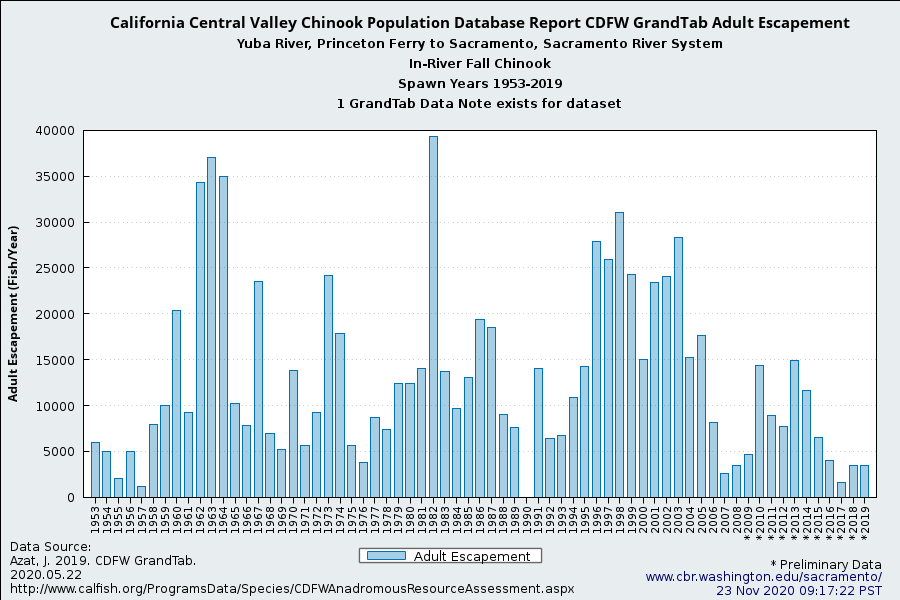

In a 2017 post and a 2018 post, I related the status of Yuba River Chinook salmon runs. The 2017 spawning escapement estimate was a record low. The 2018 and 2019 runs were not much better (Figure 1). While the record low 2017 can be blamed predominately on the 2013-2015 drought, the poor 2018 and 2019 runs cannot. Water year 2016 was a normal water year and 2017 was a wet year.

The likely culprit in the decline in Yuba escapement is the continuing persistent decline of wild spawners and increase in hatchery strays (greater than 90% of the run), leading to the erosion of the locally adapted Yuba River salmon population. This was the diagnosis for the overall Feather River population by Willmes et al., 2018.

Figure 1. Yuba River fall run salmon escapement 1953-2019.

