Video Screen Grab of lower Jenny Creek ASSISTED SEDIMENT EVACUATION PROJECT

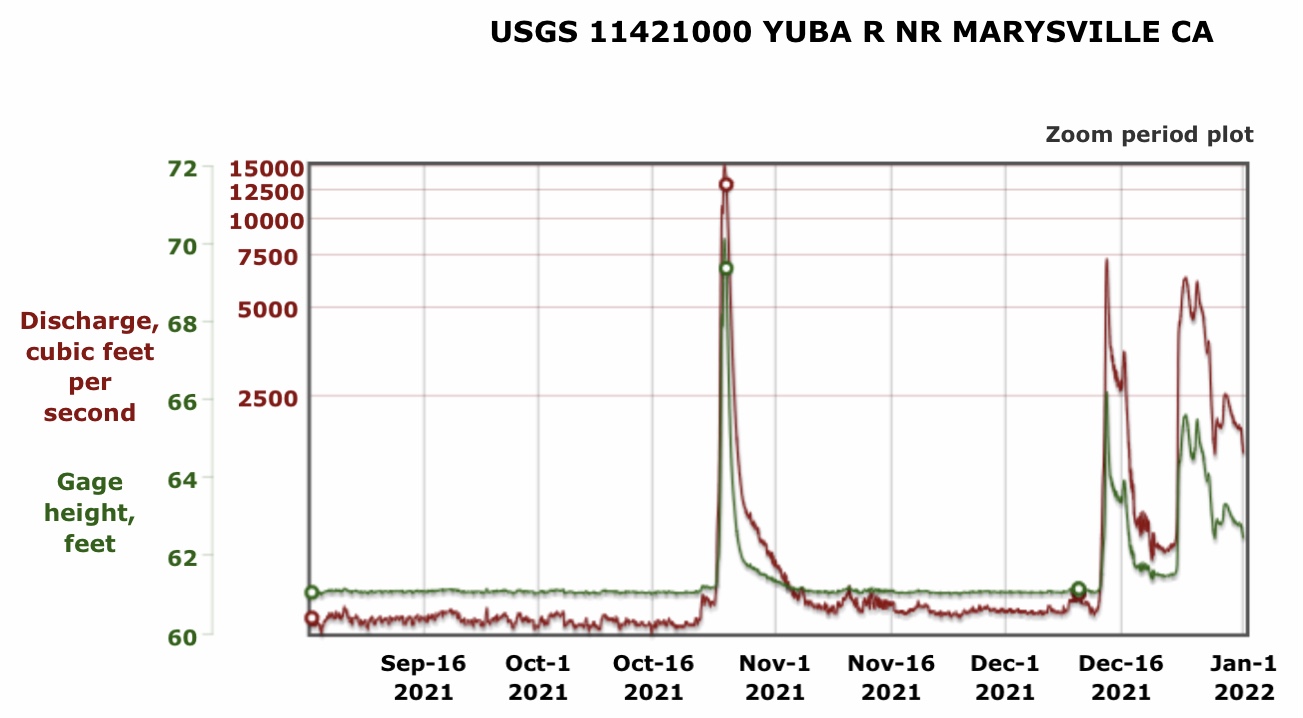

In a March 20 post, I related events in the Jan-Feb 2024 period of the Klamath Dam Removal Project. The initial four-reservoir drawdown in January led to abrupt increases in streamflow, suspended sediment, and low dissolved oxygen levels above and below Iron Gate Reservoir (the lower reservoir). This was followed by lower stable streamflow, high dissolved oxygen, and declining suspended sediment. Streamflow pulses from upstream Klamath Lake in late February and early March resulted in (short-term) elevated suspended sediment from exposed sediment erosion in the four reservoir reaches. These circumstances were expected as part of the four Dam Removal Project.

