In an April 13 post I discussed what happened in 2014 that led to the catastrophic loss of much of the Winter Run Chinook Salmon production in the Sacramento River when Shasta Reservoir’s cold-water pool was depleted by the end of August. With a better temperature model, more knowledge of how to manage Shasta’s cold-water pool, and more volume in the cold-water pool this year, the agencies believe they can make it through the summer of 2015 while supplying the same amount of water to the Sacramento River Settlement Contractors (SRSC) with the same end of September storage as last year.

On April 20, 2015, the Bureau of Reclamation released a “Framework” for managing Shasta storage and the Sacramento River in 2015. The problem with the Framework is that there are no details as to how the state goals of protecting Winter Run while delivering the same amount of water to SRSC in 2015 as last year will be accomplished.

“Agreement on Sacramento River and SRSC operations is the cornerstone to the overall operations of our water management system, and is a key piece needed before other decisions about volume and timing of transfers to junior water rights holders can be negotiated…. This type of creative, cooperative approach among project operators, regulators, and water users is fundamental to getting the most out of our limited water resources…. We must continue close coordination as we implement the plan, reacting to real-time conditions and balancing the inevitable tradeoffs.” The problem with this statement is that it was also true for last year. Despite these same efforts, over 95% of the endangered Winter Run salmon production below Shasta was lost last summer to failed efforts.

“Last year, endangered winter-run Chinook salmon redds in the upper Sacramento River were severely impacted by the lack of cool water,” said Maria Rea, Assistant Regional Administrator for NOAA Fisheries Central Valley Office. “This year we will continue to monitor the temperatures and operations of the Sacramento River throughout the summer.” Part of the cause of widespread mortality of the 2014 Sacramento River cohort of Winter Run salmon was lack of cold water, but only part. In addition, salmon redds were physically dewatered and eggs and fry were stranded. This could occur again this summer. When monitoring indicated there was a problem last summer, it was too late to take action.

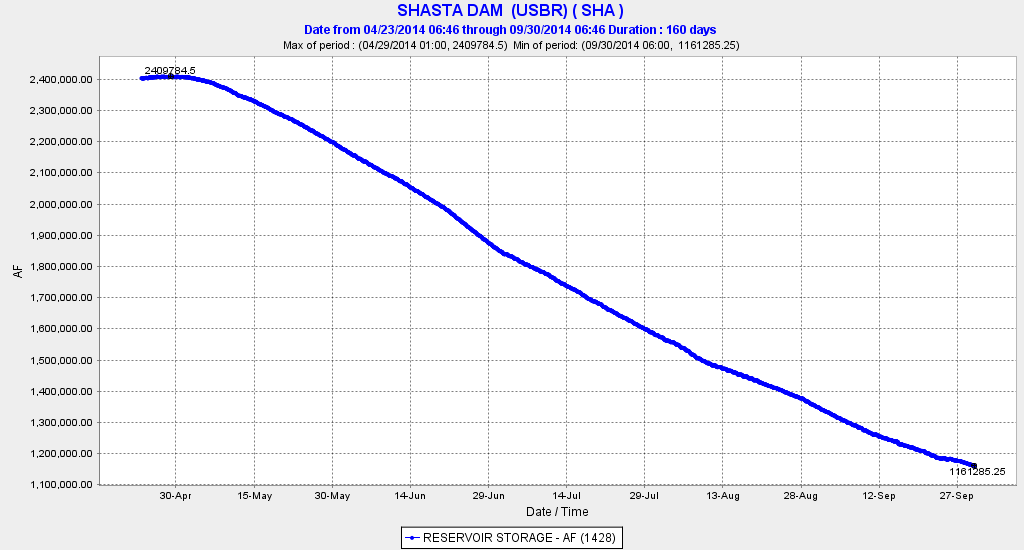

“A major component of the overall framework is the temperature management plan for the Sacramento River. With the proposed temperature management plan and anticipated CVP operations assuming conservative inflow estimates, storage in Shasta Lake is projected to be approximately 1.1 million acre-feet at the end of September 2015. Water storage and releases from Shasta Lake will be managed carefully to assure the availability of water for multiple beneficial purposes during this fourth year of drought.” This is the same end-of-summer storage level as last year. Water storage, releases, and water temperatures were managed last summer. What specifically will change to ensure that last year’s problem will not reoccur? The Bureau’s website offers no clue.

