In a 9/22/20 post, I suggested summer Delta outflow standards. In this post I suggest a spring-summer water temperature standard for the Delta as further protection for salmon and smelt. Water temperatures above 23oC (73oF) are harmful to salmon and smelt, which live and migrate through the north and west Delta throughout the summer. Much of the Delta smelt population that remains is located in these regions especially in dry years. Spring-run and winter-run salmon migrate upstream through the area in late spring. Fall-run salmon migrate upriver through the summer.

Harm occurs as stress, higher predation, avoidance reactions, poor growth, and reduced long-term survival and reproduction. At higher temperatures (>23oC) migration blockage and mortality occurs. Such temperatures are commonly reached or exceeded in the north Delta even in wetter, water-abundant years.

High water temperatures occur in the Delta when there are high air temperatures and/or low freshwater inflow and outflow. Such conditions are becoming more frequent with climate change. A good example occurred in water year 2020, which featured low precipitation, low snowpack, and high air temperatures. Because water managers cannot control air temperatures or watershed precipitation, they must manage Delta inflows from reservoir releases and outflows through the Delta to improve water temperature control in May-September, especially in drier years.

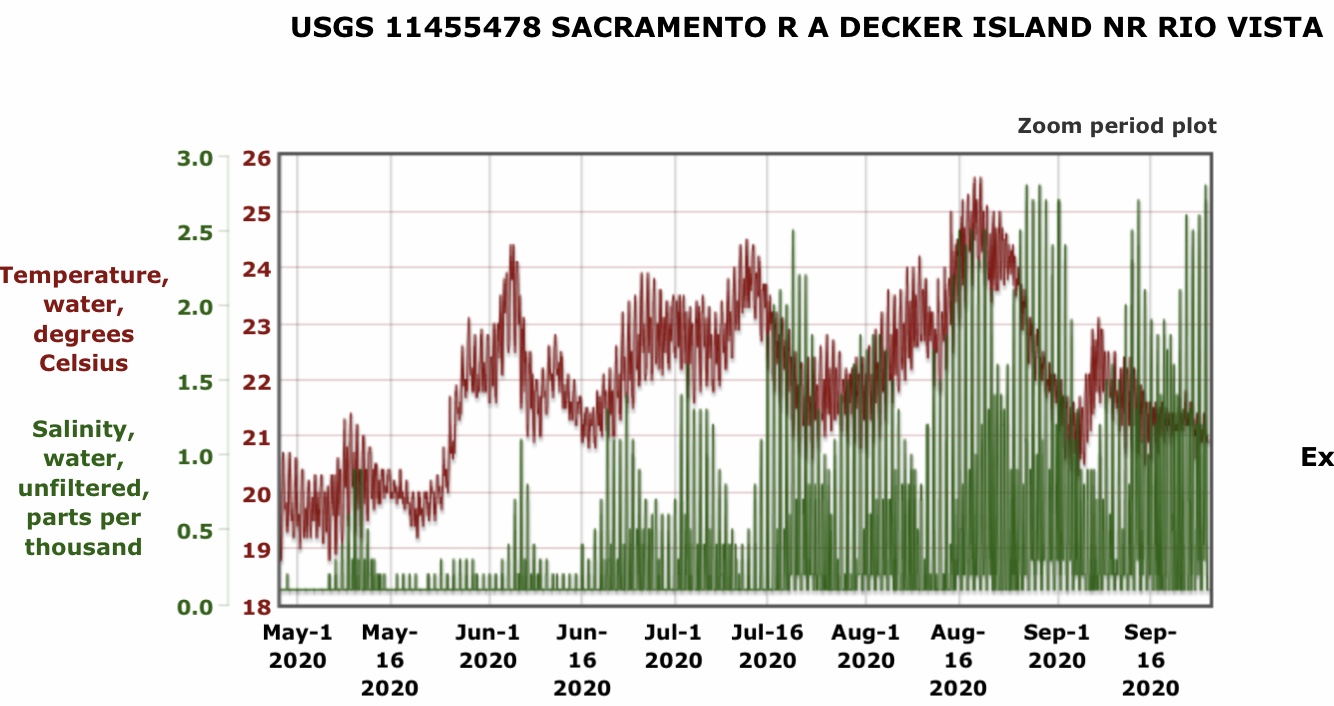

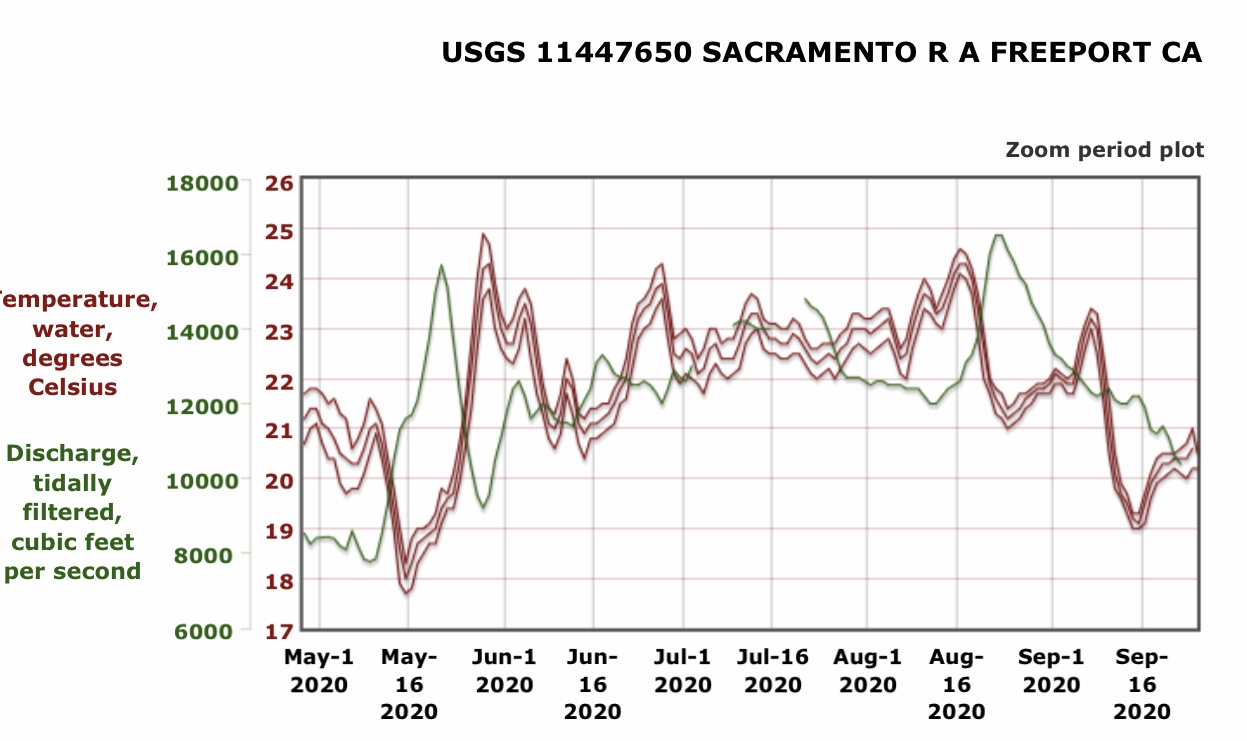

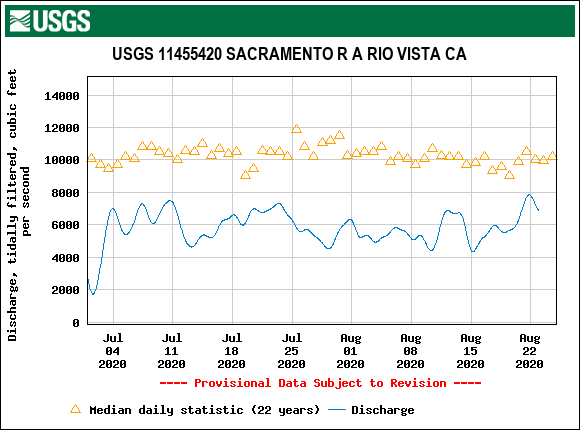

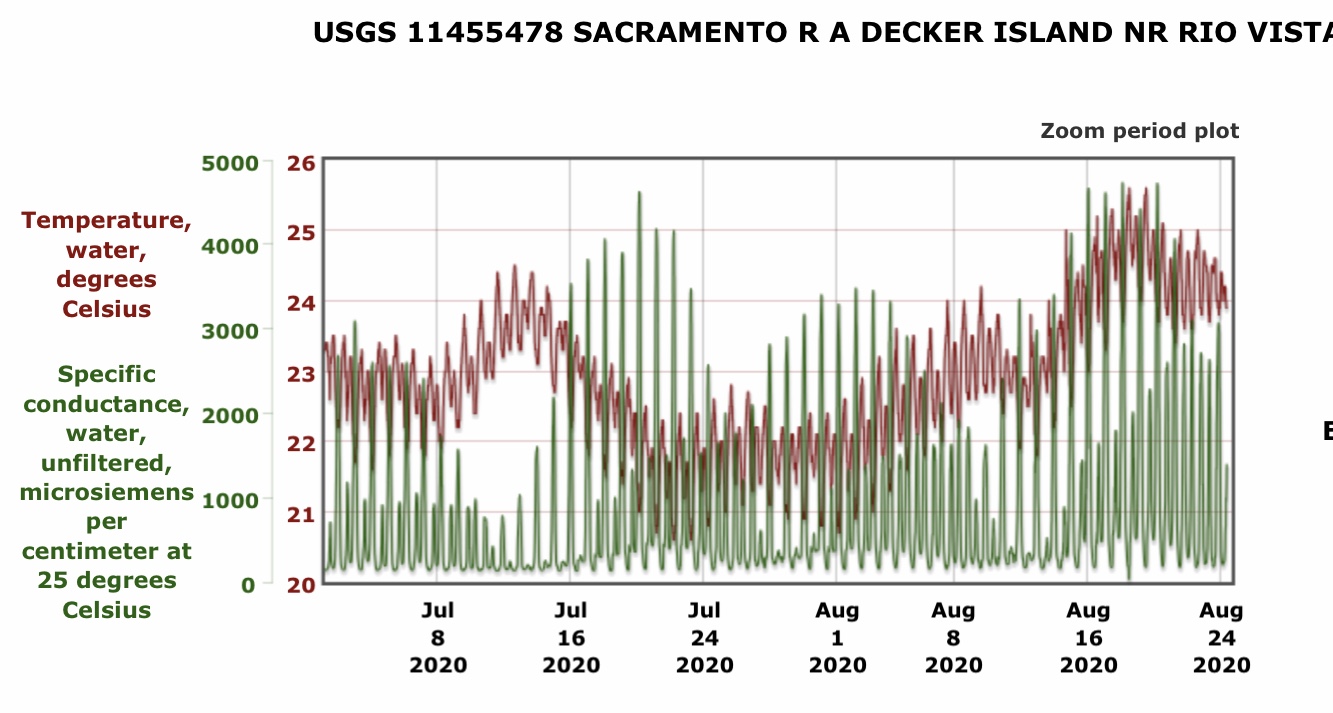

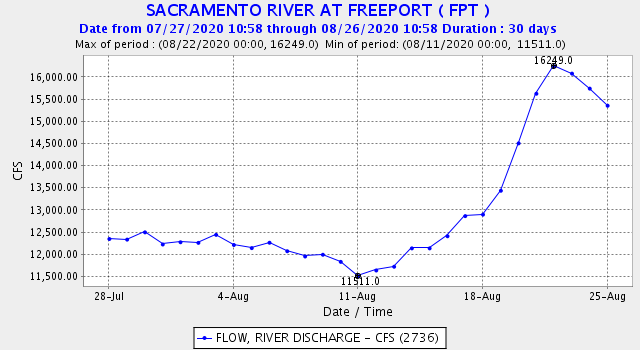

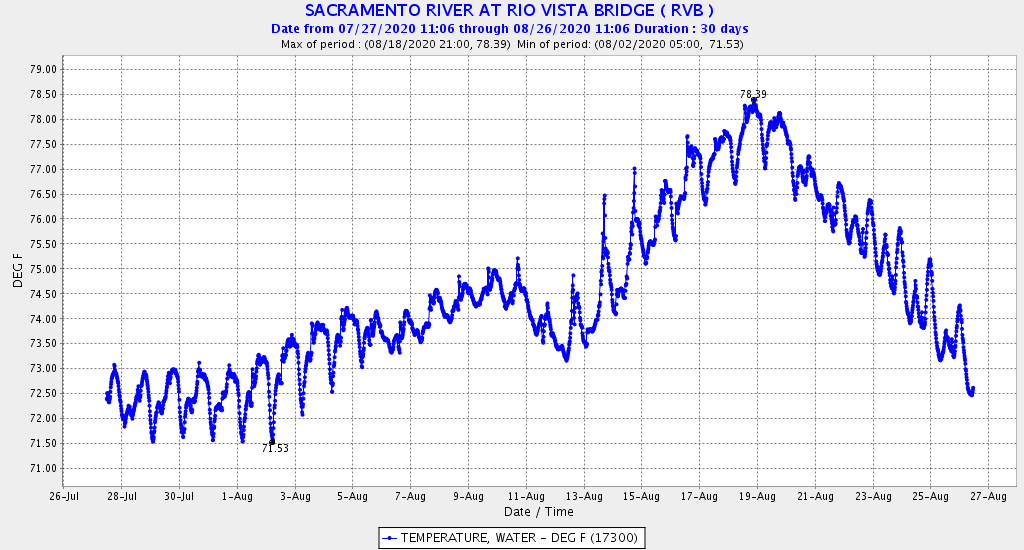

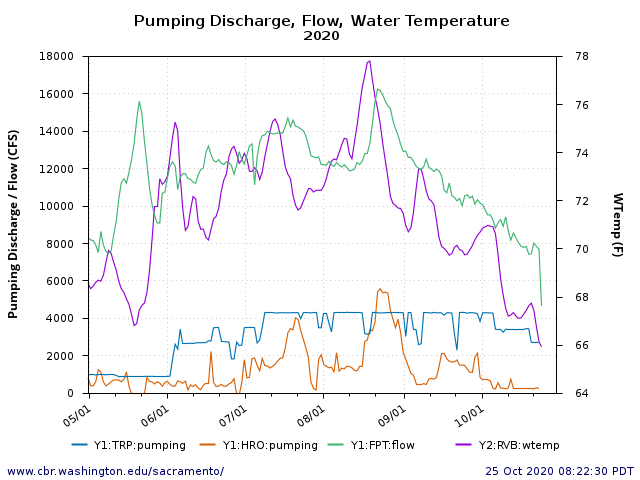

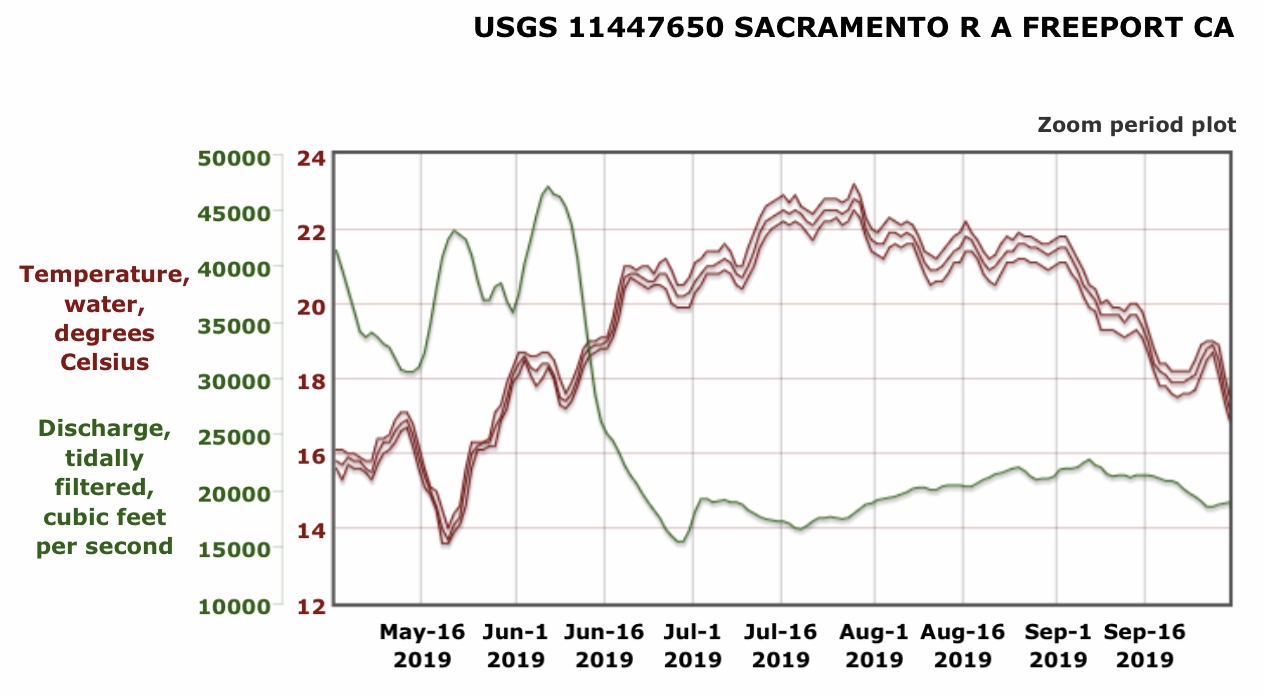

