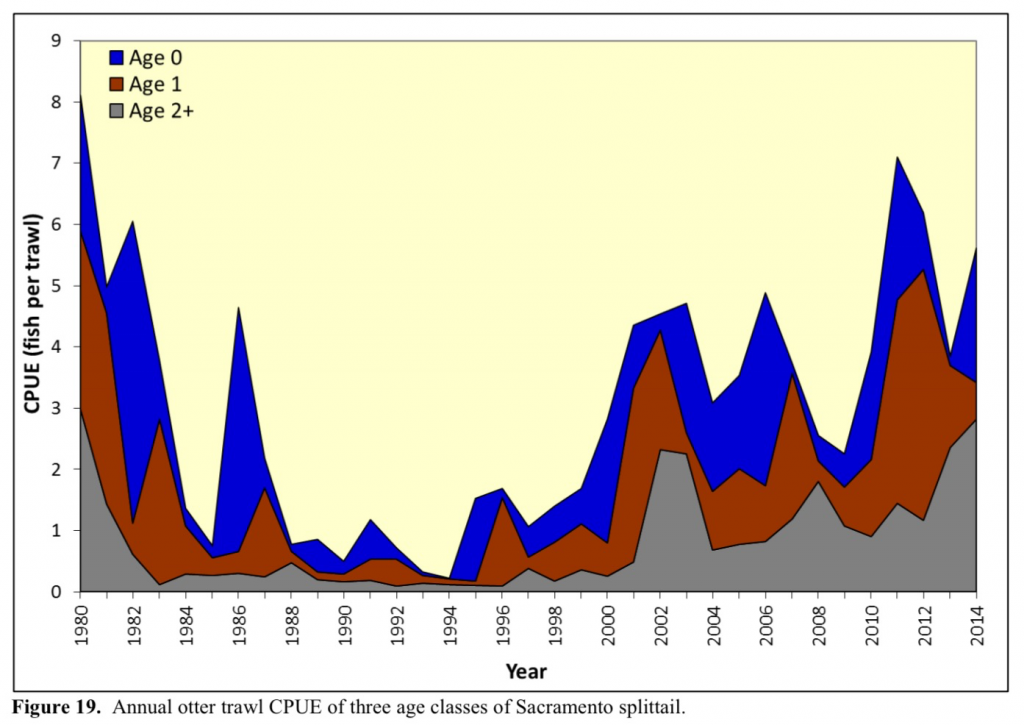

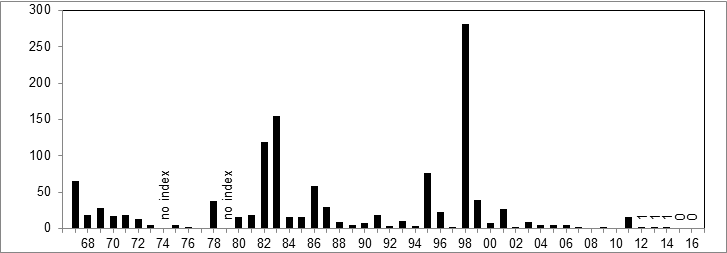

Though it is counter-intuitive in a flood year, fish salvage has become a real problem this spring.

