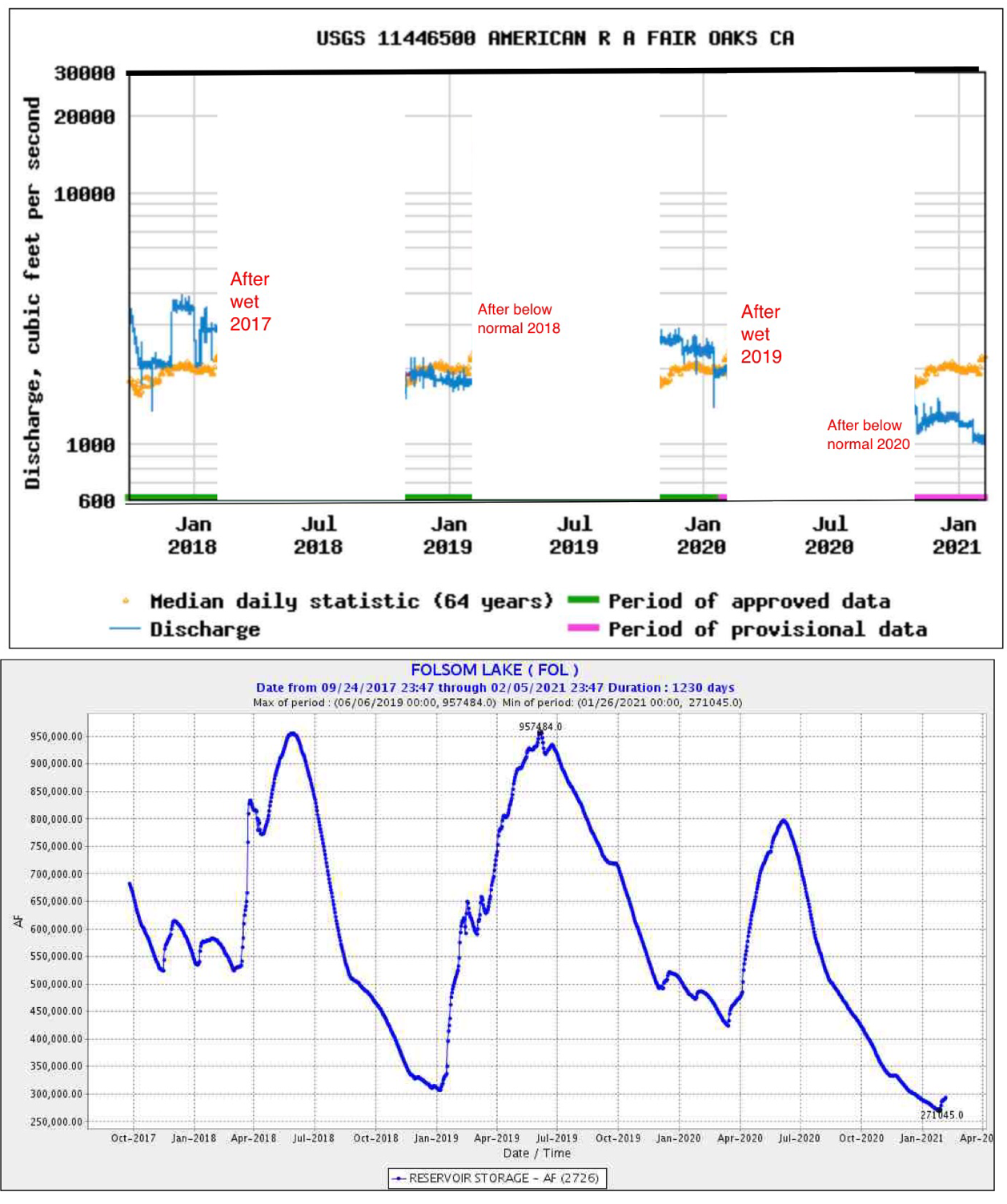

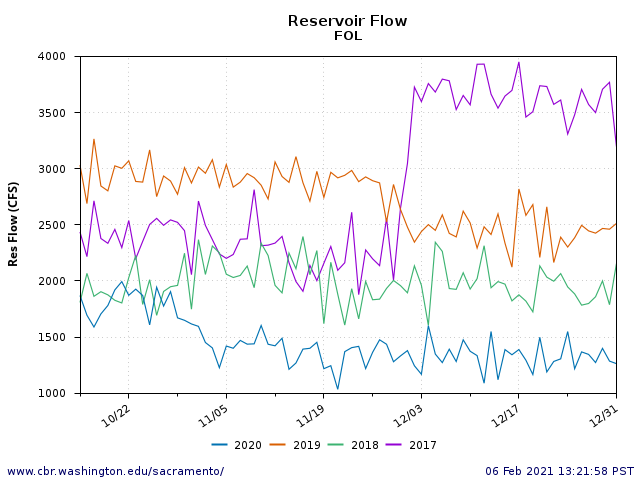

Water year 2021 has been bad for American River salmon and steelhead, with very low Folsom Reservoir releases Oct-Jan (Figure 1a). Water year 2021 can best be described as a dry year, at least through the first quarter, somewhat on the drier side of 2018 and 2020, which were below normal water years. However, whereas 2018 and 2020 followed wet years, water year 2021 follows a drier year. This means 2021 started with poorer Folsom Reservoir storage (Figure 1b).