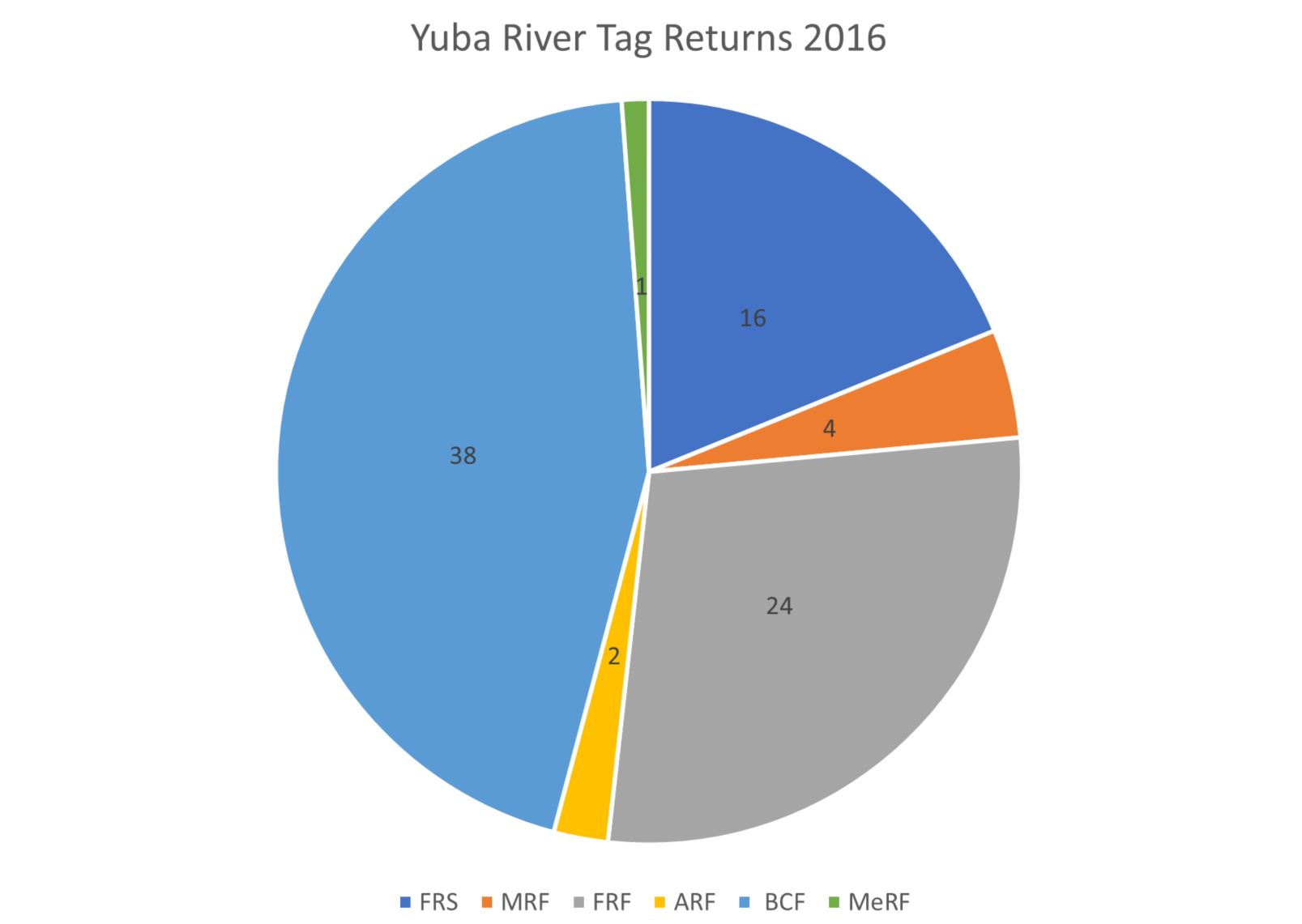

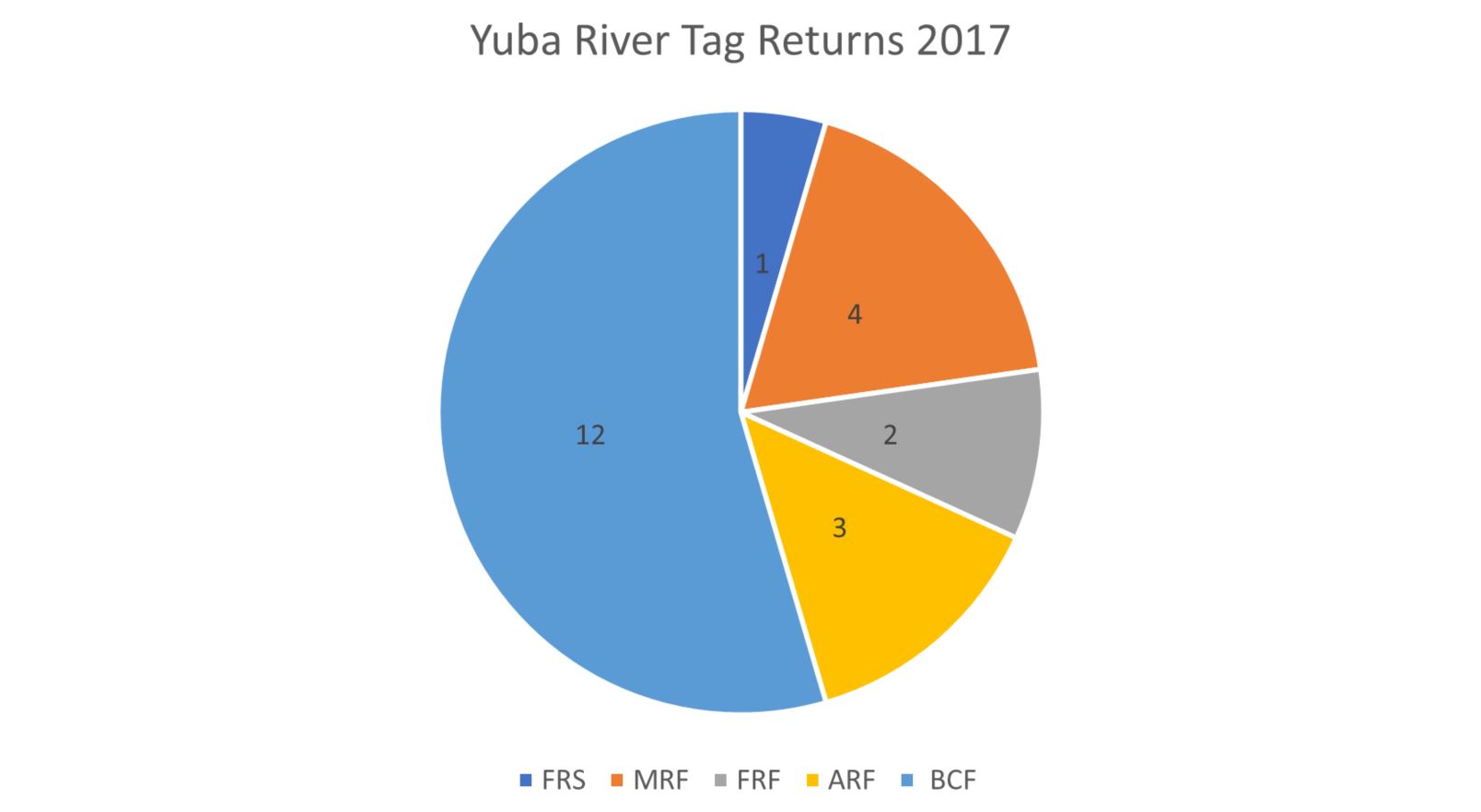

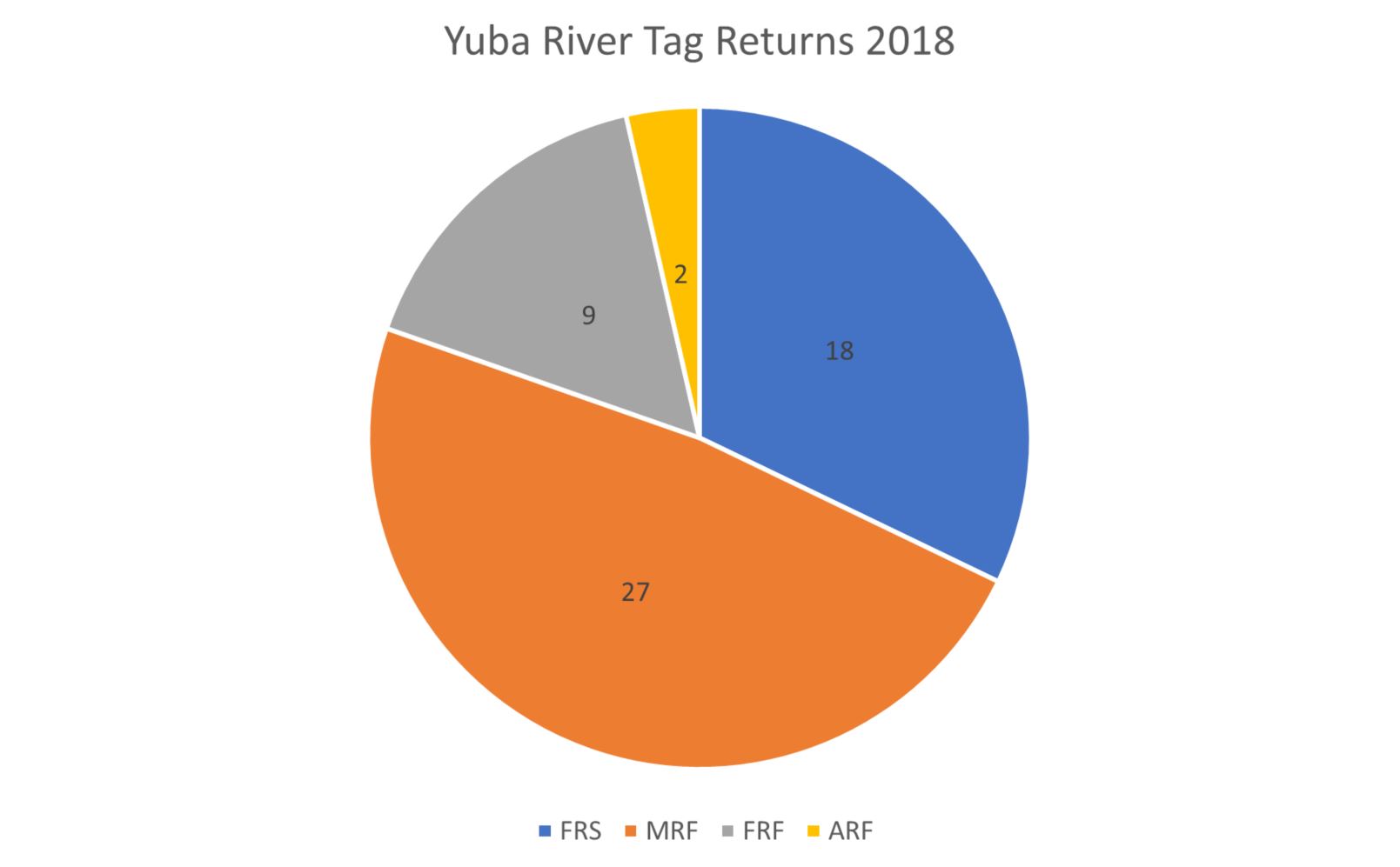

A further look at the composition of the hatchery strays in the Yuba escapement surveys provides added clues about the cause of the recent decline in overall escapement to the Yuba River. In 2016 (Figure 2), nearly half the tag returns were strays from the Battle Creek hatchery, while the other half were a combination of spring-run and fall-run strays from the Feather River hatchery, along with a smattering of strays from the hatcheries on the American and Mokelumne rivers. In 2017 (Figure 3), Yuba tag returns featured an even greater proportion of strays from Battle Creek, the American, and the Mokelumne. In 2018 (Figure 4), about half of the tag returns were from the Mokelumne River hatchery, and a third were of Feather River spring-run hatchery origin.

Feather-tagged spring-run show up consistently in the Yuba escapement surveys. This is unusual, because spring-run make up only about 10% of the Feather hatchery smolt production, with fall-run being about 90%. One reason is that spring-run smolts are 100% tagged, while fall-run hatchery smolts are only 25% tagged. Another reason is that all the spring-run smolts are released near Gridley just upstream from the mouth of the Yuba, whereas most of the fall-run smolts are released in the Bay. A third