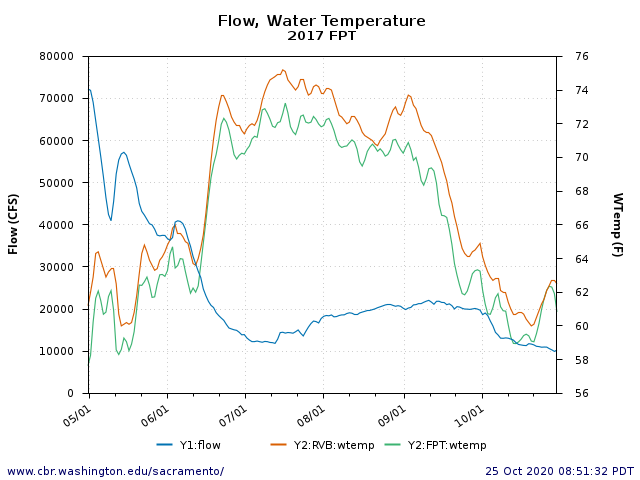

To protect smelt and salmon, there need to be reasonable water temperature standards in the Delta. The existing water temperature standard in the lower Sacramento River above the Delta is 68oF, but managers of the state and federal water projects pay it almost no heed. There is no existing standard for the Delta. The north Delta water quality standard for the Sacramento channel in wet years should be 70oF (21oC) at Freeport and at Rio Vista. In normal and dry water years, the standard should be 72oF (22oC) at Freeport and at Rio Vista. In critical drought years, the State Water Board needs to require additional Delta inflow and curtail exports as needed to respond to extreme events (e.g., water temperatures greater than 75oF during heat waves). At critical times, a change of only a degree or two will help limit fish stress and mortality.

