In a recent 2020 essay in SAN FRANCISCO ESTUARY & WATERSHED SCIENCE, authors Nobriga and Smith describe striped bass as a “phantom predator” that for a century has been secretly driving down their “naïve prey,” the Delta smelt. The authors hypothesize that Delta smelt were much more abundant that the earliest regular monitoring data would indicate, and that striped bass did most of this damage to the Delta smelt population before there was widespread monitoring of either Delta smelt or striped bass.

The authors’ analyses, interpretations, and conclusions have a major omission. They fail to include the potential role of other native and non-native predatory fish in driving down the population of Delta smelt, regardless of the actual abundance of Delta smelt in the eighty years after stripers were introduced to the Bay-Delta in 1879 and 1882. Dozens of other predatory species also proliferated in the Delta over that past century, especially over the past several decades. Today, those other predatory species are far more abundant than the striped bass, and many are equal if not greater potential predators on young smelt than striped bass. In fact, striped bass are more likely to prey on juveniles and adults of other predator species than on smelt.

The authors are from the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the federal agency bound to protect the Delta smelt under the Endangered Species Act. The authors used “California Department of Fish and Wildlife fish monitoring data to provide evidence for a ‘phantom predator’ hypothesis: that ephemeral but persistent predation by Striped Bass helped to marginalize Delta Smelt before the estuary was routinely biologically monitored.”, The authors argue against “a misinterpretation that Striped Bass had little contemporary effect on Delta Smelt,” and “contend that the Delta Smelt population has declined steadily since Striped Bass were introduced to the estuary, and that has masked a substantial predatory effect of Striped Bass on Delta Smelt.” The article describes and supports a hypothesis that striped bass remain a problem for Delta smelt, despite the precipitous decline in the production of juvenile striped bass over the past century or so.

