In this blog I often recommend barging hatchery and even wild salmon from spawning rivers to the Bay up to 200 miles or more over conventional trucking or direct releases from hatcheries. The theory is that continuous recirculation of water in the barge (or boat) holding tank helps the young salmon remember from where they came and imprint the route back to their home river or hatchery. Trucking directly to the Bay is believed to cause straying to non-natal rivers, resulting unnatural mixing of stocks, hatchery fish straying into wild fish spawning rivers, and less salmon returning to their home hatcheries where their eggs may be needed to meet quotas. It is well documented that trucking and pen acclimation significantly increases the contribution of hatchery smolts to the ocean fishery up to two or three fold or more. Concern over straying has kept the practice to a minimum.

Well it turns out from studies conducted with tagged hatchery salmon beginning with releases in 2008 that trucking, at least of American and Feather hatchery smolts, does not lead to significant amounts of straying. Also, barging does not significantly reduce the already low straying rate. So trucking to Bay net pens for acclimation remains the chosen strategy for the two largest State hatcheries, and probably the other two on the Mokelumne and Merced rivers.

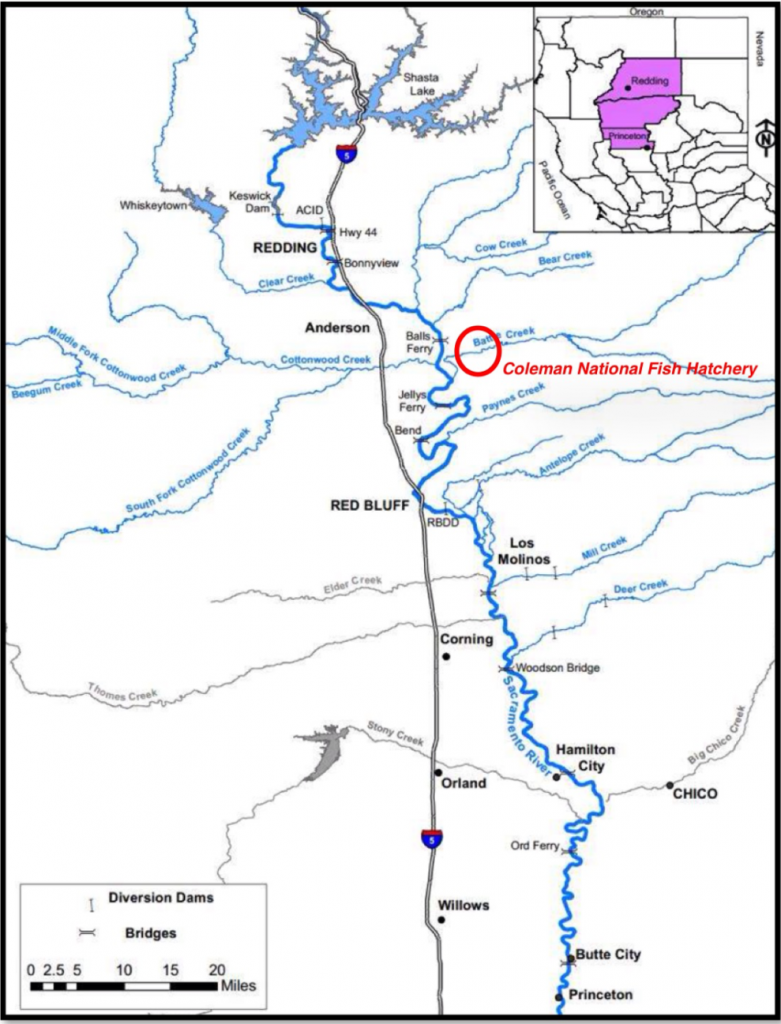

The jury is still out on the Coleman and Livingston Stone federal hatcheries near Redding. Straying rates are higher and the benefits of trucking over 200 miles seem questionable. One concern I have is the high straying rate encountered for Coleman (Battle Creek) fish includes fish that move past Battle Creek further up in the Sacramento River and its upper tributaries. Most of the spawning fish in these areas come from Coleman and Livingston Stone national fish hatcheries. Because Coleman was built to mitigate for the loss of fish to those areas, I question their inclusion in the straying estimates. The USFWS, which manages the two hatcheries, continues to be reluctant to truck and barge fish.