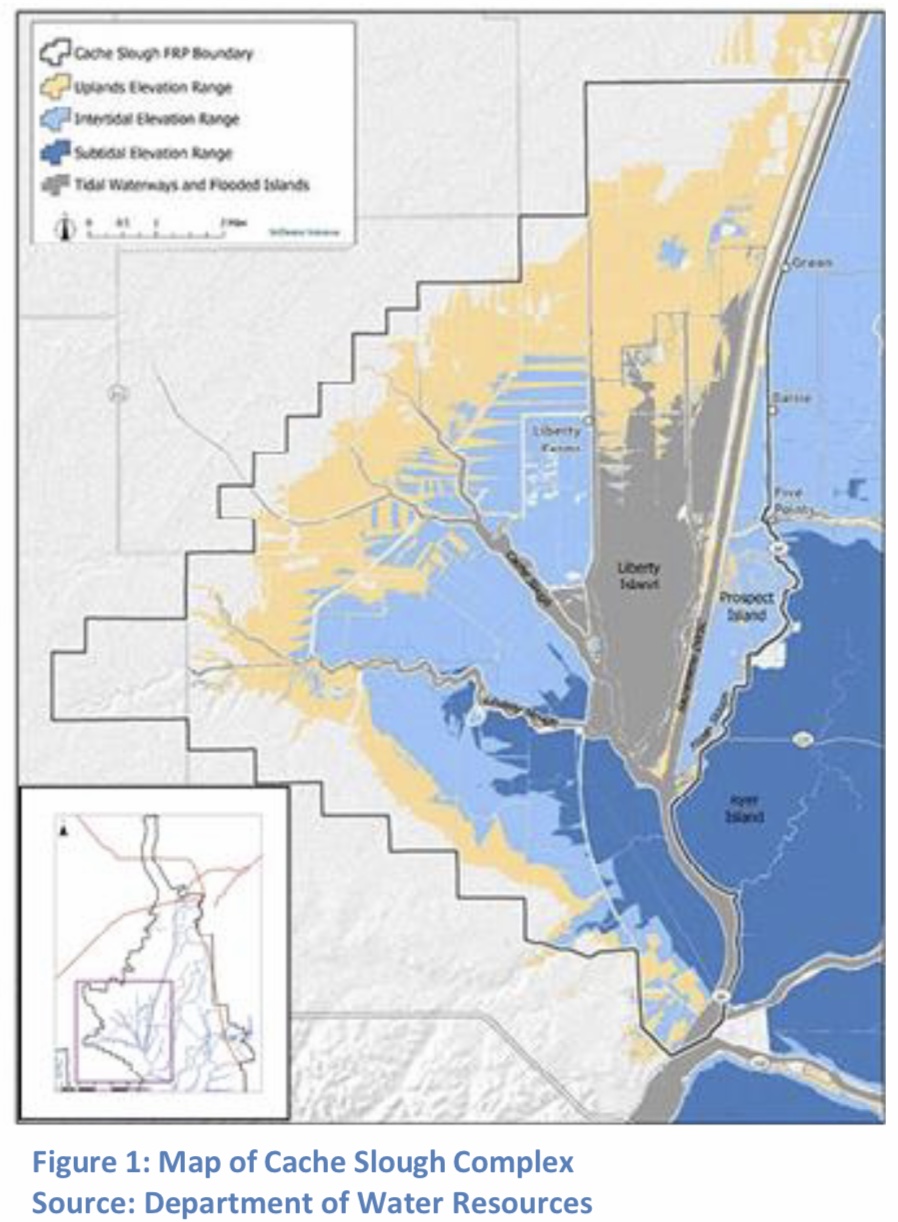

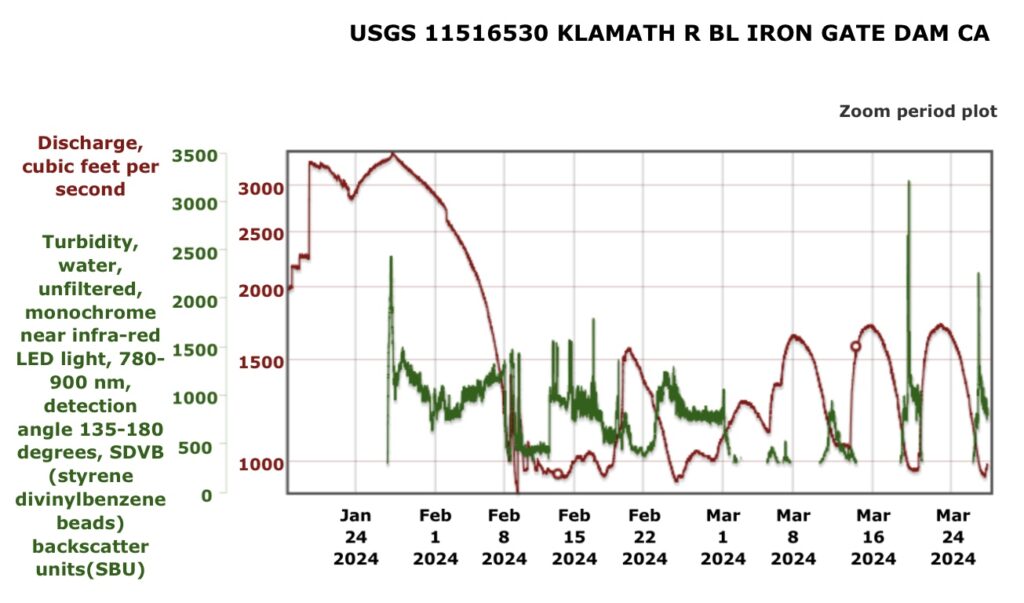

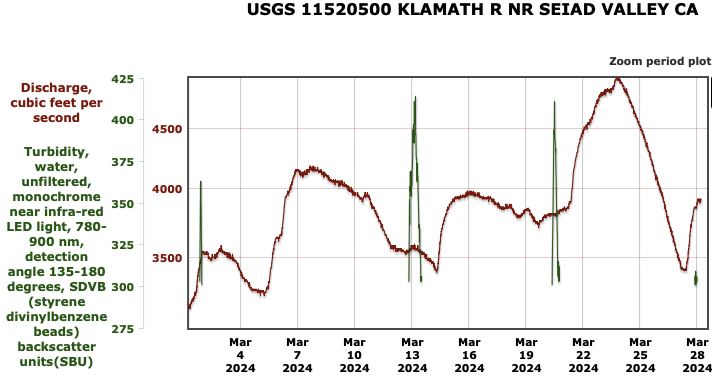

In March, the Assisted Sediment Evacuation Project began in the Jenny Creek floodplain of the Iron Gate Reservoir footprint. That project has led to lethal doses of suspended sediment (turbidity) in the lower Klamath River below the Iron Gate Dam site (Figures 1-3). Project approvals, such as the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) biological opinion quoted below, included provisions to stabilize sediments after the January drawdown, but not to flush sediments into creeks and the Klamath River.

Post drawdown and dam removal, crews will be working to actively restore the exposed reservoir footprints and tributary mouths that flow into the former reservoirs. To reduce elevated suspended sediment concentrations (SSCs), the Renewal Corporation will take active measures to flush