“Reclamation will submit the temperature management plan to the State Water Resources Control Board next week as required by the recent Temporary Urgency Change Order.” The plan will be based on this year’s conditions and a new temperature model. What assurances do we have that this year’s plan and model will work better than last year’s?

In order to save salmon in 2015, the Bureau Reclamation proposes: “The following actions are designed to help increase the available cold-water resources, improve habitat for Chinook Salmon, and inform real-time adjustments to the temperature management actions, all of which serve to improve the overall effectiveness of the temperature management plan:

- “The State Water Resources Control Board approved (in part) Reclamation’s April-September Temporary Urgency Change Petition on April 6, 2015, which will maintain minimum flows for fish downstream in the Delta. This will help Reclamation preserve as much cold water as possible in Lake Shasta for its operations and temperature management throughout the spring and summer as well as for water supply purposes.” (Note: minimum required lower Sacramento River flows are adequate to maintain minimum Delta inflow and outflow requirements. Shasta releases are necessary only for required in-river flows and water temperatures and to meet SRSC irrigation deliveries.)

- “Biologists from the State and Federal fish agencies will be working in the Sacramento River this summer collecting data to help inform Reclamation operations and temperature management decisions in real time. This work will also provide additional data on salmon spawning and rearing that will be useful in future operations during both dry and wet years.” (Note: the agencies have been collecting data for many years, including last year, when Winter Run mortality was extremely high.)

- “For the remainder of 2015, the SRSCs, working with the state and federal fishery agencies and conservation partners, will aggressively implement projects included in the Sacramento Valley salmon recovery program. This includes actions to improve spawning in the upper Sacramento River, protect (against) stranding and increase the survival of salmon smolts.” (Note: How will the contractors contribute to these actions?)

- “A significant portion of the anticipated water transfers from the SRSC’s will be released in the late summer and fall on a schedule that will provide beneficial habitat conditions for spawning fall-run salmon.” (Note: this was done last year. Summer transfers would continue to deplete the cold-water pool and degrade the critical habitat of listed smelt in the Delta by increasing Delta exports. Fall transfers through the Delta are also detrimental and not normally allowed.)

- “The federal and state agencies and SRSC’s will have regular meetings to coordinate these actions and will work closely together throughout the year to assure the effective implementation of this plan. We all agree that we stand a better chance of managing limited water supplies with continued communication and cooperation.” (Note: last year, there was ample communication, yet most of the fish perished. What will cause the agencies to make better decisions this year?)

Some key facts:

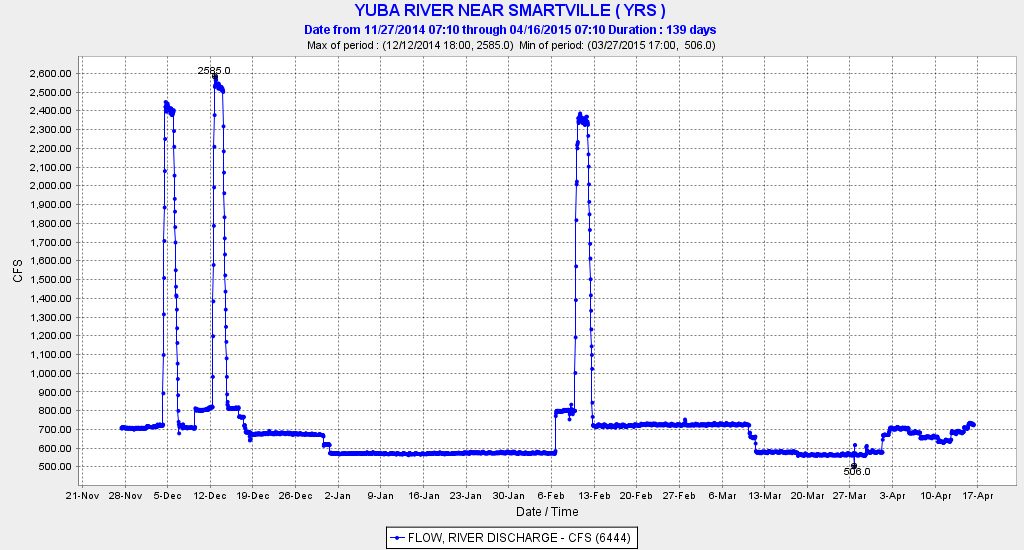

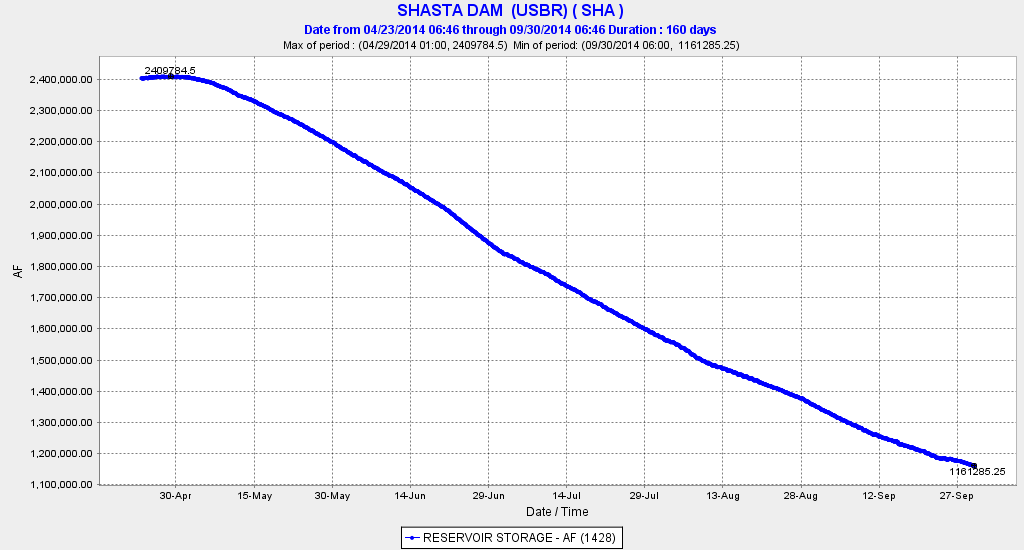

- Last year Shasta started with 2.4 million acre-ft and ended up with 1.1 million acre-ft (Figure 1). This year the plan is to start with 2.7 million acre-ft and end with 1.1 million acre-ft. (Note that the benefits of this year’s higher spring storage level is offset by a reduced snowpack)

- The Bureau states that the Shasta cold-water pool has 0.7 million acre-ft more at the beginning of this year than last year.

