Following some improvement in the numbers of adult fall-run Chinook salmon returning to spawn in the Stanislaus River and the Merced River from 2012-2017, overall escapement in 2020 and 2021 to San Joaquin River tributaries was severely depressed. Better flows and water temperatures could help reverse this decline.

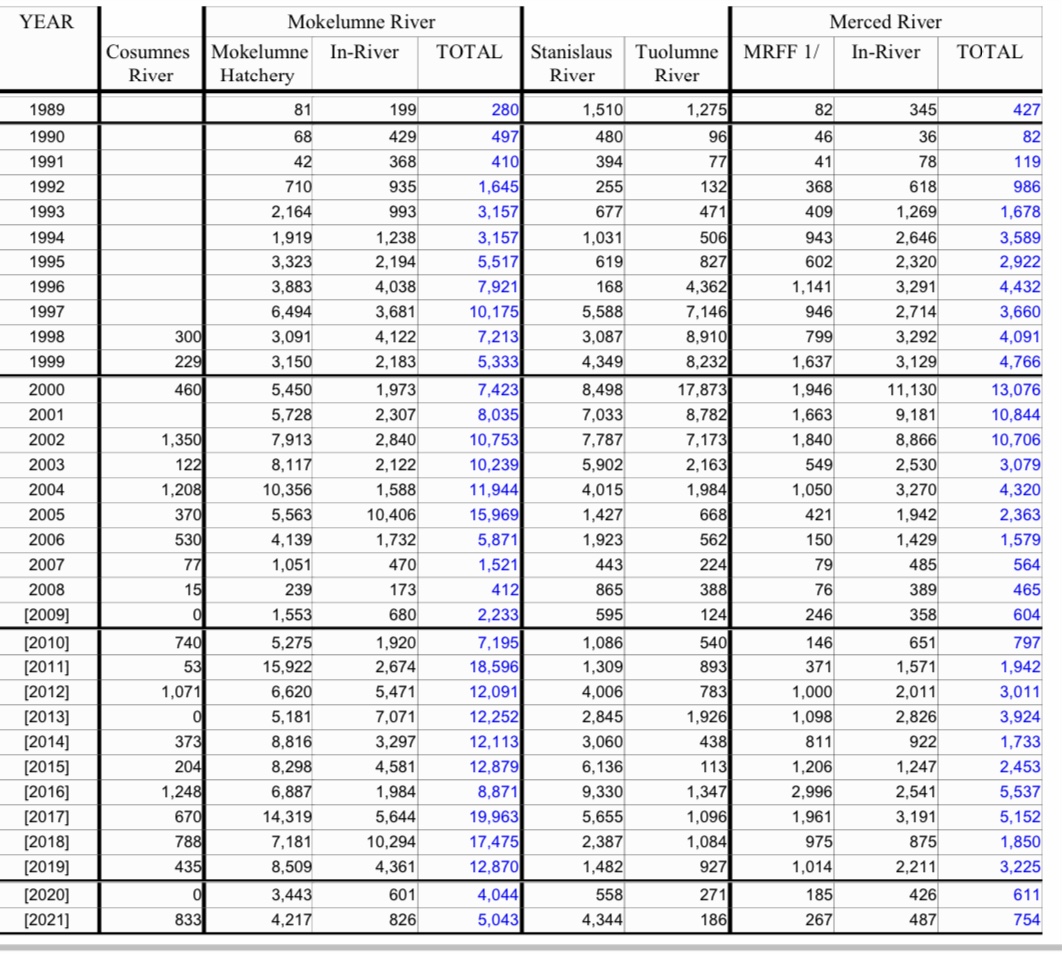

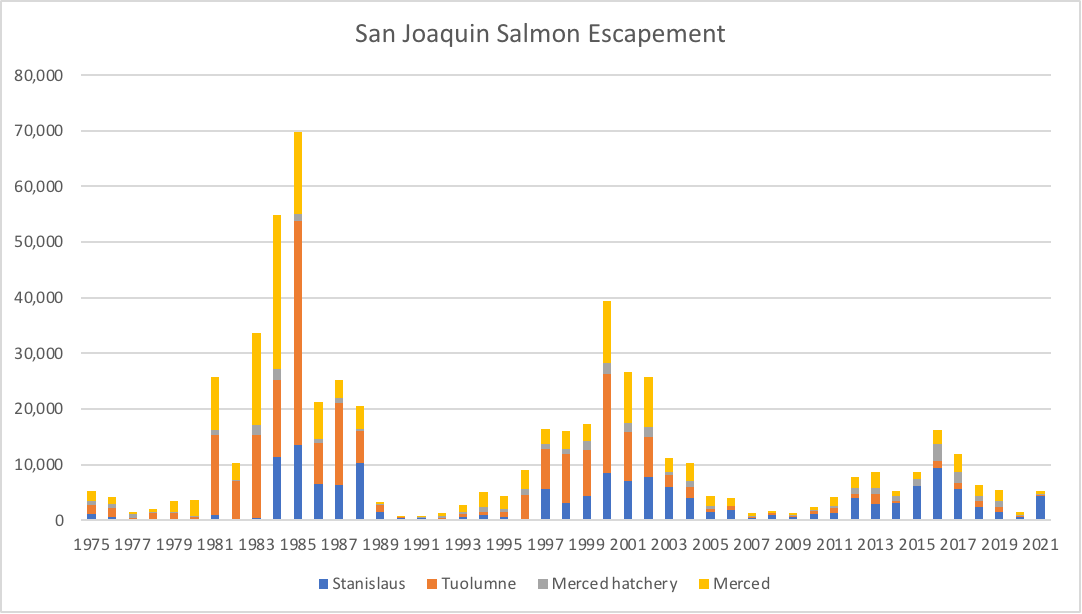

In February 2017, I wrote about the fall Chinook salmon runs on the San Joaquin River’s three major tributaries over the previous six years. Salmon counts in San Joaquin tributaries showed an increase in returning adults in the 2012-2015 drought compared to the poor returns in 2007-2009 drought (see Figures 1 and 2). The numbers of spawners in 2012-2015 were still well below the returns in the eighties and nineties that corresponded to wet water year sequences, but the increase seemed to suggest progress.

