In 1992, the Central Valley Project Improvement Act (CVPIA) was enacted by Congress and resulted in the development of an Anadromous Fish Restoration Program (AFRP) to double the anadromous fish populations in the Central Valley by 2002. Astoundingly, after twenty-three years and more than $1,000,000,000 spent, extensive monitoring studies and the use of alleged “adaptive management”, the salmon runs have not only not doubled in size, but have declined. Most notably, there is no measureable progress toward delisting any of the threatened or endangered anadromous fish, and the fall-run Chinook, the most abundant among the four salmon runs, have now dropped even further from historical levels. Some individuals have even recently suggested that the fall run may warrant listing as an endangered species (Williams 2012) … not exactly a glowing success story for salmon restoration (or an efficient expenditure of money).

Because of this poor track record, an independent peer review (“Listen to the River”) of the CVPIA fisheries program was conducted in 2008 and was highly critical of the government agencies’ implementation of the anadromous fish restoration efforts. For example,

“Yet it is also far from clear that the agencies have done what is possible and necessary to improve freshwater conditions to help these species weather environmental variability, halt their decline and begin rebuilding in a sustainable way. A number of the most serious impediments to survival and recovery are not being effectively addressed, especially in terms of the overall design and operation of the Central Valley Project system.” (Cummins et al. 2008)

In particular, the review criticized the failures of implementing an effective, scientifically valid adaptive management program:

“The absence of a unified program organized around a conceptual framework is one of the reasons the program appears to be a compartmentalized effort that lacks strategic planning and decision-making. As a result the program is unable to address the larger system issues, has a disjointed M&E [monitoring and evaluation] program, exhibits little of the traits expected from effective adaptive management, and is unable to effectively coordinate with related programs in the region. An uncoordinated approach also creates boundaries to the free flow of useful information and program-wide prioritization. We observed that most researchers and technicians seemed unclear how or even whether their local efforts related to or contributed to the overall program.” (Cummins et al. 2008)

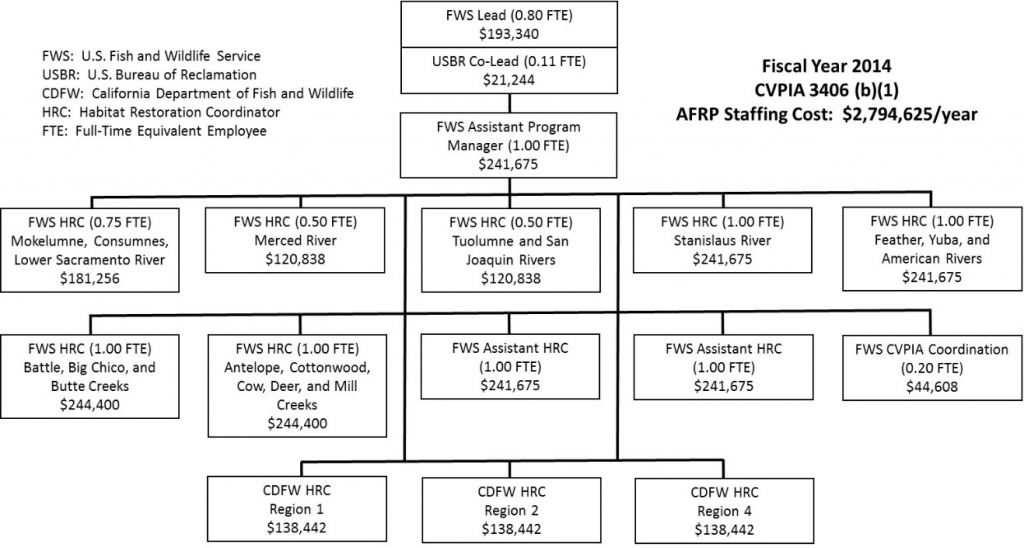

The “Listen to the River” report provided numerous recommendations to improve implementation of the CVPIA AFRP. Included among those suggestions was development and utilization of an effective adaptive management program. Surprisingly, it has now been seven years since the review panel’s report and all proposals put forth remain unimplemented by the involved agencies. When a newspaper reporter recently queried Bob Clarke, fisheries program supervisor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), concerning the lack of progress and excessive funds expended in the AFRP, the response was that officials are still working to change the way they prioritize restoration. Clarke said: “It’s a process, unfortunately it’s not a process that allows you to get your results immediately,”1 Seven years? … It should have been done in seven months. A subsequent Redding Record Searchlight Newspaper Editorial2 on the topic responded that “those responsible have offered excuses, not explanations” and maybe what the AFRP needs “are fewer administrators and more field work”. It’s hard to disagree with that opinion. In an astonishing example, an examination of a portion of the annual AFRP budget in 2014 revealed that a total of $2,794,625 was expended on state and federal staff. Most of those funds were spent on so-called “Habitat Restoration Coordinators”.

