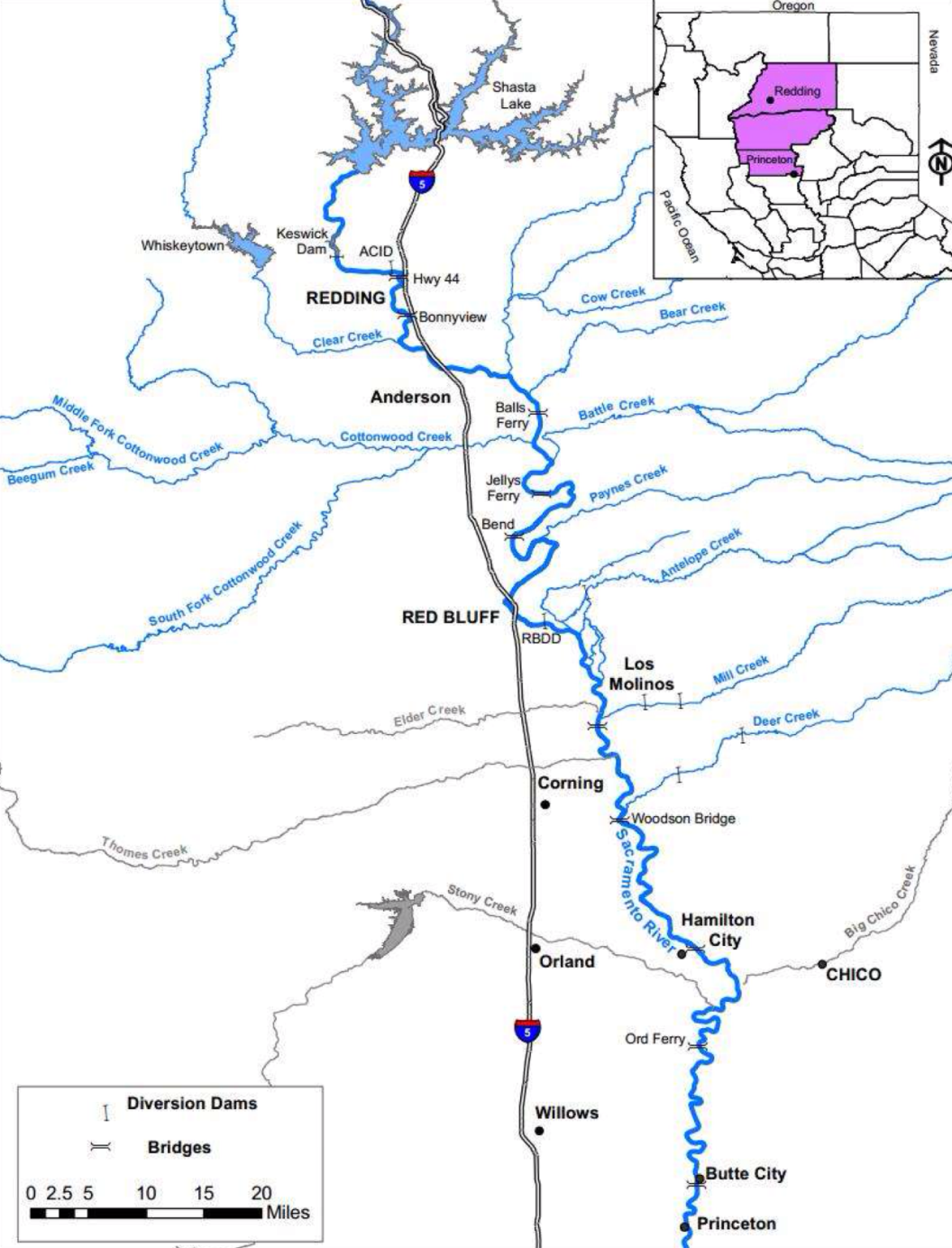

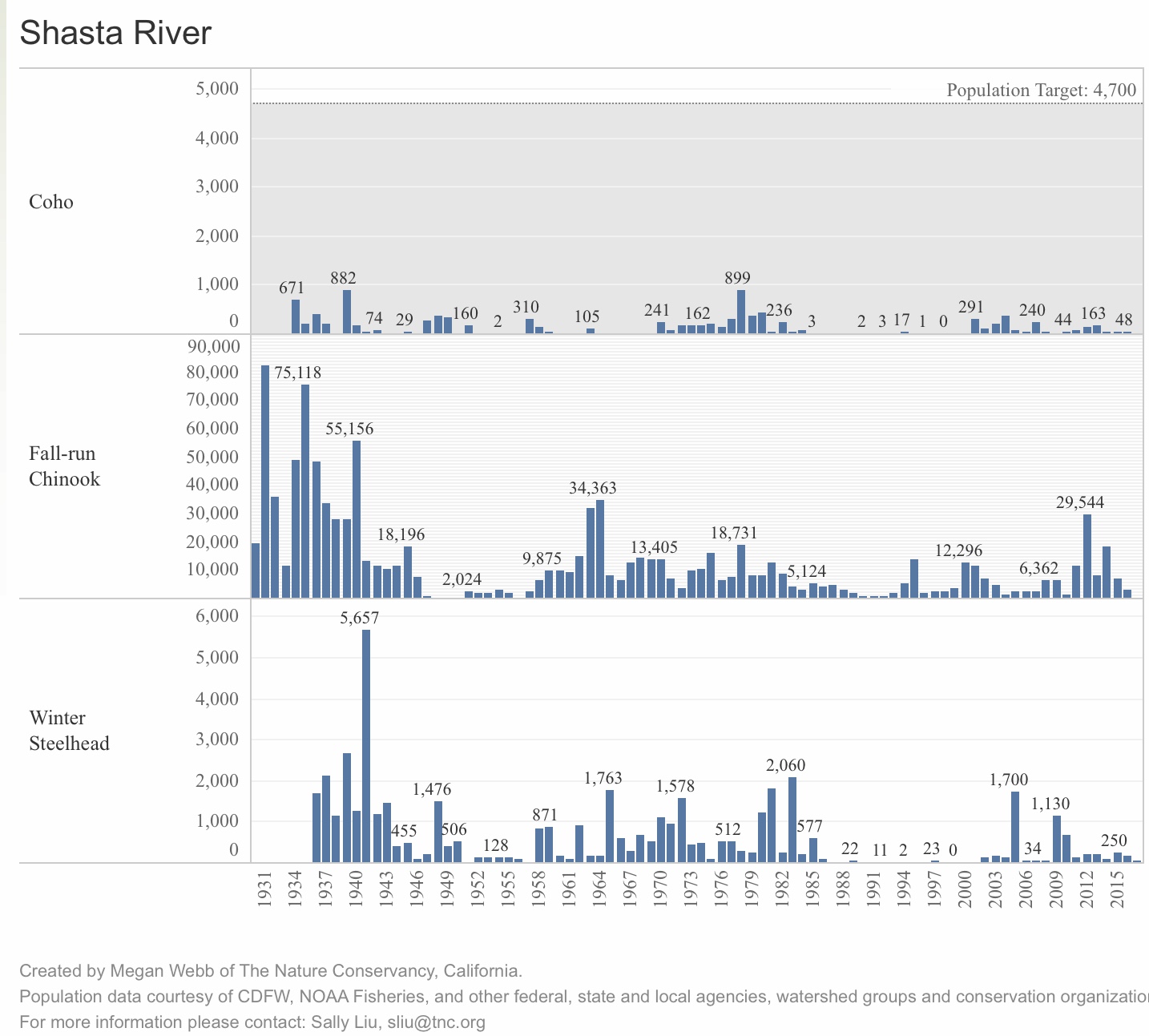

In a November 2019 post, I gave updates through 2018 on the status of fall-run salmon in the Scott and Shasta rivers, major tributaries of the Klamath. I described how continuing improvements in river management paid off for the Shasta River’s fall Chinook run. I also described how lack of protections in water management left the Scott run in poor condition.