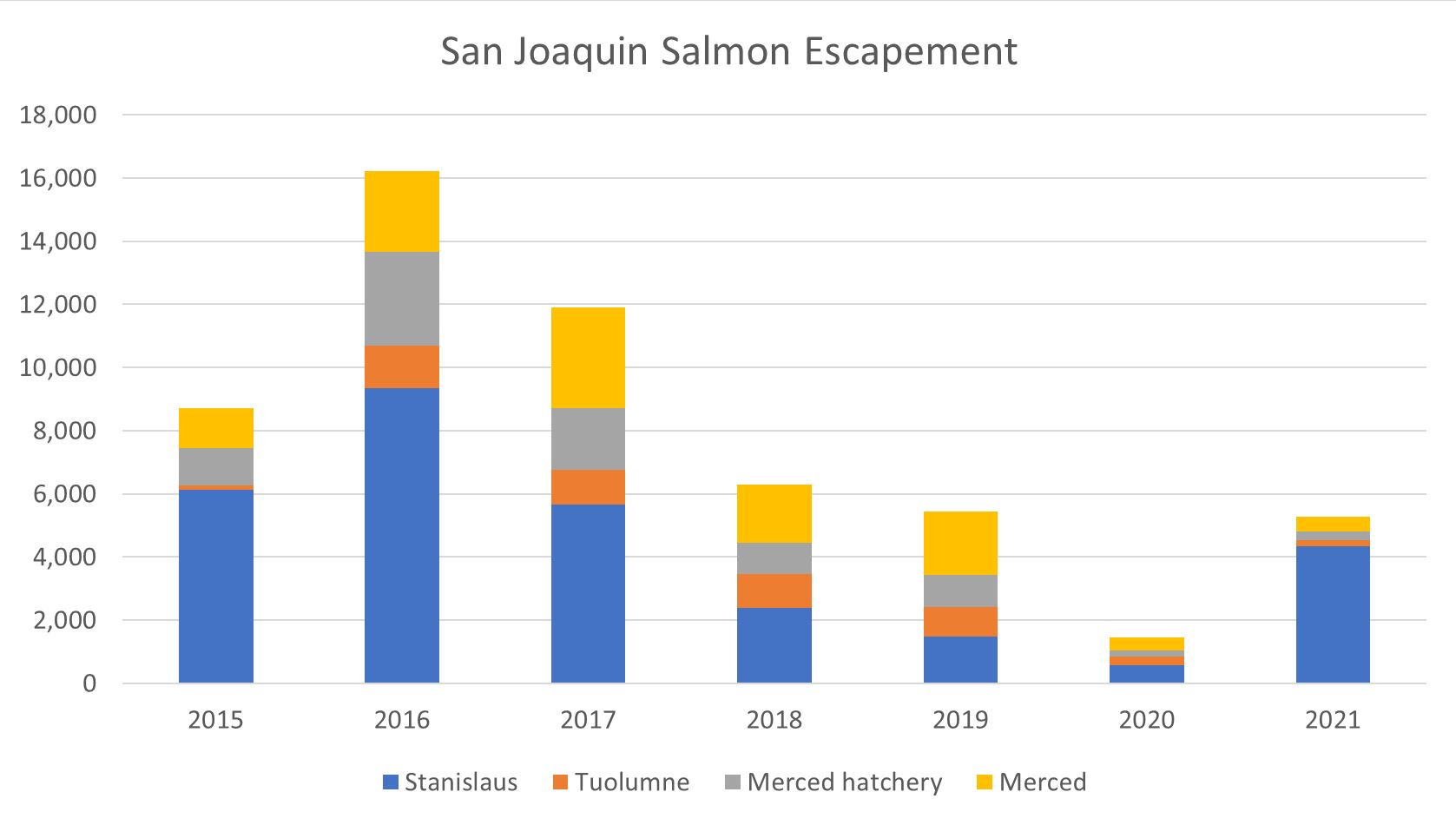

In a December 2019 update, I updated the earlier post with numbers from the 2016-2018 runs. The 2016 and 2017 runs were the product of poor rearing conditions in 2014 and 2015, both critical drought years, but with good fall adult migration conditions. The 2018 run was a product of normal-water-year rearing (2016), but poor adult migrating conditions. The 2016 and 2017 runs were strong in the Stanislaus and Merced rivers (see Figure 3), with both rivers benefitting from hatchery production and strays. The markedly smaller runs in the Tuolumne (typical throughout the last decade) also benefitted from hatchery strays (Figure 4). One strong component of the strays was the unusually high proportion of strays from the upper Sacramento River’s Battle Creek hatchery, whose managers’ strategy during the 2014-2015 drought was to truck their fall-run salmon smolts to the Bay, a practice that causes high straying rates, including to the San Joaquin tributary runs.

The 2018 San Joaquin run was lower, but still an improvement over the drought-influenced runs in 2007-2011 (Figure 2). Spring rearing conditions in 2016 and fall adult migration conditions in 2018 were generally better than they were during the critical drought years, although still stressful. Also, most of the Mokelumne and Merced hatchery smolts were released to the Bay and west Delta, respectively, in 2016, a likely positive factor in contributing strays to overall escapement. A further explanation for this improvement was better hydrology-related habitat and migration conditions prescribed in the 2008-09 federal biological opinions that generally led to improved habitat conditions.

