I have fished and studied the Lower Yuba River above Marysville for nearly 20 years. This tailwater fishery below Englebright Dam is one of California’s best wild trout fisheries, rivaling that of the Keswick tailwater on the lower Sacramento River below Redding. Both are nearly as good and as popular as the Deschutes River in north-central Oregon, a tributary of the Columbia River. All three rivers are national treasures above and below their dams. But it is the tailwater fisheries that provide for healthy, fast-growing populations of wild resident trout that thrive on nearly perfect year-round conditions for growth: controlled flows, cool water temperatures, and abundant food. Each river has abundant salmon eggs, fry, and flesh that supplement the highly productive waters from their reservoirs.

The Yuba tailwater Rainbow Trout fishery also benefits from Daguerre Dam, a sediment retention and irrigation diversion dam located about halfway up the 20-miles of lower river from Marysville. This small dam blocks runs of migratory predators and competitors from entering the upper tailwater reach. Striped Bass, American Shad, and Sacramento Pikeminnow are very abundant below Daguerre, especially in spring. Adult Chinook Salmon, Steelhead, and Rainbow Trout readily pass upstream through Daguerre’s two fish ladders, while the others do not. The resident trout thrive in the predator-free reach above Daguerre.

Wild Steelhead, the anadromous form of Rainbow Trout, do not thrive in the Lower Yuba River (nor lower Sacramento), however. Yuba River Steelhead are in the Central Valley Steelhead grouping listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act. The reason is simply that they must pass downstream to the ocean as young and back as adults. The odds of making the journeys are slim, especially for the young. Research has shown that the numbers of young trout drop precipitously below Daguerre, ostensibly from predation1. Steelhead young are adapted to migrating to the ocean during the high winter-spring rain-snowmelt season. With the large Bullards Bar Reservoir holding back the much of the seasonal high flows for summer irrigation, especially in dry years, Steelhead young have a tough time surviving the journey to the ocean.

The small numbers of Steelhead I have caught or seen caught, or observed while snorkeling, are most often hatchery fish, likely strays originating from the Feather River Hatchery. In fact, a small percentage of the resident trout above and below Daguerre are hatchery steelhead that did not migrate to the ocean (photo at right). Hatchery smolts released in the lower Feather River near the mouth of the Yuba often move up the Yuba.

The small numbers of Steelhead I have caught or seen caught, or observed while snorkeling, are most often hatchery fish, likely strays originating from the Feather River Hatchery. In fact, a small percentage of the resident trout above and below Daguerre are hatchery steelhead that did not migrate to the ocean (photo at right). Hatchery smolts released in the lower Feather River near the mouth of the Yuba often move up the Yuba.

So how can we improve the Steelhead population and protect the wild trout fishery in the lower Yuba River?

- There need to be habitat improvements: instream wood, riparian vegetation, side channels, and spawning gravel are generally or locally lacking in the lower Yuba, especially below Englebright and Daguerre dams.

- Hatchery Steelhead smolts should not be released in the lower Feather River; instead they should be trucked to Sacramento River, then barged to the upper Bay.

- Wild fry, fingerling, and smolt Steelhead/Rainbow Trout can be captured as they pass downstream at Daguerre Dam, and then trucked/barged to upper Bay.

- Predators should be removed from lower Yuba below Daguerre Dam by operating weir traps during dry springs. Striped Bass can be relocated to San Francisco Bay.

