The Bay-Delta Science Conference held this past November focused on the topic of “Science for Solutions: Linking Data and Decisions”. There were a diversity of subjects and presentations on the topic. A special series of papers previewed the conference presentations in the San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science (UC Davis). The conference presentations and journal articles were a lot to take in.

The Bay-Delta Science Conference held this past November focused on the topic of “Science for Solutions: Linking Data and Decisions”. There were a diversity of subjects and presentations on the topic. A special series of papers previewed the conference presentations in the San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science (UC Davis). The conference presentations and journal articles were a lot to take in.

My take on the conference and associated journal articles is that they represent a continuation of a decades-long attempt to avoid and direct focus away from the root cause of the Bay-Delta ecosystem’s greatest problems: high Delta exports, low river flows to the Delta, and low Delta outflows to the Bay under past and present water management. Simply put, there was a lot of the “same-old, same-old” mix of perspectives (excuses), with some new and interesting science.

A previous post covered the conference paper on Delta smelt. Another covered introductory presentations. In this post I focus on one presentation and paper entitled Perspectives on Bay-Delta Science and Policy, a summary of the conference prepared by its sponsor’s (the Delta Stewardship Council) Independent Science Board.

PERSPECTIVES

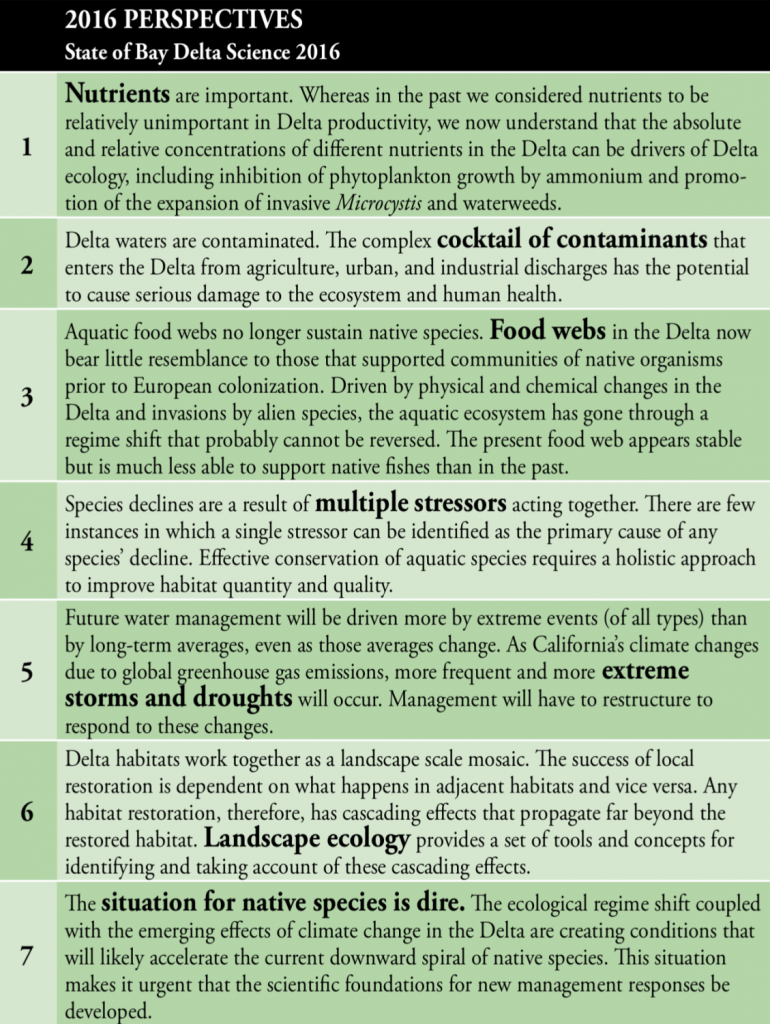

“Perspectives” focuses on seven themes the Independent Science Board has grown to accept as the causes of the Bay-Delta problems (Figure 1):

- Nutrients – Changes in and lack of nutrients are now considered important.

- Contaminants – Delta waters are now considered contaminated.

- Food Webs – Much less able to support fish than in the past.

- Multiple Stressors – Multiple stressors work together to cause the decline in Delta native fishes.

- Storms and Droughts Extremes – Extremes in drought and floods wreck havoc on water management.

- Landscape Ecology – Restoration has not been pursued on a landscape scale.

- Dire Straits of Endangered Species – Regime shifts and climate change have contributed to accelerated spiraling declines in native fishes.

Even if the underlying science on the subjects (factors) is valid, the arguments that relate these factors to the Bay-Delta ecosystem decline are not. At most, these factors are secondary actors in the overall process driven primarily by water management, Central Valley and Bay-Delta water quality standards, and endangered fish “protections in biological opinions.