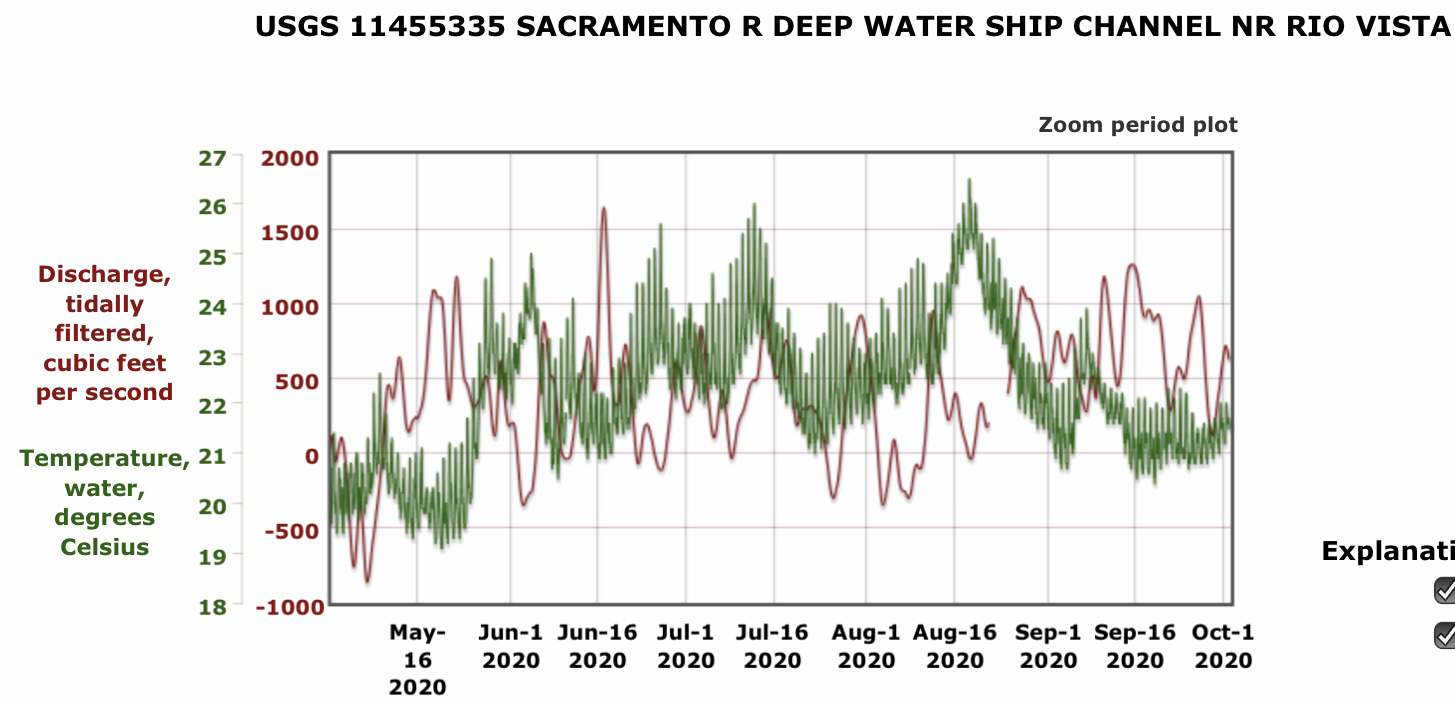

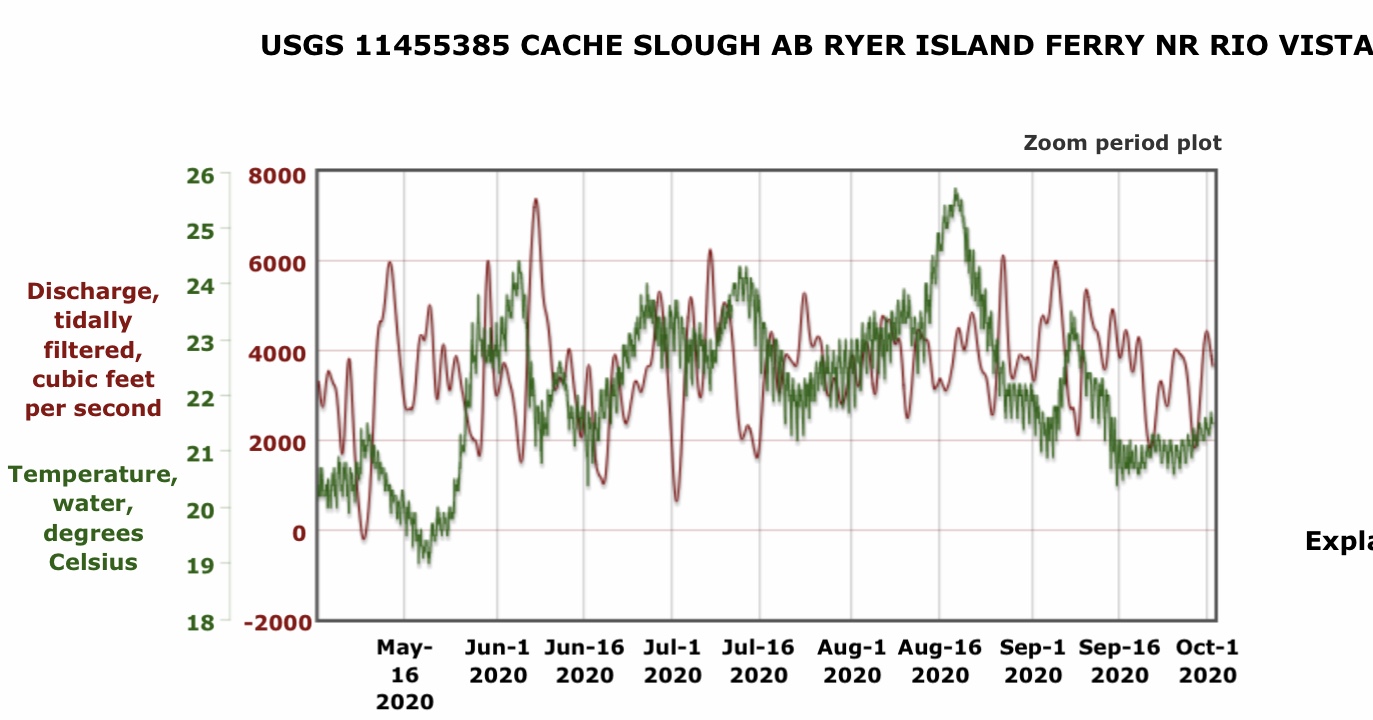

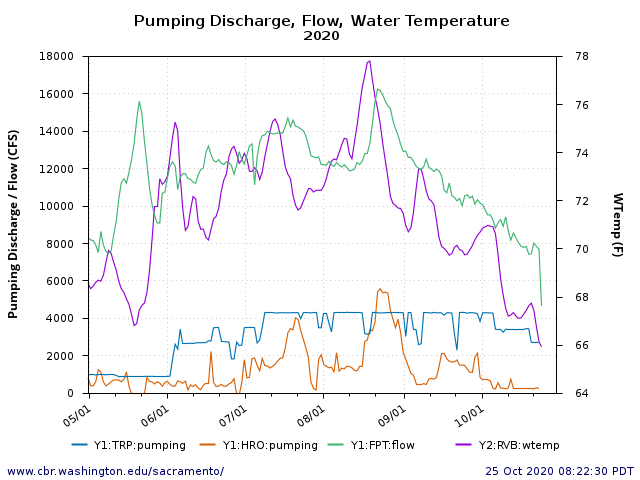

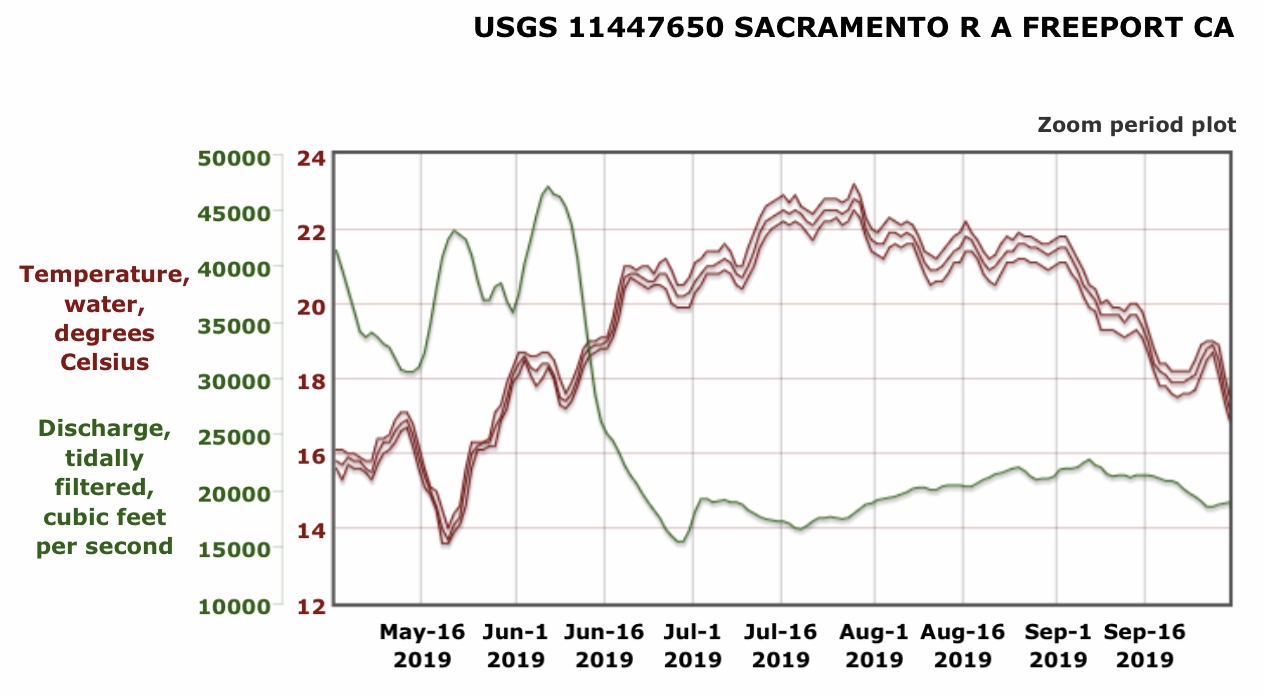

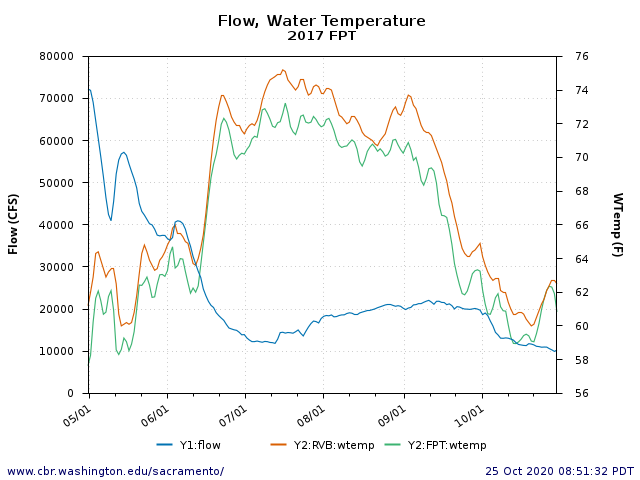

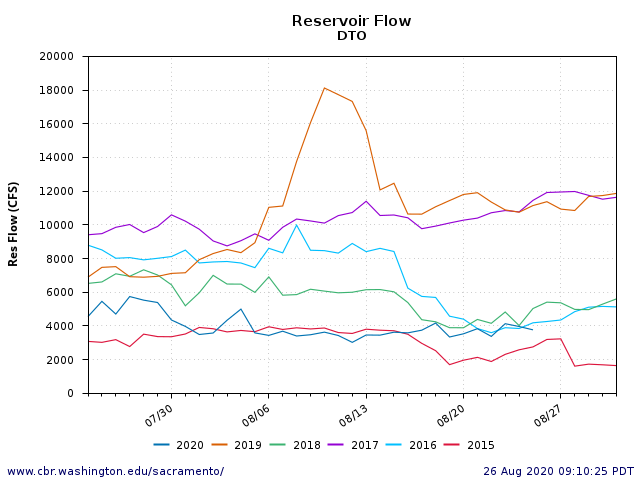

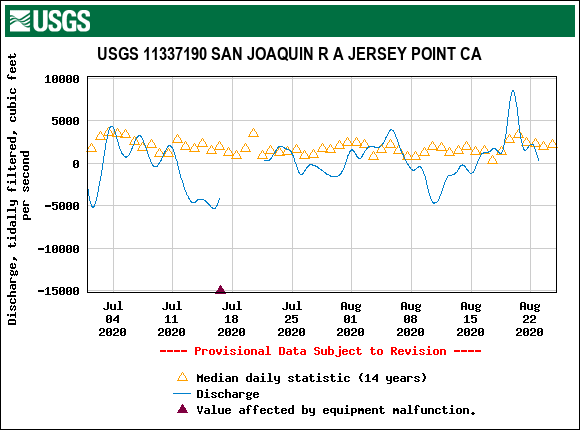

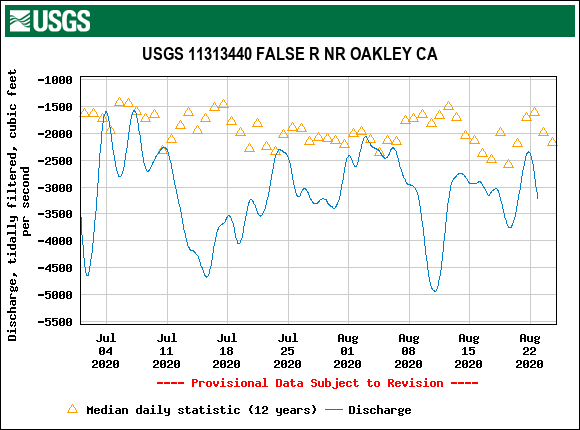

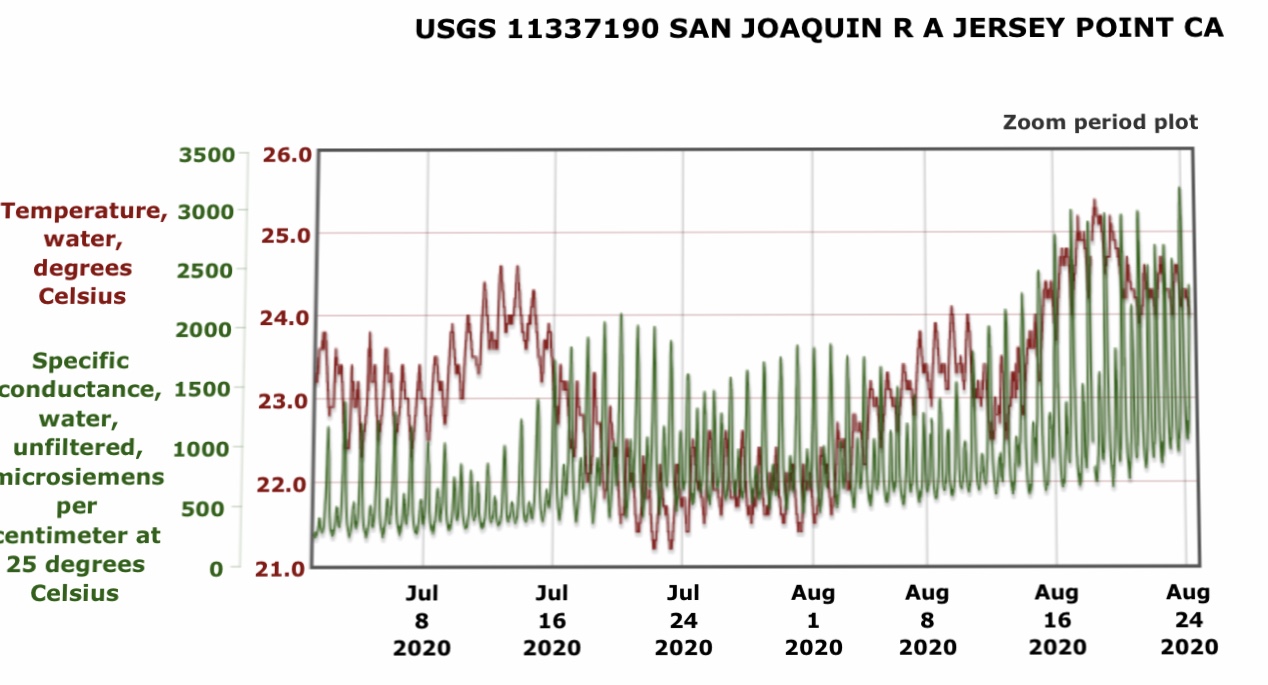

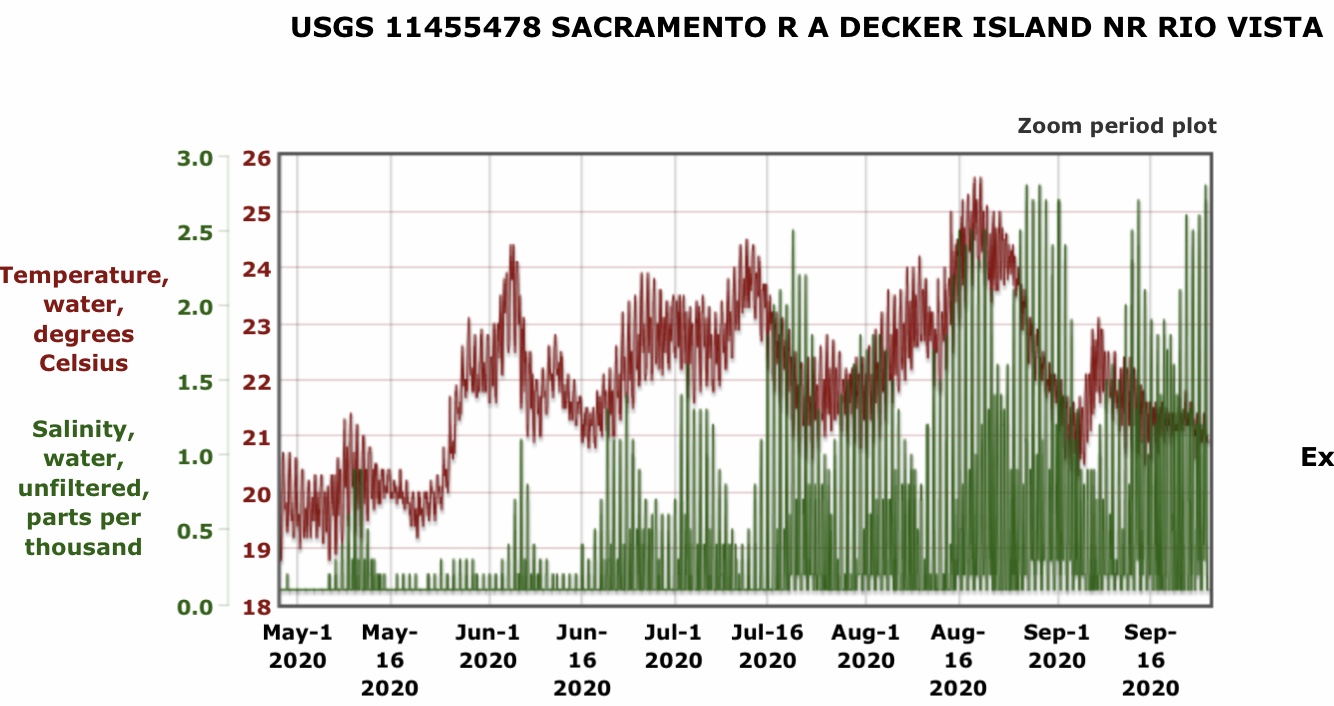

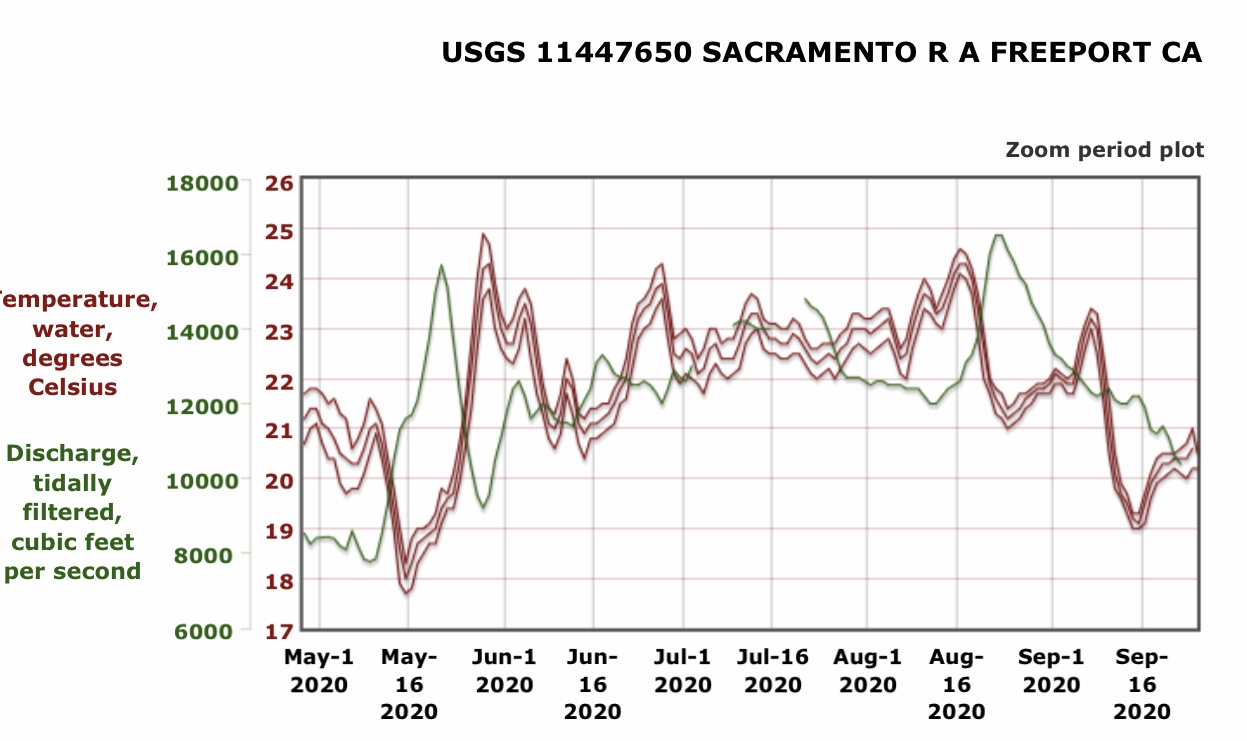