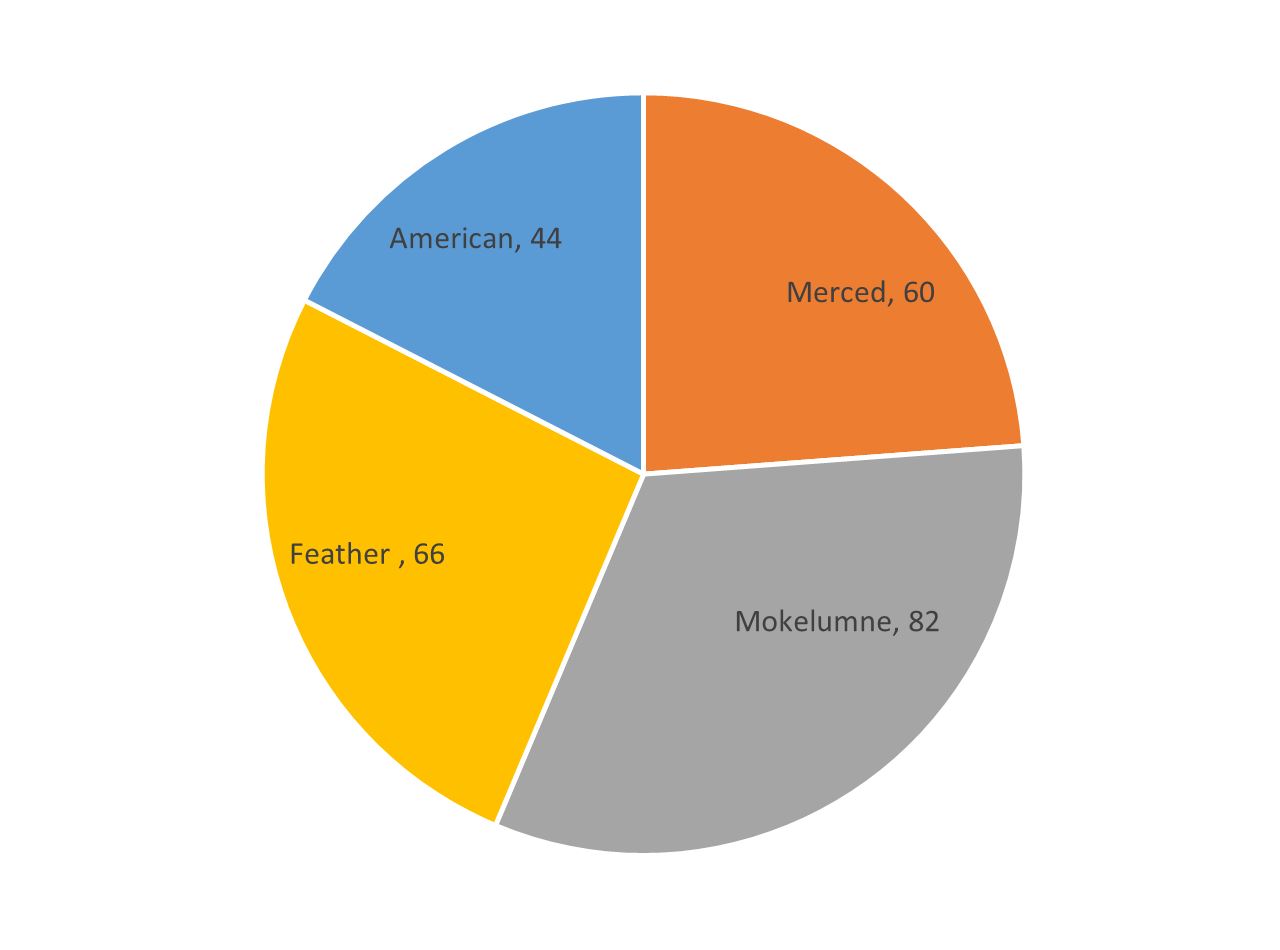

In the three years (2019-2021) since 2018, runs generally declined (Figure 3) despite being the product of two wet (2017 and 2019) and one normal (2018) year. One reason for the reductions was that there were fewer strays from hatcheries. For example, the Merced hatchery smolt releases in 2017 were at the hatchery instead of in the Bay, and thus had poor returns. Battle Creek hatchery returns were also lower, with less straying by smolts released near the hatchery.