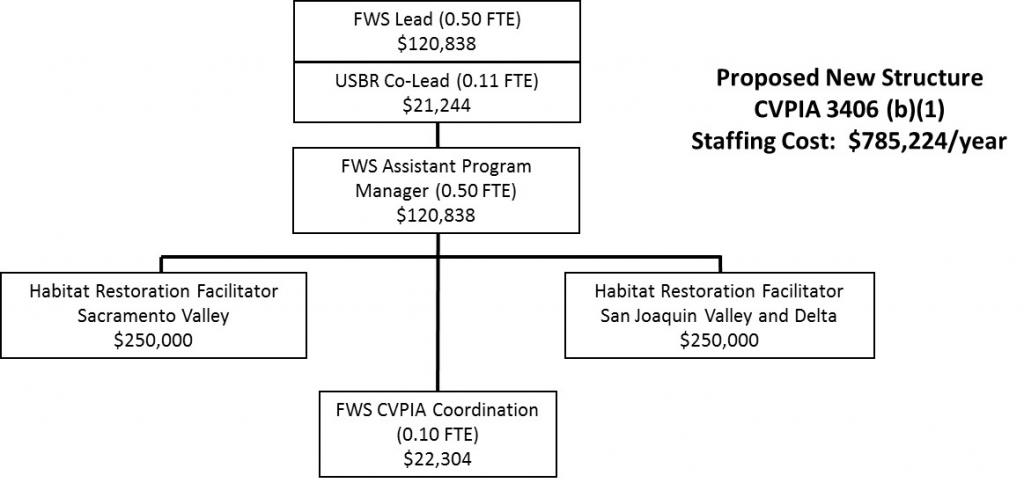

It’s difficult to comprehend how one individual could work 52 weeks a year “coordinating” very few, if any, actual restoration projects in such small regions. Furthermore, with redundancy in the AFRP, both USFWS and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife have “Habitat Restoration Coordinators” overlapping within the same watersheds. Frankly, some of these efforts could probably be handled by an experienced individual during Saturday afternoons and serve as a “facilitator” to expedite projects, instead of a “coordinator” impeding progress with an added layer of bureaucracy. A suggested alternative approach would be to reorganize the program as shown below. This one example would allow more than $2,000,000 to be reallocated to actual salmon habitat restoration projects every year. Many more examples exist.

It’s difficult to comprehend how one individual could work 52 weeks a year “coordinating” very few, if any, actual restoration projects in such small regions. Furthermore, with redundancy in the AFRP, both USFWS and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife have “Habitat Restoration Coordinators” overlapping within the same watersheds. Frankly, some of these efforts could probably be handled by an experienced individual during Saturday afternoons and serve as a “facilitator” to expedite projects, instead of a “coordinator” impeding progress with an added layer of bureaucracy. A suggested alternative approach would be to reorganize the program as shown below. This one example would allow more than $2,000,000 to be reallocated to actual salmon habitat restoration projects every year. Many more examples exist.

Dick Pool, President of Water4Fish and a long-time promoter for salmon restoration, recently summed up the problem: “The CVPIA program needs a major restructuring. For the last ten years, the salmon industry, Congress and many others have advocated the money be spent on ‘On the Ground’ projects in the river and in the Delta which deal with the real problems. So far there has been no change in the program.” After 23 years, it is time to listen to the river, implement a new approach, use true adaptive management, and place the needs of the salmon in front of building larger state and federal bureaucracies.

Dick Pool, President of Water4Fish and a long-time promoter for salmon restoration, recently summed up the problem: “The CVPIA program needs a major restructuring. For the last ten years, the salmon industry, Congress and many others have advocated the money be spent on ‘On the Ground’ projects in the river and in the Delta which deal with the real problems. So far there has been no change in the program.” After 23 years, it is time to listen to the river, implement a new approach, use true adaptive management, and place the needs of the salmon in front of building larger state and federal bureaucracies.

References

Arthur, D. 2015. “$1 Billon Later, Salmon are Still in Peril”. Redding Record Searchlight, May 17, 2015.

Redding Record Searchlight Editorial. 2015. “Agencies finally getting it – fish need cold water.” June 5, 2015.

Cummins, K., C. Furey, A. Giorgi, S. Lindley, J. Nestler, and J. Shurts. 2008. Listen to the River: An Independent Review of the CVPIA Fisheries Program. Prepared for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. December 2008. 51 p. plus appendices.

Williams, J.G. 2012. Juvenile Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in and around the San Francisco estuary. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science 10(3). October 2012.