The focus on these perspectives represents an overall intent to misinform and misdirect science and management away from real causes and effects, and from effective solutions to the Delta’s problems. Some topic examples:

- “In the past we considered nutrients to be relatively unimportant in Delta productivity.” Untrue. The loss of nutrients that went along with water quality improvement over the past half century were always a concern. Sewage treatment upgrades were considered a factor in declines in Delta fish production. Aerial fertilization of the Delta was considered at least two decades ago.

- “The low salinity zone, once a food-rich region of the Delta, now provides little food for native fish.” This statement is untrue. The LSZ remains the key rearing area of the Central Valley for smelt, salmon, sturgeon, and splittail, because it has the highest concentrations of “food” in the Bay-Delta Estuary.

- “Aquatic food webs no longer sustain native fishes.” Untrue. Native fish are sustained if given a chance. Smelt and salmon were nearly recovered in 2000 after six wet years and massive recovery efforts and new protections. The protections simply failed to carry over into dry sequences 01-05, 07-10, and 12-16. Poor food, growth, and survival are caused by man-made drought conditions, and lack of protections of the pelagic food web of the Bay-Delta in drier years.

- “There are few instances in which a single stressor can be identified as the primary cause of any species’ declines.” Untrue. River flow and exports are often the single most important factors in single events, such as winter-run salmon year-class failures below Shasta.

- “Effective conservation requires a holistic approach.” Yes, one that does not take most of the fresh water from the rivers, Delta, and Bay.

- “The aquatic ecosystem has gone through a regime shift that cannot be reversed.” Untrue. Taking most of the water out of the estuary from late winter through fall every year keeps the aquatic ecosystem in a semi-permanent drought, broken only by wet water years when large amounts of unregulated water escape capture by water managers. The patterns of the 2010-2011 water years show that negative patterns can be reversed.

- “The problems have been caused by invasive clam and aquatic plants, and other non-native animals of the Bay-Delta foodweb.” Untrue. These are for the most part secondary responses to the real cause: greater exports and low river flows.

- “More frequent and extreme storms and droughts will occur.” Four of last five, seven of last ten, and ten of last sixteen years have been part of drought sequences. From 1987 through 1996, seven of ten years were drought years. Water year 2017, though extreme, is not unlike previous very wet years.

- “Habitat restoration has cascading effects.” In truth, restoration has as yet been minimal, with minimal evidence that it contributes substantial beneficial effects.

- “The ecological regime shift and climate change are accelerating decline of native species.” While climate change certainly is not helping, the declines of native species are for the most part avoidable by reducing demands on water. The most important “regime shifts” of the last several decades have been shifts in water management strategies.

FORWARD-THINKING ACTIONS

The Independent Science Board’s editorial board extracted the following forward-thinking actions from their 2016 Perspectives paper:

- Incorporate long-range (50 year) thinking into Delta science and management. Acknowledge the accelerating rates of change ahead, and the inability to return to past conditions, in evaluating and planning feasible options for the future. Long-term planning is generally a good idea, but this formulation ignores current reality and the need to (1) return to past levels of protection, and (2) be wary of water management strategies that would further undermine the Bay-Delta ecosystem.

- Incorporate more exploratory and forward-looking science into government science programs at all levels, including science not tied to any current policy or crisis. Start planning now for about 15% of the overall Delta science budget to transition into more forward-thinking science. More science is not the answer. More science is more smoke.

- Widen science career paths in state agencies so that scientists are not forced to abandon science to advance their careers. More scientists are needed in management to apply the science that is already available.

- Plan for variability and extremes in the decades ahead, as well as long-term change. Bolster the ecosystem’s capacity to absorb both drought and deluge by continuing to reduce the state’s demand for water supply from the Delta, as required by the Delta Reform Act of 2009. Replenish Central Valley groundwater reservoirs and promote agricultural practices more resilient to drought. Adjust water management practices to accommodate less predictable sources of supply and more variable flows. Sound advice.

- Adapt management practices to take advantage of any ecological, recreational, and economic values to be gained. Yes, take advantage of low cost, high benefit practices.

- Begin the scientific and societal groundwork needed to seriously explore alternatives to conservation in place for endangered species. Continue all reasonable efforts to provide for them, including reducing water demand on the Delta, but recognize that the time has come to develop the science and policy foundations for more radical approaches, including assisted relocation, assisted evolution, and cryopreservation. There is also a need to enhance and build conservation hatcheries. But most of all, we need to protect and enhance the resources we have left.

- Invest now to develop models of the Delta system, analogous to global climate models, that more fully integrate physical, ecological, and social sciences. Use these models to forecast likely outcomes from changing climate and other external forces acting on the Delta, as well as likely effects of various management policies. Math models of complex ecosystem function are unnecessary – simpler conceptual and statistical (data) models are more realistic and better management tools.

- Weave “Delta as an Evolving Place” into all science, planning and management programs. Stop allowing further “evolving” and start de-volving where reasonable. The Bay-Delta is not really evolving; it is just ever-increasingly being disturbed.

Rethinking the above perspectives and actions would be a reasonable first step toward a more progressive strategy for the Delta Science Board.

Figure 1. Perspectives on Bay-Delta Science and Policy. (Independent Science Board)