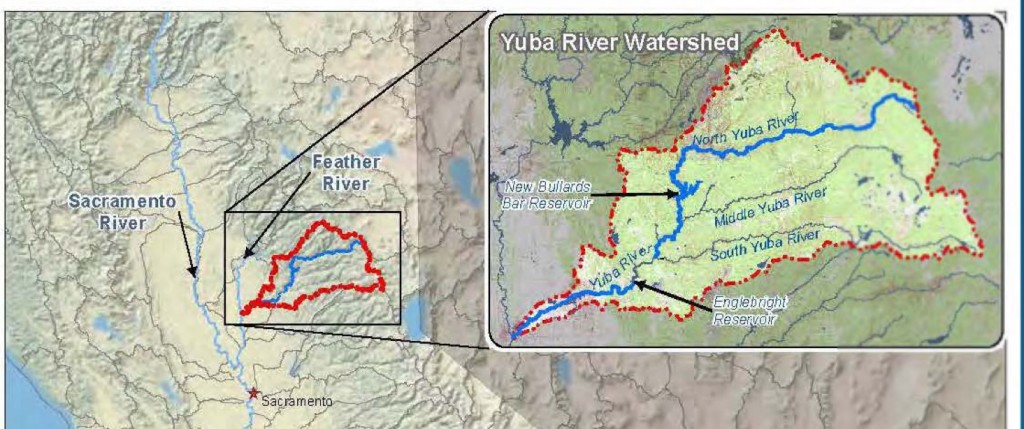

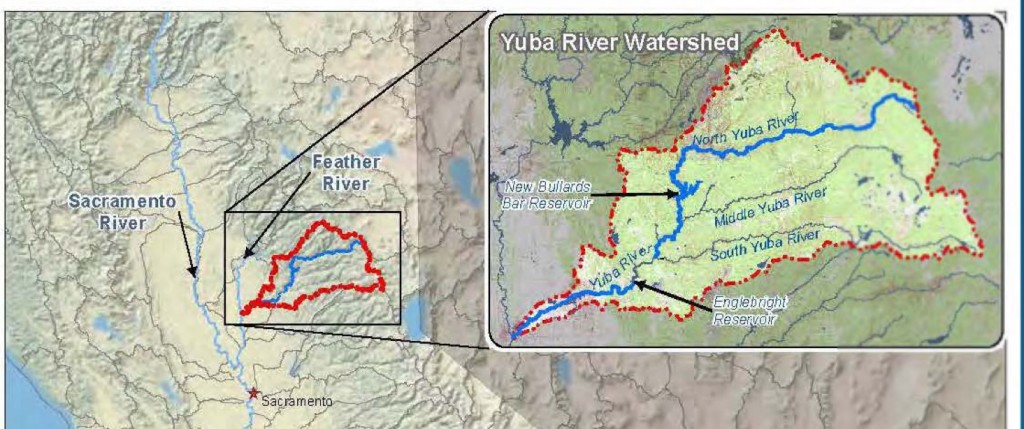

The Yuba River (Figure 1), including the lower river below Englebright Dam and its three upper forks and two reservoirs, provides a substantial fisheries resource. But it could provide much more.

Overall, the Yuba has a long complicated story with a colorful history that goes back to the gold rush and hydraulic mining in the last two centuries. Nearly two decades ago the CALFED program took on the Yuba fisheries as a special case. Options in these management planning efforts have included building a hatchery, trucking salmon and steelhead above the dams, removing dams, providing better upstream passage at dams, raising young salmon in rice fields, and enhancing spawning and rearing habitat in the lower river below Englebright Dam. Last year the National Marine Fisheries Service published its Central Valley Recovery Plan for threatened and endangered salmon and steelhead that included actions for the Yuba River. As prescribed in the Recovery Plan, The Yuba Salmon Partnership Initiative recently came to an agreement to trap and haul salmon above New Bullards Bar Reservoir to the North Yuba. The US Army Corps of Engineers and Yuba County Water Agency have also teamed up to enhance fish habitat and passage, and recently asked for public input. Their responsibility stems from the dams, flood control, water supply, and hydroelectric production on the Yuba River.

Figure 1. Yuba River is a tributary of the Feather River in the Sacramento Valley north of Sacramento, California. The lower river flows about 25 miles from Englebright Dam to to its mouth on the Feather River. New Bullards Bar reservoir on the North Yuba completed in 1970 is one of the largest in California, with storage of 966,000 acre-feet.

Status of Fisheries

Lower Yuba Trout Fishery

The gem of the Yuba is its lower river “blue-ribbon” wild trout fishery that extends from Englebright Dam downstream to Daguerre Dam and below, a total of about 20 river miles. The trout here are predominantly wild, except for some stray Feather hatchery steelhead smolts that migrate up from the Feather River, and for wild and hatchery trout from upriver that pass downstream from the dams. The wild trout of the lower Yuba have their own distinct character, likely derived from mixed genetics including steelhead. They grow quickly due to year-round near-optimal water temperature and to abundant tailwater insects supplemented with salmon eggs and fry. Trout survive well in the reach between Englebright Dam and Daguerre Dam in part because striped bass and other predatory fish cannot ascend Daguerre’s ladders. They are also protected by strict sport fishing regulations that limit gear, harvest, and season.