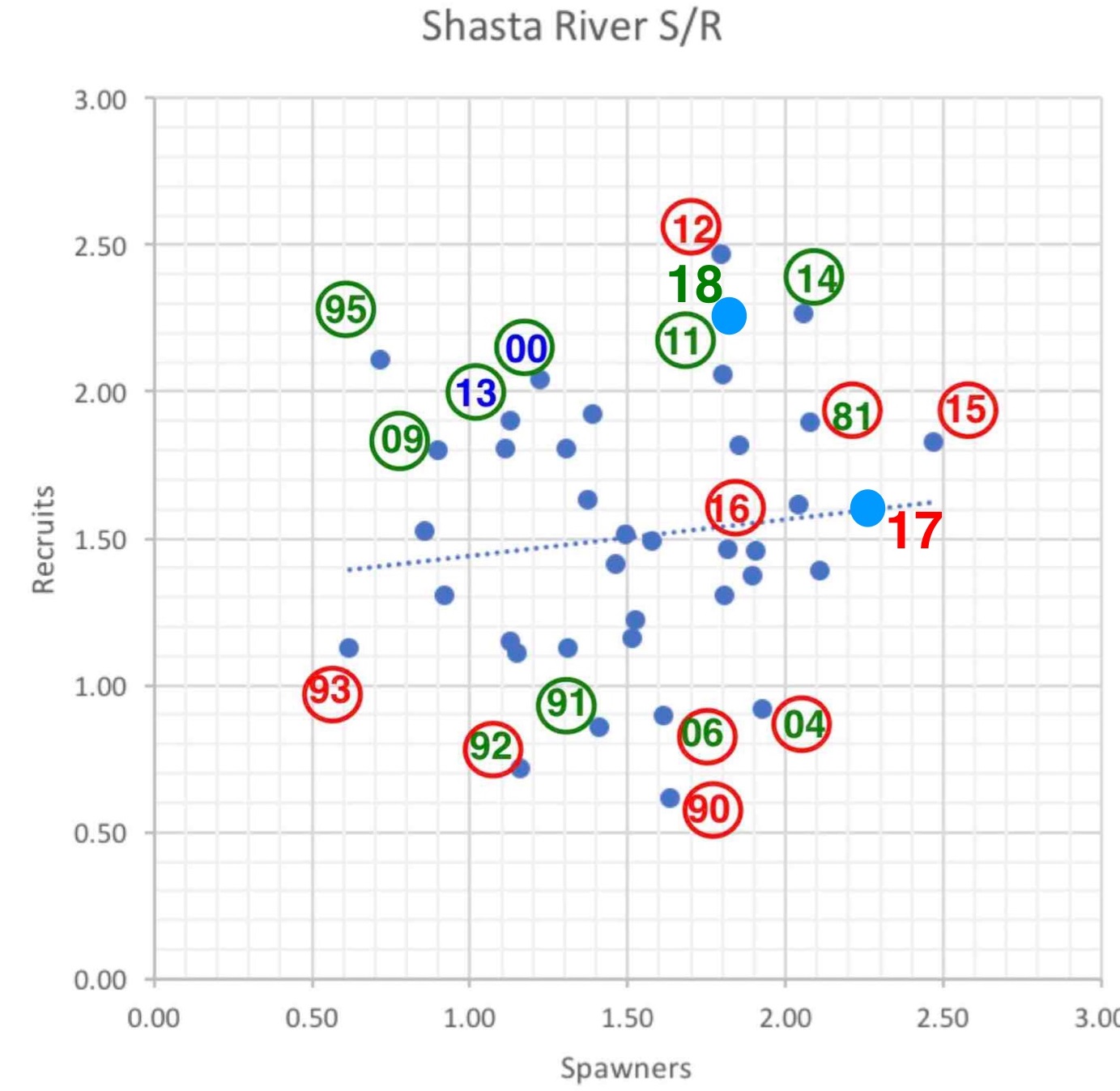

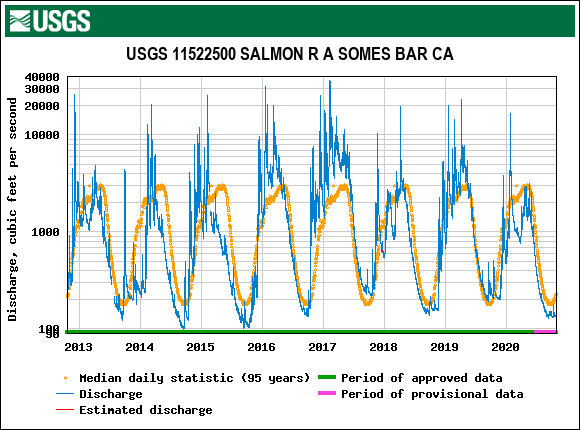

In this post, I update fall-run Chinook spawning escapement through 2019, with some insight into the 2020 runs. I also provide data on the runs in the Salmon River, the Scott and Shasta’s sister Klamath tributary. The 2019 salmon runs should have benefitted from water-abundant 2017, but may have been handicapped by poor numbers of returning spawners in 2016.