Higher Delta outflow and lower exports are appropriate prescriptions for maintaining reasonable water temperatures in the Delta (see Figures 1-3 and caption notes). For example, in July and August 2020 (Figures 1-3), increased inflow into the 14,000-16,000 cfs range from 12,000 cfs at Freeport could have held water temperature below 22oC. Note in Figure 3 that increased inflow can be captured by south Delta exports (Figure 3). However, during heat waves under extreme drought conditions, the State Board should also limit exports to retain outflows from the Delta to keep the low salinity zone out of the warmer Delta. Otherwise, exports will reduce the portion of Delta inflows (Freeport flows) that reach Rio Vista.

Such standards are achievable, albeit at significant water supply cost. They are worth the effort. High summer water temperatures, such as those that occurred in wet year 2019 and dry year 2020, must be mitigated. The 23-25oC conditions in summer 2020 (portrayed in Figures 1-3) should not occur, and would not under the suggested Delta water temperature standard. For wet years such as 2019 (Figure 4) and 2017 (Figure 5), water temperatures should be kept at or below 70oF (21oC) by maintaining Freeport near 20,000 cfs as needed.

In summary, Delta water quality standards should be adopted for inflow, outflow, and water temperature to protect salmon and smelt in the warmer months of the year, May-September. Such standards are needed because of recent changes in water project operations and the effects of climate change.

