Background

The Sacramento River below Shasta-Keswick near Redding is the spawning reach of Winter-Run Chinook salmon in summer. Winter-Run originally spawned in the cold, spring-fed reaches upstream of Shasta Reservoir. Since Shasta Dam’s construction over a half century ago, Winter-Run have spawned below in Shasta’s cold tailwater. However, in some dry years the cold water has run out and the Winter-Run spawn has failed, as was the case in late summer 2014. There simply are not sufficient guarantees in the State Water Right Order 90-5 (WRO-90-5) or the NMFS Biological Opinion (BO) to protect the Winter-Run: there weren’t in 2014 and there aren’t in 2015. Winter-Run need cold water (<56°F) through the summer to protect spawning adults, eggs laid in gravel, and fry developing in gravel beds throughout their spawning reach upstream of Red Bluff. In nearly all years there is sufficient cold water in Shasta to sustain cold water through the summer above Red Bluff, especially after construction of the Shasta Dam Temperature Control Device (TCD), which allows conservation of the coldest water in Shasta through the summer. The problem is that the cold water cannot be conserved because of downstream demands on the water.

Downstream agricultural demands force the release of too much of the Shasta cold water pool in spring and summer, which in drier years like 2014 and 2015 results in exhaustion of the cold water pool by late summer. To complicate matters, warmer Trinity water is brought over for release below Shasta to meet some of the downstream demands, thus requiring even more of the Shasta cold water pool to maintain target temperatures above Red Bluff. Shasta releases also are highest in warm afternoons to meet peak power demands; this release pattern also requires more from the cold water pool.

The federal and state agencies develop a plan to operate the system each year in the winter prior to the irrigation season. Based on what they know and forecast for the upcoming season, they develop a plan to maintain cold water through the summer for the salmon, as well as a forecasted water supply for downstream users. Both the WRO-90-5 and BO contain provisions that allow the targets for salmon temperatures to be modified in dry years to allow downstream water users a portion of their normal water supply.

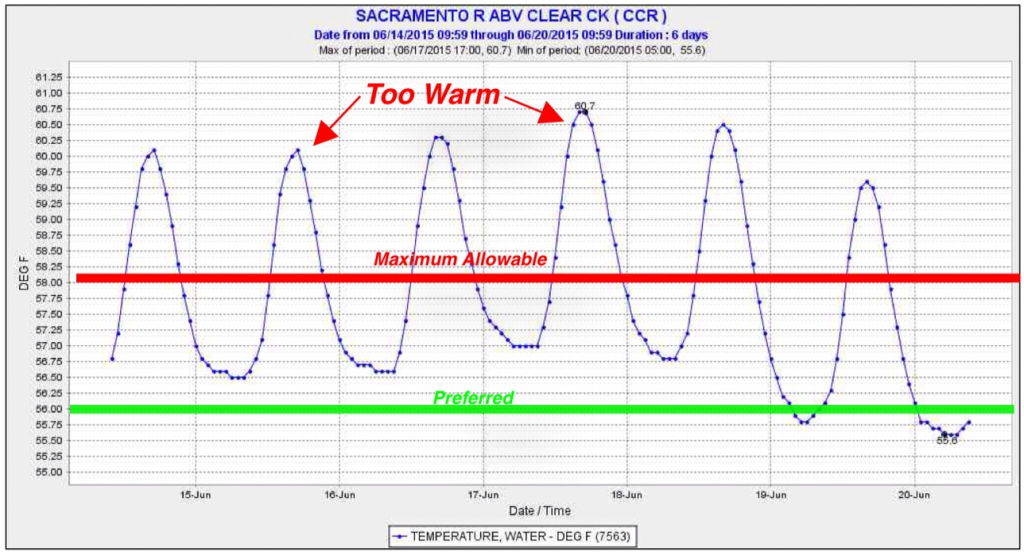

WRO-90-5 allows weakening of targets for water temperature by moving the compliance point upstream from Red Bluff, sometimes as far as Redding. In 2015 the State Board in a Temporary Urgency Change Order allowed the target temperature to be raised to a daily average of 58°F in Redding.

The Problem

Both the 2014 and 2015 plans failed to meet their objectives for a multitude of reasons, least among them inaccurate information and poor planning tools (e.g., mathematical models). Lack of conservative conditions in the plan and follow-up conservative decision-making were the key problems. In 2014, the plan and operational failure led to the loss of most of the 2014 Winter-Run salmon production; the Winter-Run perished in low flows and high water temperatures in late summer in the small spawning reach upstream of Highway 44 in Redding. By late spring of 2015, it became apparent, as predicted by CSPA and others, that the Bureau had allocated spring releases (already made to downstream users) based on a forecast that overestimated the size and quality of the Shasta cold water pool . So the State Board allowed the Bureau of Reclamation to adopt a new temperature management plan, raising the target to an average daily temperature of 58°F even in the tiny amount of the Sacramento River between Keswick Dam and Clear Creek.

What more can be done?

