In the coming months and years, regulatory processes involving water rights, water quality, and endangered species will determine the future of Central Valley fishes.

To protect and enhance these fish populations, these processes will need to address four fundamental needs:

- River Flows

- River Water Temperatures

- Delta Outflow, Salinity, and Water Temperature

- Valley Flood Bypasses

In this post, I summarize a portion of the issues relating to River Flows: spring flows. Previous posts covered fall and winter flows.

River Flows – Spring

River flows in spring drive many natural ecological processes in the Central Valley related to Sierra snowmelt. Winter-run and spring-run salmon, steelhead, Pacific lamprey, and white and green sturgeon ascend the rivers from the ocean during the spring snowmelt season. Spring-run salmon arre able to migrate upstream in the high water to hold until late summer spawning. Winter-run salmon and sturgeon spawn in the Sacramento River below Shasta that same spring. Pacific lamprey spawn in streams throughout the Valley in spring. Juveniles, and remnant yearlings of all these species spawned in the previous year, head to the ocean in the high flows. In the Valley, the spring snowmelt and rains swell the rivers for the annual runs of Delta smelt, splittail, American shad, Sacramento suckers, and striped bass. In the Bay-Delta, spring flows spur annual productivity that sustains juvenile longfin smelt, Delta smelt, fall-run salmon, green and white sturgeon, striped bass, American shad, and splittail, as well as many resident and estuarine fishes and their food supply.

