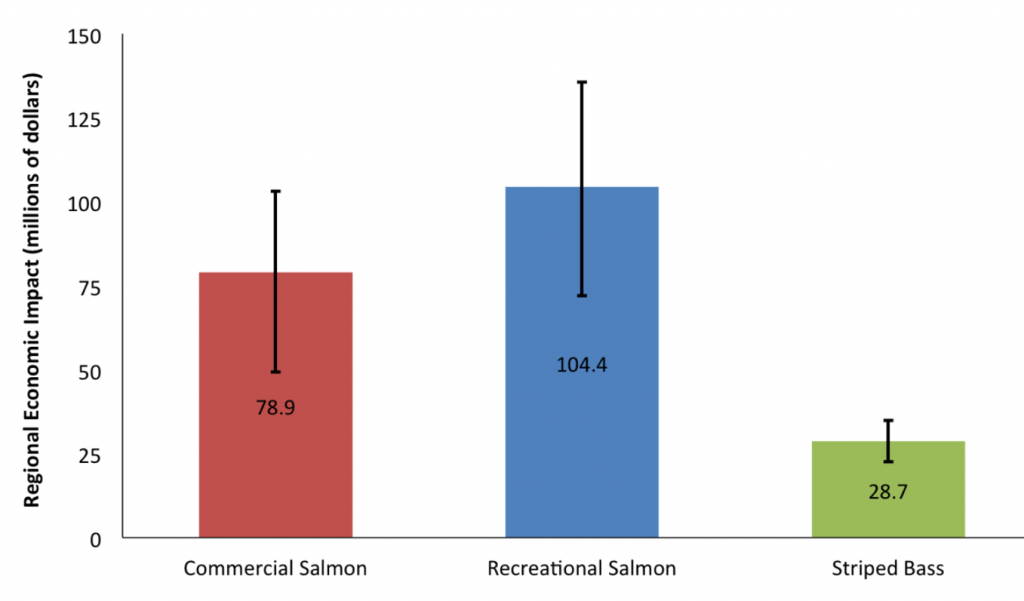

In a recent blog post1, FISHBIO again discuss the role they allege that Striped Bass are playing in limiting salmon production in the Central Valley. They bring up the 5-year-old proposal to reduce regulations on the Striped Bass fishery that was soundly rejected by fishermen, resource managers, environmentalists, and scientists alike. They state that despite the fact that anglers spend more than ten times the hours spent fishing for stripers than for salmon, the economic benefit of striper fishing is far below that of salmon fishing.

Well, assuming the raw economic numbers are true:

- The State closed the Striped Bass commercial fishery a century ago.

- The Striped Bass fishery is year-round and throughout most of the Central Valley, whereas the salmon fishery is seasonal and more localized. There must be some social value in diversity.

- The economic status of Striped Bass fishermen is far more diverse than salmon fishermen. There must be some social value in supporting a broader range of citizens.

- Many California residents are from the East, where stripers are king and there are no salmon.