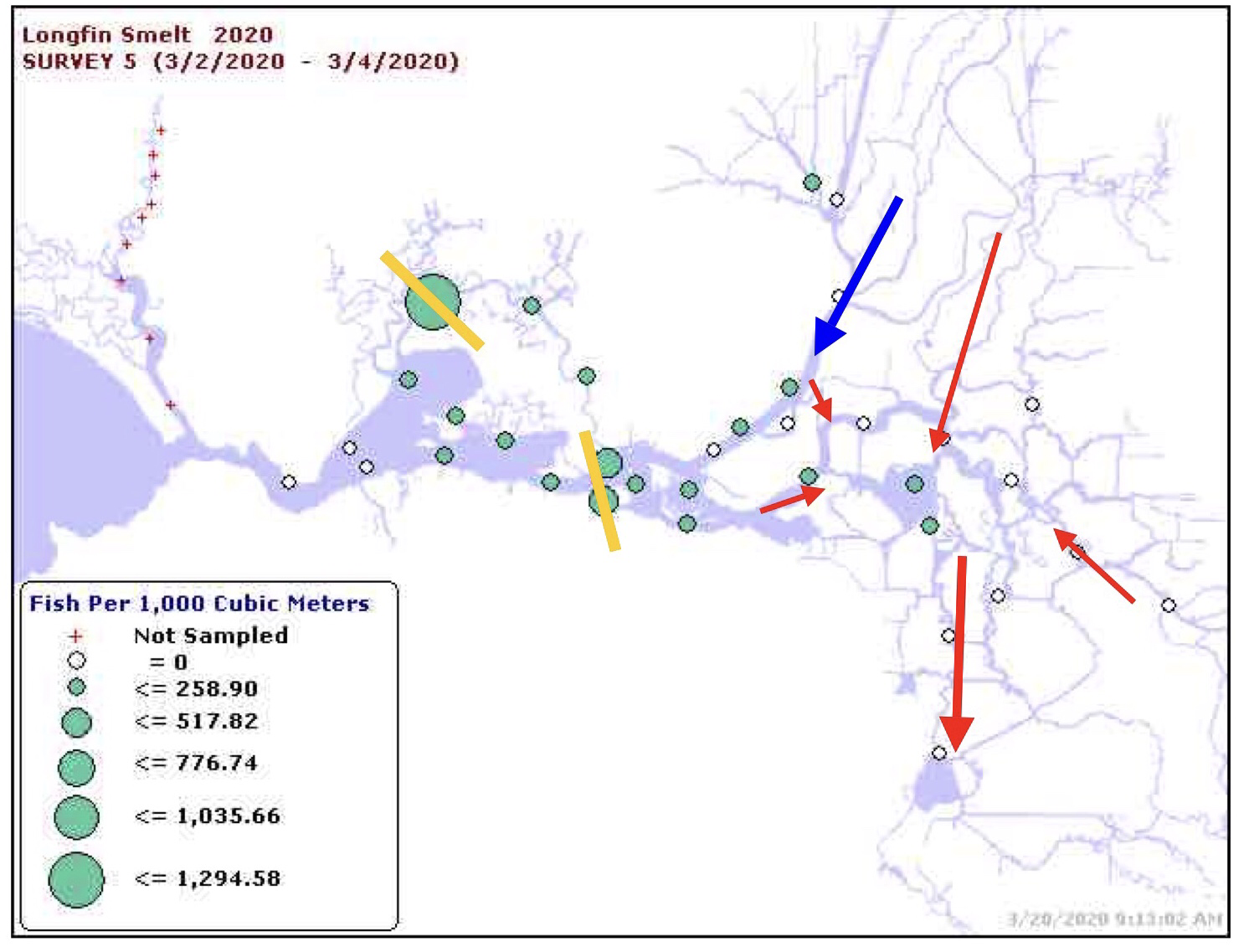

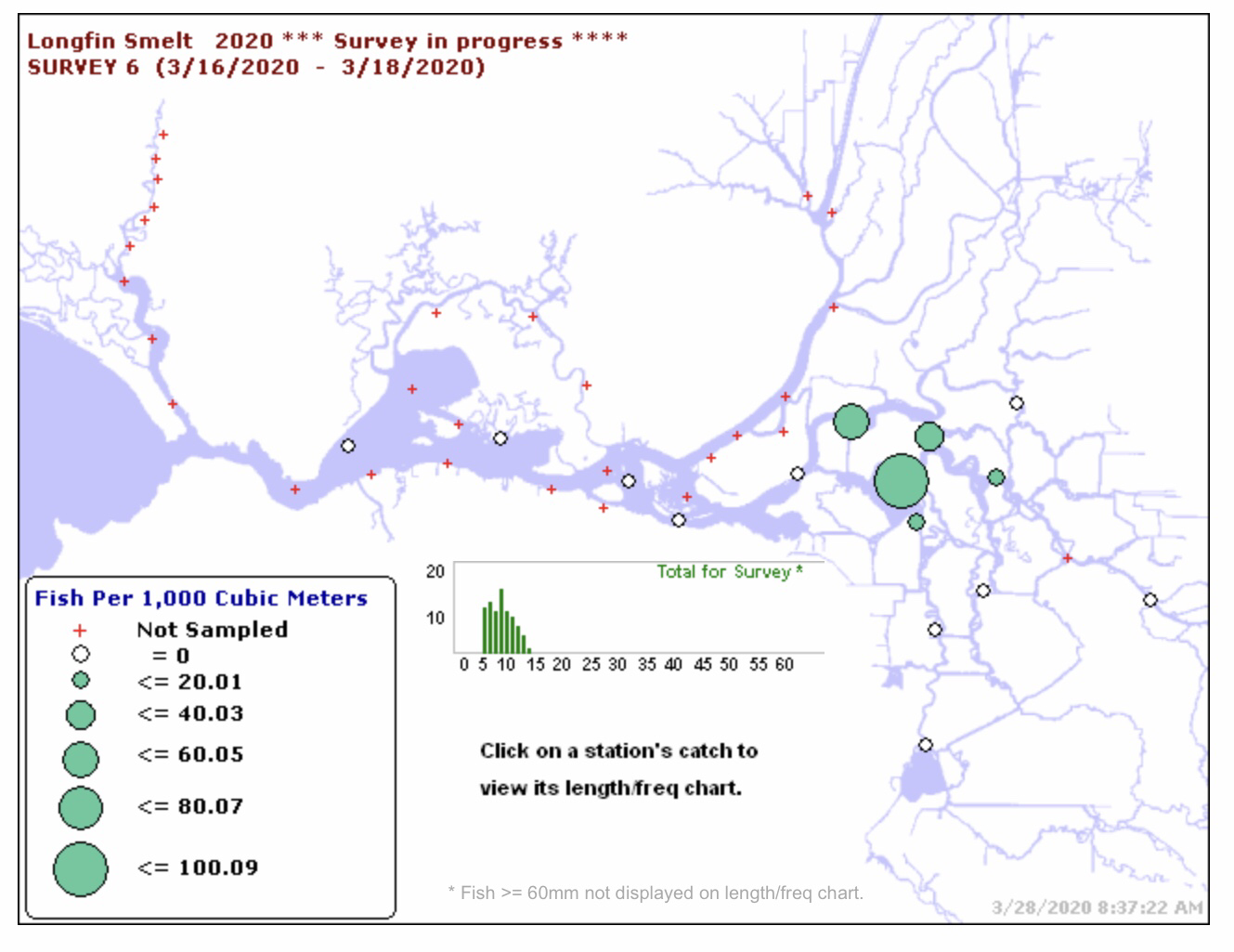

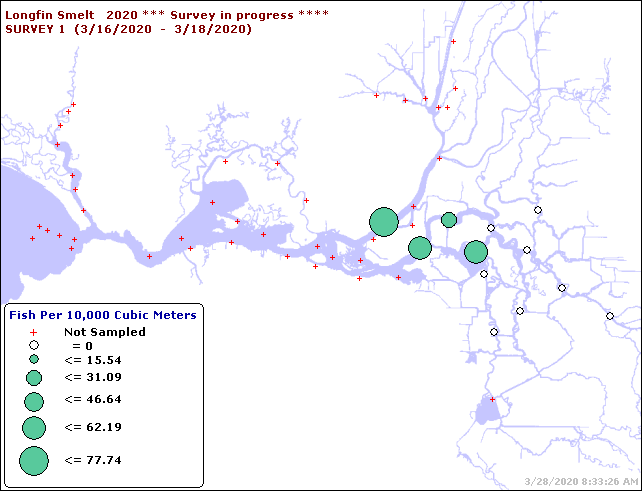

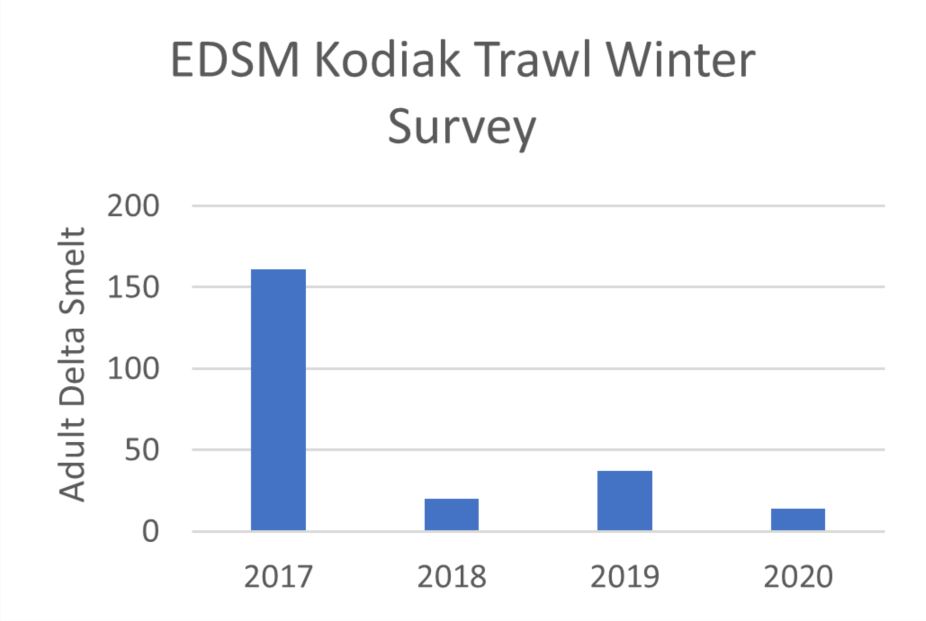

