In the coming months and years, regulatory processes involving water rights, water quality, and endangered species will determine the future of Central Valley fishes.

To protect and enhance these fish populations, these processes will need to address four fundamental needs:

- River Flows

- River Water Temperatures

- Delta Outflow, Salinity, and Water Temperature

- Valley Flood Bypasses

In this post, I summarize a portion of the issues relating to River Flows: Fall Rains. Part 1b will cover winter river flows.

River Flows – Fall Rains

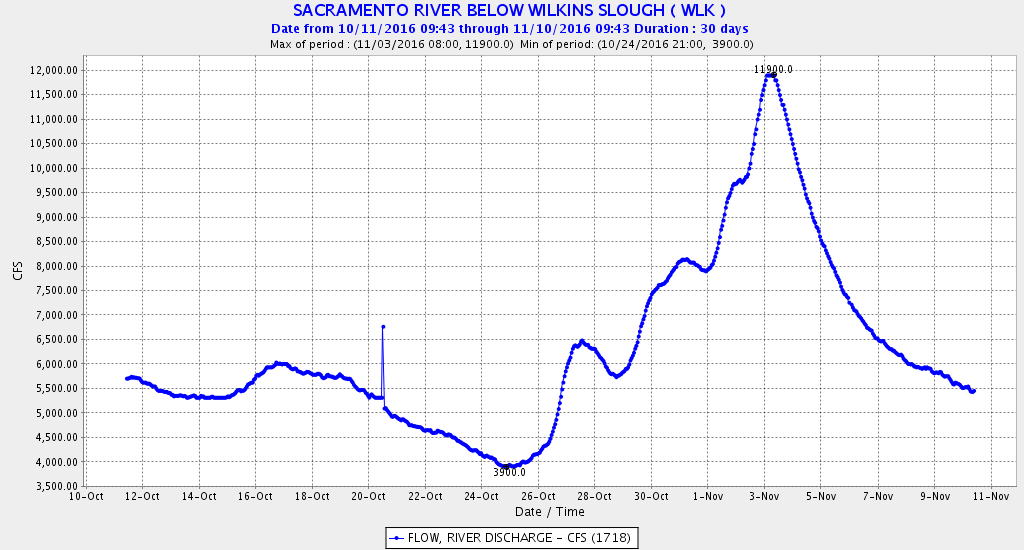

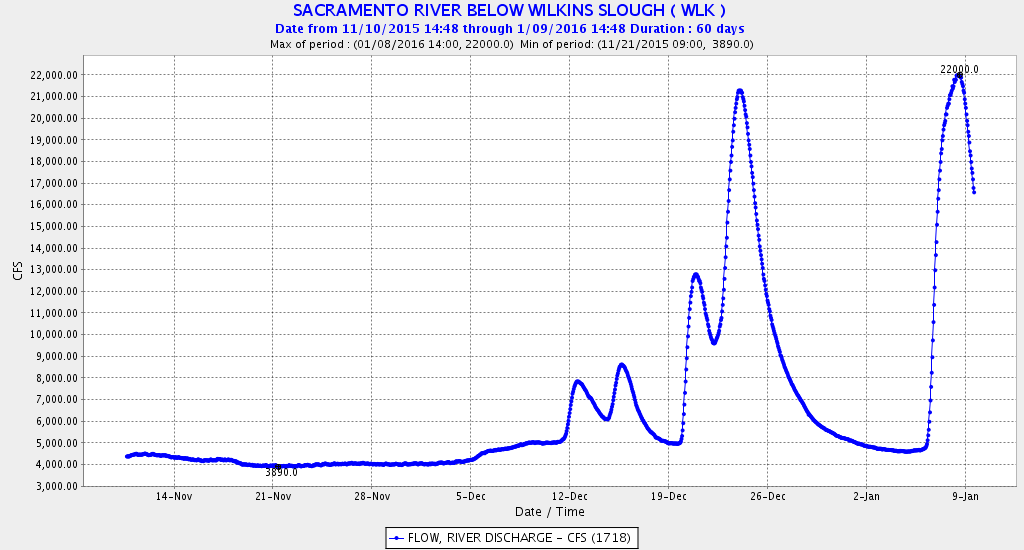

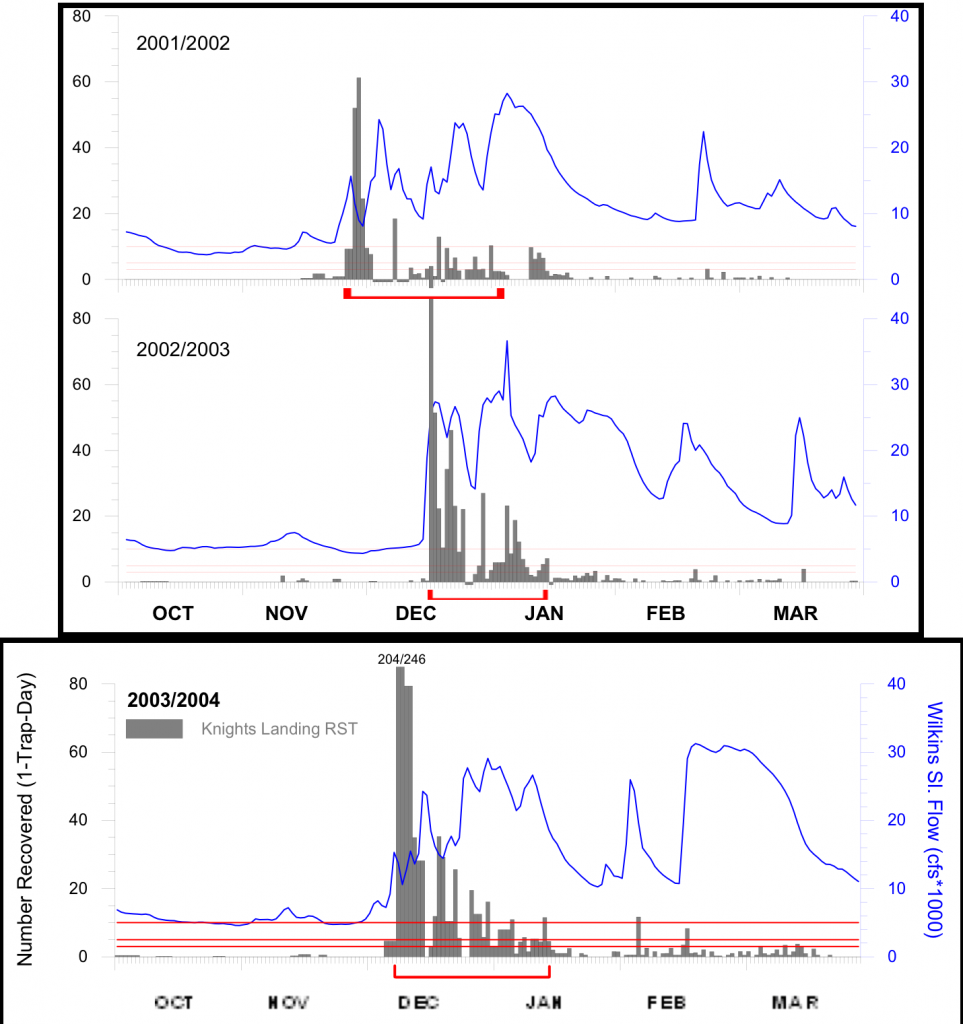

In most years, the first substantial fall rainfall stimulates many important ecological processes such as salmon and smelt spawning runs and salmon and steelhead smolt migrations to the ocean. Figure 1 below shows the effects of 2016’s late October rains, and Figure 2 below shows the effects of 2015’s December rains, in the lower Sacramento River flows at Wilkins Slough near Yuba City below Colusa. Most of these flow pulses came from storm runoff from un-dammed upper Sacramento Valley tributaries such as Cow, Cottonwood, and Battle Creeks. Such flow pulses stimulate the migrations of young salmon toward the ocean. Figure 3 below documents these migrations in the form of rotary screw trap collections at Knights Landing in the lower Sacramento River.

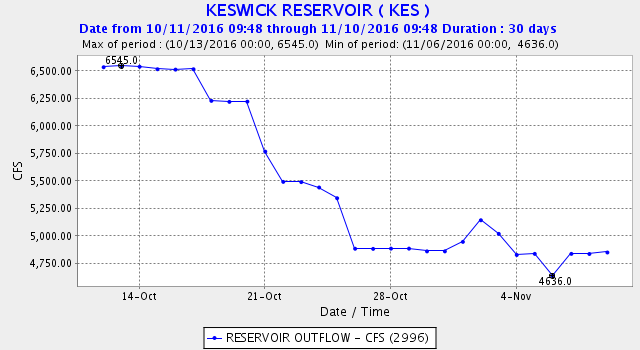

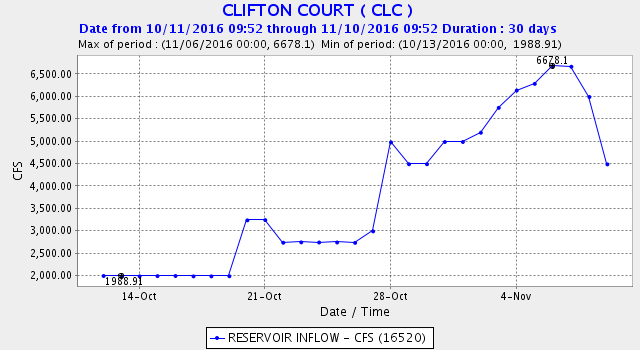