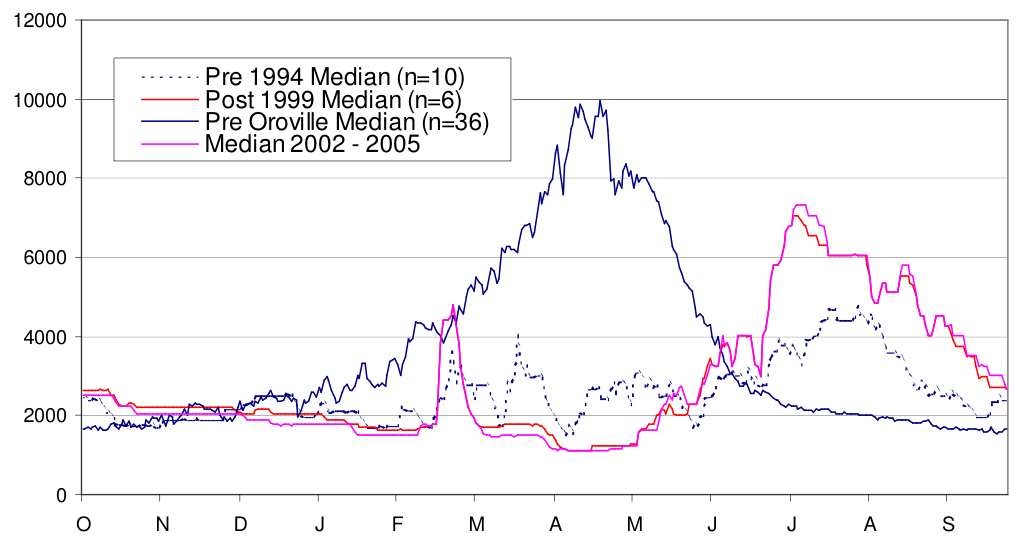

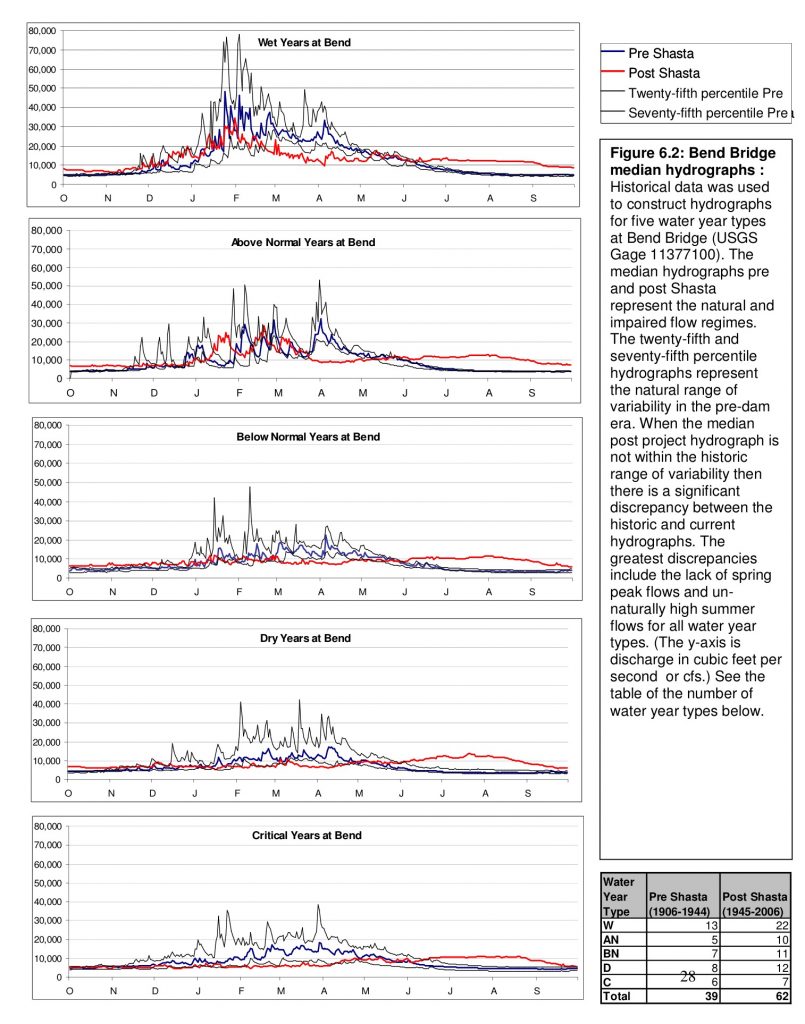

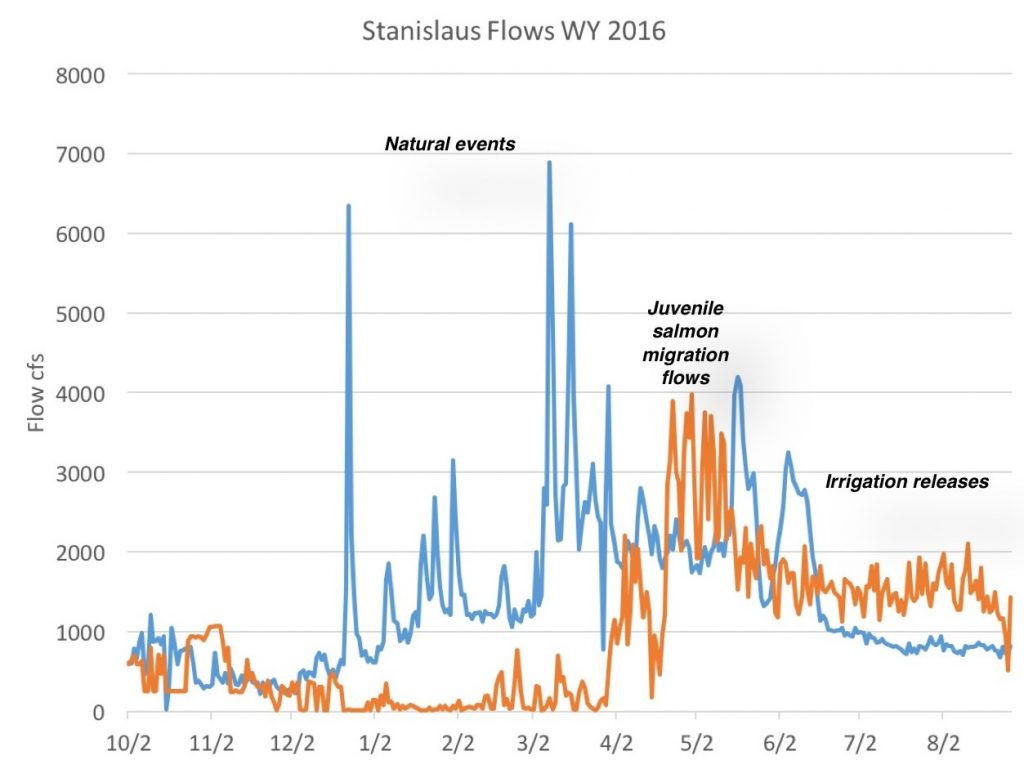

Much of the Valley’s snowmelt is captured in mountain and Valley rim reservoirs, breaking the link between the ocean and mountains. In the lower Sacramento River below Shasta Reservoir, spring snowmelt flows are markedly reduced by retention of snowmelt in the reservoir (Figure 1). The Feather River, the main Sacramento River tributary, are similarly affected (Figure 2). In the San Joaquin River watershed, absence of flows sourced in spring snowmelt is also severe (Figure 3). The capture of snowmelt not only reduces flow in Valley rivers and the Bay-Delta, but also reduces sediment load, river scour, water depths and velocities. It raises water temperatures and limits the extent of natural floodplain inundation. All of these are important ecological processes on which native fishes depend.