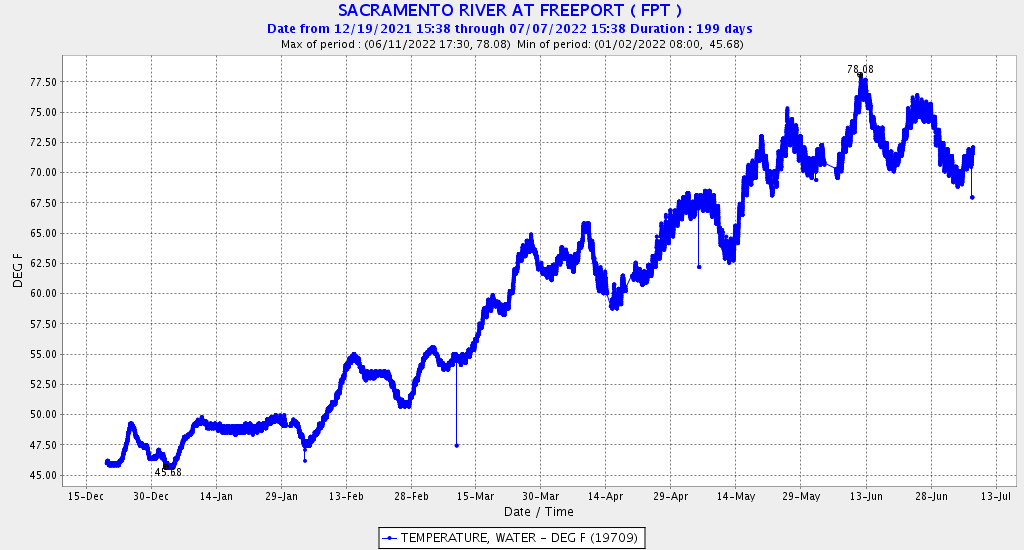

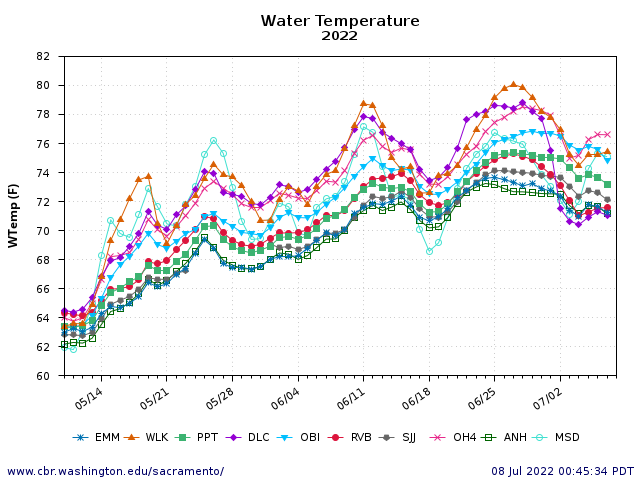

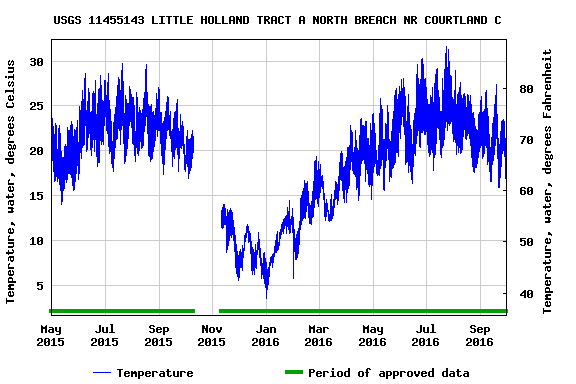

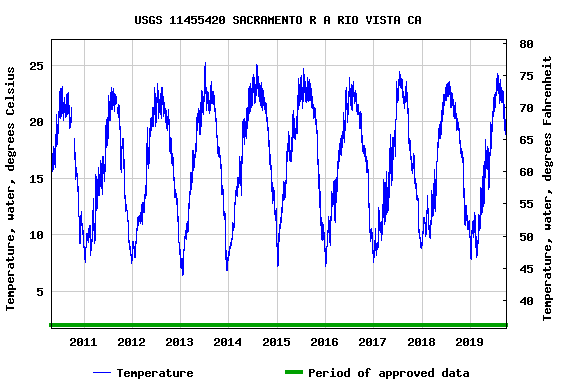

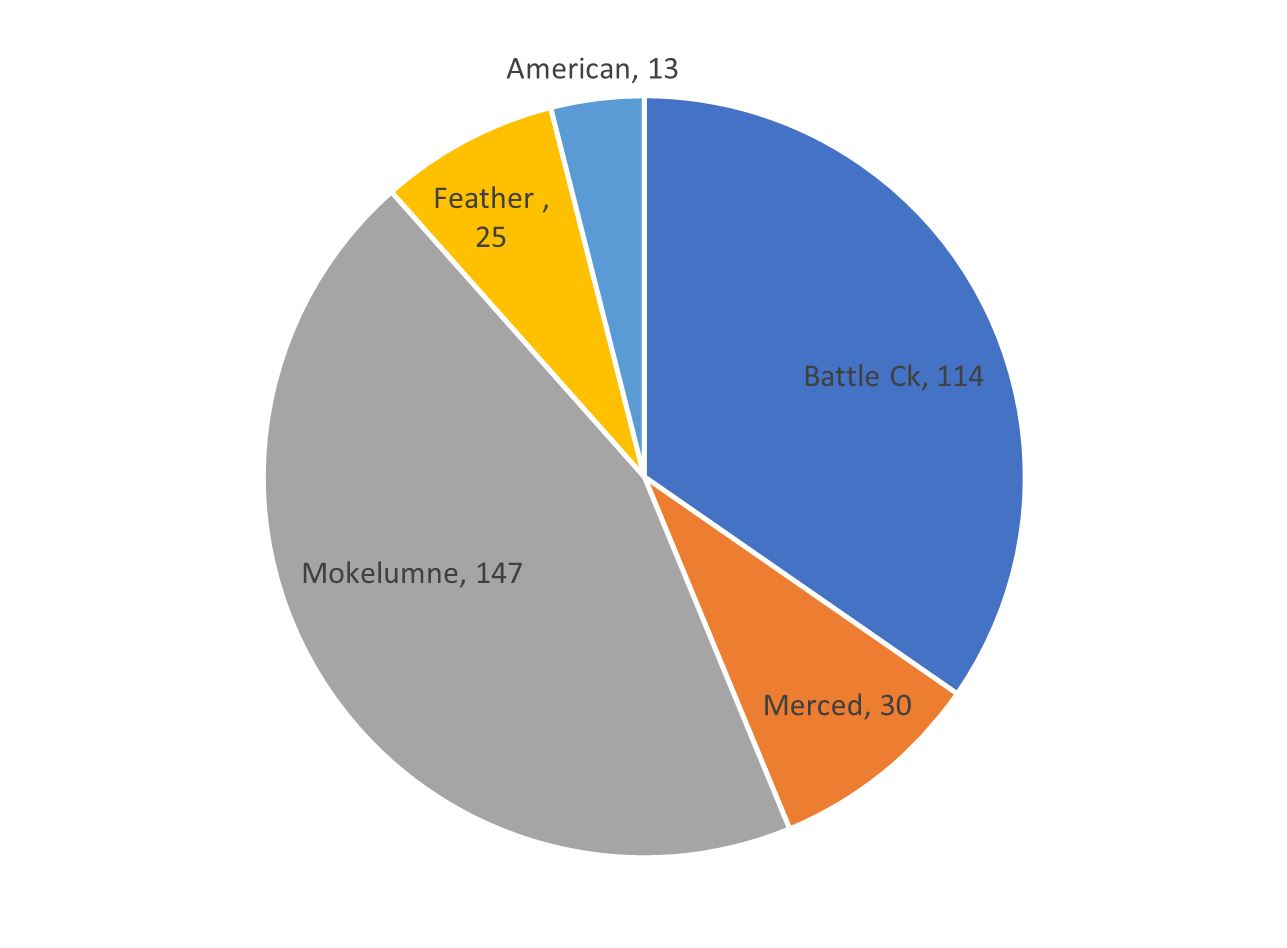

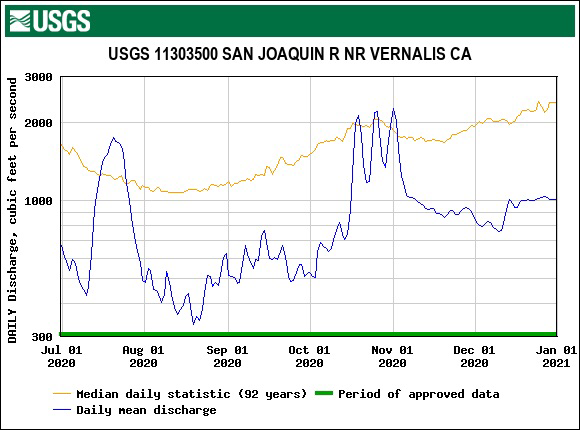

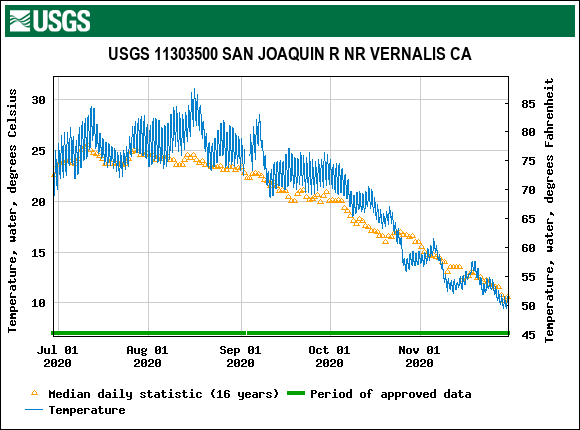

The poor returns in 2020 in all three rivers are especially troubling, given they are the product of a good wet year run (2017) and reasonable rearing conditions in winter and spring of normal year 2018. One factor in the San Joaquin watershed in late summer and early fall 2020 was unusually low flows and high water temperatures for a normal water year (Figures 5 and 6). Based on the high number of returns of 2018 Merced hatchery smolt releases straying to other rivers (Figure 7), it appears that a compounding factor to these low flows and high water temperatures was high rates of straying by salmon sourced in San Joaquin watershed to the Mokelumne, American, and Feather Rivers.