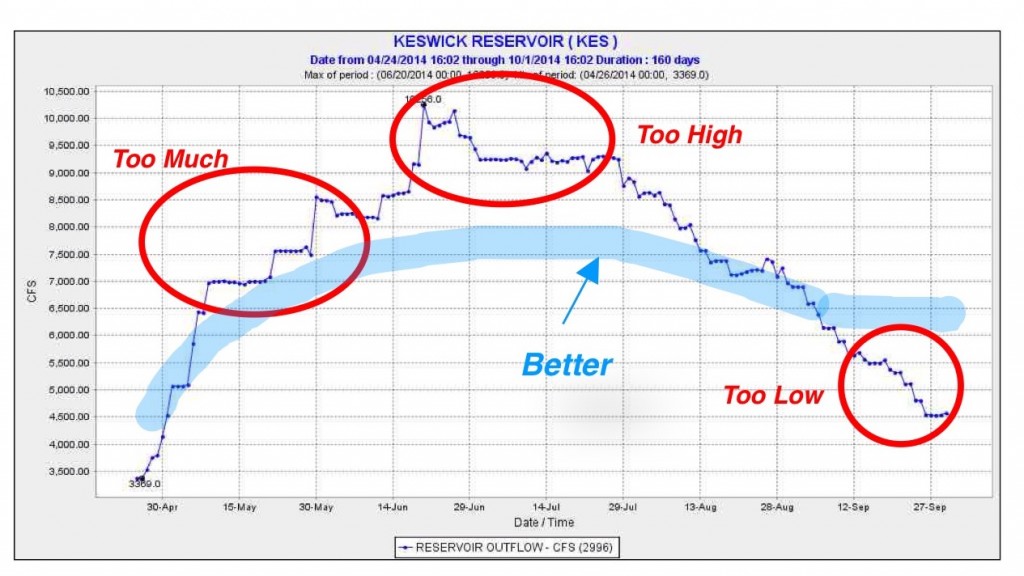

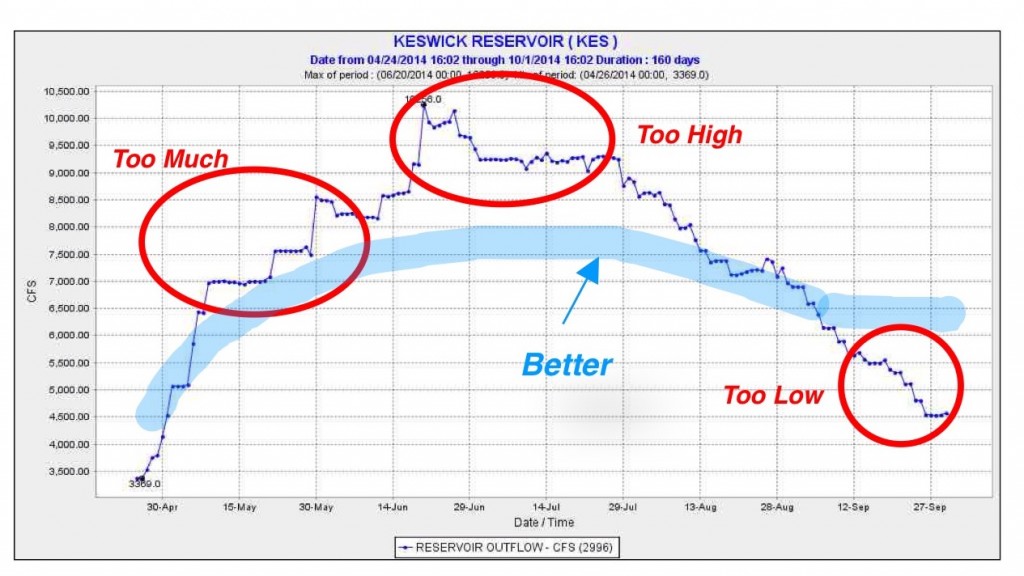

- Last year the Bureau ran out of cold water, resulting in lethal water temperatures and low dissolved oxygen for salmon eggs and fry in spawning reach near Redding, and then dropped flows too low, resulting in dewatered redds.

- Reservoir releases were too high in spring and too low in late summer and fall for good salmon survival (Figure 2).

In conclusion:

- There are no plans to save Shasta storage for carryover for next year despite the 300,000 acre-ft additional storage this year.

- There is no explanation for how summer deliveries in 2015 that are functionally equivalent to summer deliveries in 2014 will maintain the cold-water pool in Lake Shasta this year when they caused last year’s disaster.

- There are no assurances that late summer and early fall flows will be high enough to avoid dewatering salmon redds near Redding.

- There are no assurances that addition summer and fall reservoir releases will not be needed to sustain the Bay-Delta ecosystem.

Figure 1. Shasta Reservoir storage 2014. Source: CDEC.

Figure 2. Shasta Reservoir releases 2014. Source: CDEC.

The small numbers of Steelhead I have caught or seen caught, or observed while snorkeling, are most often hatchery fish, likely strays originating from the Feather River Hatchery. In fact, a small percentage of the resident trout above and below Daguerre are hatchery steelhead that did not migrate to the ocean (photo at right). Hatchery smolts released in the lower Feather River near the mouth of the Yuba often move up the Yuba.

The small numbers of Steelhead I have caught or seen caught, or observed while snorkeling, are most often hatchery fish, likely strays originating from the Feather River Hatchery. In fact, a small percentage of the resident trout above and below Daguerre are hatchery steelhead that did not migrate to the ocean (photo at right). Hatchery smolts released in the lower Feather River near the mouth of the Yuba often move up the Yuba.