sediment from the reservoirs during drawdown and then immediately begin stabilizing remaining sediment after drawdown has been completed. Revegetation, channel construction, and placement of habitat features such as logs and boulders will minimize erosion and allow passable channels to form in preparation of fish presence. (NMFS Biological Opinion p. 14)

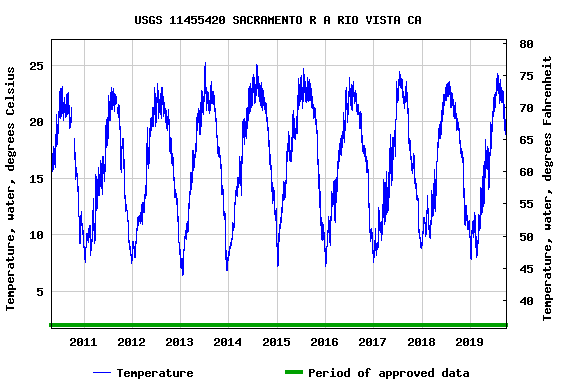

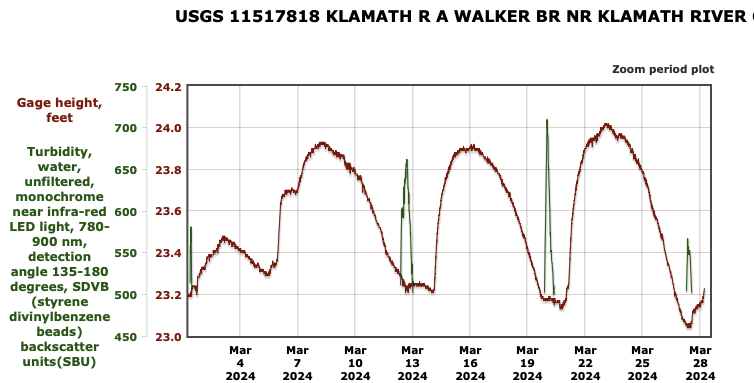

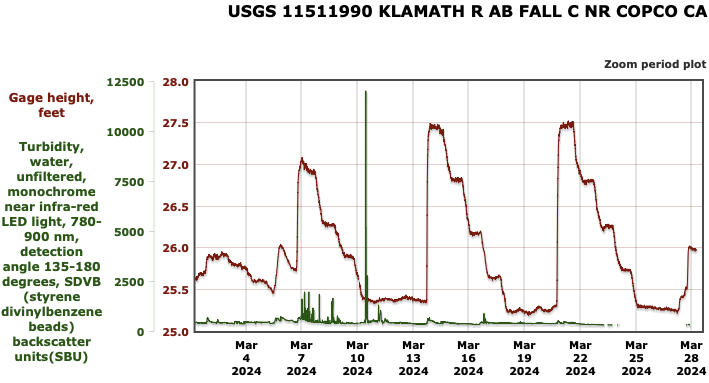

The origin of the high suspended sediment levels was likely from the exposed bed of Iron Gate Reservoir (particularly the Jenny Creek arm), not upstream reservoir erosion during the Klamath Lake flow pulses. Sediment levels below Iron Gate Dam were low during the flow pulse that diluted the high sediment loads from Iron Gate Reservoir (Figure 1). Gages below Copco and JC Boyle reservoirs were lower, generally below lethal levels (Figure 4).