reason is that in most years springtime flows in the Yuba are higher and colder than those in the Feather, and are thus more likely to attract returning adults. Regardless of the reason, the fact that a significant portion of Yuba “fall run” escapement is derived from spring-run hatchery smolts is cause for concern.

Battle Creek hatchery fall-run made up about half the tag returns in 2016 and 2017. Much of the smolt production from the Battle Creek hatchery was trucked to the upper Bay in 2014 and 2015, a strategy prone to increased straying.1 No Battle Creek hatchery smolts were trucked to the Bay in 2016, and none showed in the Yuba in 2018. With over 10 million fall-run smolts produced at the Battle Creek hatchery (federal Coleman Hatchery near Red Bluff), nearly double the Feather hatchery production, it is easy to see why Battle Creek hatchery salmon could dominate the Yuba escapement. Without the Battle Creek, American River, and Mokelumne River hatchery strays in 2017, the record low escapement in the Yuba River would have been far worse. The fact that most of the 2017 spawners were hatchery strays from rivers other than the Feather should also be cause for concern.

In conclusion, the escapement of fall-run salmon to the Yuba River has declined over the past five years, approaching record-low levels. Spawners are now predominately hatchery strays from smolts released in the Bay and along the coast. Natural “wild” Yuba River smolt production is virtually nonexistent. This is a crying shame for what is widely regarded as one of the best non-hatchery salmon rivers in the Central Valley. I have spent many days on the Yuba River over the past two decades. I observed the big runs at the turn of the century and in 2013 and 2014. The river’s pools turned purple with adult salmon. Dead and dying salmon filled the backwaters, feeding eagles and buzzards. The odor was prevalent. Spawning salmon and redds were everywhere. Such occurrences are now rare. Our Yuba River needs so many fixes, a subject for another post.

Figure 2. Composition of tag returns from Yuba River spawners in 2016. FRS = Feather River spring run. MRF = Mokelumne River fall run. FRF = Feather River fall run. ARF = American River fall run. BCF = Battle Creek fall run. MeRF = Merced River fall run. Data source: rmis.org.

Figure 3. Composition of tag returns from Yuba River spawners in 2017. FRS = Feather River spring run. MRF = Mokelumne River fall run. FRF = Feather River fall run. ARF = American River fall run. BCF = Battle Creek fall run. Data source: rmis.org.

Figure 4. Composition of tag returns from Yuba River spawners in 2018. FRS = Feather River spring run. MRF = Mokelumne River fall run. FRF = Feather River fall run. ARF = American River fall run. Data source: rmis.org.