Last week, the annual arrival of cedar waxwings hit my back yard near Sacramento. Each January, these magnificent birds fill my small back yard by the hundreds to feast for several days on the fermented fruit of three tall grape trees. The birds eat nearly every grape, likely a ton of fruit hanging from the branches. In several days the birds are gone, not to return for another year. I often wonder how important my little backyard piece of habitat is for this population of Cedar Waxwings, and how much of their winter energy comes from this small crop of fruit.

The birds remind me of another annual backyard run, the Cook Inlet Coho and Chinook salmon near Anchorage, Alaska, where I lived for three years in the mid-1980s. A large run of Coho showed up right on time each year at the end of summer in a creek that was literally in my back yard. Only kids were allowed to fish the city’s creeks for salmon, so I taught the neighborhood’s boys, including my 12-year-old son, how to catch and release the Coho. For a week or two, they could catch five or so bright ten-pounders in an hour or two a day. Me, I canoed down a tidal creek on the Kenai Peninsula side of the inlet and camp for a weekend to fish the fresh Coho run entering from the Inlet. I built a blind right on the creek within sight of the inlet. I could see the white backs of dozens of Beluga whales herding and feeding on the incoming salmon just a few dozen yards off the creek mouth. At night, the Coho approached the light of my Coleman lantern, even allowing a brief pet or two on my part, while maintaining steady and wary eye contact.

In the spring (late May), I often hitched a plane ride across the inlet (10 minutes and $40) to fish the spring Chinook run for a weekend of 24-hour daylight. At low tide, the small rivers were over 30-ft below the tule-lined channel. At high tide, the channel filled to the tules, along with seemingly bank-to-bank 30-lb spring-run salmon that obligingly hit any lure I put in front of them. This annual rush of spring Chinook lasted for a week or two before the fish moved upstream to await their late summer spawn.

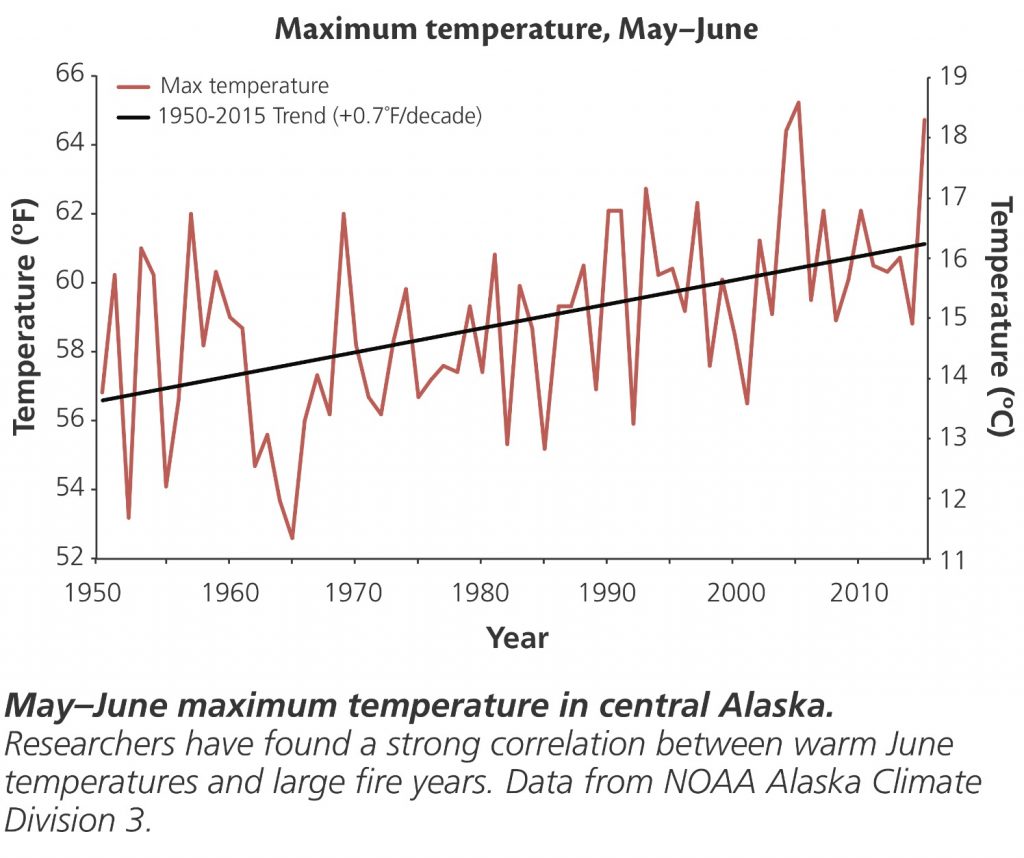

Today, thirty years later, things are not so good. After 30 years of increasingly intense subsistence, personal use,1 sport, and commercial fishing pressure, and most importantly severe ecological drought, the salmon runs have sharply declined. No doubt global warming has hit Alaska worse than other parts of North America, with high temperatures and low precipitation.2

Many of the streams are now closed to fishing. Where open, the annual bag limit of Chinook is only one fish per year. The Cook Inlet Beluga that once numbered in the thousands are down to several hundred and were listed as endangered in 2008. This decline occurred despite the fact that much of the habitat remains virtually pristine and untouched by man, with little influence of hatcheries. Global warming, overfishing, natural cycles, or ocean conditions: no one knows the cause for sure. Regardless, Alaska’s fish agencies must now manage its fisheries very conservatively with intensive adaptive management science. If you asked these agencies, they would say they had already been doing that for decades. They would also admit they learned a hard lesson. For more on their situation see:

http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=wildlifenews.view_article&articles_id=516 .

- Each state resident family could use a gillnet in the Inlet to catch 50 salmon per year for “personal use”. ↩

- https://nccwsc.usgs.gov/content/ecological-drought-alaska ↩