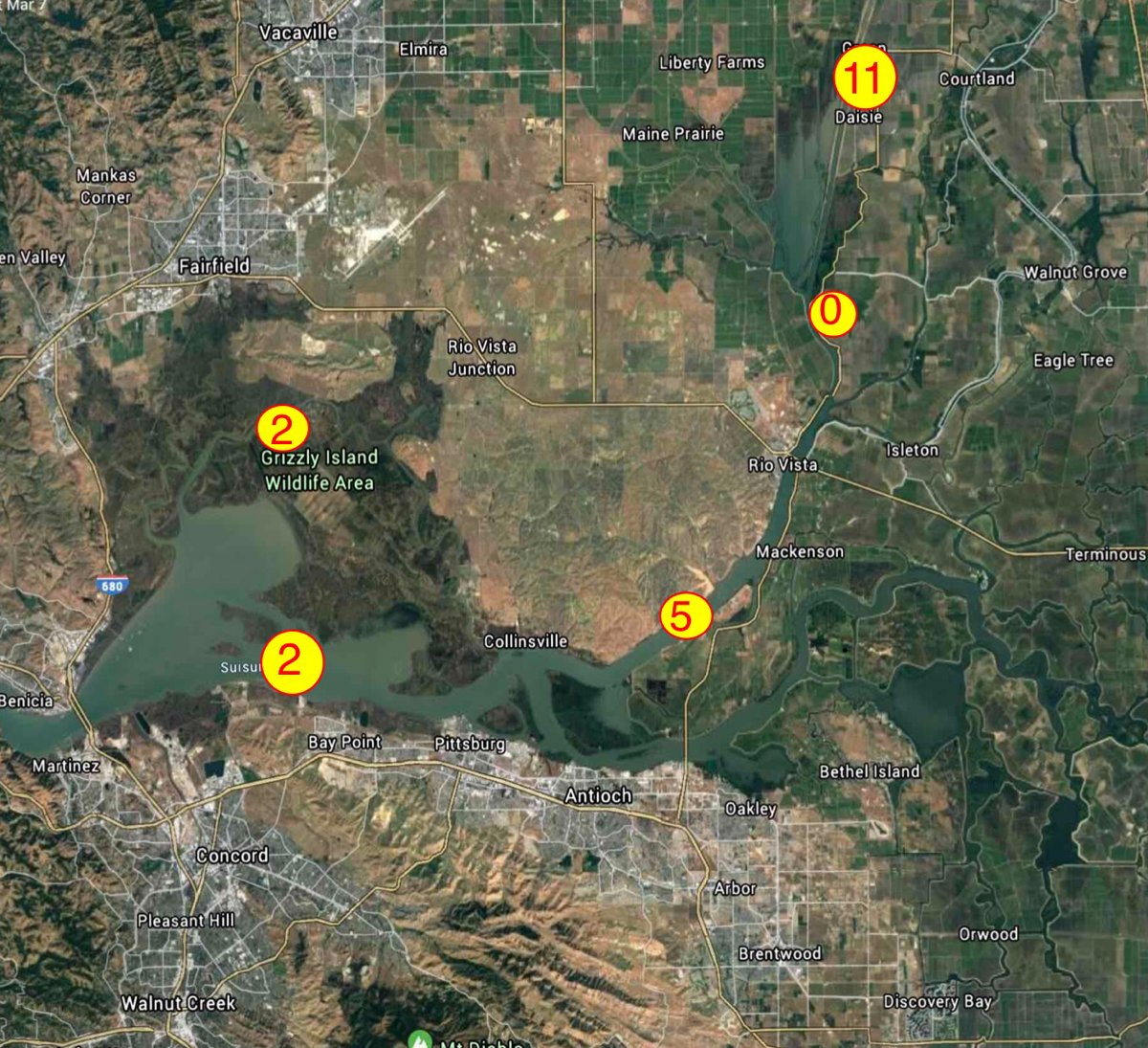

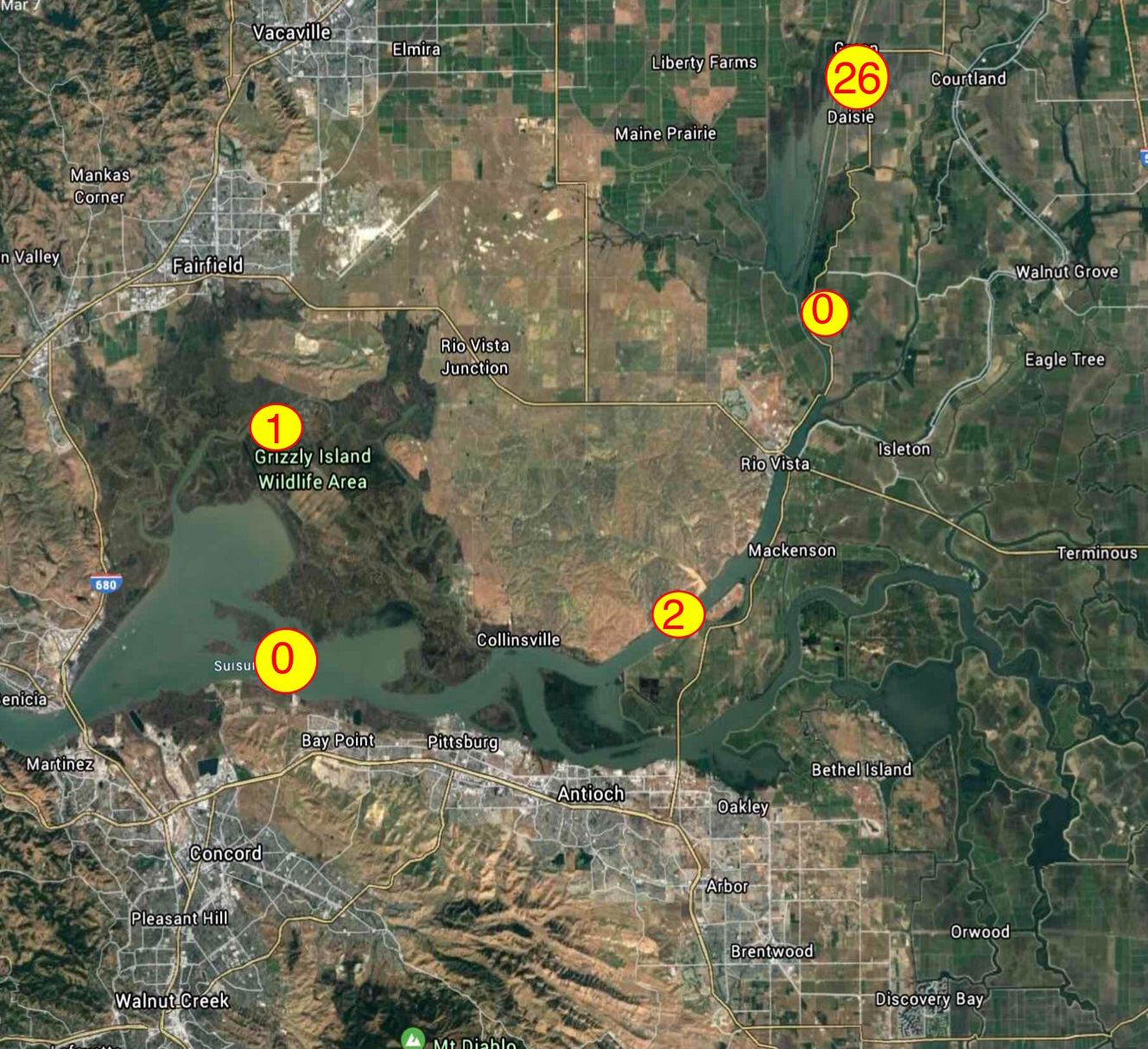

Figure 1. Water temperature and salinity in the west Delta near Rio Vista in spring-summer 2020. Note Delta draining in neap-tide periods generally brings warmer water downstream into the west Delta, except in mid-August event when a heat wave drove water temperatures up into 23-25oC range. This event was accentuated by higher exports and associated high Delta inflows.

Figure 2. Water temperature and net river flow (tidally filtered) in the lower Sacramento River at Freeport in the north Delta in spring-summer of dry year 2020. Note that it took flows at or greater than 16,000 cfs to keep temperatures near 70oF (21oC).

Figure 3. Sacramento River flow at Freeport (FPT), water temperature at Rio Vista (RVB), and south Delta exports at Tracy (TRP) and Banks (HRO) pumping plants in south Delta from May-Oct 2020.

Figure 4. Water temperature and net river flow (tidally filtered) in the lower Sacramento River at Freeport in the north Delta in spring-summer of wet year 2019. Note that it took flows at or greater than 16,000 cfs to keep temperatures near 70oF (21oC).

Figure 5. Sacramento River flow at Freeport (FPT-Y1) and water temperature at Freeport (FPT-Y2) and Rio Vista (RVB-Y2) from May-Oct 2017.