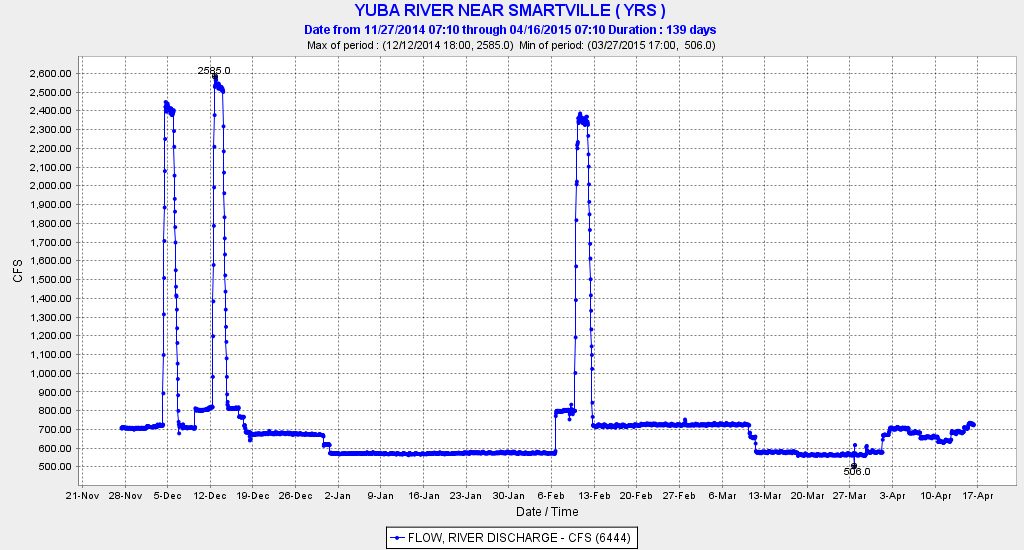

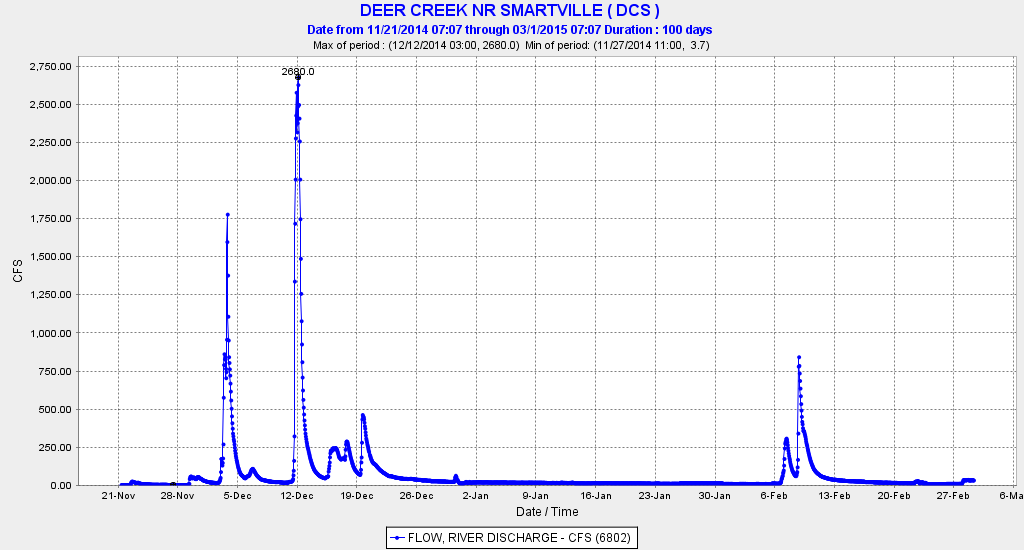

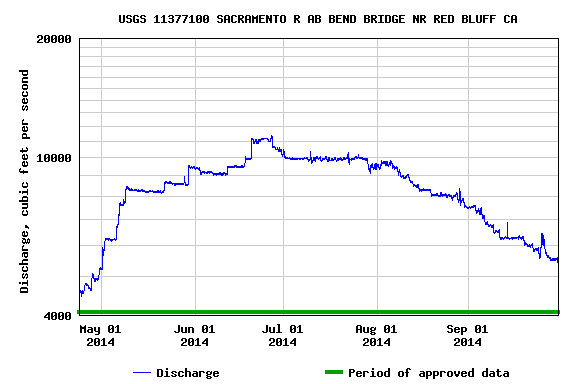

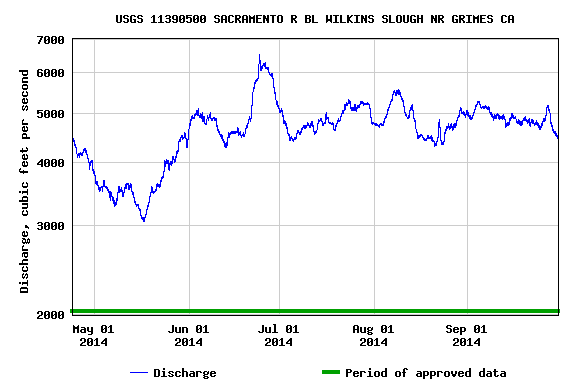

- Project operations can reduce stranding. Steelhead (and salmon) fry are stranded in large numbers on floodplains and river bars after infrequent winter-spring storms (see charts below). Upstream dam releases should increase before and after storms to better ramp flows to reduce stranding and other detrimental effects of sudden high flows.

- Anglers should be encouraged to keep hatchery trout and steelhead (adipose fin-clipped fish) caught on the lower Yuba.

- Wild adult Steelhead should be used in a conservation hatchery component of the Feather River Hatchery to help restore wild Yuba/Feather Steelhead. Wild Steelhead can also be restored to river above Englebright and Bullards Bar dams in a trap-and-haul program as prescribed in federal Recovery Plan for Central Valley Steelhead.