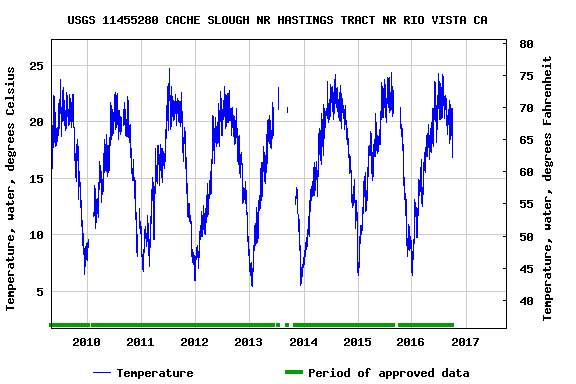

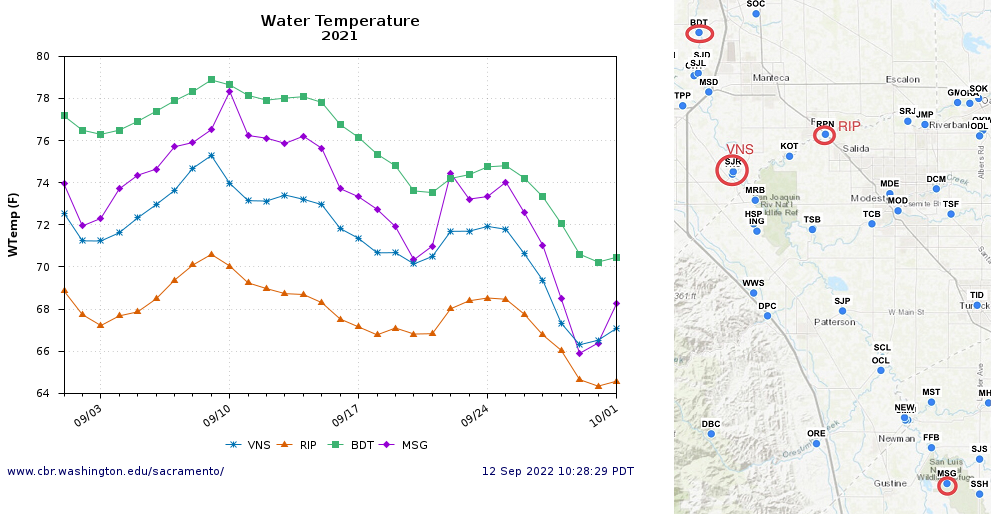

The relatively high proportion of the Stanislaus River escapement in the 2021 San Joaquin run appears to be a result of attraction to the Stanislaus from a very warm lower San Joaquin River (Figure 8). The Stanislaus is the first cool tributary encountered by salmon on their journey up the warm San Joaquin in late summer and early fall.

In summary, there is much straying to and from the San Joaquin salmon spawning tributaries. Adult run size (escapement) is a function of straying, winter-spring flows and water temperature in the San Joaquin and its tributaries during the winter-spring rearing season, and streamflows and water temperatures during the annual late summer and fall spawning run. The release locations of smolts from the Merced River hatchery and other hatcheries also plays a role.

Salmon runs to the San Joaquin and its tributaries could be improved with better streamflow and water temperature management.

Figure 1. Fall run salmon escapement to San Joaquin River and tributaries 1989-2021. Source: Grandtab.

Figure 2. Plot of 1975-2021 fall run salmon escapement to San Joaquin River tributaries. Data source: GrandTab.

Figure 3. Plot of 2015-2021 fall run salmon escapement to the San Joaquin River tributaries. Data source: GrandTab.

Figure 4. Returns of code-wire-tagged (cwt) salmon to Tuolumne River in 2016-2017 from five Central Valley hatcheries. Source: cwt return data in https://www.rmpc.org.

Figure 5. July-December water temperature in San Joaquin River at Vernalis in 2020, and historical average.

Figure 6. July-December streamflow in San Joaquin River at Vernalis in 2020, and historical average.

Figure 7. Adult spawner returns to four hatcheries and spawning grounds in 2020 of 2018 Merced Hatchery tagged smolts released in Bay. (Note there were no records for Battle Creek returns.)

Source: cwt return data in https://www.rmpc.org.

Figure 8. Water temperatures in the lower San Joaquin River at Vernalis (VNS), Brant Bridge (BDT), and Mud Slough (MSG), and Ripon (RIP) on the lower Stanislaus River in September 2020. Note adult salmon generally avoid 72°F water.