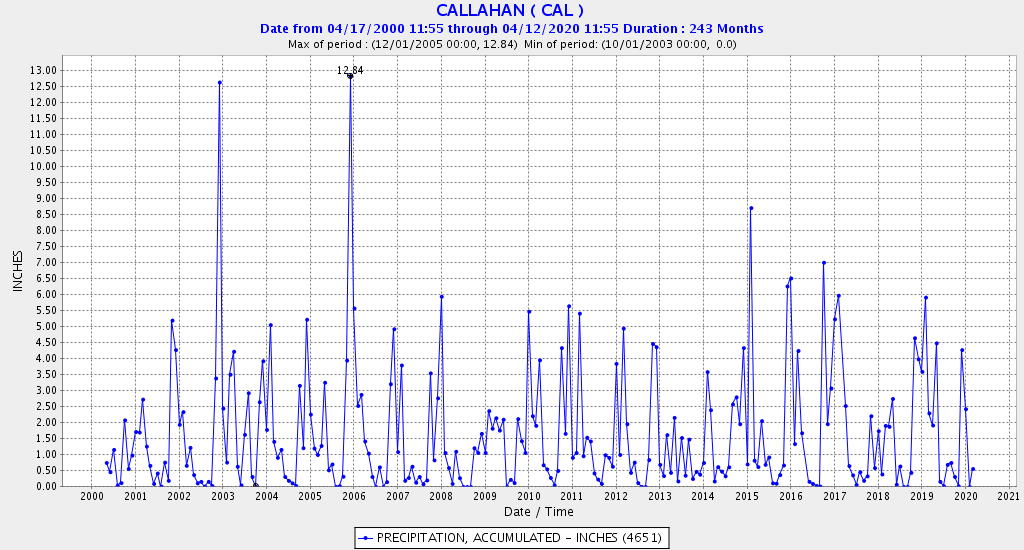

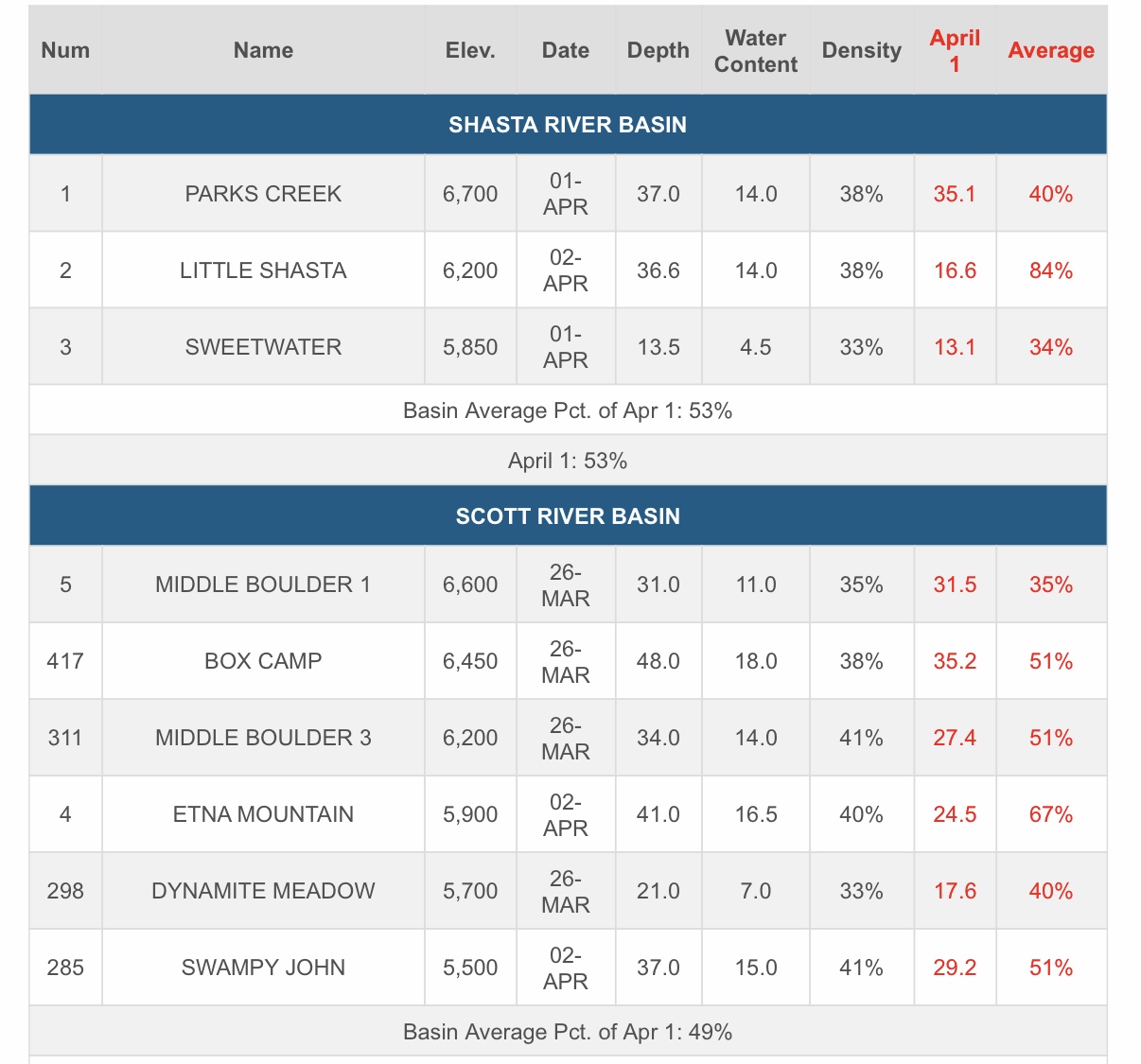

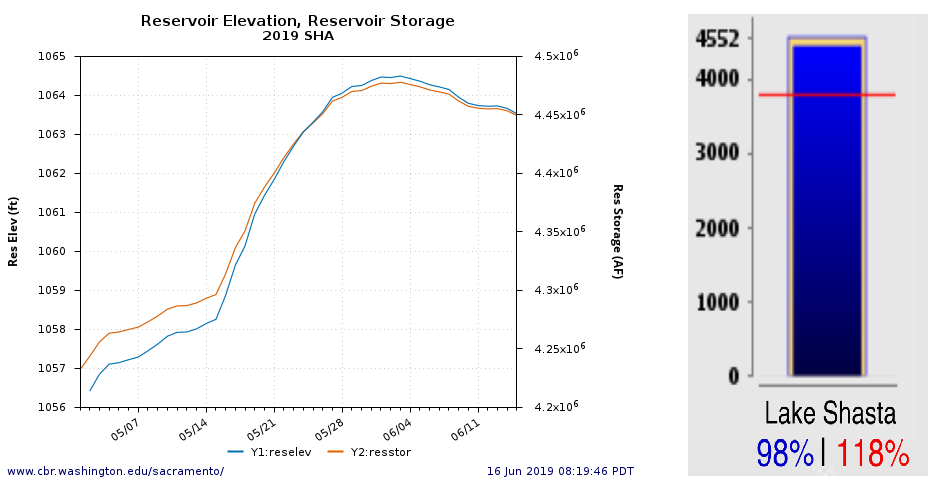

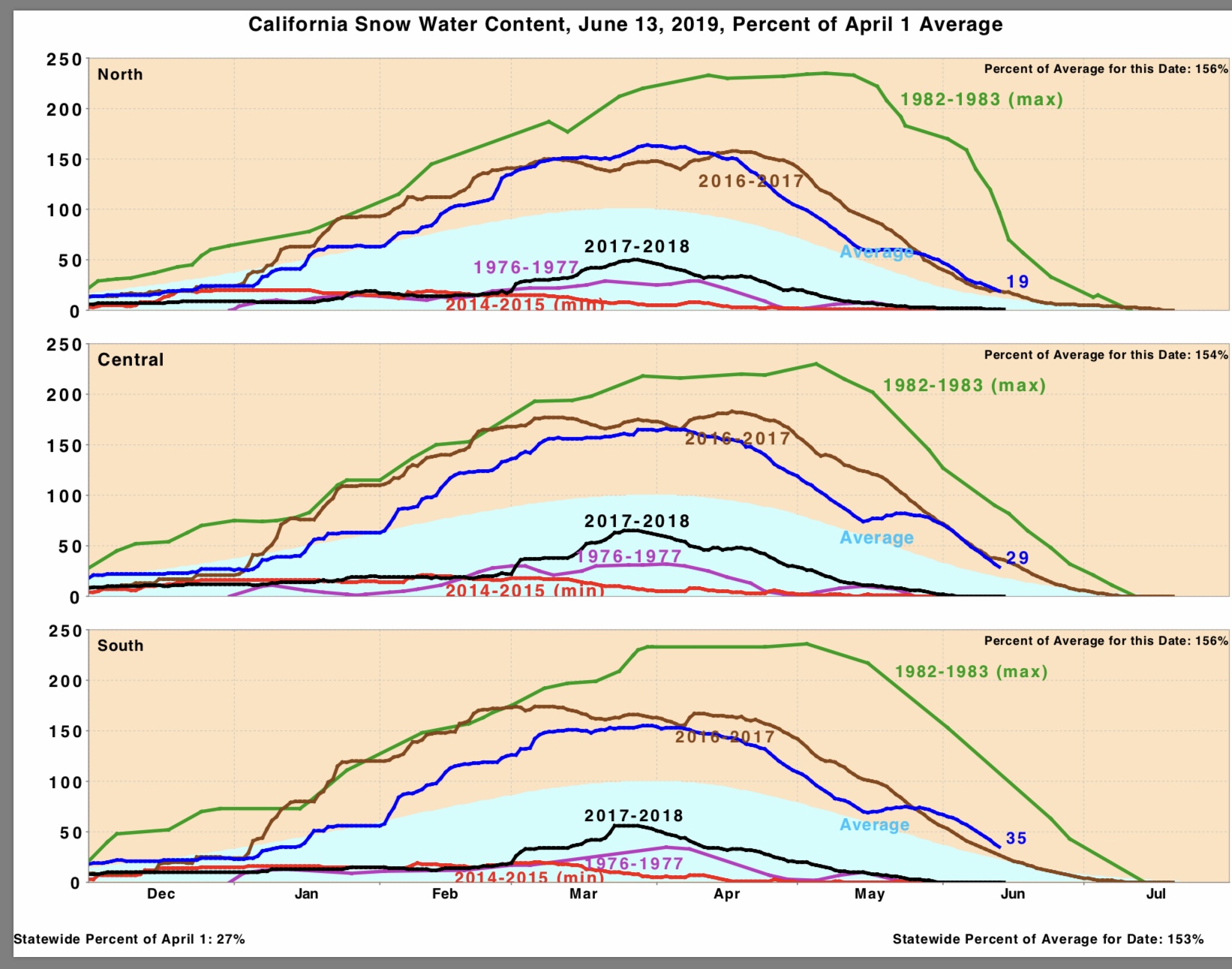

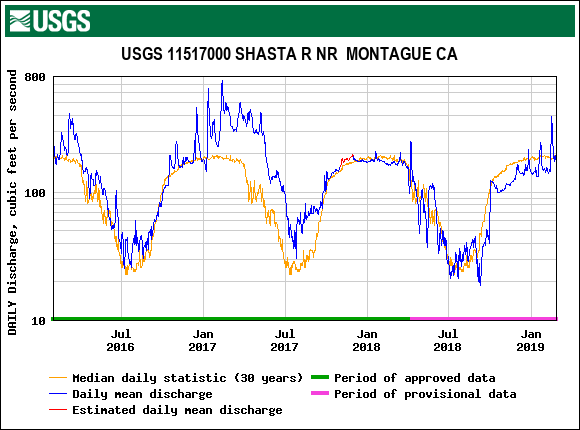

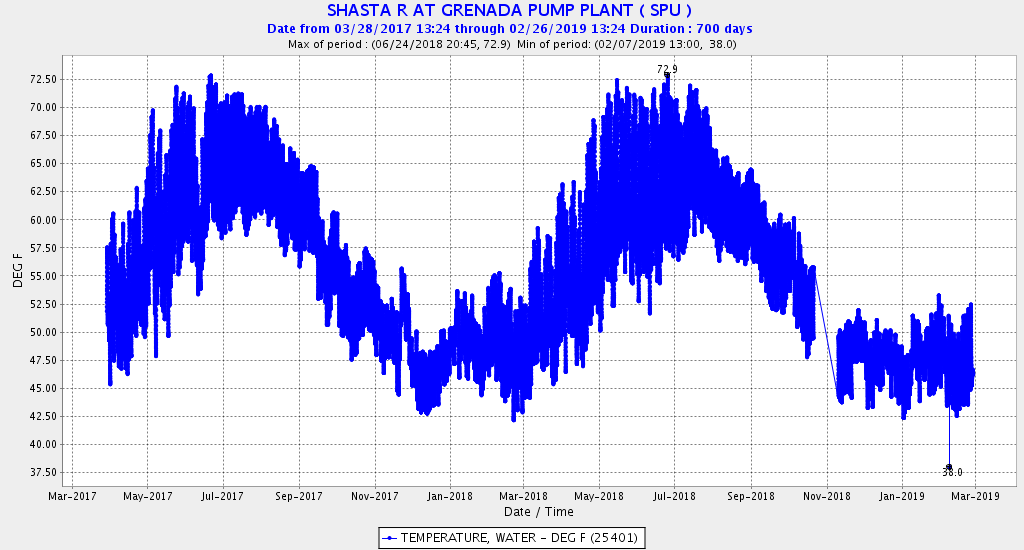

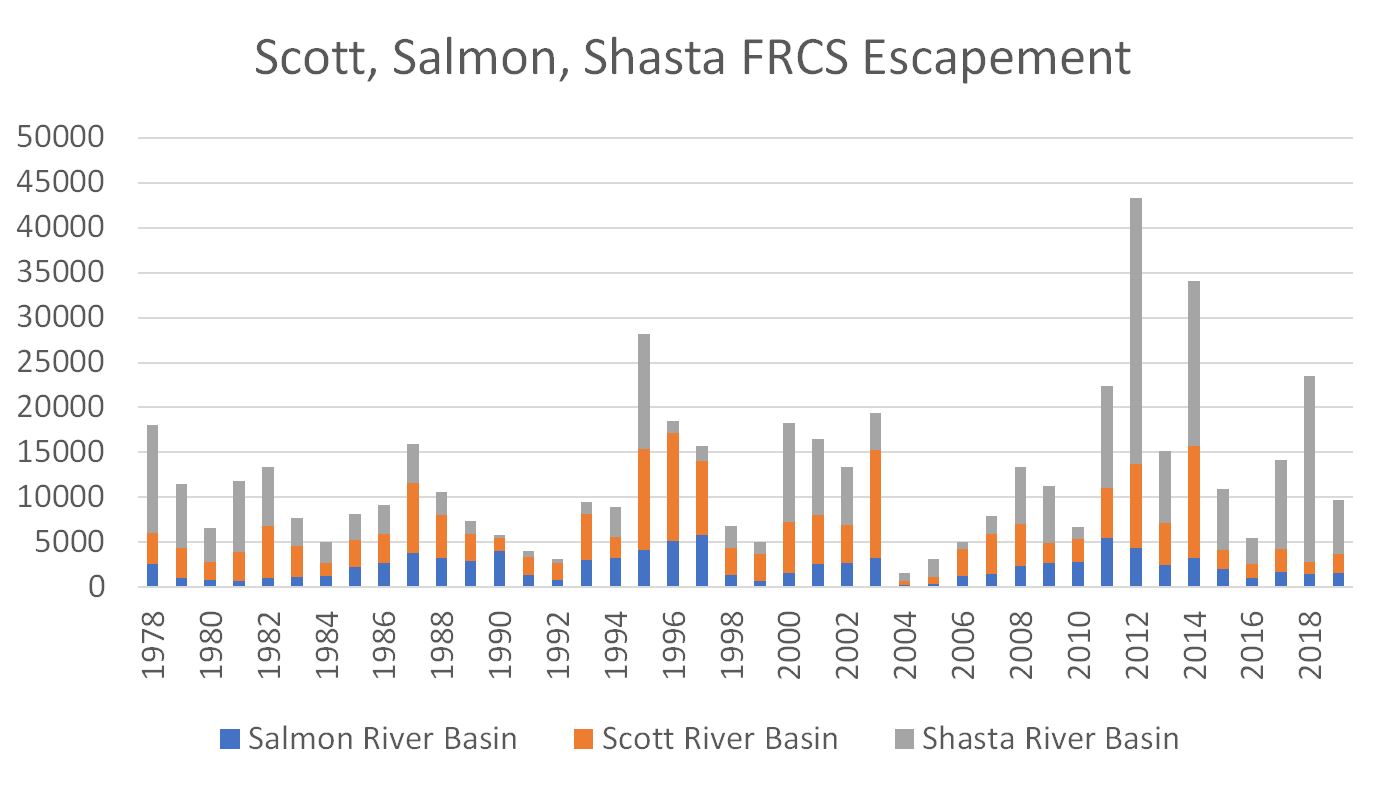

The runs of fall-run Chinook in all three of these major Klamath River tributaries improved in 2019 compared to the runs in 2016 that were severely affected by drought and fire.1 