Previously… Part 1: Central Valley Salmon and Steelhead Hatchery Program Reform

Environmental Factors Affecting Smoltification and Early Marine Survival of Anadromous Salmonids. 1980. GARY A. WEDEMEYER, RICHARD L. SAUNDERS, and W. CRAIG CLARKE1.

“There is reason to suspect that in many cases apparently healthy hatchery fish, though large and silvery, are not actually functional smolts and their limited contribution to the fishery, even when stocked into the same rivers from which their parents were taken, results from their being unprepared to go to sea. This failure to produce good quality smolts probably arises from an incomplete understanding of exactly what constitutes a smolt, as well as from a lack of understanding of the environmental influences that affect the parr-smolt transformation and which may lead, as a long term consequence, to reduced ocean survival.”

This paper is over thirty years old (1980), yet it still rings true. It is most certainly a complicated subject that is an on-going concern in hatchery science and management. There remains room for improvement if funding is available for hatchery program upgrades.

“In the absence of complicating factors such as altered river and estuarine ecology, smolt releases should be timed to coincide as nearly as possible with the historical seaward migration of naturally produced fish in the recipient stream, if genetic strains are similar. At headwater production sites, much earlier release may be called for… The desired result is that hatchery reared smolts which are genetically similar to wild smolts enter the sea at or near the same time.”

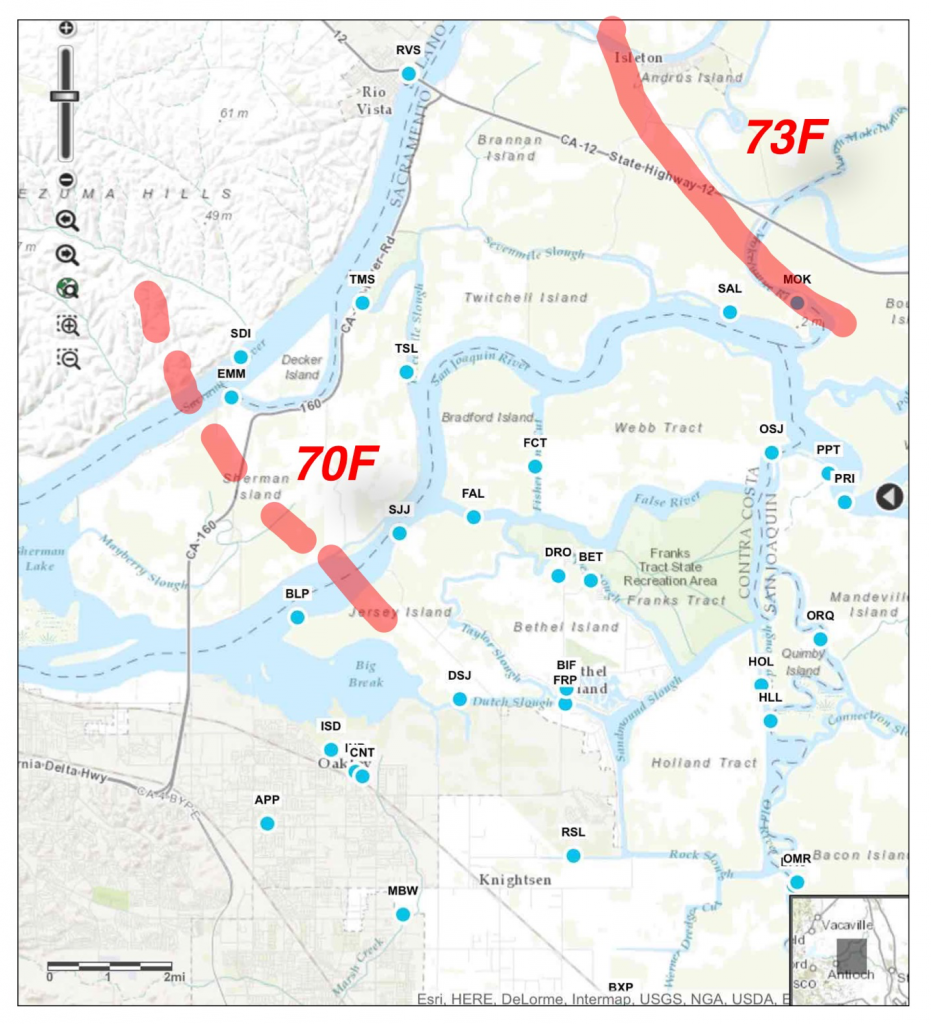

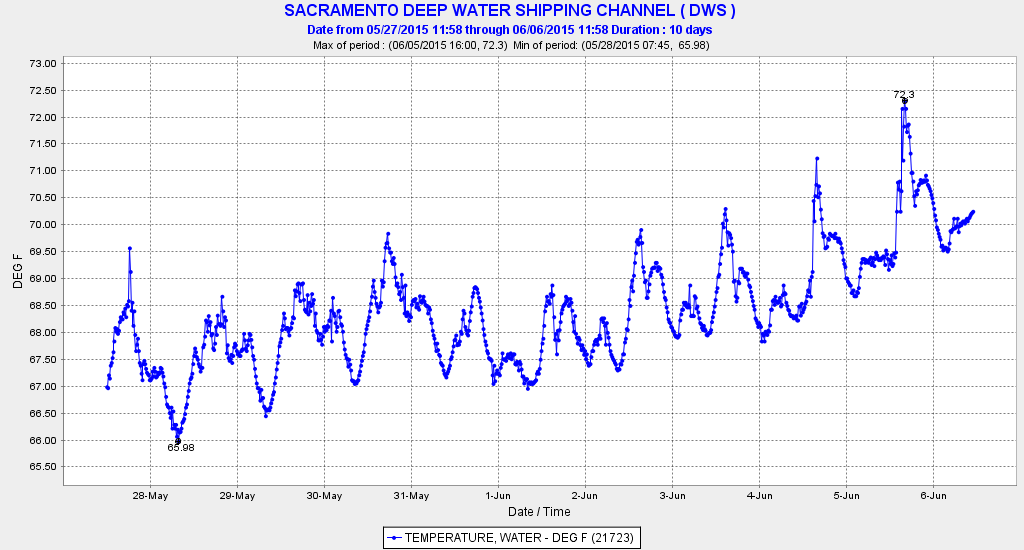

It has been apparent for many decades that Central Valley Fall Run and Spring Run Chinook have a classic “ocean-type” life-history pattern, wherein young spawned in the fall head to the ocean early in their first year rather than as yearlings. Even within the ocean-type, Central Valley Fall Run have two types: one has fry rearing in the estuary (Bay-Delta) and the other in rivers. Of these two types, Valley hatcheries have chosen to manage for the latter. Hatcheries pump out smolts by the millions in April and May, on top of a smaller number of “wild” river-smolts. I believe the “river-smolt” type has been the minority contributor at least since all the dams were built. There simply is not enough river habitat, and what there is has been severely degraded by dams, water management, and physical habitat damage (e.g., levees and land use). The majority contributor is the Bay-Delta or “estuary-smolt” type. Fry that move to the estuary in December-January grow quickly and enter the ocean as smolts in March, a month or more before the river-type. This is a huge advantage for the estuary-type. The hatchery programs could focus more effort on this type by out-planting fry to the estuary or lower river floodplains immediately above the estuary (e.g., Yolo Bypass). Experimental out-planting of hatchery fry to rice fields in the Yolo Bypass has proven promising2. There are also many natural habitats in the lower river floodplains and Bay-Delta that could accommodate out-planting.

This post is part of a 4 part series on hatchery reform, check back into the California Fisheries Blog over the next week for Parts 3 and 4.