Chinook salmon fry are abundant and most prevalent in the lower Klamath River below Iron Gate Dam in late winter (February-March). Coho and steelhead fry are more abundant later during spring.

The Assisted Sediment Evacuation Project is slated to end on April 15. I recommend that it cease immediately, with efforts shifted to “stabilizing remaining sediment,” in order to minimize impacts of the project on Klamath River salmon and steelhead.

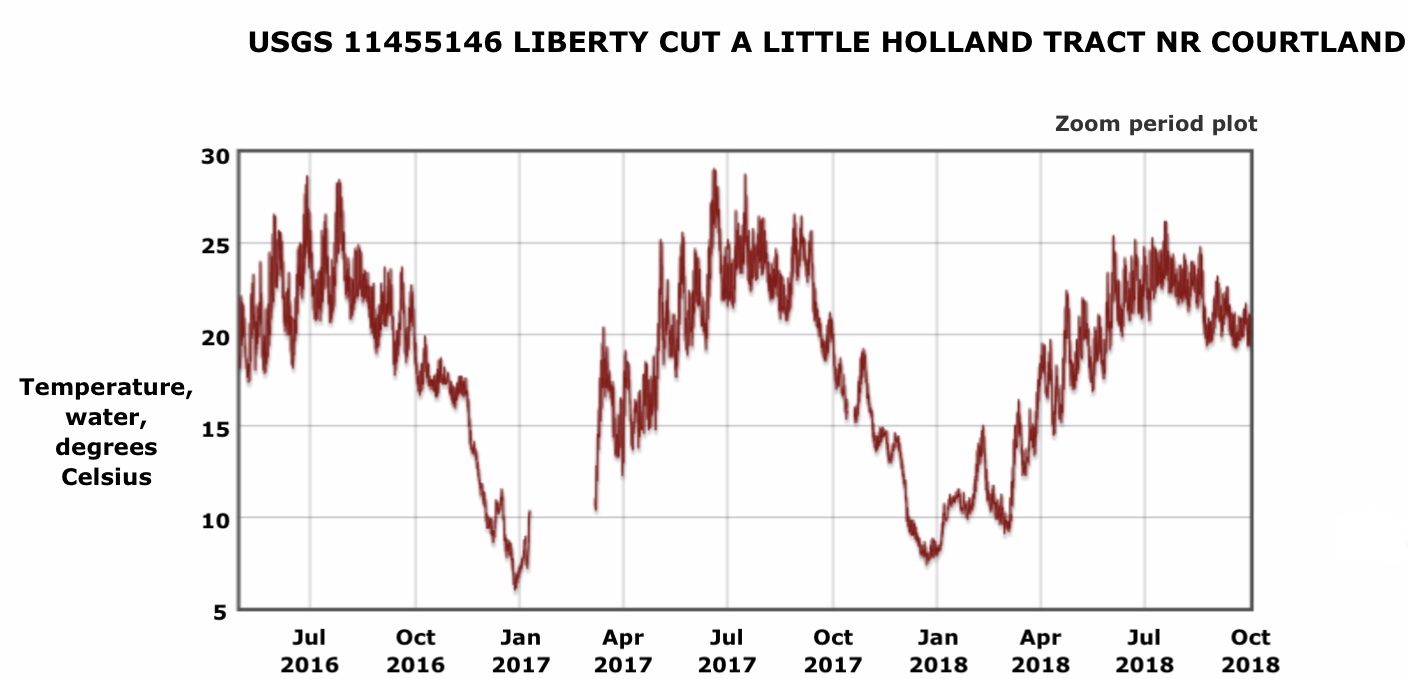

Figure 1. Turbidity and streamflow in the Klamath River below Iron Gate Dam (rm 193) in January to March 2024. Note turbidity of 300-500 SBU is roughly 1000-2000 mg/l total suspended sediment (TSS). Such levels are considered lethal for juvenile salmon and steelhead.