Water year 2021’s low fall and early winter reservoir releases from Folsom were nearer to 1000 cfs than the normal 2000 cfs. As a result, much of the good spawning and early rearing fry habitat in the river below the dams remained dry (Figure 2). In contrast, even in drought year 2014, the side channel spawning habitat remained slightly watered at 600 cfs river flow (Figure 3). So, not only are redds dewatering in early winter of these dry years, the dewatering or drying of the side channels is getting worse. This is either because the main channel is incising from persistent scouring or because sediment deposition blocks the entrance to the side channels, leaving perched side channels high and dry.

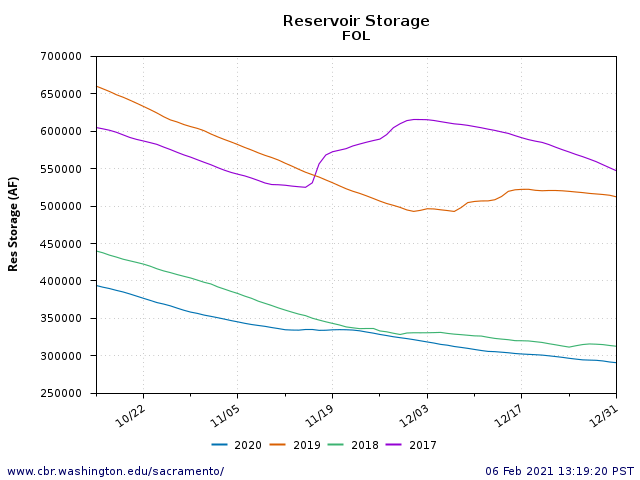

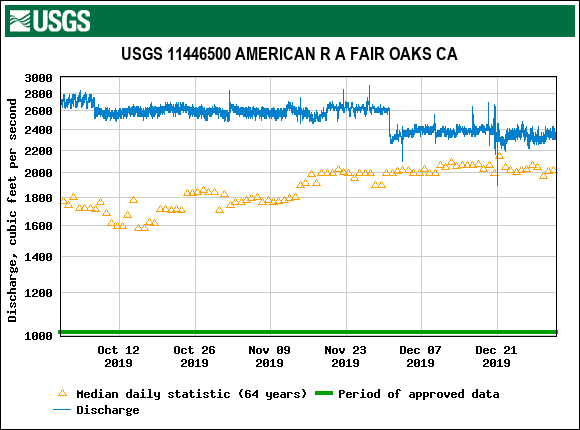

What got us into this predicament? Was it simply Mother Nature or global warming? Water management should take part of the blame (Figures 4 and 5). The end-of-September Folsom storage in 2019 was higher than average at 700 TAF after a wet year. Flood control rules required reservoir levels to be down to 600 TAF in November. But storage dropped to 500 TAF, with higher-than-normal fall releases (Figure 6), essentially shorting the reservoir 100 TAF in the new 2020 water year.

The American River Water Forum Agreement Is designed to manage and protect all water users, including salmon. Its formula for reservoir releases is based on natural flow input levels to the reservoir for that water year, which was lower than normal in 2020, thus leading to the prescribed low fall 2020 reservoir releases. With reduced storage and low reservoir inflow in 2020, it was impractical to release the needed 2000 cfs for salmon and steelhead in fall 2020 without dropping the reservoir down to 200 TAF in what could be a drought year.

In conclusion, the American River salmon and steelhead are at the mercy of a precarious water management system that can go from good to bad in one water year. One answer to this low fall flow problem is to ensure there is an extra 50-100 TAF of reservoir storage at the end of September to maintain the needed higher fall and winter flows for salmon and steelhead. Because the channel morphology also continues to change, sediment supply and river morphology must also be taken into account, if not also adjusted.

Figure 1. Oct-Jan Folsom Reservoir releases 2017-2021 with long term average (above) and reservoir storage (below).

Figure 2. Sunrise side channel (looking upstream) end of January 2021 with some of the best spawning and rearing habitat for salmon and steelhead in the lower American River nearly dry with river flows at 1000 cfs. Other important side and main channel spawning and rearing habitats were similarly compromised. Note main channel is at extreme left middle of photo.

Figure 3. Sunrise side channel (looking downstream) on January 15, 2014. Some of the best spawning and rearing habitat for salmon and steelhead in the lower American River is in this side channel. In 2014 as shown, it was almost dry with river flows at 600 cfs. Note tops of salmon redds sticking out of the water in various stages of dewatering. The redds were dug by salmon earlier in fall 2013 at 1200 cfs.

Figure 4. Folsom Reservoir storage (acre-ft) in fall 2017-2020. Water years 2017 and 2019 were wet years, and water years 2018 and 2020 were below normal years.

Figure 5. Folsom Reservoir releases (cfs) in fall 2017-2020. Water years 2017 and 2019 were wet years, and water years 2018 and 2020 were below normal years.

Figure 6. Folsom Reservoir release (cfs) in fall 2019 with 64-year average.