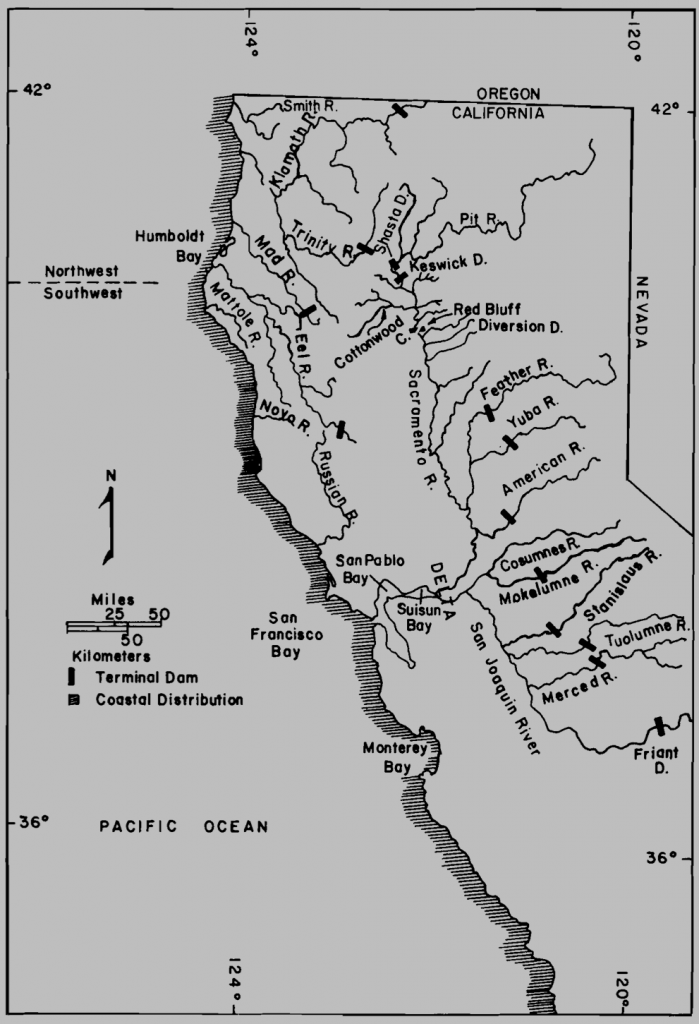

The American River is one of the larger tributaries of the Sacramento River (Figure 1). Its watershed runs from the central Sierra Nevada range, from which it runs through the city of Sacramento to join the Sacramento River. The American River’s lower 20 miles are a tailwater of the Central Valley Project’s Folsom Dam. This tailwater supports a major run of fall-run Chinook salmon that produces 15-20% of the total Central Valley fall-run Chinook salmon population.