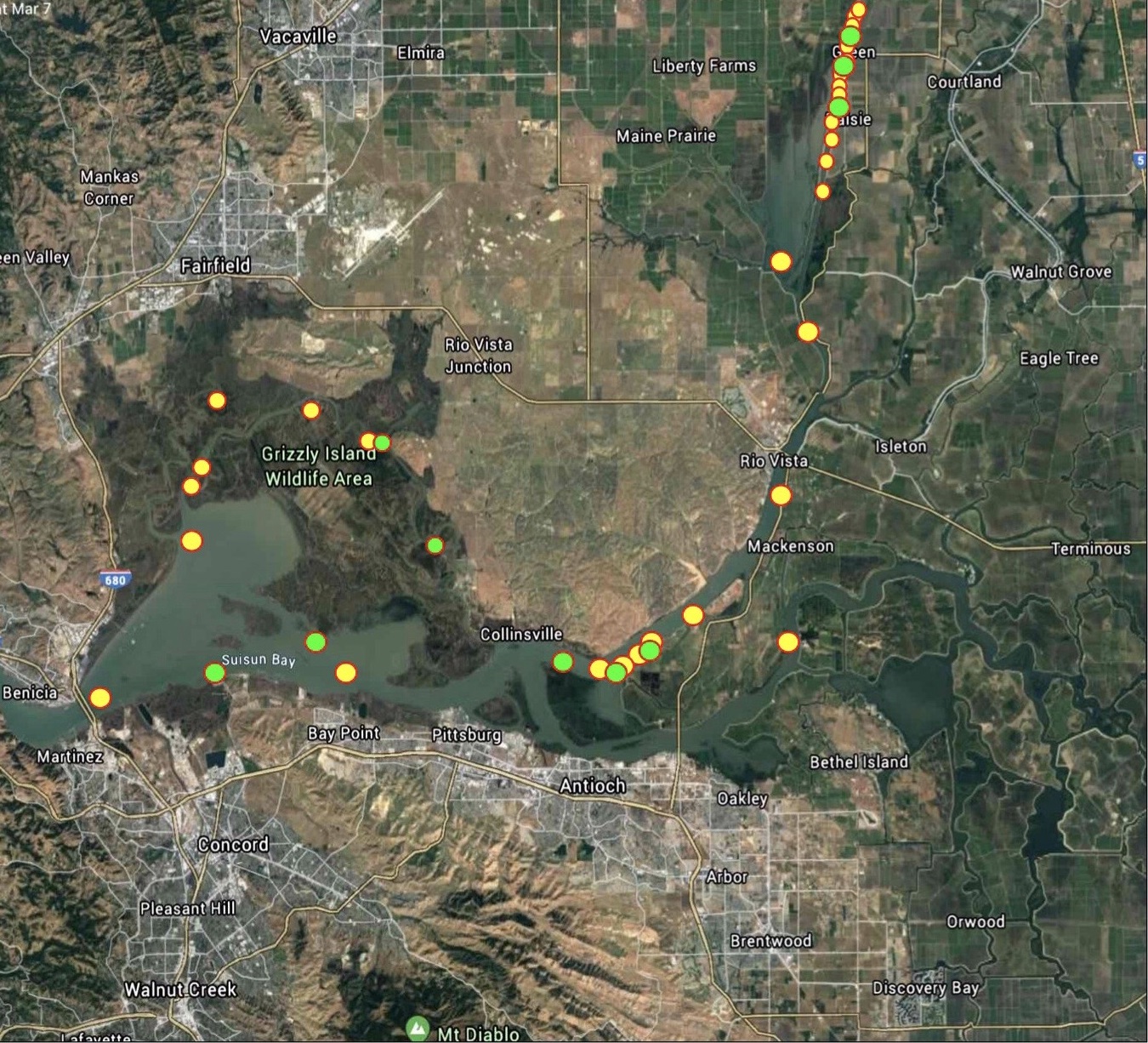

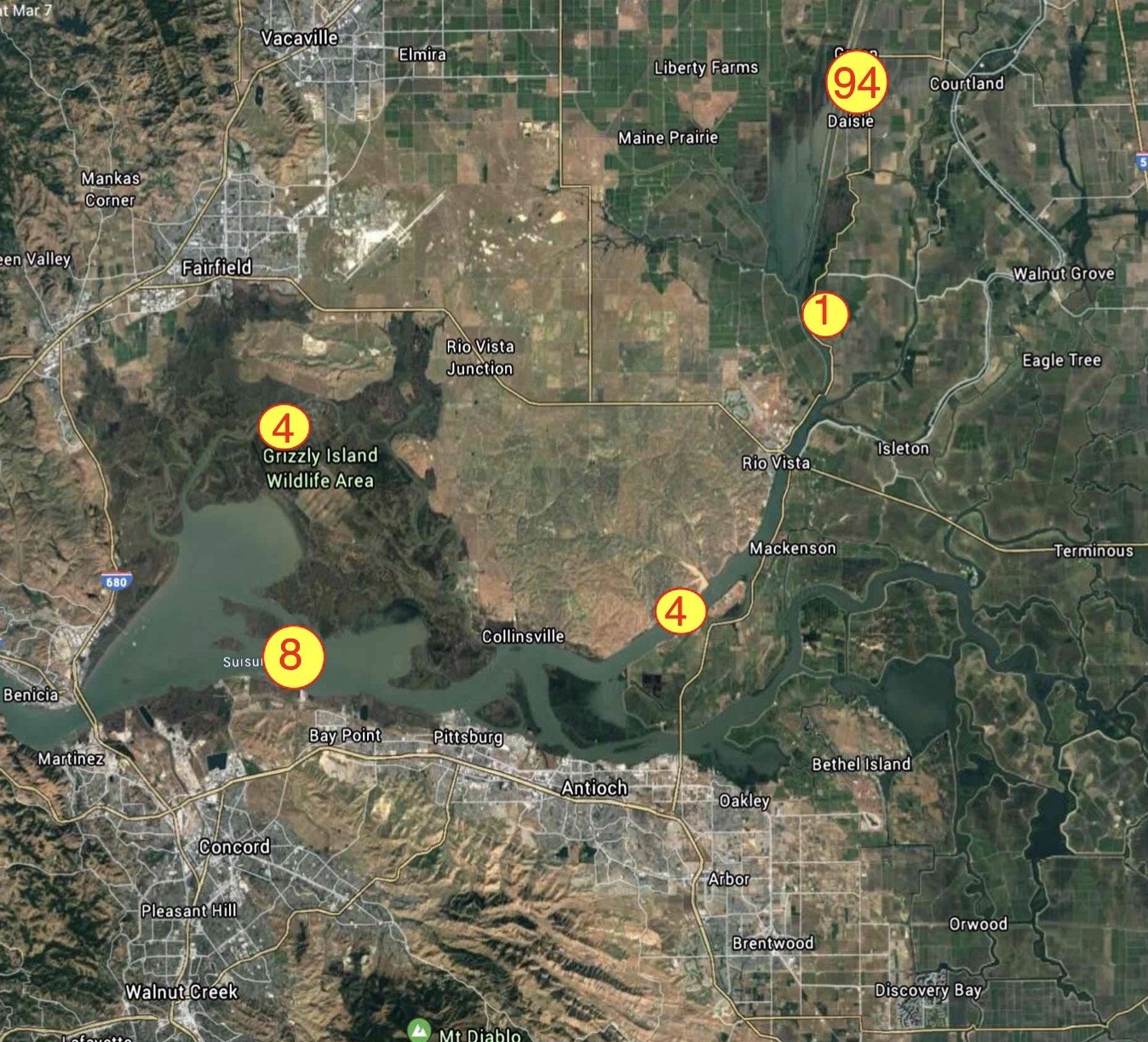

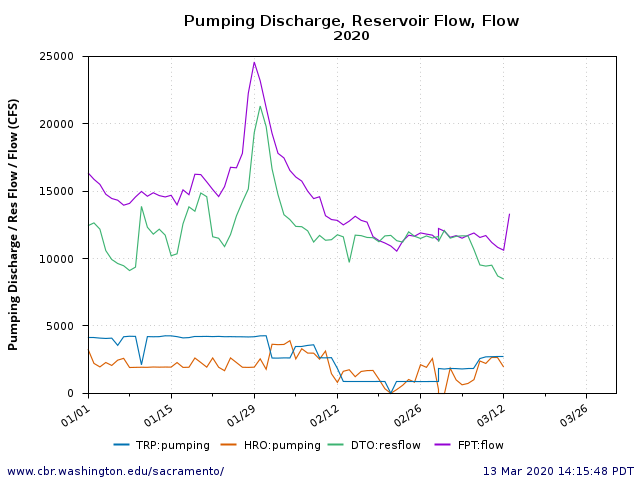

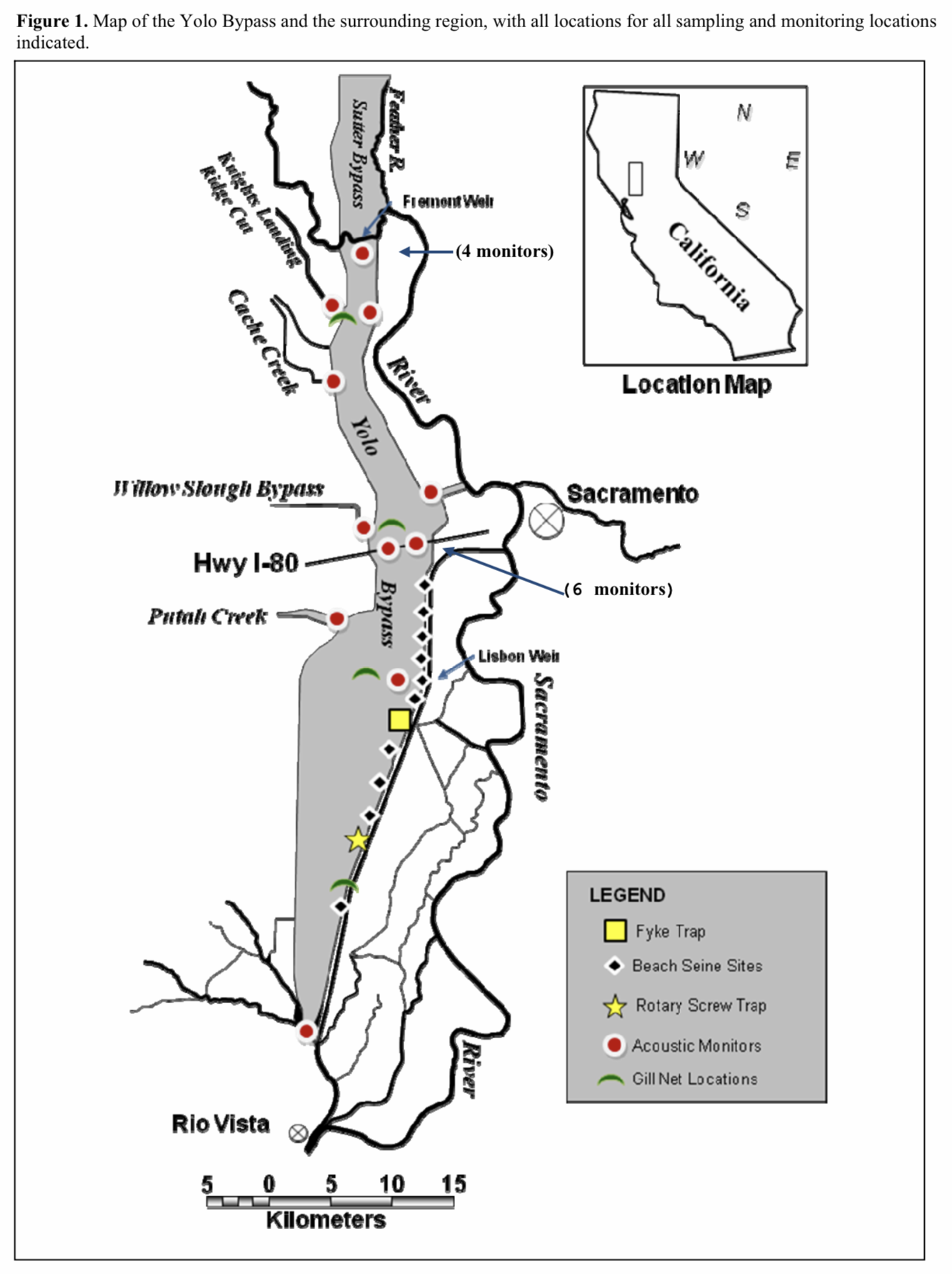

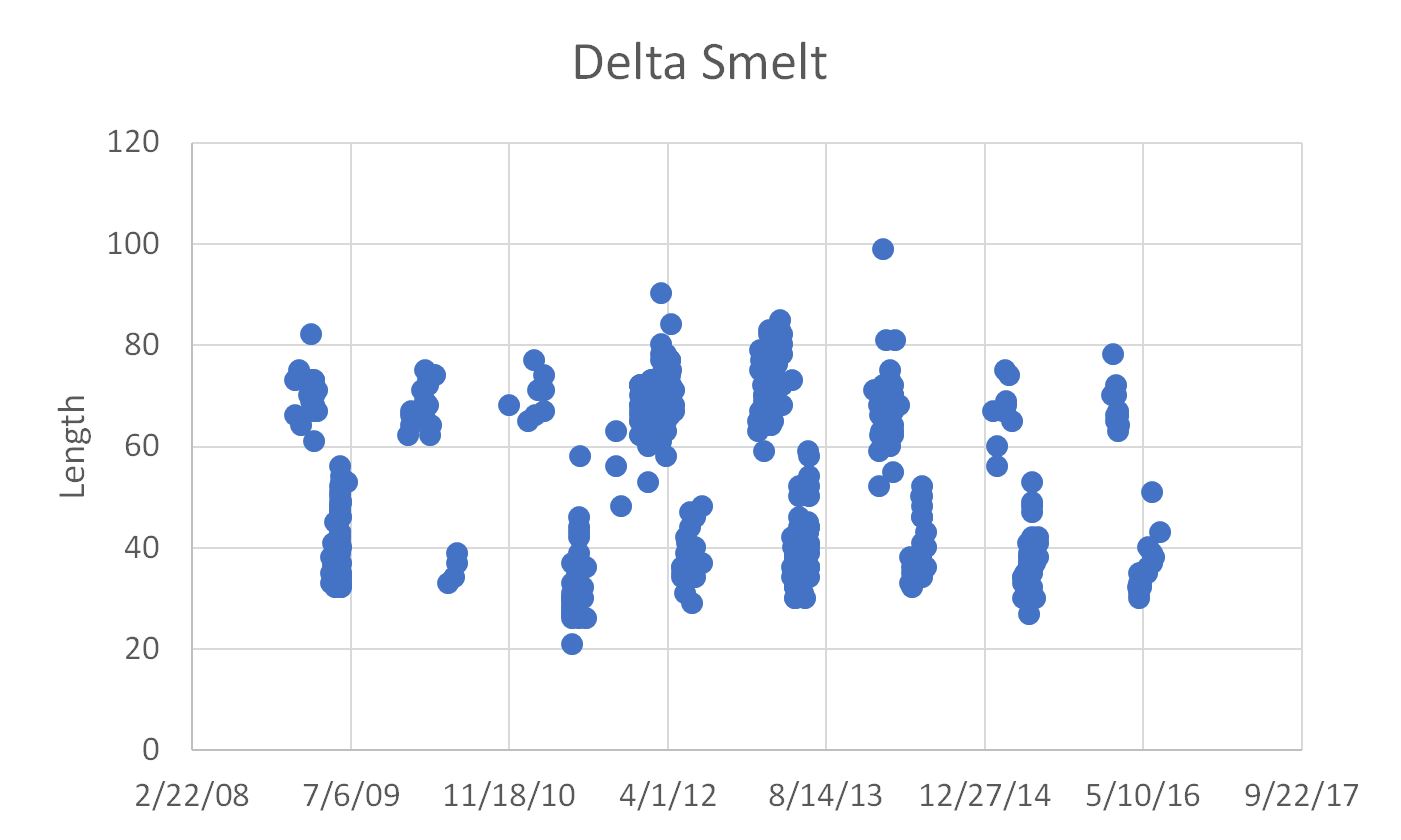