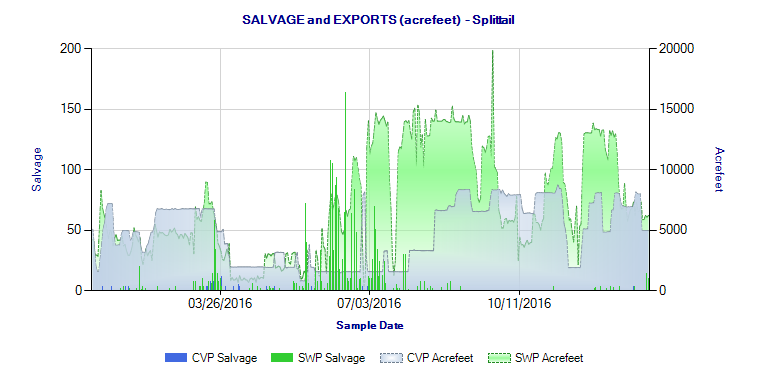

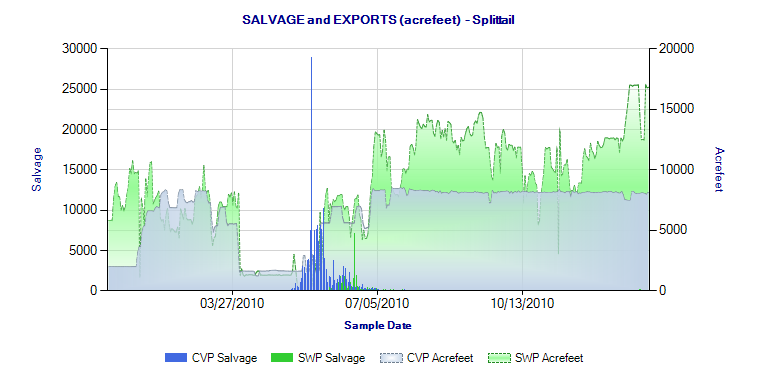

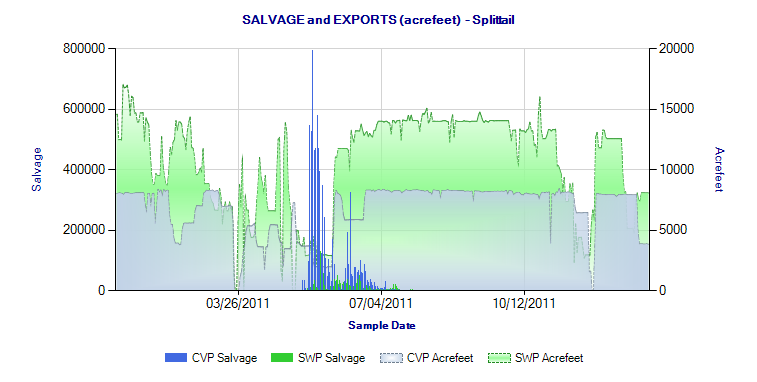

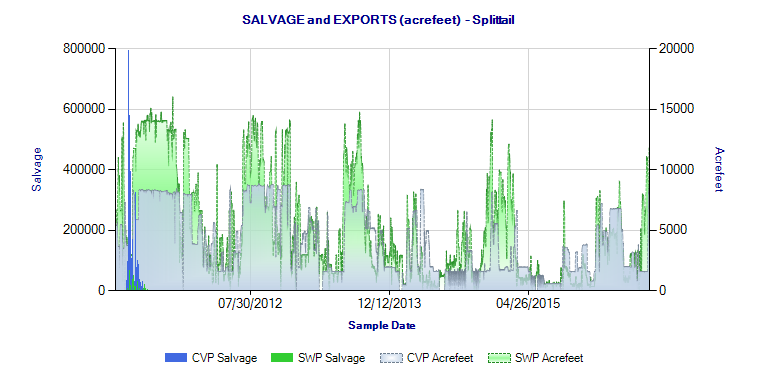

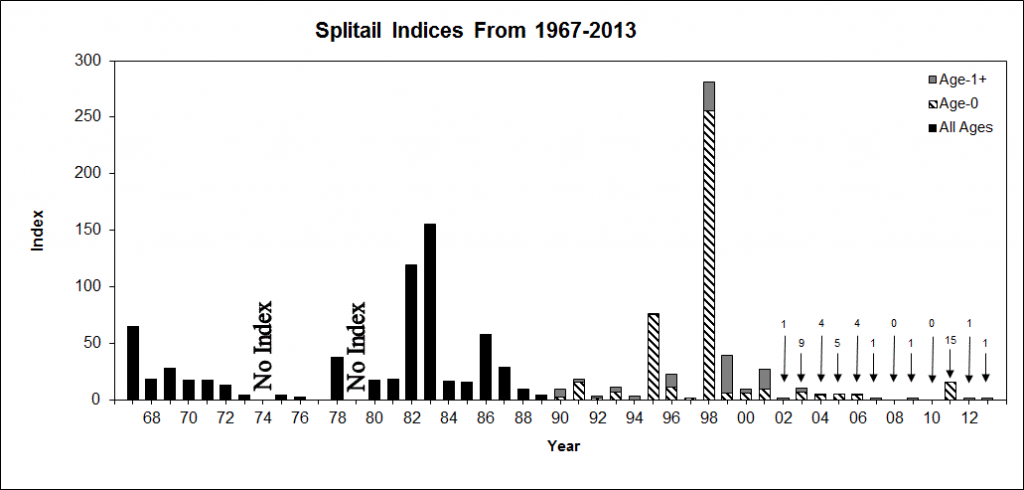

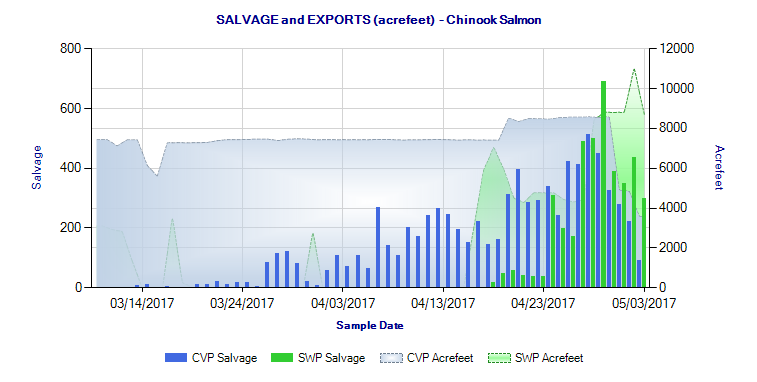

Total Delta exports reached 8,000 cfs in the first week in May, and salvage of salmon and splittail increased sharply (Figures 1 and 2). Normally, Delta standards limit export limits to1500 cfs in April-May in order to protect fish. However, higher exports are allowed when San Joaquin River inflows to the Delta are high. Even higher exports than the present 8,000 cfs are allowed, but the infrastructure cannot accommodate further exports in this wet year (demands are low and reservoirs south of the Delta are nearly full).