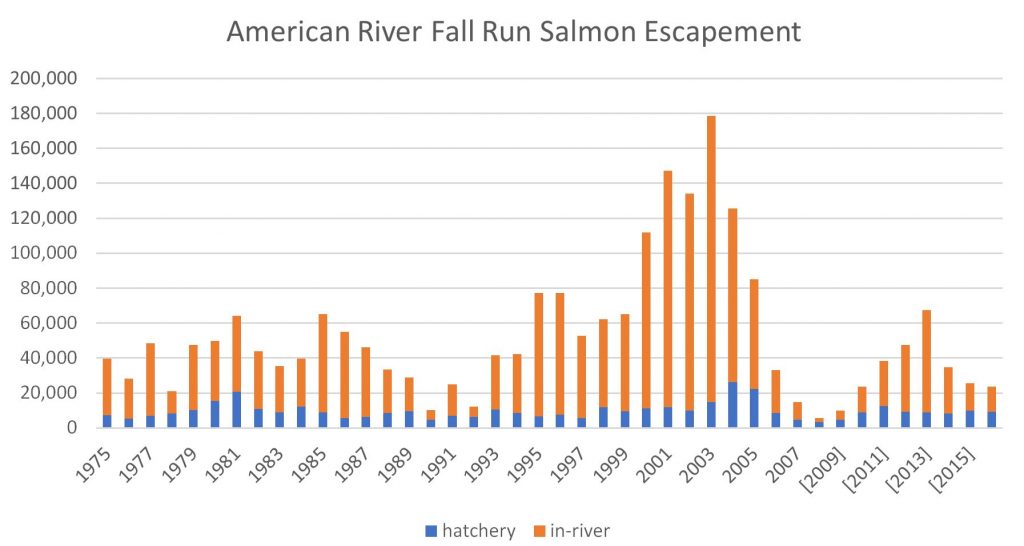

American river run size (adult escapement) has ranged from 6,000 in 2008 to 178,000 in 2003 (Figure 2). The CVPIA long-term average goal for the American River fall-run is a contribution of 160,000 adult fish to the overall goal of 750,000 for the Central Valley. Many of the American River spawners are from the American’s Nimbus hatchery, or are strays from other Valley hatcheries. However, a large part of the run spawns naturally in the upper ten miles of the lower American River below Nimbus dam within Sacramento County’s urban parkway. The hatched fry of natural spawners rear by the millions in the lower river and in the Delta. Each spring, about 5 million Nimbus hatchery smolts are trucked to the Delta or Bay and released.

The American River fall run is often considered a hatchery run, with the 20 miles of river described as a mere conduit to the hatchery. The hatchery smolts are nearly always trucked to the Bay or lower Delta because of the high potential risk from water diversions or predation in the river or the upper Delta. Trucked and Bay pen-acclimated hatchery smolts generally have a relatively high survival-contribution rate and low straying rate compared to other Central Valley hatchery tagged fish.1

Brown 2006 reviewed the status of the American River population during its peak 2000-2005 runs. He attributed the strong runs to a variety of improvements at the hatchery:

- Changes in fish ladder operations to bring fish into the hatchery later in the fall to minimize temperature problems.

- Change in egg incubation and size at release (to all smolts).

- Elimination or control of early disease problems with the help of DFG pathologists.

- Elimination of most bird depredation within the hatchery through deployment of exclusion nets over the raceways.

- Change in the DFG approach to hatchery operations since 1999 when the National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries) urged DFG to adopt standard operating procedures.

- Change in release location to San Pablo Bay and change in the method of release to net pens in place of direct releases from the transport trucks to the Bay.

Others offered additional reasons for the improvement in the fall Chinook runs in the Central Valley, including the following:

- Gravel and rearing enhancement (enhancements to spawning and rearing habitat had occurred under the CVPIA Program).

- Better hatchery practices (mentioned above)

- Good ocean conditions

- Reduced ocean fisheries

- Better instream conditions (1995-2000 were wet years)