However, runs in all three rivers in 2019 fell short of the 2017 and 2018 runs (Figure 1). Good water conditions in all three rivers in 2017 (Figure 2)2 should have led to improvements in runs over 2017, which were a product of 2014-2015 drought and 2014 fires. They also should have been better than the runs in 2018, whose runs were spawned in drought year 2015 and reared in dry year 2016.

The fact that there was not greater improvement in the 2019 runs is likely the consequence of low numbers of spawners in the fall of 2016. The low number of spawners in 2016 resulted from the continuing effect of the devastating 2014 fires on the watersheds (especially the Salmon River), ongoing poor water management (especially in Scott and Shasta rivers), and poor water conditions in the dry falls of 2017 and 2018 (limiting 2019 the returns of 2-year-old “jacks and jills”).

The prognosis for 2020 is mixed. This results on the upside from improved numbers of spawners in 2017 and a wet water year in 2019. On the downside, the relatively poor water conditions in fall 2017 and the dry conditions in 2018 and 2020 are likely to depress the numbers of adults that return in 2020. Initial counts from Shasta and Scott rivers3 however indicate poor runs not unlike 2004 or 2016. Overall, the decline in spawners produced from strong runs (2014 and 2017) in the Klamath’s main wild salmon tributaries, as well as drought, fire, and