First, rescind the weakened numeric target because it does not protect salmon eggs and newly newly hatched fry. The 56°F target must be reinstated as far downstream as possible. The SWRCB should at the very least ensure that maximum water temperatures never exceed 58°F and that average daily and weekly average maximums do not exceed 56°F.

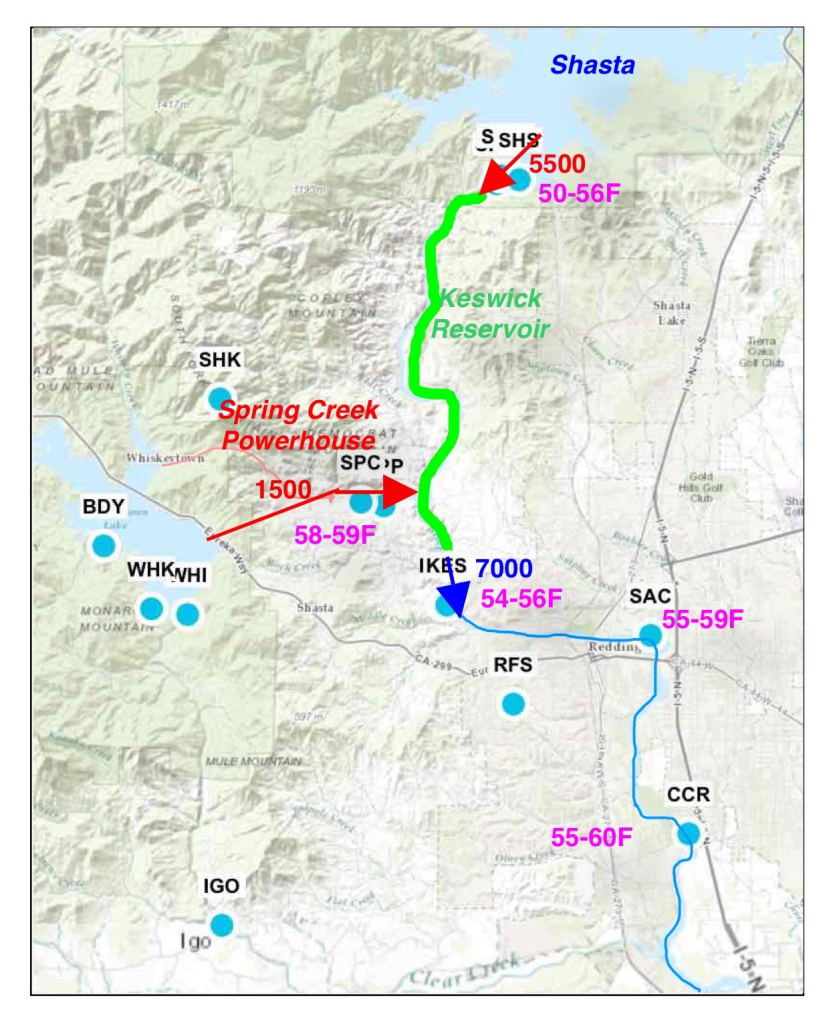

Second, reduce the input of warmer Trinity water via Whiskeytown and the Spring Creek Powerhouse. The chart of present conditions below shows that the warmer Trinity water entering Keswick Reservoir below Shasta makes up over 20% (1500/7000) of the water entering the Redding reach. Ensuring that the Redding reach target is maintained requires that more 50°F cold-water pool water from Shasta be mixed into the TCD than would be necessary to maintain the mandatory 58°F average daily target at Redding (CCR location) without the Trinity water. Cutting the Trinity input at this time would be especially prudent. Low flows in the Trinity (460 cfs release to river, compared to 1500 cfs diversion to Sacramento River) are contributing to disease and die-off of salmon in the lower Klamath-Trinity system. {Note: it may not be possible to reduce Trinity inputs without increasing Shasta releases because salmon have or are now spawning at these flows. Cutting Trinity inflow could still reduce demand on Shasta cold water pool water even if Trinity flow cuts are made up by Shasta water.}

Second, reduce the input of warmer Trinity water via Whiskeytown and the Spring Creek Powerhouse. The chart of present conditions below shows that the warmer Trinity water entering Keswick Reservoir below Shasta makes up over 20% (1500/7000) of the water entering the Redding reach. Ensuring that the Redding reach target is maintained requires that more 50°F cold-water pool water from Shasta be mixed into the TCD than would be necessary to maintain the mandatory 58°F average daily target at Redding (CCR location) without the Trinity water. Cutting the Trinity input at this time would be especially prudent. Low flows in the Trinity (460 cfs release to river, compared to 1500 cfs diversion to Sacramento River) are contributing to disease and die-off of salmon in the lower Klamath-Trinity system. {Note: it may not be possible to reduce Trinity inputs without increasing Shasta releases because salmon have or are now spawning at these flows. Cutting Trinity inflow could still reduce demand on Shasta cold water pool water even if Trinity flow cuts are made up by Shasta water.}

This map depicts conditions in the first week of August 2015. Daily average Shasta releases to Keswick Reservoir are approximately 5500 cfs. Daily average Whiskeytown releases to Keswick are 1500 cfs. Keswick release is approximately 7000 cfs. The daily range in water temperatures is shown by location in magenta. Gaging and recording stations are blue dots (from CDEC).