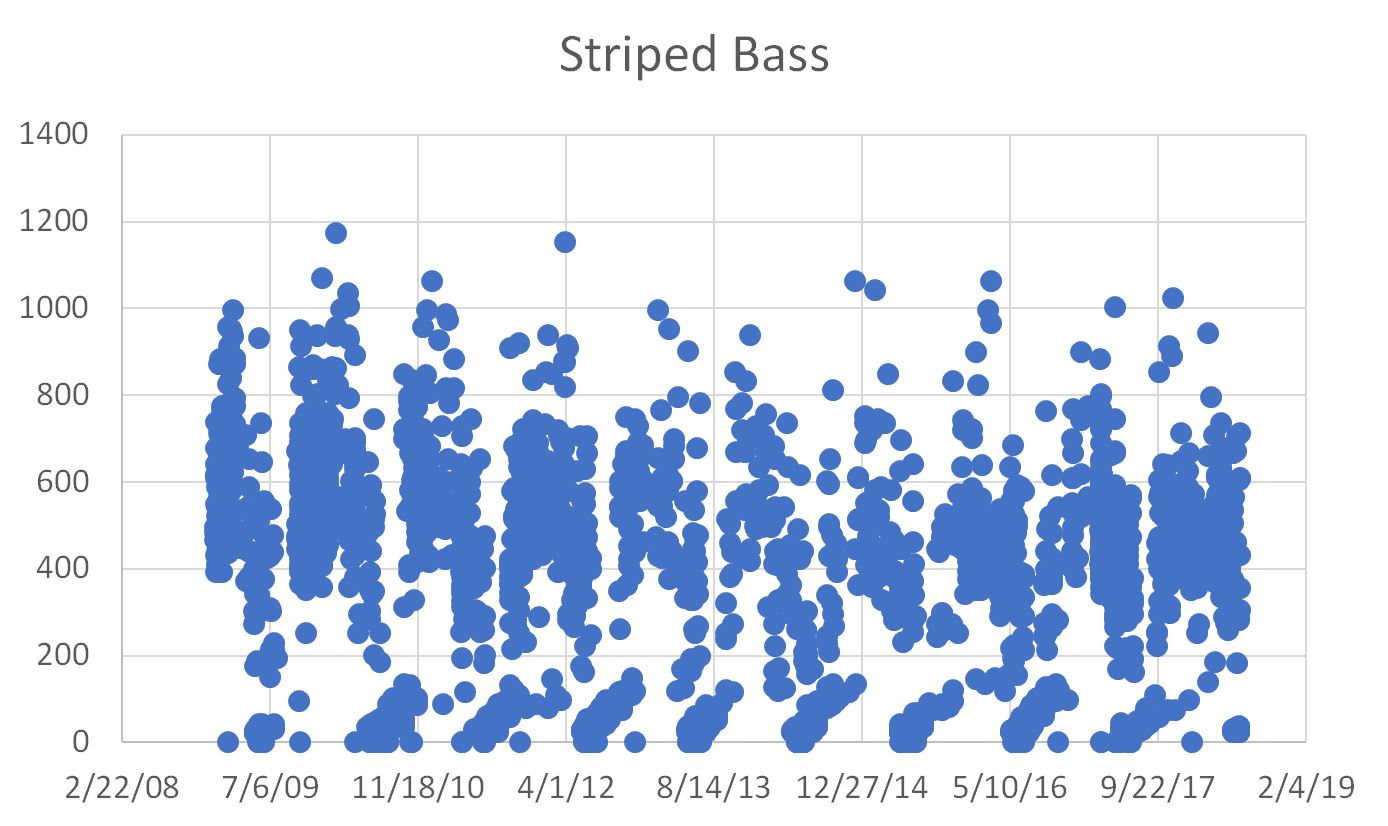

To partially address the hypothesis myself, I analyzed some Interagency Environment Program (IEP) data1 collected over the decade of 2009-2018 from one of the remaining Delta smelt strongholds – the lower Yolo Bypass portion of the Cache Slough Complex of the north Delta (Figure 1). Delta smelt were a common seasonal resident of the area (Figure 2). Striped bass, as expected, were very abundant in all age groups over much of the survey periods (Figure 3). But so were many species of invasive non-native catfish, sunfish, crappie, gobies, minnows, tule perch, black bass, and shad, most of which have been present in the Delta as long as striped bass.