Though barging may not be needed for the Feather and American River hatcheries, it still holds potential for improving survival and reducing straying overall. So far, there is no evidence that barging improves survival over trucking to Bay net pens. I reviewed subsequent tag returns for a barge release group in early May 2012 with returns from two net pen groups released at the same time in the Bay. I found the subsequent return percentage of the barge group to be in between the two trucked pen release groups. In the notes of the barge release, high predation by birds was noted. In the photo of a barge release below many birds can be seen. I wonder if the barge release would also benefit from the same pen acclimation that is employed after trucking, which significantly improves trucked fish release survival and subsequent contribution to the fishery. (Note: I have been present at numerous truck releases to the Bay and have observed obvious extreme predation on the disoriented and confused hatchery fish, often released into warmer, saltier water than was present at the hatchery by a horde of well-trained and waiting birds and predatory fish. Release to net pens at variable locations for acclimation and tow to open waters for underwater release seemed to greatly reduce predation, which proved true in subsequent tag returns.)

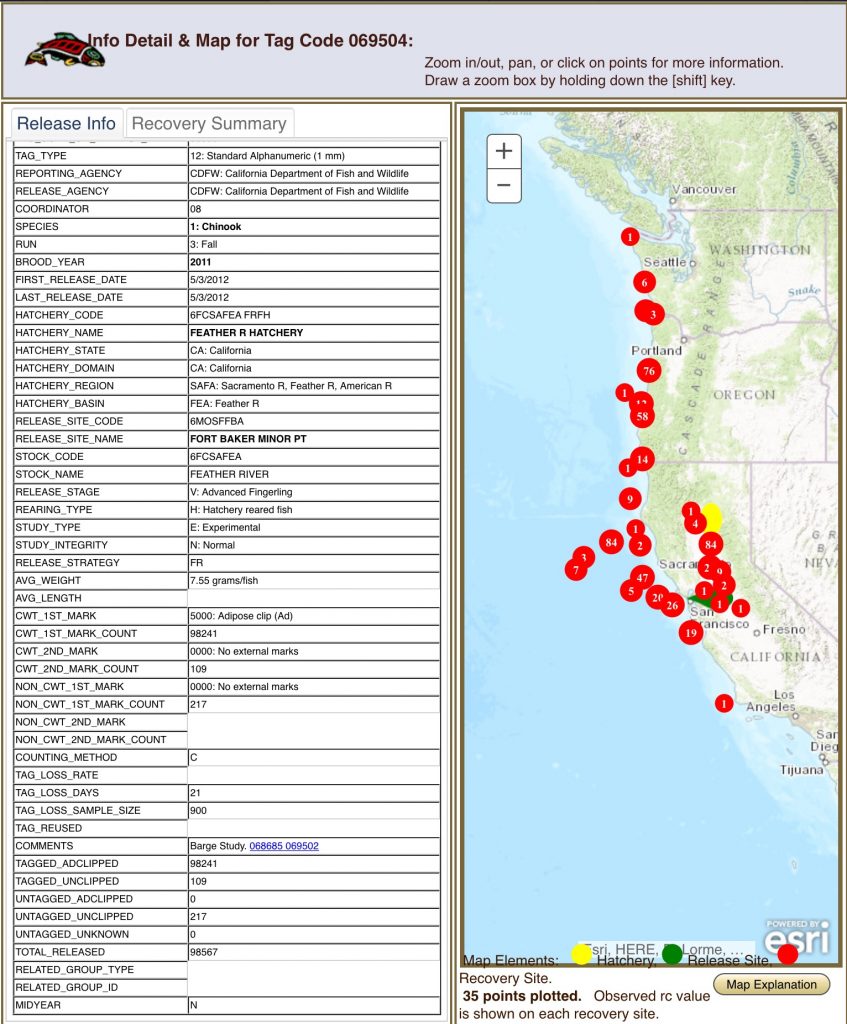

A closer look at the tag-release-recovery data and further experimentation would better answer the questions, concerns, and hypotheses. There were nine barged groups released into the Bay from 2012-2014. With some tags still out or not processed (tags are in noses of adult fish returns 2-4 years after release), information continues to come in. The nearly million or so coded-wire-tags released from the nine barge groups swam with approximately 30 million other tagged fish from the six Central Valley hatcheries. Furthermore, records are meticulously kept with other tagged groups from Washington and Oregon, as well as from other California watersheds (e.g., Klamath), by the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission. An example of the type of information available is shown in the map-chart below for just the one barge release group from 2012. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has its own team and program to keep track of California immense database on releases and recoveries. The Department’s report from November 2015 provides an excellent review of the whole process and results to date.