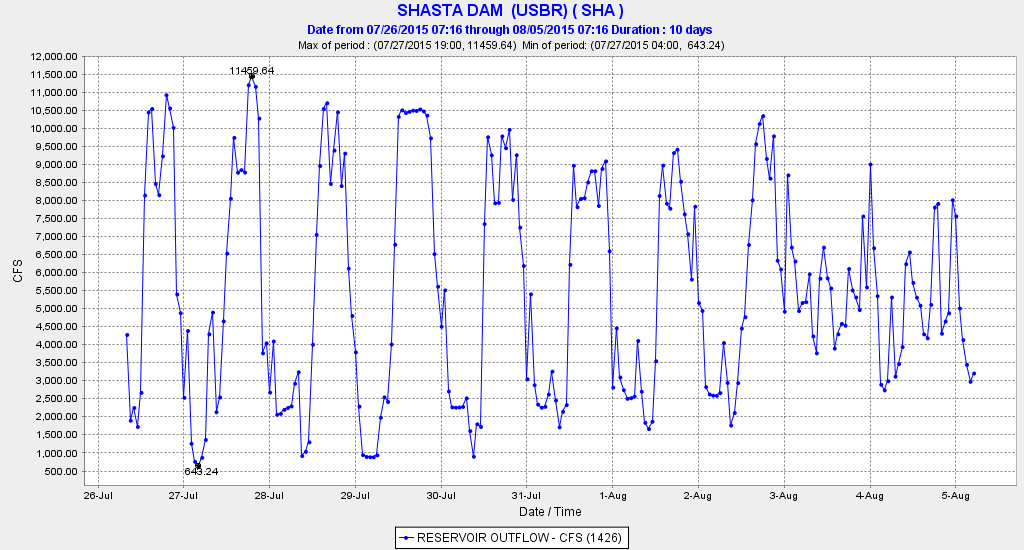

Third, reduce hourly peaking power releases from Shasta, because water released through the Shasta powerhouses is pulled from relatively high in the water column, and is thus relatively warm. Data from the past several days indicates Reclamation may already be instituting this measure – see figures below.

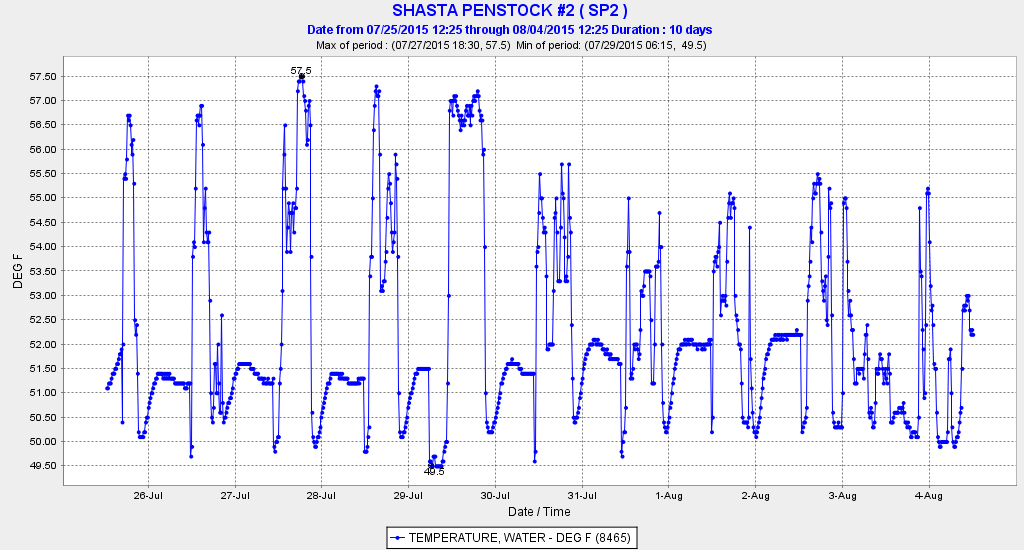

Water temperature recordings from one of five Shasta Dam penstocks over past ten days note high daytime water temperatures.. Lower maximum temperatures in last five days may be from reduced daytime releases or changes in TCD operation (see chart below).

Note high daytime releases to meet peak power demands. Note Reclamation has altered the normal pattern in the last two days, which apparently further reduced release water temperature (see chart above).

In summary, saving Winter Run Chinook salmon this summer demands immediate action. This will require one or more of the following: reduced reservoir releases to downstream users, less transfer of warm water from Trinity Reservoir (via Whiskeytown and Spring Creek Powerhouse), reduced power generation, less peaking power operation, and/or the bypass of releases past Shasta’s power generation facilities (use of Shasta Dam’s lower level outlet).

Recently, I had fresh, wild, troll-caught

Recently, I had fresh, wild, troll-caught