The big hype over the past several decades in the Central Valley has been Adaptive Management. Whatever happened to it? Did we forget about it, or simply take it for granted? Did we rebrand it, morph it into something else? I wrote a “white paper” on the topic for CALFED over 20 years ago. My version was more about conducting experiments to address unknowns to help inform management decisions.

The definitions immediately below are further refinements.

| Adaptive management, also known as adaptive resource management or adaptive environmental assessment and management, is a structured, iterative process of robust decision making in the face of uncertainty, with an aim to reducing uncertainty over time via system monitoring. |

Above definition from Wikipedia

| Adaptive management is a science-based, structured approach to improving our understanding of the problems and uncertainties of environmental and water management. (Older)

Adaptive management provides a structured approach for adaptation in a context of rapid, often unprecedented, and unpredictable environmental change. Its success depends on support from the larger social, regulatory, and institutional context, or “governance system.” (Newer) |

Above definitions from Delta Stewardship Council

The Delta Stewardship Council holds a forum every two years on Adaptive Management. This year, the forum delves into governance. Presenters and participants are from Delta governments and those who would like to participate in Delta government. Topics include equitable adaptation, governance systems and needs, and human dimensions of adaptation and governance.

While that all is nice, it is not what I am looking for to manage the Delta ecosystem. I am more for the older definition. We need answers.

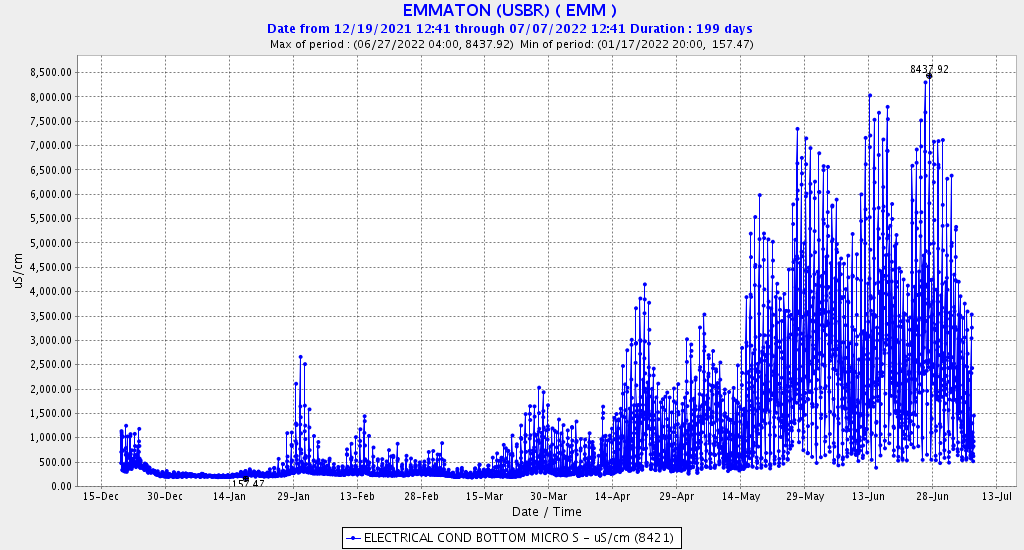

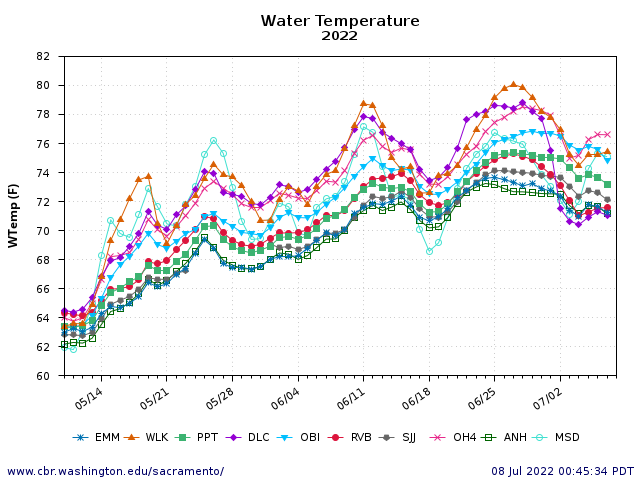

Why are the Sacramento River and Delta so warm in the past decade or so? Is it all climate change, drought, and air temperatures? What has changed, and what can be done about it? Those are my questions. We need more adaptive management questions and some scientific experiments and monitoring. I have analyzed much of the available data and developed theories on causes (with supporting data and analyses), but theories need testing through controlled scientific study that can lead to effective changes: adaptive management.

