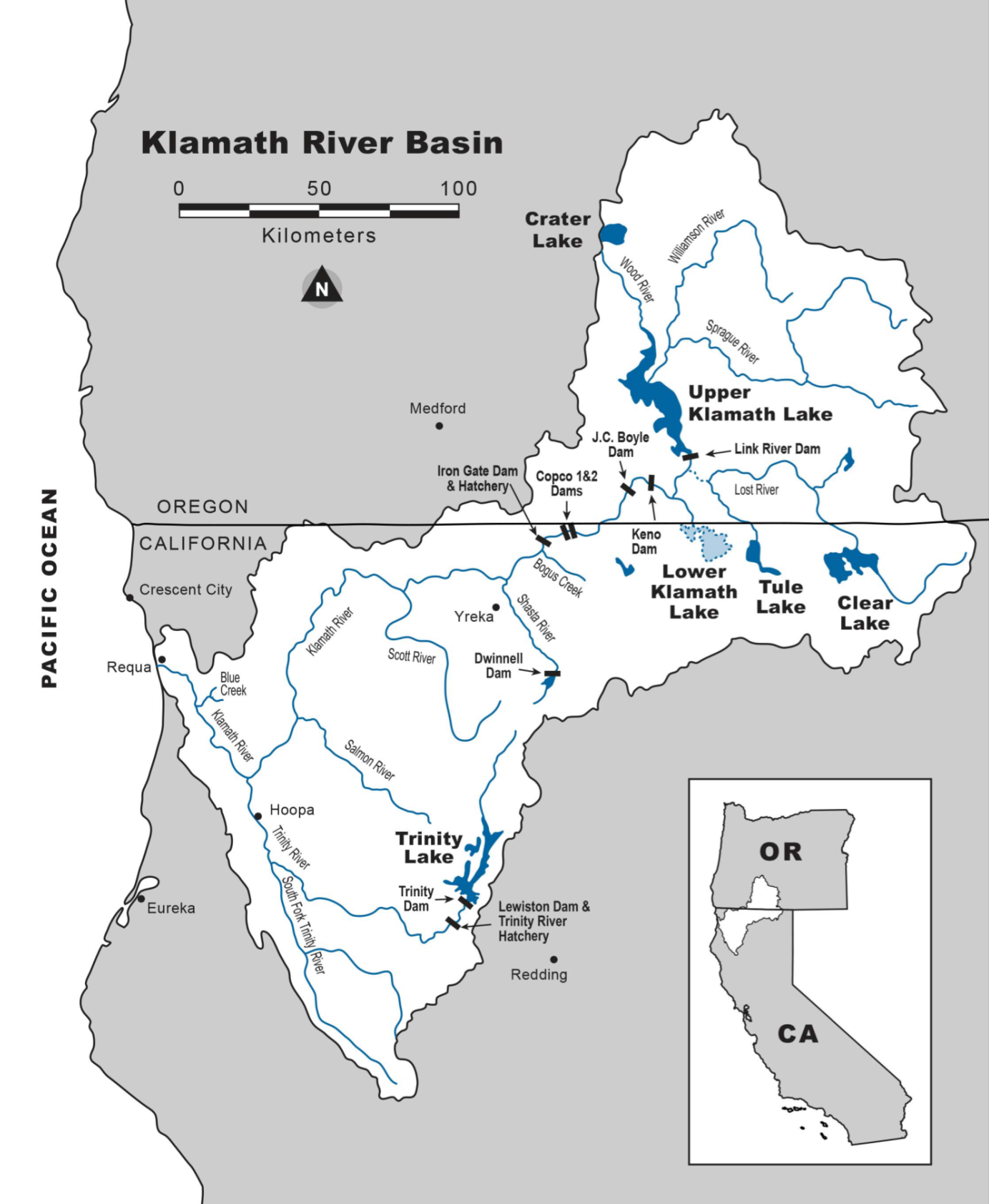

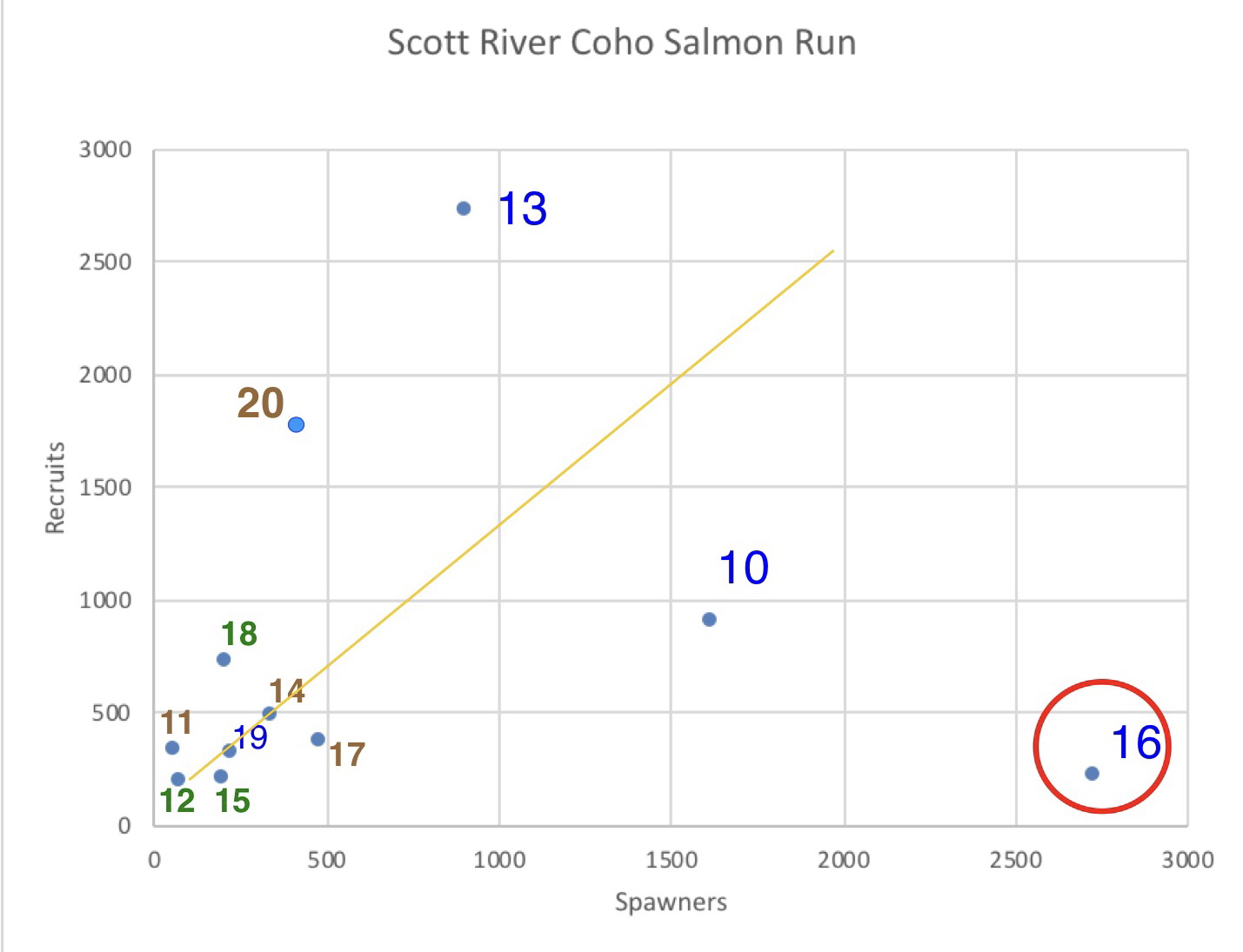

I last updated the status of Coho salmon in the Scott River, a major Klamath River tributary in northern California east of Yreka (Figures 1 and 2), in a January 2020 post. At that time, I lamented on the decline of the strongest distinct population subgroup, 2013-2016-2019, exemplified by the weak run in 2016 caused by the 2013-2016 drought. In this post, I am happy to report on the strong 2020 run and the surprise improvement of the 2014-2017-2020 subgroup (Figure 3).