- Some combination of the above

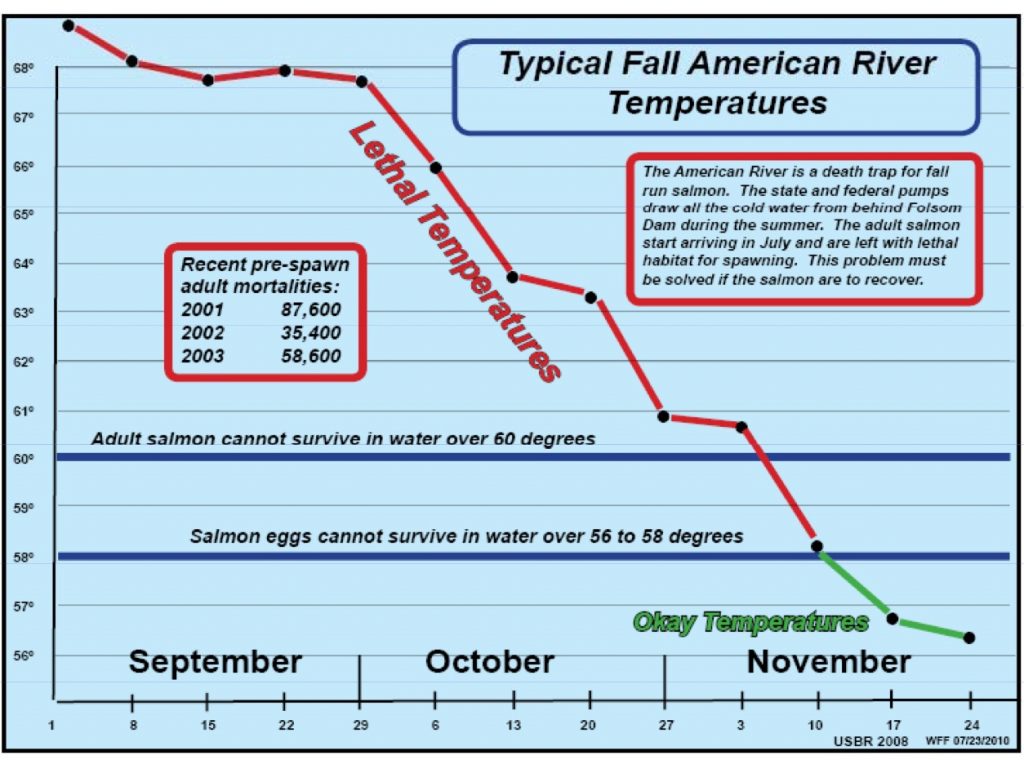

Subsequent to the good runs from 2000-2005, runs declined sharply to record lows during the 2007-2009 drought (see Figure 2). The general decline across the Central Valley was attributed mostly to poor ocean conditions.2 This seems reasonable since 2006 was a wet year with good river-Delta rearing conditions that should have produced a strong 2008 run rather than a record low run. The decline is also related to high late summer and early fall water temperatures in the lower American River that led to poor adult and egg survival (Figure 3). Such conditions occurred in the drier period of 2001-2005. I describe this specific problem in detail in a prior post.

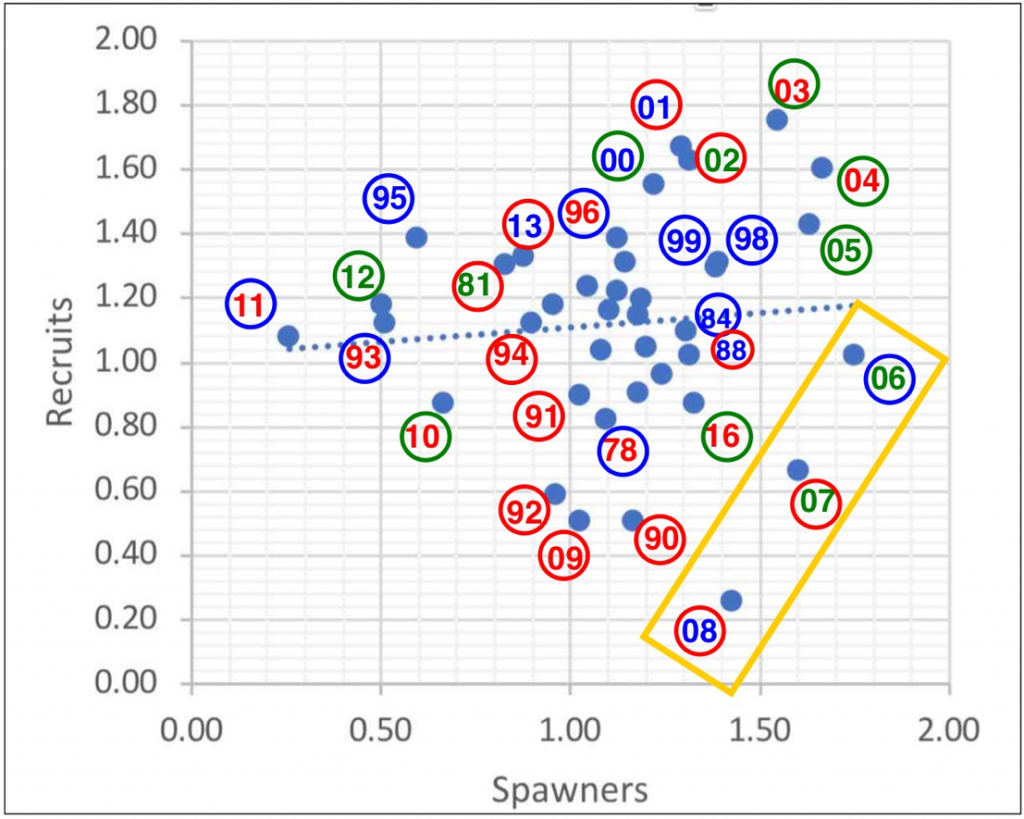

I took a closer look at the spawner-recruit relationship of the American fall-run salmon (Figure 4). There was a significant underlying positive relationship between spawners and recruits three years later. That relationship was modified by water year conditions during the rearing year (most likely the winter-spring rearing conditions) and by the fall spawning conditions in both the spawning year (from poor egg-embryo viability) and the return year (pre-spawn mortality of adults). Poor recruits-per-spawners stand out in the two drought periods 1990-1992 and 2007-2009. Years 90, 92, and 09 especially stand out with (1) poor initial spawning conditions in the fall of 87, 89, and 06, (2) poor rearing conditions in drought years (red numbers), and (3) poor spawning conditions in drought years (red circles).