continuing poor water management, do not bode well for the future of Klamath salmon.

Figure 1. Shasta, Scott, and Salmon River escapement of fall-run Chinook salmon 1978-2019. Source; CDFW data.

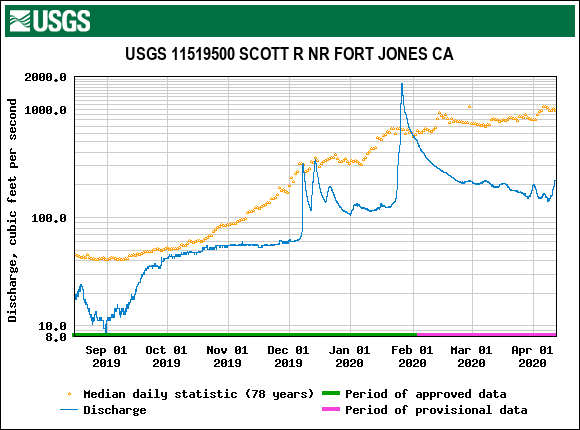

Figure 2. Salmon River streamflow 2013-2020 with long-term average.

- https://www.fs.usda.gov/detailfull/klamath/home/?cid=stelprd3829437 ↩

- See prior post for Shasta and Scott streamflows ↩

- http://svrcd.org/wordpress/ ↩