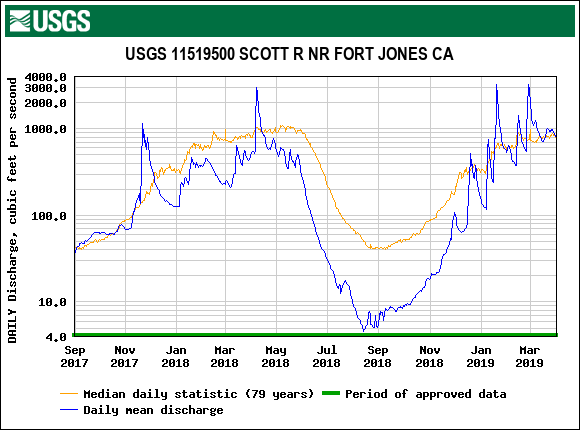

The improvement in the 2020 run, despite a sparse spawning run in late-fall 2017, is likely a consequence of good water conditions in early water year 2018 (Oct 2017-Sep 2018, Figure 4) after wet water year 2017. The run had good access to spawning habitat and early rearing conditions from fall 2017 through the spring of 2018. The young coho were sustained though the dry summer of 2018 in spring-fed reaches of the upper river and its tributaries. Spring-fed habitats likely benefitted from the abundant winter 2017 snowpack. The Scott watershed had also benefitted from significant restoration of its over-summering habitat over the past decade.1

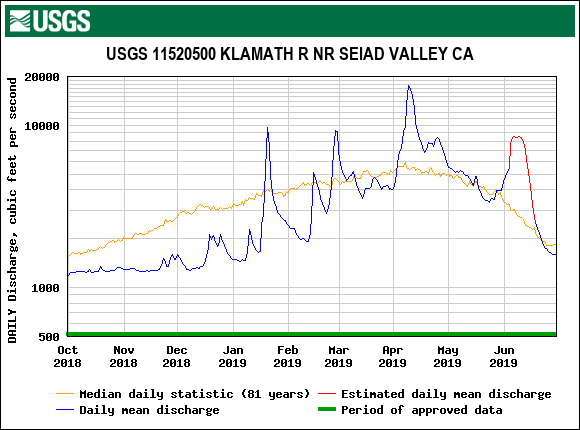

The yearlings of brood year 2017 then had good wet year emigrating conditions in late fall 2018 and early winter 2019 (Figures 4 and 5). There were multiple winter flow pulses to help the yearling coho smolts emigrate from Scott Valley and on down the Klamath to the ocean.

In summary, the spawning run in fall 2020 (from brood year 2017) was exceptional, benefitting from conditions that were a consequence of wet years 2017 and 2019. Over-summering survival in dry year 2018 was likely good because of good spring-fed flows and habitat in the upper watershed, a carryover from the good 2017 snowpack and restoration of beaver-pond habitat by Scott Valley stakeholder groups. This one small success bodes well for recovering other salmon and steelhead populations throughout the Klamath watershed, especially in a future dominated by climate change.2

Figure 1. Klamath River watershed with the Scott River west of Yreka, CA. (Source DOI.)

Figure 2. Google Earth view of the Scott River watershed with its snow-covered Marble Mtns to the west and the Trinity Alps to the south. Scott Valley, with its green hay fields from Etna to Fort Jones, was once called “beaver valley” due to its abundance of spring-fed beaver ponds and meadow streams ideal for over-summering salmon and steelhead.

Figure 3. Spawner-recruit relationship for Scott River Coho salmon. The number represents recruits (spawner counts) for that year versus spawners counts from three years earlier. For example: “13” represents spawner counts (recruits) in fall 2013 versus spawner numbers three years earlier in 2010. Number color represents different spawner subgroups (blue=subgroup 10-13-16-19). The Red circle highlights the significant outlier in 2016. The Yellow line is trend-line for years other than 2016 and 2020. Data source: CDFW weir counts.

Figure 4. Scott River streamflow measured downstream of Fort Jones as the river leaves Scott Valley, September 2017 to April 2019. Note the near average wet winters in 2018 and 2019, and dry summer in 2018 typical of the Mediterranean climate of northern California. The drier-than-average summer 2018 is indicative of water use for hay-pasture irrigation.

Figure 5. Klamath River streamflow measured downstream of the mouth of the Scott River, October 2018 to June 2019. Note the near average wet winter-spring with five distinct flow pulses typical of wetter years. of the Mediterranean climate of northern California. The flow pulses helped yearling coho from brood year 2017 emigrate to the ocean. The adults from brood year 2017 returned in late fall of 2020.