Figure 1. Salvage of Chinook salmon at south Delta pumping plants in spring 2017. Source: CDFW.

Figure 2. Salvage of splittail at south Delta pumping plants in spring 2017. Source: CDFW.

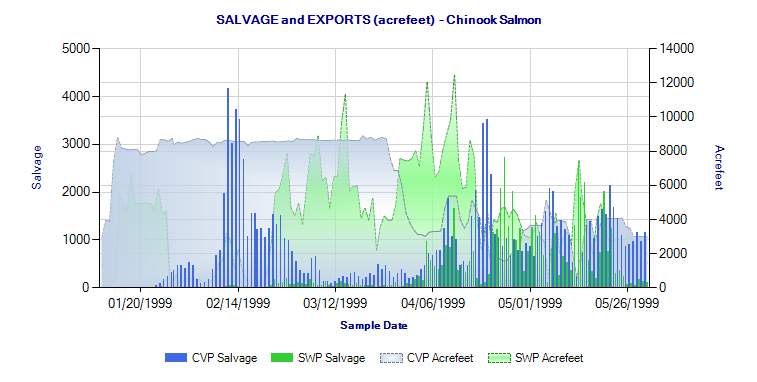

In past wet years, there were restrictions on south Delta exports in April and May to protect juvenile salmon, steelhead, splittail, and smelt that were rearing or passing through the Delta. These restrictions also protected adult and juvenile sturgeon. Figure 3 shows an example of Chinook salmon salvage in 1999. The initial peak in February 1999 salvage was salvage of fry (1-2 inches). The spring peaks were hatchery and river-reared smolts, primarily from San Joaquin River tributaries. Both exports and salvage dropped after April 15.

