I have studied American shad, a popular sportfish and anadromous herring native to the East Coast, in the Hudson, Columbia, Sacramento, American, Feather, Yuba, and Stanislaus rivers. I have also fished for them for 50 years. They are the most abundant anadromous fish in the Bay-Delta and Columbia River watersheds. Millions run up the Sacramento and Columbia rivers every spring to spawn. The 1-to-6-pound adults arrive in spring and spawn from late spring into summer as waters warm. After spawning, some die, but many adults return to the ocean. The eggs are large like those of salmon, but. unlike salmon eggs, shad eggs float and hatch as they drift downstream toward tidewater in the Delta through late spring and summer. Young shad then rear in the tidal estuary through the summer before heading to the ocean.

Shad interact with our native fish in various ways, most of which are detrimental. Whether they and other nonnative fish like striped bass contribute to population declines of native species like salmon, steelhead, smelt, and sturgeon is open to debate. I believe that coupled with changes in climate and water management, the effects of nonnative fish on native species are getting worse.

A 2017 review of the ecological role of American shad in the Columbia River (Haskell 2017) provided three hypotheses regarding the Shad’s effect on Columbia River food webs:

- Juvenile shad are an abundant and highly energetic food that increase the growth rate of major salmon predators [e.g. Northern Pikeminnow, Walleye, Smallmouth Bass, and Channel Catfish) – viewed as negative by supporting production of salmon predators.

- Juvenile shad are planktivores that compete with juvenile salmon, particularly later migrating sub-yearling Chinook Salmon in the lower Columbia River – viewed as negative by reducing food for salmon thus reducing growth and survival.

- Large numbers of adult shad could influence nutrient balances given their capacity to convey marine-derived nutrients – another source of marine carbon input viewed as positive.

I would add four further hypotheses/issues on the role played by American shad:

- Adult shad migrate from the ocean into the Bay-Delta estuary in spring on their way to spawning rivers. They number in the millions, feeding on plankton including larval fish such as newly hatched Longfin and Delta smelt, and fry salmon that frequent the estuary and lower rivers.

- Adult shad spend late spring and most of the summer spawning in major in the mainstem rivers and their larger tributaries, during which they feed on aquatic invertebrates and juvenile salmonids. Their spawning run in the spring coincides with the rearing of juvenile fall-run salmon and steelhead. Shad adults can be extremely abundant during the spring emergence of fry steelhead, especially in tailwaters below dams that block shad migrations. The American, Feather, Yuba, and Mokelumne Rivers have such conditions. Historical anecdotes of adult shad feeding on young salmonids below the Red Bluff Diversion Dam in the upper Sacramento River are available from CDFW predator survey reports. In my own experience, I commonly use small spoons representing salmonid fry and parr size (2-3 inches long) that are readily swallowed by feeding adult shad.

- Adult shad may spawn through the summer in some tributary tailwaters where cold water releases (<65ºF) are prescribed for over-summering salmonids. Cold water can extend the period of shad spawning and the period in the tidal estuary when juvenile shad compete with smelt and other fishes for zooplankton prey.

- Juvenile American shad rear in freshwater and low-salinity tidal zones of the Bay-Delta estuary from late spring through summer (Figures 1-6), where they feed on zooplankton of the same types as Delta smelt and other native fishes.

As is the case with many native fish species, American shad populations suffer during periods of drought. This has been especially true in the past two decades in the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary (Figure 7), commonly referred to as the period of the Pelagic Organism Decline. It is an open question whether the American shad are simply experiencing the decline like the native fish, or contributing to the native declines, or both.

The likely answer is both. All the fish suffer in drought. All the fish do not recover completely after droughts. All the fish populations exhibit a long-term downward population spiral. For some, it is a spiral toward extinction. Even in decline, some nonnatives like American shad and striped bass can have increasing effects on the natives facing extinction. If that is the case, then we should do everything possible to at least provide habitat conditions that favor native fish over nonnative fish. The fact is that, in many cases, nonnative fish, including shad and striped bass, are more resilient than the native fish. That is because the physical habitat and water management increasingly are less favorable to the native species. We need to reverse this trend.

For more recent discussion on Central Valley American shad see:

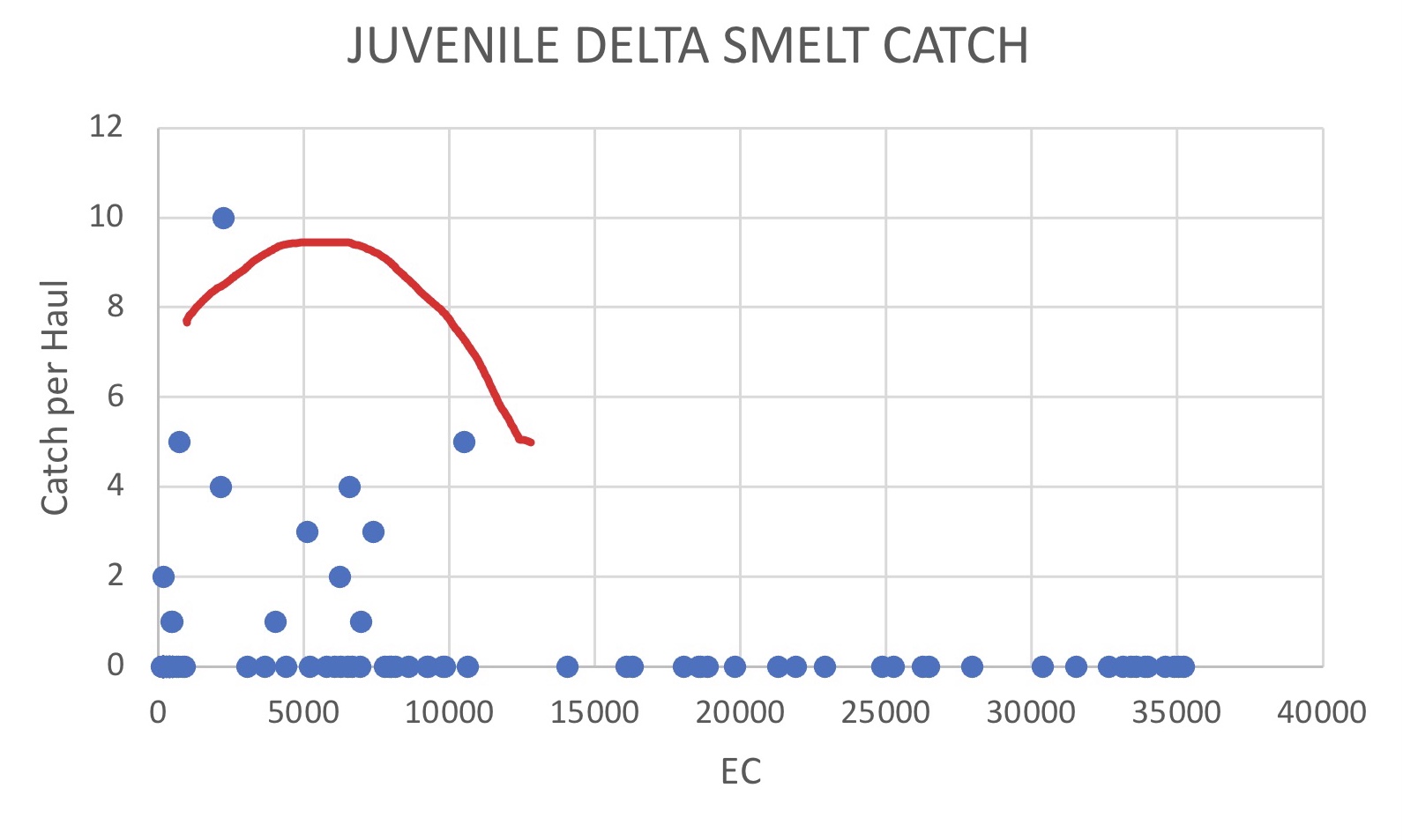

Figure 1. Wet year 2019 American shad juvenile catch-size distribution in Bay-Delta spring 20-mm Survey.

Figure 2. Wet year 2019 American shad juvenile catch-size distribution in Bay-Delta Summer Townet Survey.

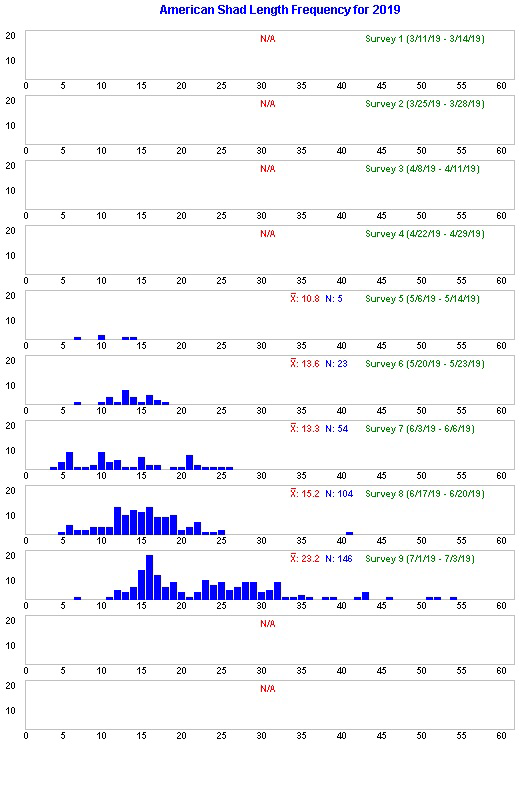

Figure 3. Wet year 2019 salvage and export rates of juvenile American shad at south Delta export facilities.

Figure 4. Wet year 2019 catch distribution of juvenile American shad in September Fall Midwater Trawl Survey.

