In a December 2018 post, I focused on the importance of fall pulse flows in moving winter-run salmon juveniles downstream in the Sacramento River to the Delta and Bay. Without pulse flows, the juvenile winter-run are less likely to make or survive the downstream move from spawning and early rearing areas in the upper river. They are thus less likely to reach the ocean and contribute to subsequent recruitment into the adult population.

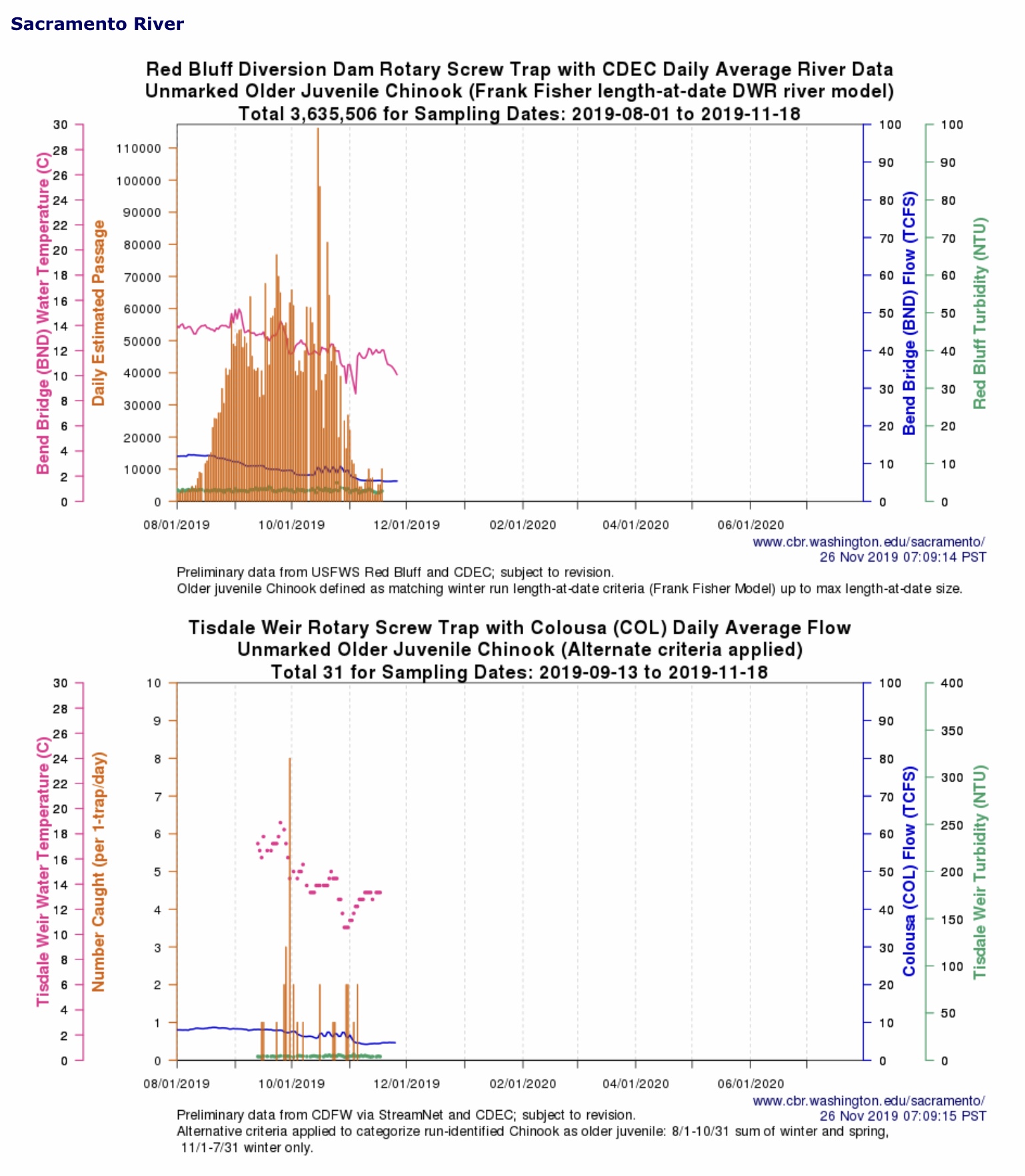

A gradual recovery of adult spawners, egg production, and wild fry production (Figure 1) has been helping recovery of the winter-run population since the population crash during the 2012-2015 drought. Wild fry production as estimated from Red Bluff screw trap collections is up sharply in 2019 (Figure 2 top chart).

However, in fall 2019, winter-run fry have received even less support in terms of river flow in their important journey to and through the Bay-Delta than in previous years. Numbers caught in lower river screw traps are very low (Figure 2 bottom chart), reflecting low movement rates from the upper river and poor survival. Both factors are a consequence of poor river flows. There are simply no reasons for Reclamation to be so stingy with Shasta Reservoir releases this fall, after a very wet year in 2019 and with Shasta Reservoir at or near a record-high level for this time of year.