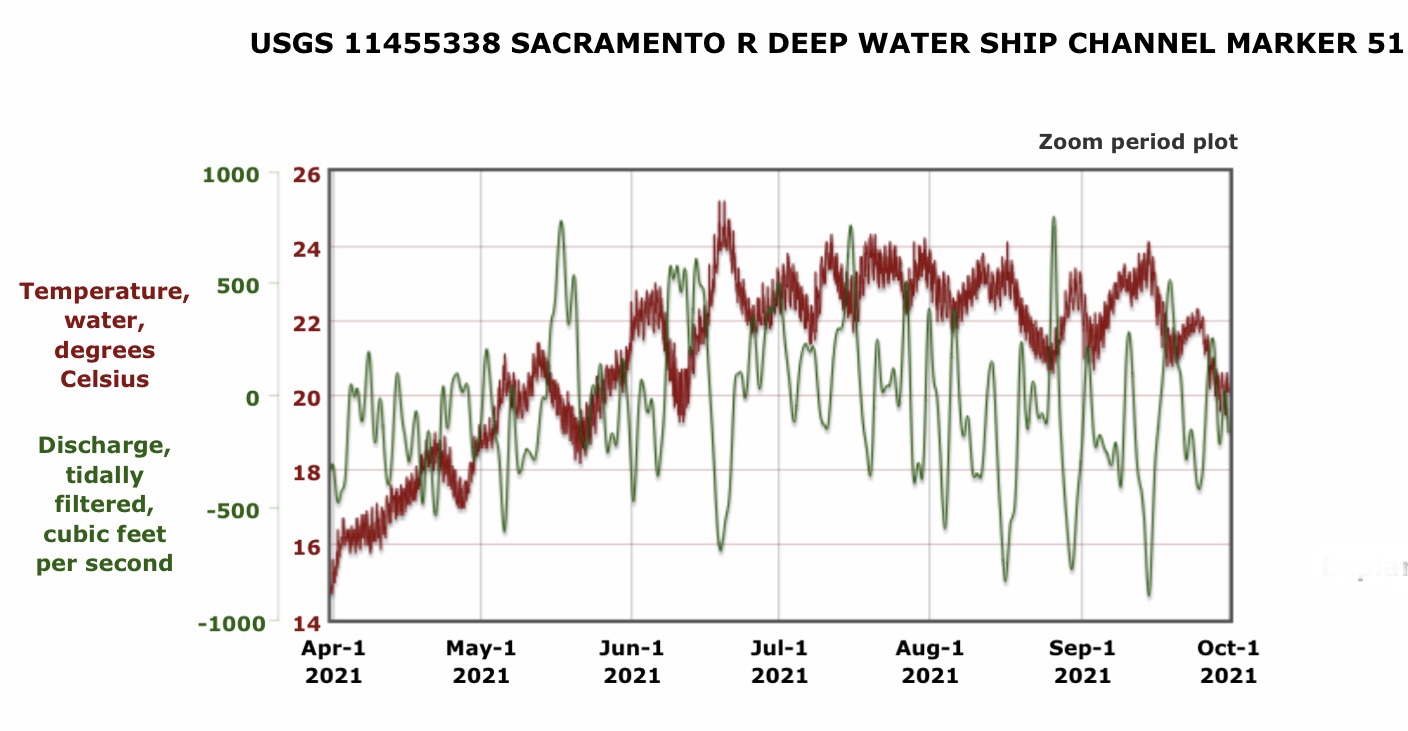

Figure 2. Turbidity and streamflow in the Klamath River near Seiad Valley below the mouth of the Scott River (rm 145) in March 2024.

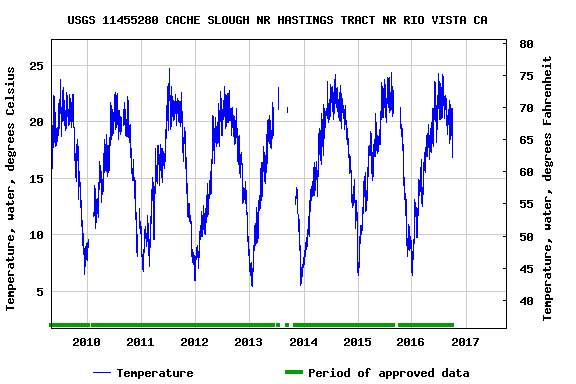

Figure 3. Turbidity and streamflow in the Klamath River near Seiad Valley about ten miles upstream from the mouth of the Scott River (rm 145) in March 2024.

Figure 4. Turbidity and streamflow in the Klamath River just upstream of Iron Gate Reservoir and below Copco dams in March 2024.