Under current operations, flows from the major reservoirs are generally held to the minimum requirement in the fall season in order to increase reservoir storage (Figure 4).1 What is needed are flow pulses (spills) from the major Valley reservoirs to the major rivers below dams, to stimulate the migration of the juvenile salmon spawned immediately downstream of these dams. Just downstream of Whiskeytown Reservoir on Clear Creek, Shasta and Keswick reservoirs on the upper Sacramento River, Oroville Reservoir on the Feather River, and Folsom and Nimbus reservoirs on the American River are vitally important salmon-producing reaches whose flow is completely controlled by the operation of the dams. Water releases timed to the natural flow pulses would stimulate migration from these important salmon-producing reaches, providing even more flow and stimulus for young salmon from all the Valley rivers to pass successfully through the Delta and Bay to the ocean.

Meanwhile, downstream in the Delta, the CVP and SWP export facilities generally ramp up exports during the initial storm pulse (Figure 5 below shows an example from 2016). Because of the importance of the initial storm pulse, the CVP and SWP should limit exports during the initial pulse, not only to help salmon get through the Delta and Bay, but also to minimize the diversion of young salmon to the south Delta.

Figure 1. Lower Sacramento River flow at Wilkins Slough in fall 2016.

Figure 2. Lower Sacramento River flow at Wilkins Slough in late fall 2015.

Figure 3. Catch of juvenile salmon in Knights Landing rotary screw traps 2001-2004 vs. flow in lower Sacramento River at Wilkins Slough.

Figure 4. Release of water from Shasta/Keswick to upper Sacramento River near Redding, fall 2016.

Figure 5. Export of water from south Delta by State Water Project, fall 2016.

- For additional discussion of the negative effects of this practice, see previous post. ↩