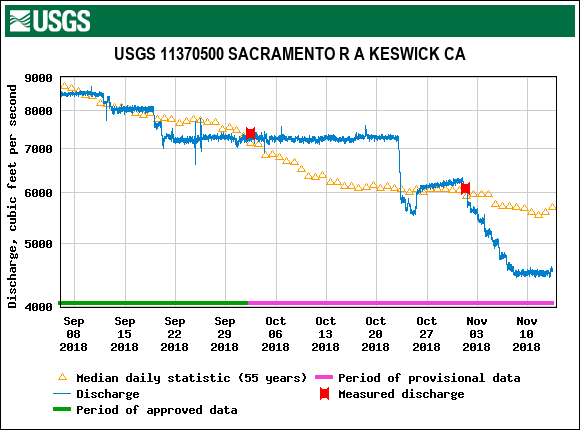

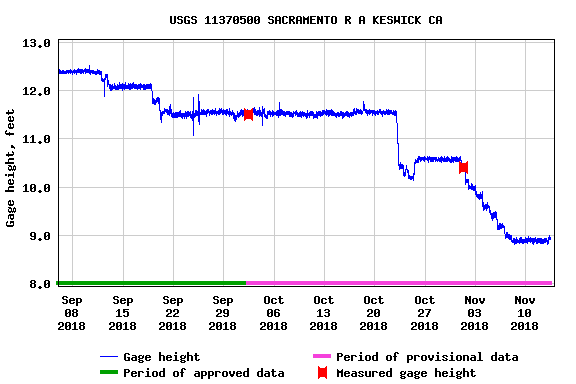

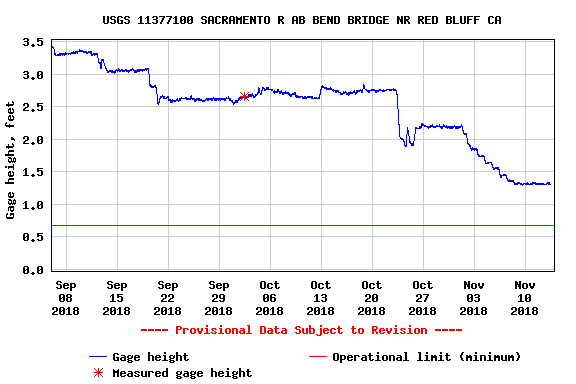

In a past May 2018 post I described how fall-run salmon redd dewatering was a key factor in the poor wild salmon production in the Sacramento River during the two prominent salmon population crashes in the past decade. This problem is again occurring in fall 2018 (Figures 1-3). The close to 50% drop in flow releases from Shasta Dam since late October and the corresponding 2-to-3 foot drop in water level is causing redd stranding of spring-run and fall-run salmon in the spawning grounds of the Sacramento River below Shasta.1

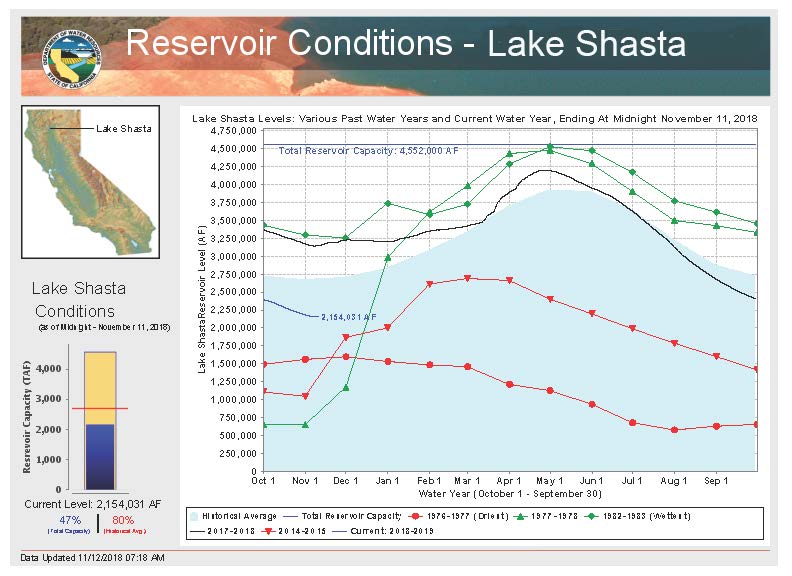

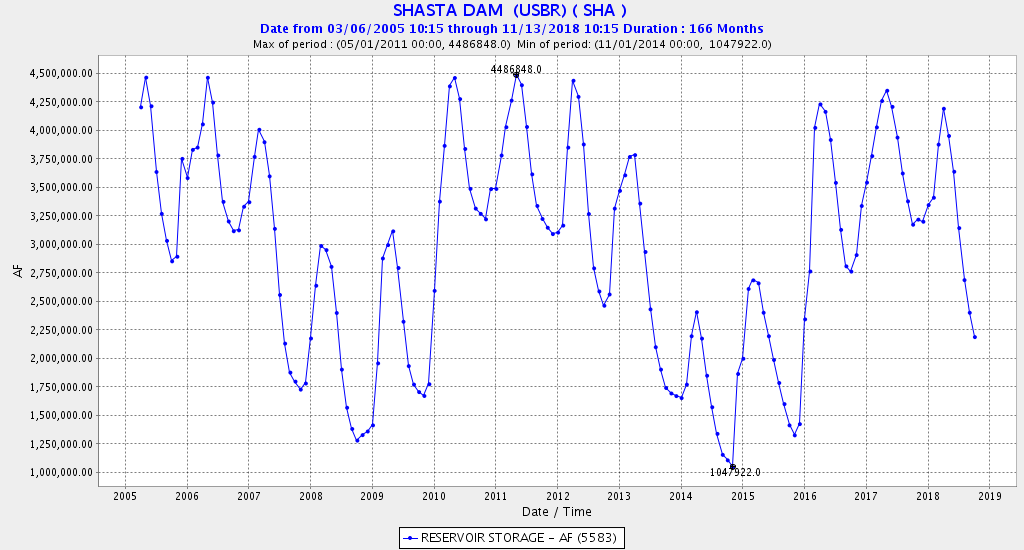

Despite nearly filling this past spring, Shasta Reservoir was drawn down over the summer and fall (Figures 4 and 5). The decline is unprecedented and is more typical of critical drought years. I recognize the concern for Shasta storage, but Reclamation’s decision to provide 100% water allocations under low snowpack conditions has again compromised Sacramento River salmon production.

Figure 1. River flow (cfs) below Shasta/Keswick in the Sacramento River in fall 2018 along with long term average.

Figure 2. Water surface elevation in Sacramento River below Keswick Dam at upper end of prime salmon spawning reach in fall 2018.

Figure 3. Water surface elevation in Sacramento River near Red Bluff at lower end of prime salmon spawning reach in fall 2018.

Figure 4. Shasta Reservoir information in 2018.

Figure 5. Monthly Shasta reservoir storage 2005-2018.