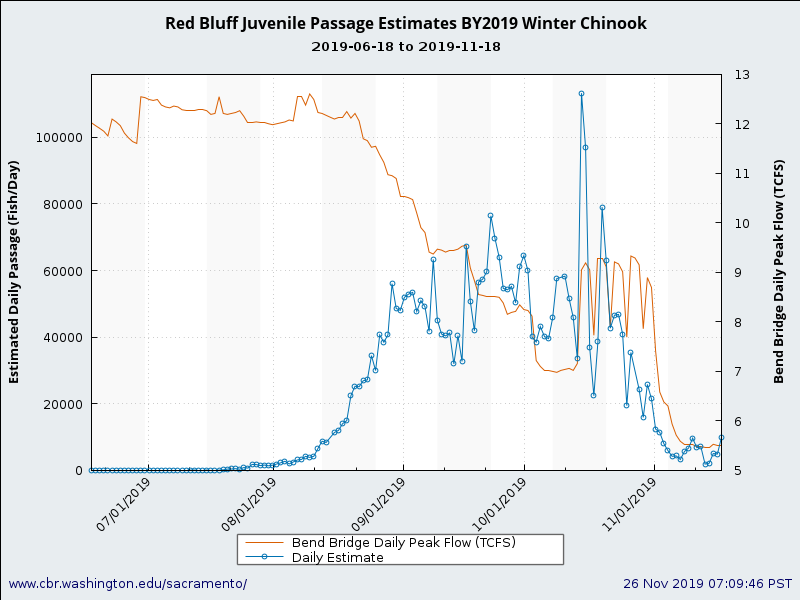

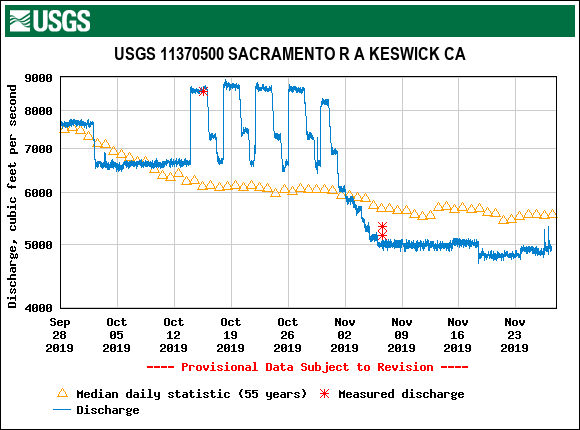

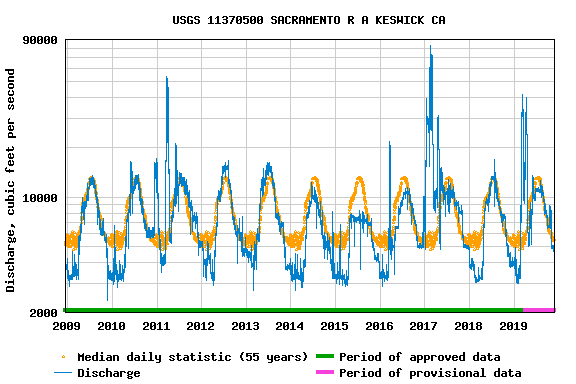

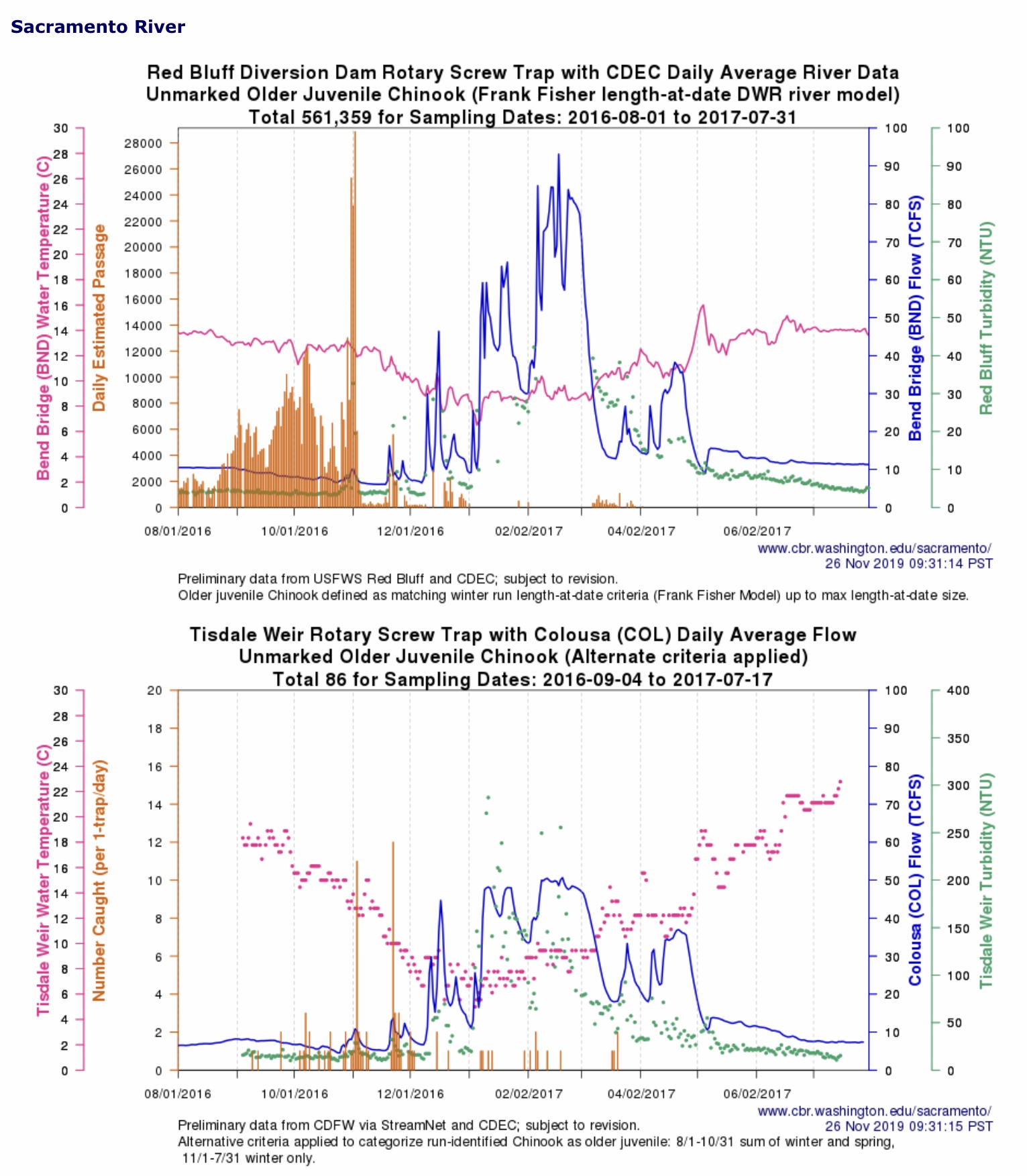

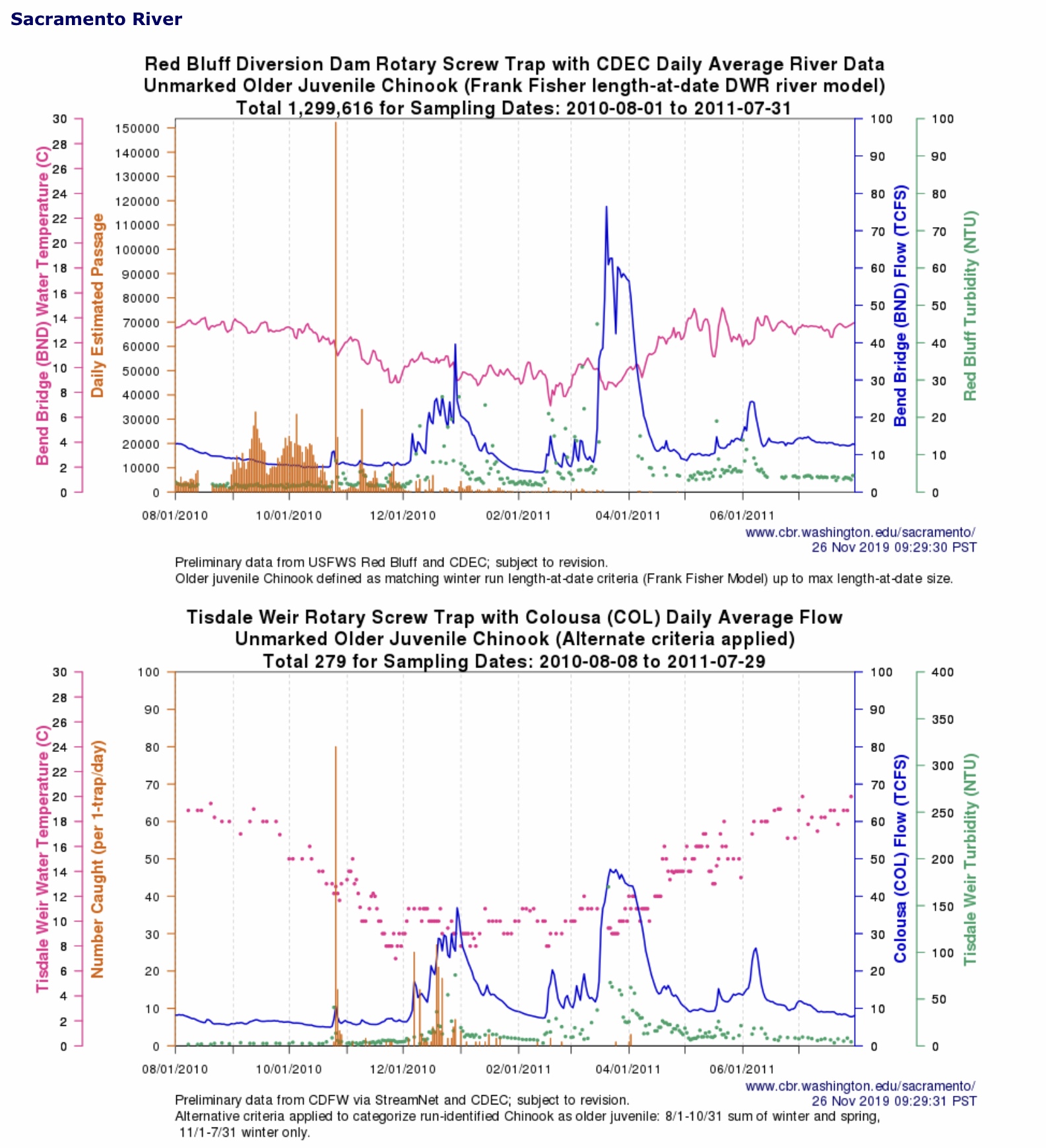

A close-up of the Figure 2 data in Figure 3 shows some effort on the part of Reclamation to provide flow pulses,1 but the effort was not enough. Furthermore, Reclamation subsequently offset its meager augmentation by cutting reservoir releases in November (Figure 4). The November reduction further compromised the emigration and survival of juvenile winter-run salmon. Reclamation’s tendency to cut releases in fall and winter, the period when winter-run most depend on river flows, is pronounced in all but the wettest years (2011 and 2017) over the past decade (Figure 5). Such tendency probably has been deemed acceptable because downstream tributary flows (Battle Creek, Cow Creek, etc.) provide fall flow pulses in some years (e.g., fall 2016 