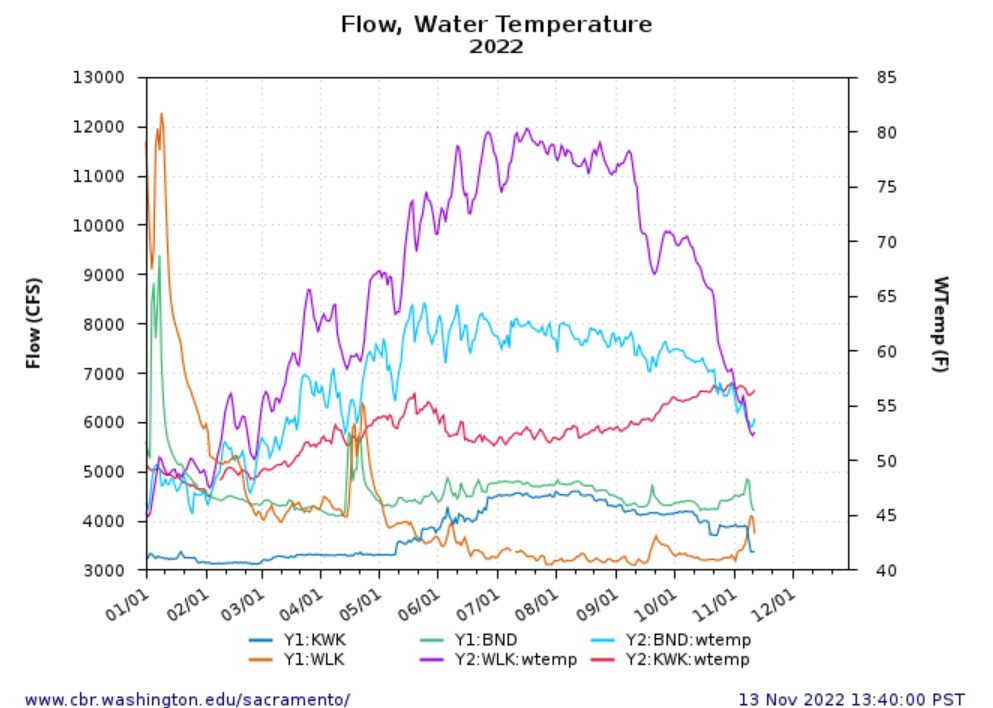

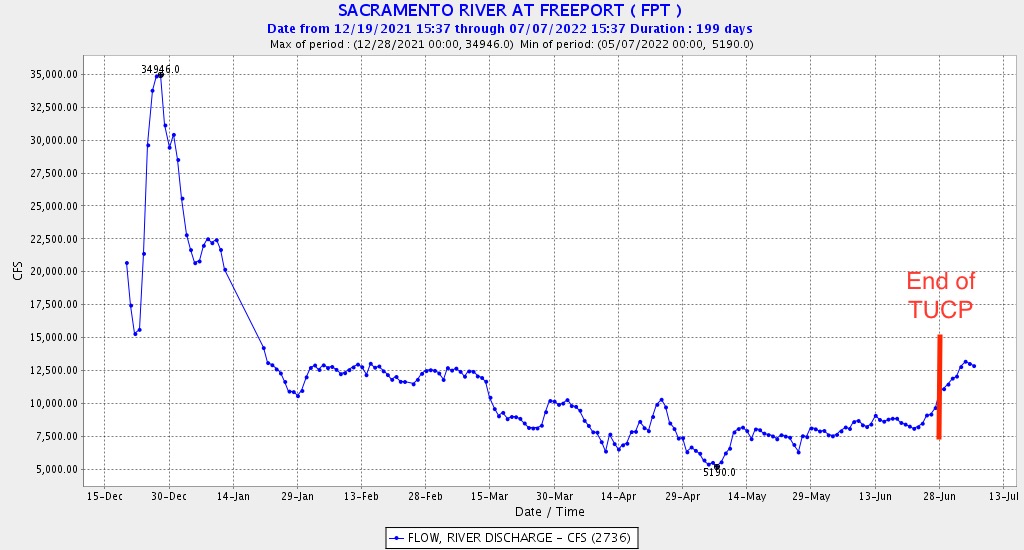

My theory is that we need 5000 to 10,000 cfs streamflow in the Sacramento River to keep it cool in summer. We need to test that theory to find out how much water is really needed, and how much, when, and where under highly variable air temperatures.