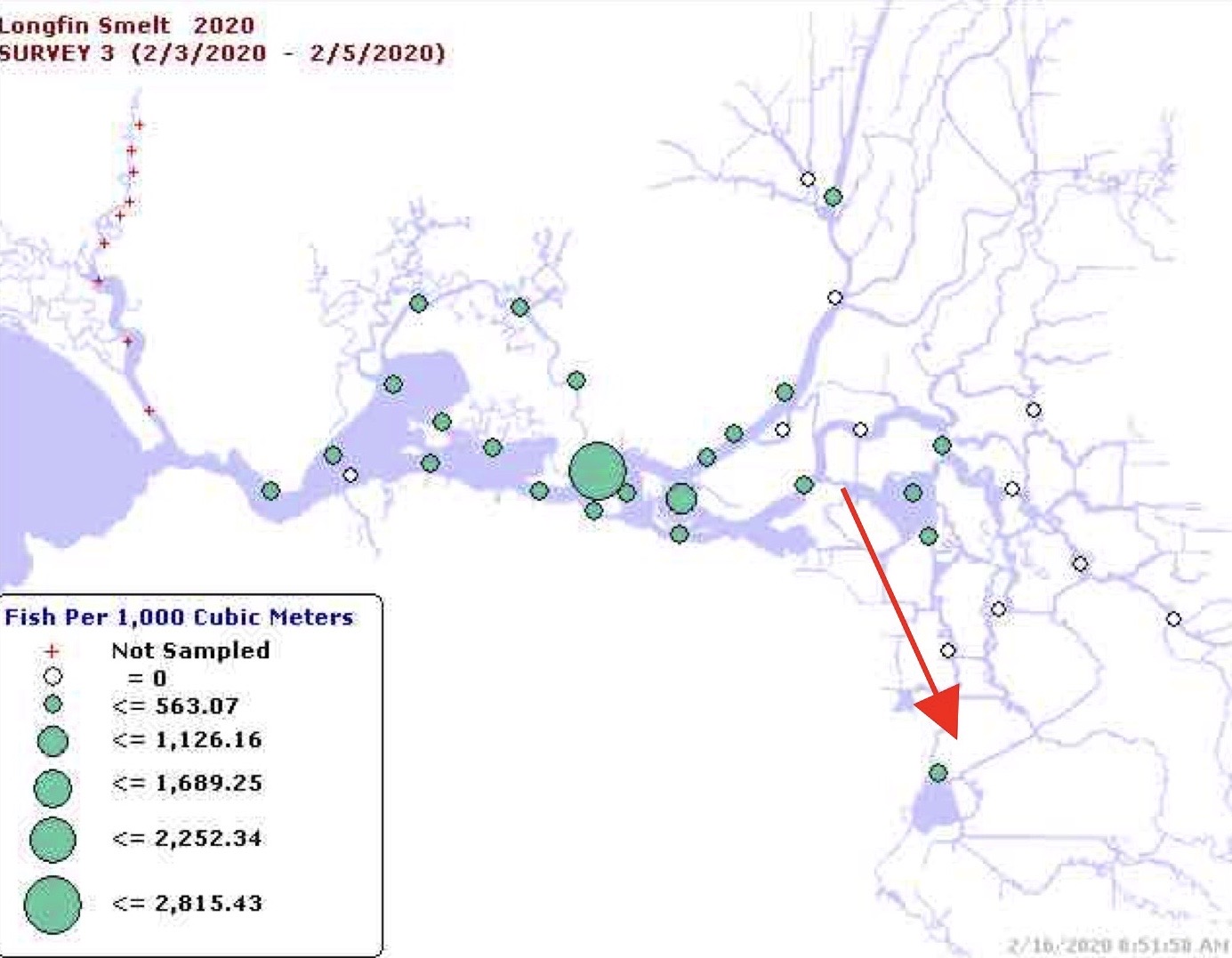

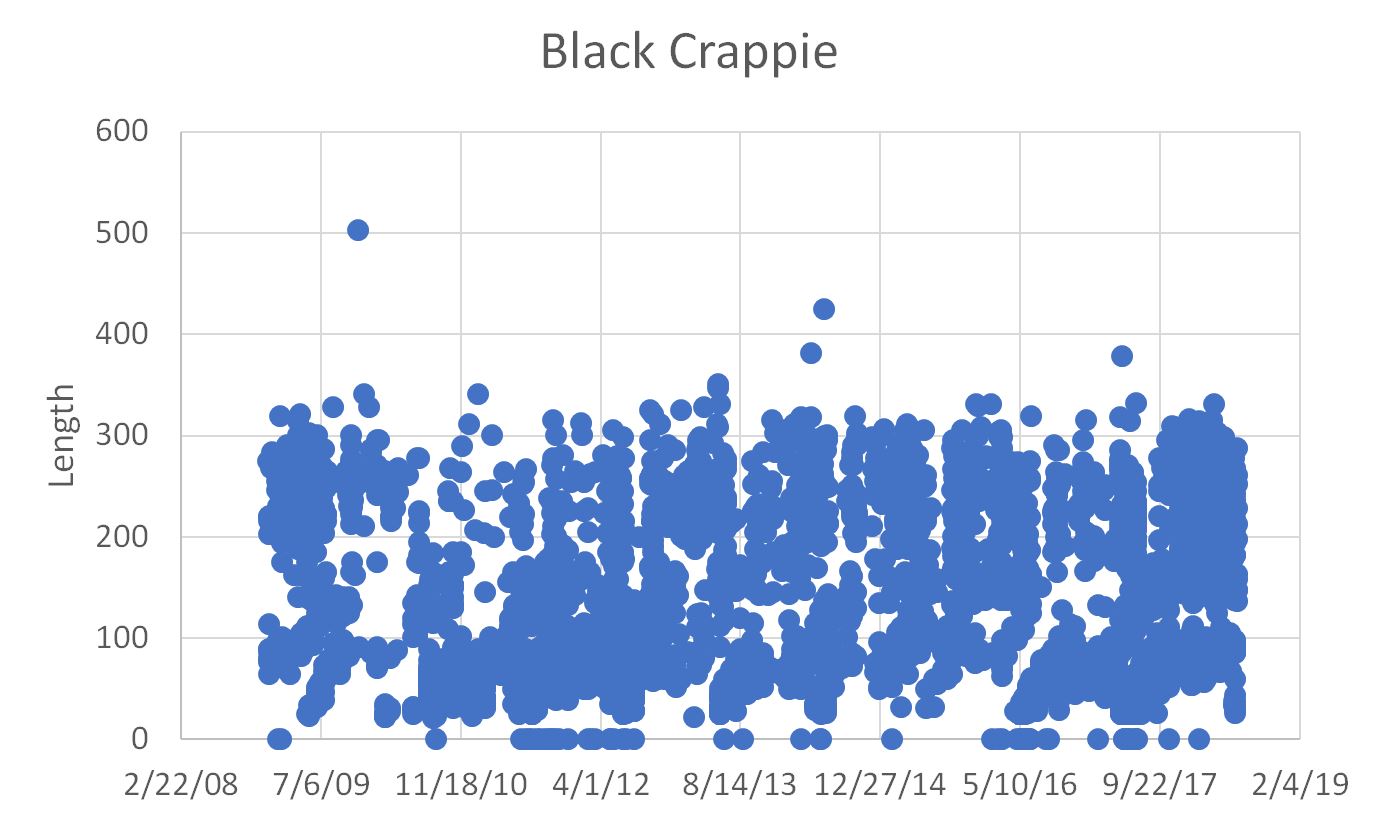

Black crappie alone make up an equivalent or greater predator force on Delta smelt (Figure 4). In addition, black crappie as well as many of the other abundant predators compete with Delta smelt for their common zooplankton food supply. Not one of these potential other sources of predation or competition is mentioned in the essay.

Nobriga and Smith do acknowledge: “A generalist predator like Striped Bass, however, could suppress Delta Smelt competitors in addition to Delta Smelt, leading to non-linear and counter-intuitive community dynamics” – a theory that once-abundant striped bass have been suppressing other non-native predators and competitors of Delta smelt. So how long has that dynamic been functioning? Was it functioning in the hypothesized epoch of “phantom” predation? Did striped bass accelerate the decline of Delta smelt or, by eating and consuming other predators, slow it down? And assuming that Delta smelt really were much more abundant than previously believed prior to widespread monitoring in the Delta, to what degree was predation a factor in that decline?

Figure 2. Lengths of Delta smelt collected in fish surveys in lower Yolo Bypass 2009-2018. Note that up to 70% of the smaller young 20-60 mm smelt were later genetically identified as Wakasagi.

Figure 3. Lengths of striped bass collected in fish surveys in lower Yolo Bypass 2009-2018.

Figure 3. Lengths of black crappie collected in fish surveys in lower Yolo Bypass 2009-2018.