Figure 1. Pre-and post-Shasta flows in the lower Sacramento River near Red Bluff (Bend Bridge gage). Note that nearly all the peak spring snowmelt flows have been removed below Shasta in all year types. (USGS gage data)

Figure 3. Spring snowmelt (natural flow – blue line) is retained in New Melones Reservoir except for prescribed irrigation releases and salmon migration flows (orange line – reservoir releases to lower Stanislaus River). (CDEC data)

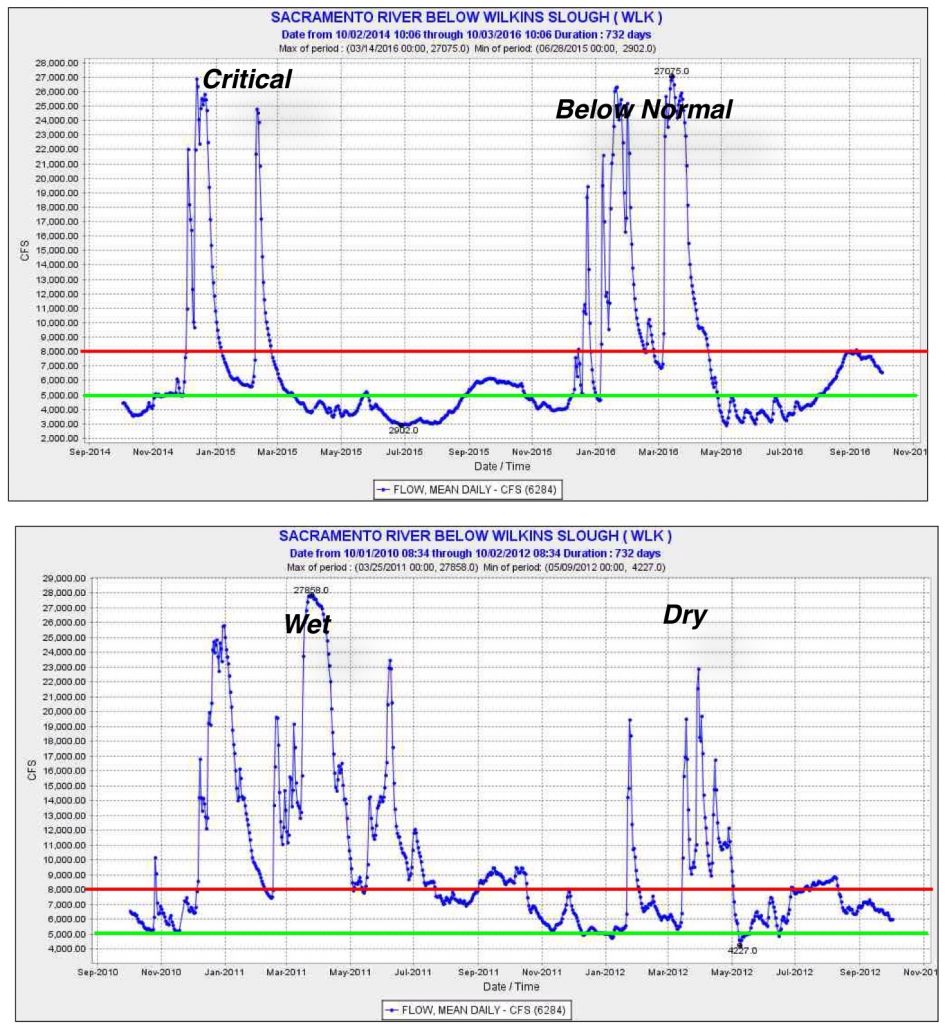

Under current operations, spring snowmelt into the Valley reservoirs is generally held in storage except for minimum downstream flow requirements, agricultural demands, Delta inflow and outflow to meet water quality standards, and minimum flow specifications for endangered fish in biological opinions. Flow releases for agriculture and fish are generally re-diverted soon after release, thus resulting in further reduction of downstream flows (this is the case for the lower Sacramento River in Figure 1, the lower Feather River in Figure 2, and lower Stanislaus River in Figure 3). Critical conditions often appear below these diversions in the lower Sacramento River (Figure 4), in the lower San Joaquin River, and in outflow from the Delta to the Bay.

What is needed are spring releases (spills) from the major Valley reservoirs to the major rivers below dams that carry at least in part to the Bay, to stimulate and sustain migrations of the adult and juvenile anadromous fish throughout the Valley. Water releases timed to the natural flow pulses would stimulate migration, providing even more flow and stimulus for young anadromous fish from all the Valley rivers to pass successfully through the Delta and Bay to the ocean.

Figure 4. River flow (cfs) in lower Sacramento River below major irrigation diversions in four recent years representing four water-year types. Green line represents minimum flow needed to maintain a semblance of essential ecological processes in the lower river. Red line represents preferred minimum level protecting ecological processes. May-June flow is generally depressed except in wet years.