Figure 6, fall 2011 Figure 7). But inflow pulses from those tributaries are downstream of the Redding spawning reach; in the spawning reach, flows come almost exclusively from Shasta Reservoir releases.

What is needed are modest flow pulses from Shasta Reservoir in fall, especially when pulses in downstream tributaries occur. Releases for several days in the 10,000-15,000 cfs range, or of slightly less magnitude when coincident with tributary flow pulses, would help emigration (and survival) of winter-run juvenile salmon from the upper river. Such pulses should not be followed by offsetting flow decreases, as have occurred this fall (Figures 3 and 4). Low flows following fall pulses cause redd dewatering or fry stranding of spring-run, fall-run, and late-fall-run salmon, which spawn in the upper river later in the season than winter-run.

The late November 2019, Thanksgiving week storm should provide ample Shasta storage and tributary flows to allow modest flow pulses from Shasta Reservoir. Such flow pulses would benefit all four salmon runs in the Sacramento River.

Figure 1. Emigration timing of juvenile winter-run salmon from the upper Sacramento River and the estimated number of juvenile salmon (millions) passing Red Bluff during water years 2004-2018. Note the poor production in critically dry 2014 and 2015 from loss of cold-water pool and associated catastrophic egg mortality.

Figure 2. Daily estimated juvenile winter-run salmon catch per trap day passing Red Bluff in the upper river and Tisdale Weir in the lower river in summer-fall 2019. The numbers passing Red Bluff are strong, especially when one considers that they were the offspring of poor brood-year 2016.

Figure 3. Daily estimated juvenile winter-run salmon passage per trap day at Red Bluff in the upper river, also showing river flow in summer and fall 2019.

Figure 4. Shasta/Keswick Dam releases in fall 2019, along with daily median flow average for 55 years.

Figure 5. Shasta/Keswick Dam daily average releases from 2009-2019, along with daily median flow average for 55 years.

Figure 6. Daily estimated juvenile winter-run salmon passage per trap day passing Red Bluff in the upper river and Tisdale Weir in the lower river in fall 2016. Note that the flow pulses (and associated higher catches) in early and late November were from tributary storm-related inflows. Such events had not occurred as yet in 2019 (Figure2).

Figure 7. Daily estimated juvenile winter-run salmon passage per trap day passing Red Bluff in the upper river and Tisdale Weir in the lower river in fall 2010. Note the flow pulses (and associated higher catches) in late October and in December.

- Reclamation’s sporadic 2000 cfs flow pulses in late October observable in Figures 2 and 3 were likely part of Reclamation’s contribution to maintaining Delta inflow and outflow for the Fall X2 requirement. ↩