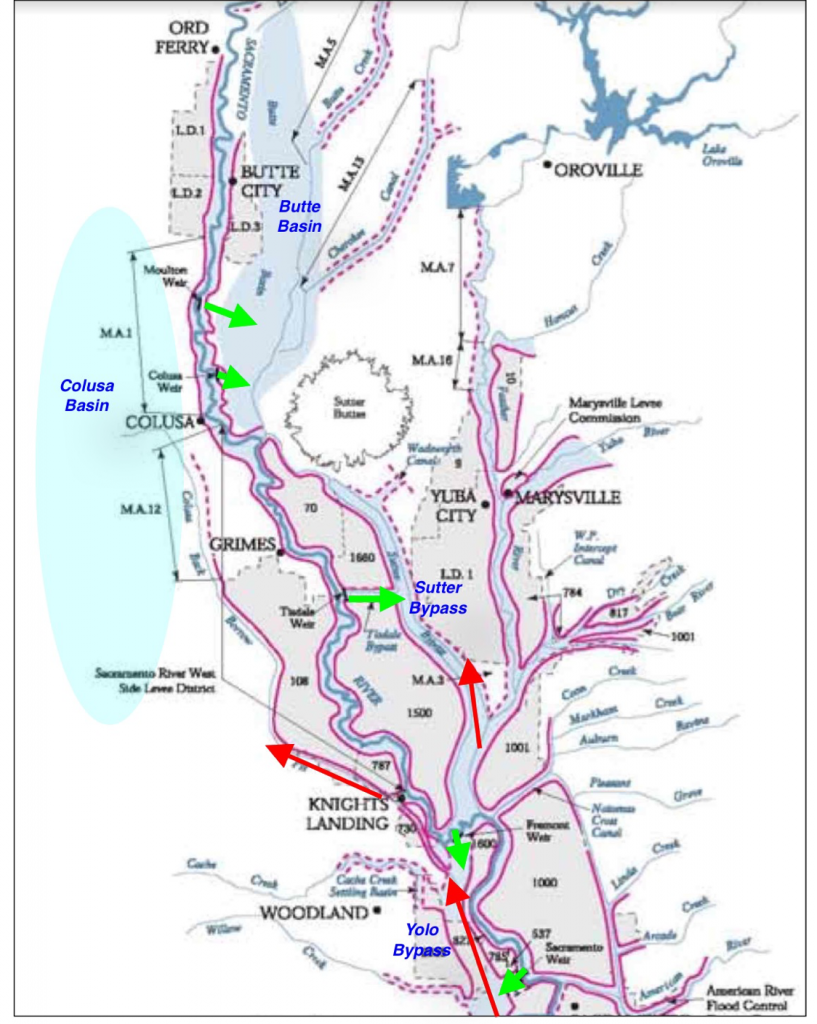

- Much of the salmon fishery value derives from the ocean fisheries, whereas the striper fishery is focused on Bay-Delta and inland waters. The relative cost of fishing in these regions is very different.

- Most of the salmon fishery value (over 90%) is derived from hatchery fish. The Striped Bass supplemental rearing program was closed over a decade ago. The striper effort was ten times higher then, the number of stripers was up to ten times higher in the past, and the economic value was also likely ten times higher.

The other portion of FISBIO’s argument concerns the role of Striped Bass predation in salmon declines.

- “ During the early 1900s, striped bass thrived alongside salmon, but as salmon declined over the latter part of the century, the impact of these introduced predators took a proportionally greater toll on the salmon population.” There is no evidence to support this statement. Stripers have declined more than salmon. There are still 30-million hatchery smolts for a much smaller striper population to feed on.

- “Controlling predators to help their prey species is not a new idea; other states have been controlling non-native and native predators with measured success for decades.” No doubt the greatest “predator control” success (over 90%) has been on the Striped Bass population by the federal and state export pumps over the past two decades.

- “While California has failed to act, some political support for predator control has recently developed at the federal level. Multiple bills currently proposed in Congress include provisions for advancing predator control in the Delta.” These bills were sponsored by San Joaquin Valley congressmen and have little chance of passing.

- “While these federal actions alone may not be sufficient to produce population increases in some threatened or endangered species, there is evidence that predation is a major barrier to salmon recovery, and the proposed legislation demonstrates a changing mindset toward controlling predation of declining species.” There is no evidence that predation by Striped Bass on wild threatened salmon runs is even in the top ten reasons for their declines. The “mindset change” is to divert attention away from the real reasons for threatened salmon declines, or from having to pay for their recovery.

Finally FISHBIO speaks to “changing mindsets” of anglers: “Perhaps the biggest hurdle to controlling non-native species like striped bass will be changing the mindset of the fishing community that cares deeply about these popular predators.” They mean that anglers should accept the false premise that Striped Bass are the problem and should allow them to be exterminated.