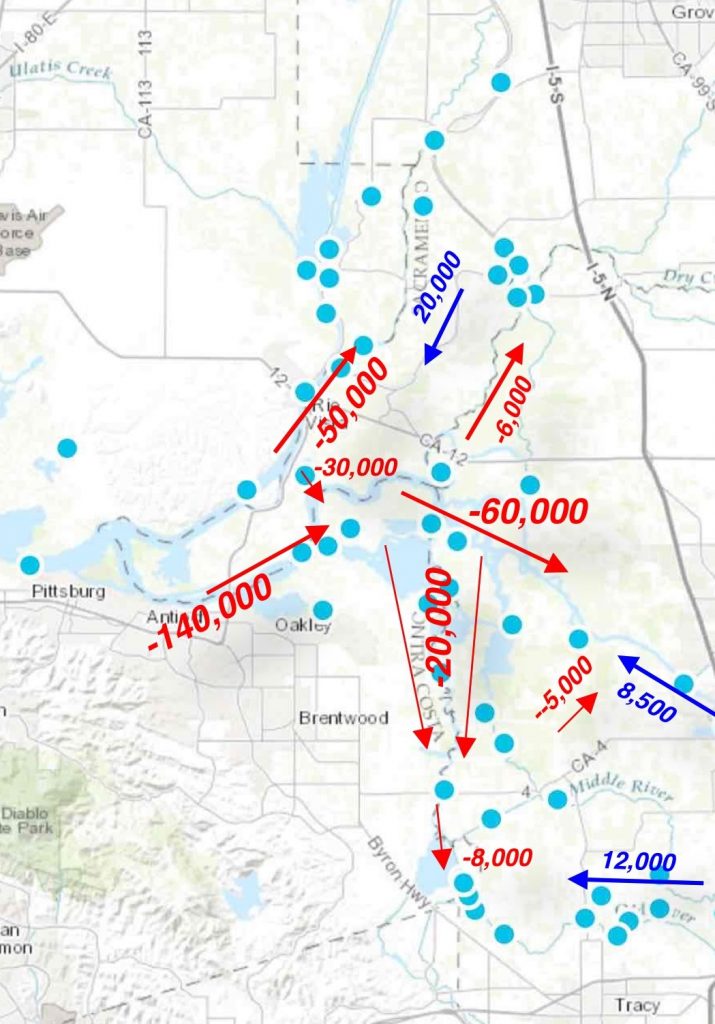

In 2017, with the diversion of over half the San Joaquin River’s flow into the south Delta through the Head of Old River and other channels (Figure 4), there is a definite risk that high export levels will draw young salmon and splittail from the San Joaquin into the south Delta. Once in the south Delta, they are subject to 8,000 cfs of diversions and a mix of tidal flows. The risk is even higher than it might seem, because the reported State Water Project diversion is a daily average. Water enters Clifton Court Forebay for only about one third of the hours in each day, during incoming tides. The reported 5000 cfs is actually more like 15,000 cfs operating for those eight hours, adding to the pull toward the pumps of the incoming tides.

Reported salvage is just the tip of the iceberg, because predators eat up to 90% of juvenile salmon that enter the Forebay before these juveniles ever reach the salvage facilities.

In conclusion, the State Water Board needs to change the Delta standard. It needs to limit spring exports even when San Joaquin flows are high. In 2006 (Figure 5), the now-defunct Vernalis Adaptive Management Program limited April through mid-May exports despite high San Joaquin flows. Salvage was markedly low during this period of limited exports.

If exports continue high through May and June in 2017, there will be detrimental effects on San Joaquin salmon, steelhead, and splittail, as well as on Delta smelt.

Figure 3. Salvage of Chinook salmon at south Delta pumping plants in winter-spring 1999. Note reduction in exports after mid-April. Source: CDFW.

Figure 4. High tide flows in the Delta at the beginning of May 2017. Blue represents positive downstream flows during high tides, where tides had minimal influence. Red denotes upstream tidal flow during incoming tides.

Figure 5. Salvage of Chinook salmon at south Delta pumping plants in winter-spring 2006. Note reduction in exports in early April. Winter-spring San Joaquin flows in 2006 were similar to those in 2017. Source: CDFW.