Water managers have consistently opposed this kind of experiment. They refuse to use the water for this kind of experiment. And more importantly, they refuse to do an experiment that might produce the answer they don’t want to be known, let alone supported by rigorous study: more flow is needed.

On the contrary, there is a constant, built-in bias towards “experimenting” with how little water one can use to achieve biological objectives. If too little water won’t achieve the desired outcome, managers, and in some cases scientists, try modifying the threshold biological objectives.

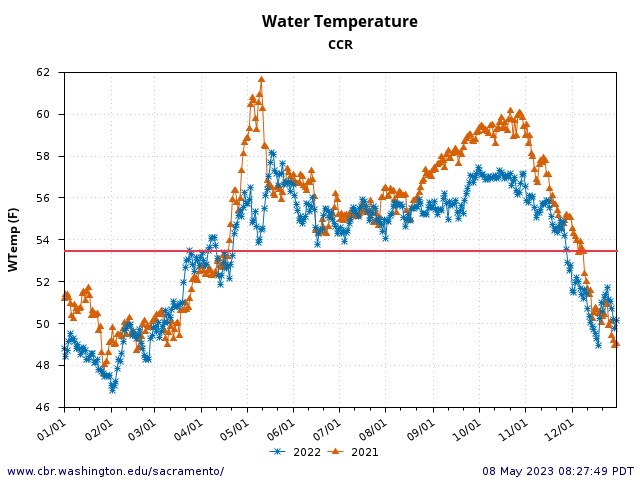

56oF was supposed to be fine for salmon spawning near Redding. In 2021 and 2022, agencies including Reclamation thought they could get away with 58-60oF for periods (they couldn’t, Figure 1). It turns out from controlled experiments that 56oF was too warm – 53oF is needed to keep eggs alive and well in the gravel. There is simply no getting around it. The agencies were experimenting with critically endangered salmon with poorly designed, un-scientific management strategies.

In the Vernalis Adaptive Management Program in the early 2000s, ten years of experimenting found that relatively small increments of flow increase in the San Joaquin River from mid-April through mid-May, combined with minimum Delta exports by the state and federal water projects, did not dramatically increase survival of San Joaquin River juvenile salmon migrating downstream. The “adaptive” element of adaptive management did not thereafter increase the flows to see if that would improve juvenile survival. On the contrary, water managers declared that more flows don’t help, and the Bureau of Reclamation since 2011 has serially ignored the flow requirements and export restrictions in mid-April through mid-May to which the rules were supposed to revert after the “experiment” concluded.

Here are some further questions that are begging for controlled scientific experiments, associated monitoring, and adaptive action:

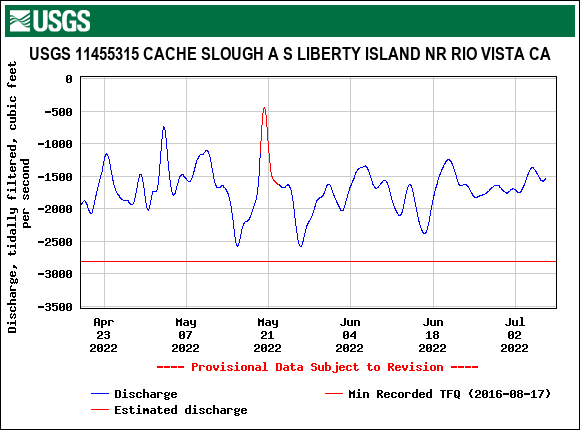

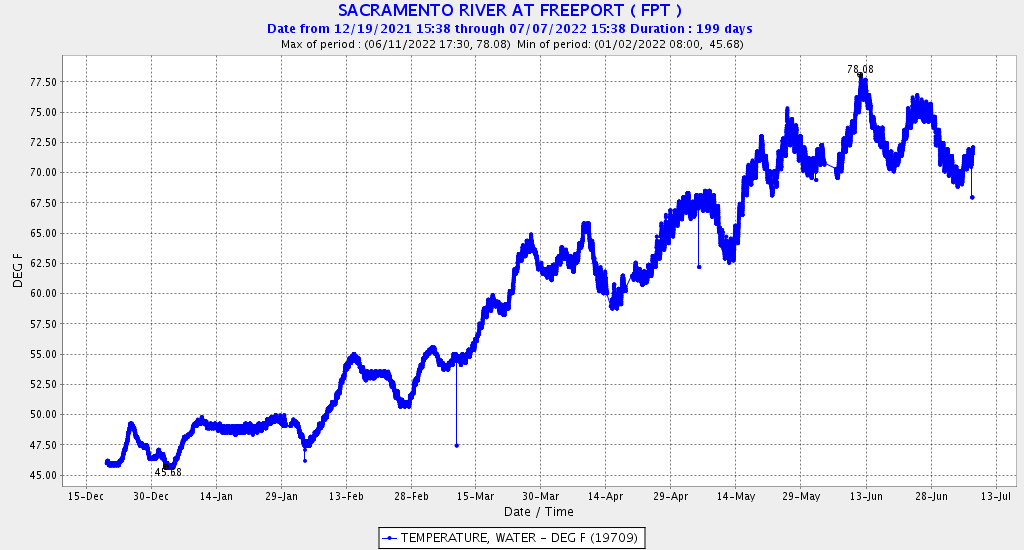

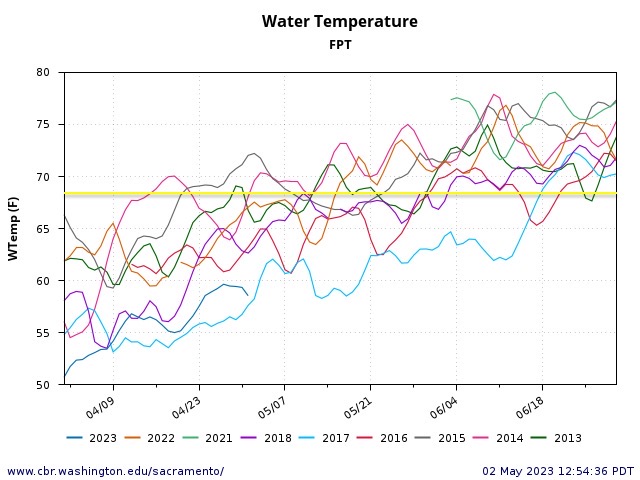

What will it take to keep the spring-summer Delta water temperature in key areas (such as the low salinity zone) below 72oF, at least through spring (Figure 2)?

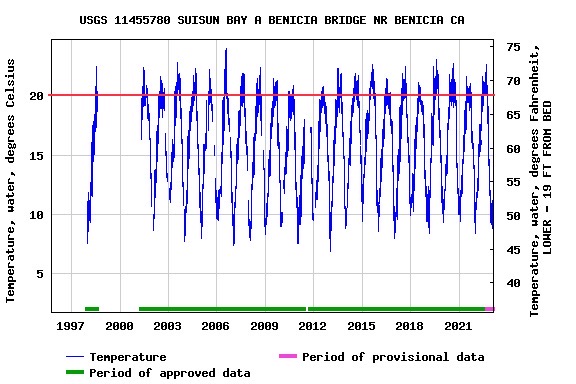

Is there something we can do to keep the Bay cooler in summer (Figure 3)?

There is little doubt that improving these temperatures would improve conditions for fish. But the scientific community needs to push itself and water managers past built-in biases in order to evaluate the feasibility of such improvements.

Figure 1. 2021 and 2022 water temperatures in the Sacramento River above the mouth of Clear Creek near Redding. Red Line is safe level for salmon eggs.

Figure 2. April-June water temperatures in Sacramento River at Freeport in the north Delta in spring in past decade. Yellow line is critical level 68oF for migrating juvenile and adult salmon.

Figure 3. Water temperatures at the Benicia Bridge at the west end of Suisun Bay, 1998-2023. Red line is critical level for salmon survival during migration.