Year 2008 recruits stand out in Figure 4 as the lowest recruit year despite a wet rearing year in 2006. There are at least several possible contributing factors for this particular outlier:

- Winter 2006 (Dec 05 and Jan 06) saw a large-scale flood, second only to the 1997 winter flood in recent decades. After spawning in the American River occurred during a steady flow of 2000-2500 cfs during the fall, flow reached 35,000 cfs in late December and early January, likely washing out much of the spawn. Only winter 1997 and 2017 have had similar Dec-Jan floods since 1975. Such a flood could have washed out the eggs/embryos spawned in fall of 2005, thus contributing to the poor 2008 run.

- Egg viability during the fall 2005 spawn may have been poor because water temperature was high (at or greater than 60°F) during most of the spawning season from mid-September through mid-November.

- Poor ocean conditions may have reduced survival of smolts rearing in the ocean in summer-fall of 2006.

- During the 2008 spawning season, flows were low, near 1000 cfs, and water temperatures exceeded 65°F through mid–October, likely leading to high pre-spawn mortality and lower than expected escapement. Poor conditions in the river may have attracted fewer spawners to the American or delayed their migration, leading to greater pre-spawn mortality or increased straying to other spawning rivers.

Floods during the wet winters of 1982 and 1986 may have contributed to the lower than expected runs in 1984 and 1988, respectively. Though not as strong as the Dec-Jan floods of 1997 and 2006 water years, winter floods in 82 and 86 were still substantial.

The hatchery practice of trucking smolts to acclimation pens in the Bay likely contributed to the strong runs in years 2000-2004. Lack of pen acclimation from 2003 to 2005 likely contributed to reduced runs from 2005 to 2007.

In summary, recruitment to the fall-run salmon population in the American River is a complex process affected by multiple factors. However, there are several actions that serve to keep recruitment-escapement and the contribution of the American River to California fisheries high.

- Trucking hatchery smolts to acclimation pens to San Pablo Bay contributes substantially to good salmon recruitment from the American River. Releases to pens in the Delta may reduce costs, but this comes at the expense of substantially less recruitment. Releases to the Bay allow DFW to grow fish longer in the hatchery, which contributes to higher ocean survival.

- Improvements to flow and water temperatures from September through November will reduce adult pre-spawn mortality, improve egg viability in hatchery and wild spawners, and increase wild embryo survival in redds.

- Improved late-winter and early-spring flows will improve growth and survival of juveniles rearing in the river, and improve transport of wild juveniles to Delta rearing areas.

- Though the jury may still be out on the contribution of habitat improvements to the salmon population, spawning and rearing habitat restoration in recent decades in the American River have likely helped sustain higher recruitment in good and poor water years alike. Habitat improvements increase the recruit-per-spawner capacity of salmon in the American River, especially given the relatively fixed contribution of the hatchery program. The wild or non-hatchery component of the American River salmon population also depends on Delta habitat and migratory conditions, which may also change in coming years.

Figure 1. Chinook salmon rivers. Source: Chinook salmon – species profile (USDOI 1986).

Figure 2. Fall run Chinook salmon escapement (river and hatchery counts) to the American River 1975-2016. Data Source: CDFW GrandTab.

Figure 3. “The American River is a death trap for fall run salmon” because of high water temperatures. Source: http://water4fish.org/res/pdf/salmon_status_and_needs_2011.pdf

Figure 4. Recruits (escapement in numbered year) per spawners (escapement three years earlier) for years 1978 to 2016 (log10 transformed). Red number denotes rearing conditions in a dry water year two years earlier. Red circle denotes dry water year in spawning year. Green denotes normal water year. Blue denotes wet water year. For example: Spawning year 2011 had dry rearing conditions in 2009, wet year during its spawning run in 2011, and the lowest number of parents in 2008. Orange rectangle represents years having poor ocean rearing conditions. Note that for recruit years 00-04, hatchery smolts were trucked to Bay acclimation pens (1998-2002), whereas in 03 to 05 they were trucked to Bay for direct release or to Delta pens.