Lower Yuba Steelhead Fishery

The lower Yuba steelhead fishery is very limited, made up of small numbers of Feather hatchery strays and a very few wild steelhead. It is much the same case as in the lower Sacramento River near Redding, where wild resident trout dominate the fishery. There is no steelhead stocking on the lower Yuba, although many Feather hatchery steelhead smolts migrate into the lower Yuba and take up residence.

Spring Run Chinook Salmon

The number of spring run Chinook is also small, and is made up mostly of stray Feather River hatchery fish. Small numbers of adult spring run spend the summer milling below Englebright dam waiting to spawn in early fall. The population suffers from the flawed “summer run” genetics of the Feather River hatchery program, lack of spawning habitat below Englebright, and competition and interbreeding with fall run in the lower Yuba.

Fall Run Chinook Salmon

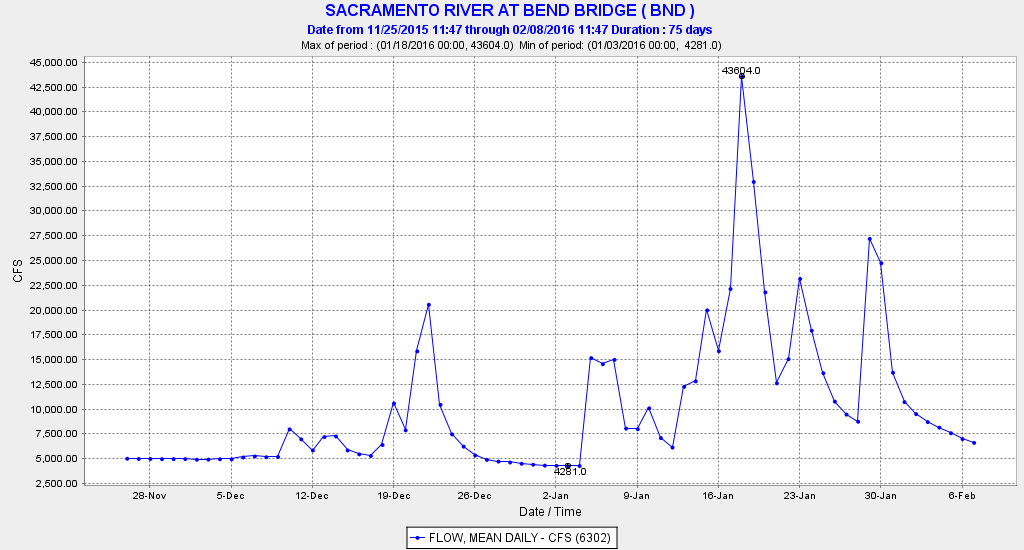

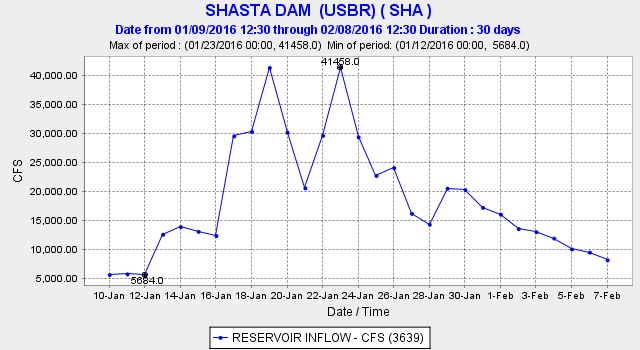

Abundant some years and not in others, the fall run salmon follow the trends of the Feather hatchery fall run, mainly because they are mostly Feather hatchery strays or their offspring. Like other Central Valley fall run, production suffers severely in drier years when winter flows are low and unable to carry newly emerged fry to their nursery areas in the Delta and Bay. Habitat and survival is poor for fry that remain in the rivers because of a lack of backwater and floodplain habitat and woody in-stream cover. The Yuba, like the Sacramento and its other tributaries the Feather and American, and like the San Joaquin and its tributaries, suffers from winter-spring reservoir storage of most of the dry year runoff, leaving little flow to help young salmon emigrate or to provide floodplain rearing habitat.

Recommended Actions

I recommend the following actions to help improve the populations of the target fish species to protect them from extinction, but also to improve the dependent sport and commercial fisheries.

- Adult Spring Chinook should be captured at Daguerre Dam and trucked above the dams to spawn. Young thus produced should be captured and transported below Daguerre Dam in wetter years or trucked to Verona (mouth of Feather River) and barged to the Bay in drier years. Spring run should not be allowed to spawn in lower Yuba where they interbreed with fall run or have their redds destroyed by fall run spawners.

- Spawning and rearing habitats in the lower Yuba should be enhanced as proposed in the above-described programs. Of greatest need are woody cover in low flow channels and low flow spawning and rearing habitats such as alcoves, side channels, and connected oxbows.

- Winter-spring flows in the lower river should be enhanced when necessary to improve emigration of young salmon and steelhead in wet, normal, and below normal water years given sufficient reservoir inflows and storage supplies.

- In dry years, wild fall run salmon and steelhead young should be captured in winter and spring at Daguerre Dam and trucked to Verona and then barged to the Bay.

- A conservation hatchery should be considered for the lower Yuba to enhance the spring run salmon and steelhead populations. Alternatively, repurposing of a portion of the Feather River Fish Hatchery to achieve this enhancement should be considered The first order of business would be to develop appropriate genetic stocks; the second would be to increase production and contribute to sustainable fisheries.

These and other suggestions are also generally prescribed in the following blog post by Dr. Peter Moyle (UC Davis): http://www.ppic.org/main/blog_detail.asp?i=1890 .