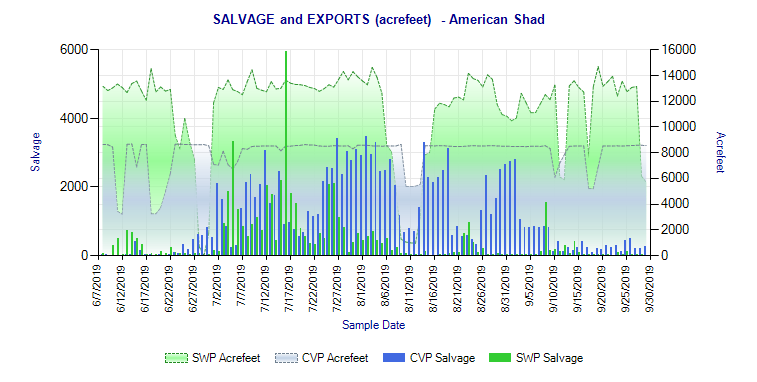

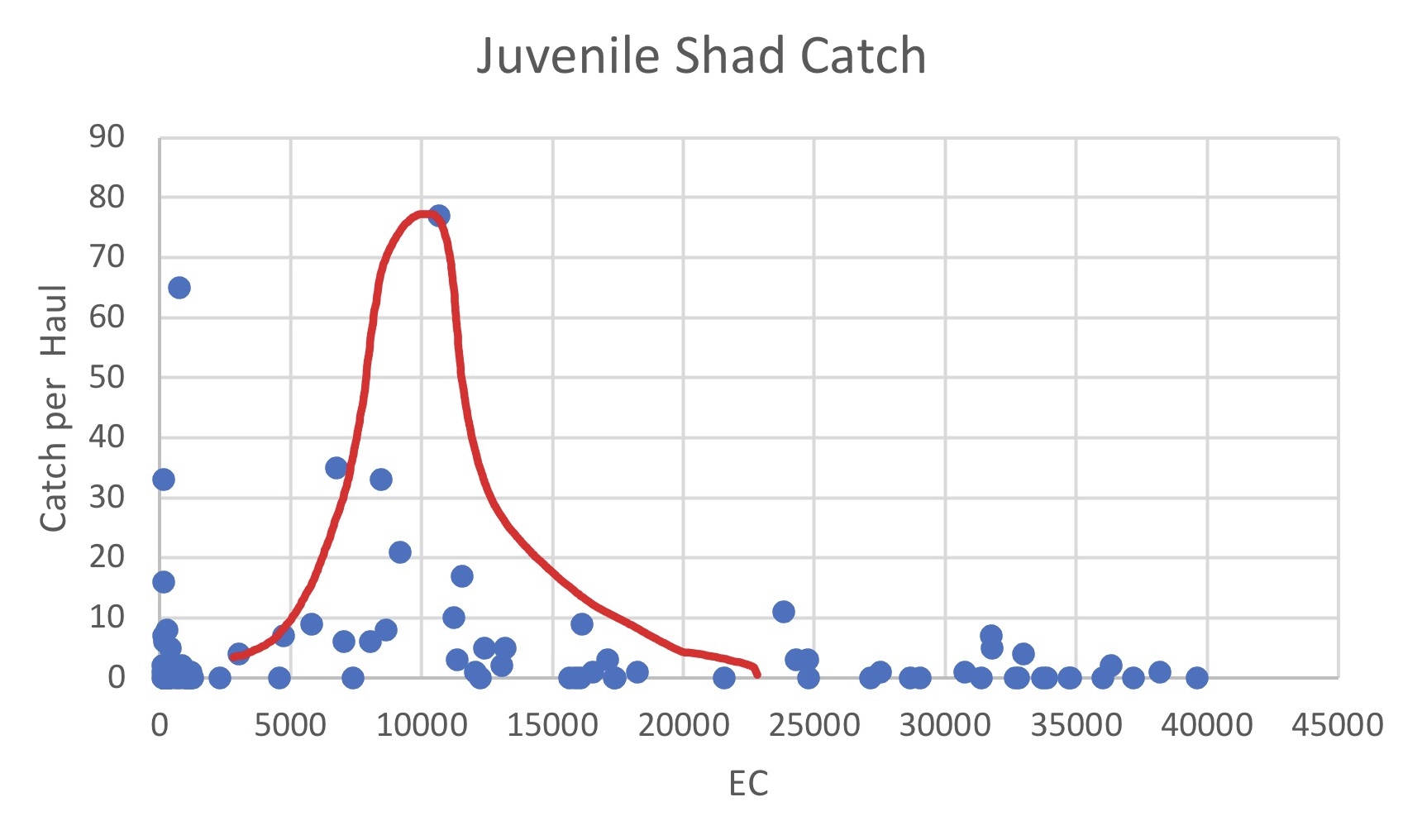

Figure 5. Wet year 2019 American shad catch distribution versus salinity (EC) for September Fall Midwater Trawl Survey. Red line indicates shad concentrate in low-salinity zone (5-15k EC).